The following interview was conducted via email between April 23 and June 16, 2018, and has been edited for print.

CANDICE LIN: I wanted to start a conversation with you around a stupendous and controversial lecture you gave in September 2017, at the Walker Art Center, titled “The Most American Thing Ever Is in Fact American Indians.” It was refreshing to read the way you addressed the Jimmie Durham controversy in that talk, bringing in much of the complexity that was lost in some of the polarized fervor around the debate.1 But there were other bold and provocative statements that I really wanted to ask you to expand on.

The first question I had was about academic citation. In the lecture, you say:

There’s another new trend I absolutely hate, and I am baffled that people I deeply respect are on board. It’s called “politics of citation.” It seems to have started in Canada, not so long ago the home of the smartest and most talented Indian artists on the planet. This flavor of the politics of citation seems to involve making a declaration, perhaps in the manner of Chief Joseph, never again to cite a person in your writings who is not indigenous. This is—how should I put this?—unfathomably stupid. I expect this will soon be followed by indigenous art histories which refuse to acknowledge Picasso or Warhol or Basquiat, who after all are just settlers anyway. They have nothing to teach American Indians. Come on, people. This is crazy, building a dumb little prison and sealing yourself off in it. Stop it.

My familiarity with the “politics of citation” comes not from Canada, as you reference, but from a feminist context, where, for example, Sara Ahmed observes how the practice of citation acts as a “screening technique,” which is a way “of making certain bodies and thematics core to the discipline,” while others are continually excluded, even when those excluded have written and worked extensively on the topic at hand. Ahmed gives as an example a panel that she attended on the subject of reproductive justice. Feminists have extensively written about this subject, yet “two of the three papers were entirely framed around the work of male philosophers.” As a response, Ahmed asks writers and thinkers to put into practice a “citational rebellion,” and in her book Living a Feminist Life (2017), she lives this practice by refusing to cite any white men.2 Ahmed’s call to citational rebellion counters the dominant sources that are normatively cited more often, which are not neutral, and which privilege the voice and perspective of white and/or male authority. Perhaps it’s worth noting that the artists you cite as examples of how art history would be impoverished without their contributions are all men. Zoe Todd takes Ahmed’s call to citational rebellion from a feminist context and applies it to an indigenous one, which is perhaps closer to the academic circles you have encountered it in. In Todd’s essay, “An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on the Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word for Colonialism,” she notes how “Euro-Western academic discourses” use the climate as “a blank commons to be populated by very Euro-Western theories of resilience, the Anthropocene, [and] Actor Network Theory” without citing or perhaps even being aware of competing and overlapping discourses occurring in indigenous circles of thought.3

Your critique of this politics of citation seems to see this practice as ridden with the pitfalls of identity-based essentialism as well as an increasingly polarized political insularity that is indicative of our contemporary moment. The emotional frustration of your reaction resonated with me, but not the content of your critique. I read part of your rejection as stemming from a populist, anti-elitist perspective that I respect, sympathize with, and value in your writing, which so effectively uses humor to provoke and add complexity to reductionist and flattening narratives. But Ahmed does not ask us to refuse to read or be knowledgeable about a multiplicity of voices upon a subject or only to listen to voices like our own. In fact, she calls us to do the very opposite: the practice of citational rebellion asks us to hear all the voices in the room, not just the loudest ones. I’m sure you get that, and that is not what you are objecting to.

There seems to be a connection between your critique of a politics of citation and your exhibition (co-curated with Cécile R. Ganteaume), Americans, which opened at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian on January 18, 2018, and continues until 2022.4 The exhibition looks at popular imagery—such as branding, advertisements, and the names of sports teams, weapons, and automobiles—that represents “Indian-ness,” many would say in a racist and stereotypical way. One of your images accompanying your lecture on the Walker’s website is a definition of jiujitsu, a Japanese martial arts technique that utilizes the adversary’s own strength and weight against them, to one’s own benefit. Your use of mainstream representations of Indians permeating American culture seems to bear a strategic similarity to jiujitsu, and I wonder if it parallels your desire not to reject the dominant canon (of philosophers, writers, and artists) but rather to use seemingly familiar citation to reach an audience in a way that does not merely reinscribe the dominant story. Is your rejection of citational politics in academia a strategy? And if so, for what end?

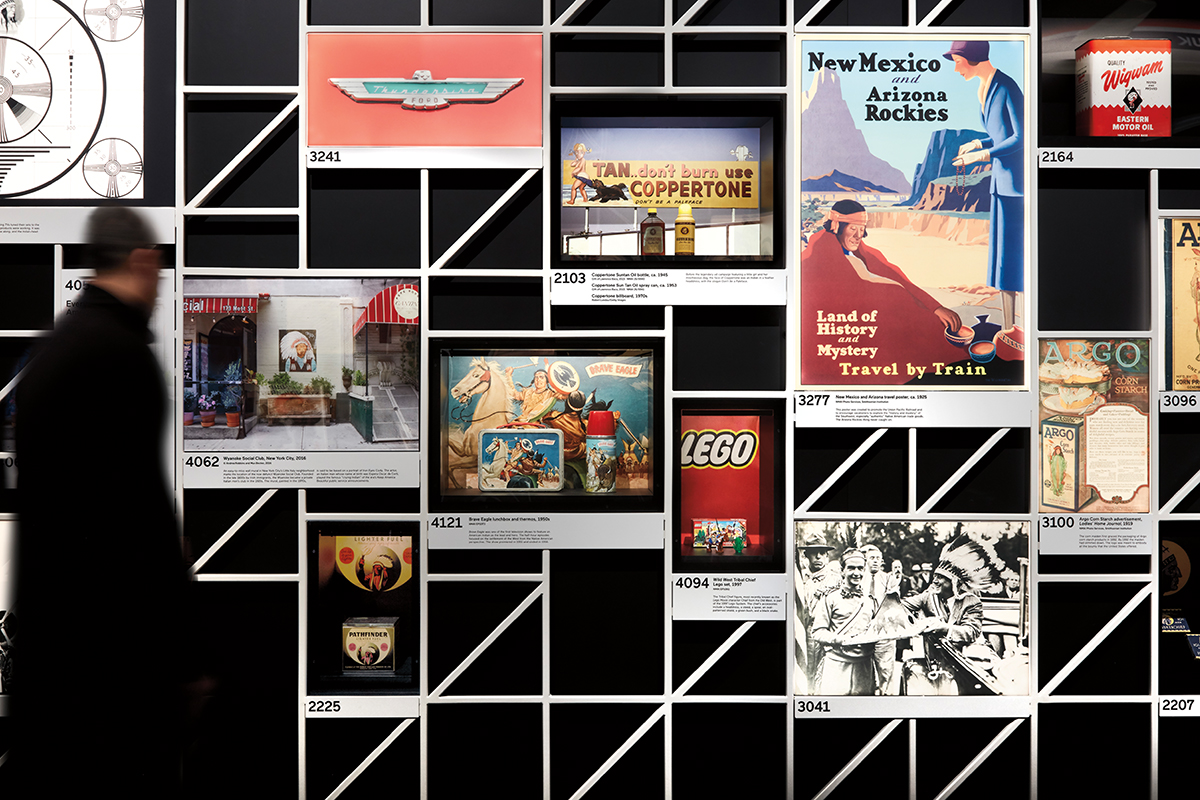

View of the central gallery that includes nearly 350 representations of American Indians in pop culture. Installation view, Americans, Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, January 18, 2018–22. Photo: Thomas Loof for the National Museum of the American Indian.

PAUL CHAAT SMITH: Back in the early 1970s, before we realized he was a monster, my crowd used to quote Mao: “No investigation, no right to speak.” I did not investigate the roots and deeper thinking behind the politics of citation, and I certainly take your notes about the complexities at work here and that many proponents do not argue for ignoring texts or willful ignorance. And I always understood knowledge is political and never neutral, and what is considered canonical (I don’t think I’ve ever used that word before!) has tremendous impact on future scholarship. I get all that. My (mostly self taught) training is to look at everything, and look at everything critically. I don’t think it is that complicated, really. I agree there (probably) can be an intelligent version of the politics of citation.

I also think there’s validity to critiquing the phenomenon as I have experienced it, which is different from the feminist context of Ahmed’s work that you reference. From my corner of the broader discourse of Native Studies, politics of citation is one of the trophies from what I call the War Against Essentialism. (Spoiler alert: essentialism won.) It really is as blatant as saying nothing should be cited except the indigenous, and it is frightening and willfully stupid. It is such a dumb argument that it is difficult to argue with it.

I have no doubt people way smarter than I am are fighting in the trenches of academia to improve their fields, which I presume are still heavily weighted in certain directions. Although I’m not sure of that. I know it might sound like I’m falling for all the anti-intellectual perspective that the whole world is Evergreen State College propaganda. But, really, this is based on my experience with colleagues and students. And lots of them, including you, have spoken of a sense of fear and anxiety about saying the wrong thing. I’d love to meet some of the smart advocates of politics of citation, and I’m sure they are out there. So far, I’ve only met the zealots.

LIN: In an earlier conversation that we had when you were visiting Los Angeles, you brought up your excitement for the Afro-pessimist critique of settler-colonial discourse. This is the second point of your Walker talk that I want to ask you to elaborate more on. In your Walker lecture you say:

I’m curious about a new trend among my colleagues in indigenous studies. They are fond of using the term “settlers” to refer to basically everyone they see on a daily basis who’s not Indian. When I first heard it, I thought it was a joke. I’ve been thinking a lot about a statement by a Mohawk artist named Skawennati. She was wondering why so few Native artists ever make work about their white relatives and family members and significant others. I suppose those artists whose extended families are pure red all the way down are off the hook, but not really, because they probably don’t exist, and also because Skawennati’s critique is about curiosity and range. But what she’s talking about are the Native people she knows. They’re not bitter from bad experiences with these white people. . . . They’re family, they’re their spouses, and yet somehow, somewhere, somebody might make some art that involves them, and it’s curious that seems to never show up.5

This statement by Skawennati also seems related to another topic you’ve been writing and thinking about, especially in “Notes on a Future Reckoning,” which is Indian and Black relations in the 1960s and 1970s and tracing that back to the history of Indigenous participation in African enslavement:

I miss the Seventies. Remember, back when Afrocentrism was in full bloom, and black kids were being taught about the Ice People and the Fire People and how the Egyptians invented the airplane? Well, we had a similar jam going, and in those days here’s what we said about Indians being slaveowners. First, that’s all a lie. Second, later, we admitted there was some of that going on, but actually those weren’t Cherokees or Choctaws, they were white people who said they were Cherokee or Choctaw. And, I remember hearing another iteration that said sometimes we’d pretend we owned slaves, just to protect our brothers and sisters from the slave-catchers. In later decades, it was admitted that okay, some Cherokee and Choctaw and Seminole and Creeks did own slaves. However, that it wasn’t really the same as when white people owned slaves. It was a kinder, gentler type of thing. And it wasn’t that many who did this bad thing. (Note: most white Mississippians didn’t own slaves either.) That’s what we still were saying into the current century. My favorite version, which this Museum [the National Museum of the American Indian] and many others have relayed, is what I call the Samsonite Narrative. And this story focuses on the Trail of Tears as the place to admit there was slavery going on, and in careful, studied, neutral, and boring sentences—think the iTunes End User Agreement—describes how some of the tearful exiled Indians owned slaves and brought them along with other possessions on the death march to Indian Territory. Interesting! But not really! Pay no attention, nothing to see here.

For the Americans exhibition, which opened in January in Washington, the Samsonite Narrative was not an option, because our thesis was that the Removal Act (which led to the Trail of Tears) eliminated the last obstacle to the brutal blossoming of the Cotton Kingdom. It would have been dishonest to talk about Removal’s relationship to the explosion in slavery and downplay the fact that some Indian nations enthusiastically embraced it.6

I see your comments together as part of a larger project to complicate the question of race (perhaps in your own war against essentialism) by teasing out assumptions, for example, that all Native people have progressive politics, or that Black and indigenous relations have always been collaborative and in solidarity. Which brings us to the question of settlers and colonists and what you identify as a current trend of calling all non-Indian peoples “settlers.”

Detail from the central gallery. Installation view, Americans, Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Photo: Thomas Loof for the National Museum of the American Indian.

I agree with you that some of the strongest and best arguments against this move have come from academics, some of them Afro-pessimists in Black studies, as you brought up. I recently read an essay by Nandita Sharma called “Strategic Anti-Essentialism: Decolonizing Decolonization,” in the Sylvia Wynter anthology that addressed this very subject.7 Sharma asks, “In our present ‘great age’ of migration, how did ‘colonizer’ become a meaningful way to describe people who move across space? Indeed, how did ‘colonizer’ come to be an increasingly dominant mode of representing indigenous people’s others, others who were once understood as co-colonized people, or at least, not as an oppositional other? Is there a relationship between these particularistic modes of representation and the false separation and hierarchical ranking of different but related experiences of colonization, such as the processes of expropriation and people’s displacement across space?”8 I think that Sharma’s argument is about the complexity that is lost in a binary position that pivots around dispossession of land, without a consideration of other kinds of dispossession or oppression.

I wonder what you think might be gained in rejecting and countering an essentialist politic? If the gains of the 1990s identity-politics movement in contemporary art were the representation of more artists of color and a broader spectrum of subjectivities, the critique is often that it was reductive and essentialist. How do you take a strategically anti-essentialist position without losing these important political gains to visual representation?

SMITH: I’ve always been attracted to complexity, imperfection, failure, and the certainty I’m wrong about so very many things. At the same time, as a writer and thinker I strive for coherence and, well, not simplicity but being understood by the widest range of people. And a measure of believing I’m not wrong, or at least not as wrong as other people. In other words, my core beliefs are at odds: understanding how complex and flawed everything is, and wanting that not to be the case.

Your example of the historical gains of an essentialist position is a good one. Affirmative action and identity politics are clumsy, stupid, and have limited effectiveness, along with a raft of unintended consequences. They are bad solutions to serious problems, and they may also be the least bad solutions we can devise. They are profoundly essentializing. When a white cultural institution hires a person of color, that person of color had better be really competent and is somehow standing in for all people of color. It is a setup, yet does that mean the white cultural institution shouldn’t hire people of color? (Also, why can’t we find a better name than people of color? Back in the 1980s, the term third world people was in vogue, even by Ford Foundation types. Didn’t last. I guess the third world people didn’t like it. Never cared for it myself. Maybe we should try colored people.)

Recently I came across this text I wrote for a Smithsonian exhibition in the early 2000s: “Just as they did in 1491, Native Americans today live in a land that is ancient and modern, diverse and always changing. They number in the tens of millions and live in the hemisphere’s most remote places and its biggest cities. They fly spacecraft and herd llamas, write software and grow orchids, fight wars and teach chemistry. They trade stocks from Park Avenue apartments, drive taxis through Lima’s rush hour, and sell shoes in Kentucky strip malls. Modern American Indians are not shadows of their ancestors, but their equals.” I was embarrassed by it; I was also kind of proud too. I liked the sentences and the beats, and I liked the saccharine tone and the deeply flawed notion these random things unite Indian people in a vague, unspecified way. Strategic essentialism is seductive. We go way back, and we’ve had some great times together.

Plains Indian objects on display in the Battle of Little Bighorn gallery. Installation view, Americans, Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Photo: Thomas Loof for the National Museum of the American Indian.

You asked what is to be gained in countering an essentialist politics. Not much, probably. We are in a period so different than, say, post-WWII, or the 1960s and 1970s, when political transformations, even revolution, seemed possible, if not imminent. That idea that if we only found the right brand of Marxism, injected with feminist theory and anti-racism, we’d be on our way. I don’t know anyone who thinks that now. The strategic essentialist version of Indian history is that once we had everything, and then the white eyes showed up, and they took it all. Except not everything, because we survived despite great odds. And we are still here, even though we lost everything.

Your next question was, How do you wage a strategic, anti-essentialist position without losing these important political gains to visual representation? I’ve been ruminating on writing a critique that argues the current Indian discourse is engineered by white supremacist thinking. As I investigated Southern Plains and Comanche history, I learned that what has come to be known as the Comanche Empire was a system built on rape, murder, and enslavement. You know, human behavior. What became interesting to me is that there is really no dispute that most of the raped, murdered, and enslaved were Indians or Mexicans. True, Comanches famously killed more white settlers than any other Indian tribe, but those numbers paled (sorry!) compared to the numbers of Mexicans and Indians. And it also became apparent that Comanches in their prime barely thought about the United States until late in the game. They didn’t give a rat’s ass about it, or white people, or the notion of race, or settler colonialism. In the strategic essentialist version, Comanches, like all other Indians, fought only to defend their homelands against the white eyes. Yes, maybe there was some intramural conflict, but that was no big deal really.

So, I’m thinking, as I read that one great regret of the Comanche Empire is the failure to completely exterminate the Apache (though we came close), why is it that every narrative is about Comanches and white Texans? Clearly, those narratives blatantly say that Comanche actions are only important as they impact white Americans. And you see this through every famous and not so famous Indian episode: that Indian nations were often aligned with Europeans against other Indians, for smart and foolish reasons. That narrative never gets traction, because, like the story of how Indians nearly wiped out the beaver population in the East because it was so profitable, it doesn’t fit. All Indians are on the same side, and all are virtuous.

I could go on and on, example after example. People get excited and nervous when I do, because even if these things are true, the bigger truth is that Indians were screwed by white people, and that is the most urgent issue. So, screw what the Cherokee did when they captured other Indians for the early slave trade, and later enslaved Africans, screw what the Comanche did to the Apache, those lives aren’t as important as white American lives.

The reason I decided not to write that essay is because it would perpetuate one of our main problems, which is the weight we give to terms like colonialism and white supremacy and the way we use them as shorthand to describe really complex situations. It’s playing the race card to discredit playing the race card.

I did end up in a modest but satisfying place: I’ve decided that a core principle moving forward is that Indians are fully human. It sounds silly and childish. I think it is anything but. To believe Indians are fully human requires believing Indians are capable of all the evil and good actions humans everywhere have carried out for the past hundred thousand years. I think Indians have been rendered less than fully human in the service of narratives designed to alleviate white guilt. When the narratives have been flattering, Indians have gone along.

The Trail of Tears gallery. Installation view, Americans, Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Photo: Thomas Loof for the National Museum of the American Indian.

Americans, the show I curated with Cécile R. Ganteaume, gently confronts visitors with hundreds of images and objects, from two centuries of American life, of Indians as abstractions. They too are mostly flattering; only a small number could be called vicious and demeaning. We are the country’s favorite minority group. There are worse things to be! However, maybe not as many as one would think. Can this approach lead to something useful? We’ll see.

I’m pleased about this critique of settler colonialism from the African American discourse. In a way, the settler-colonialist frame feels like the last gasp attempt to reclaim those glory days when we mattered more than other minority groups. I always wish people (Indians and others) could simply drop in for an afternoon on a random selection of venues where they could see Indians being Indians. Most of them are living lives very much like most Americans. Know why? Because most Indians are not very different from most other Americans. They drive settler cars, have settler jobs, often have settler spouses, watch settler television, and also are American citizens. Now, if one wants to say this argument only applies to “real Indians,” the dark skinned ones on Western reservations who are actively engaged in fighting settler colonialism, that would be an argument. It would also apply to a vanishingly small percentage of American Indians.

Settler colonialism? I think it’s a dead end, honestly.

What I want is a clear-eyed sense of the world. For me to keep believing in the strategic essentialist framing of the Red Nation means ignoring so much of what actually happens with Indians these days. How corrupt so many tribal governments are, how actively Right wing so many Indians in the United States are, the poverty, child abuse, and the rest.

I used to say that once this was all Indian land. I said it a lot. I believed it too. It has a kind of poetic truth, and even if it isn’t technically true, it is mostly true, or at least should be true. Except it isn’t. One can say the United States is a national project built on the dispossession of Native people. One can say most of the land that is now the United States was thoroughly known and explored by Indians before Europeans arrived. But you can’t really say it belonged to Indians. Some did, some didn’t. It’s a really big country, and even today there are places no human has ever set foot. Some Indian nations had formal rules about land use, others didn’t. Nobody has lived in the same place since the beginning of time.

The acknowledgement statements that have taken off in Canada and Australia and are getting popular here in the United States are interesting. “We are meeting on the unceded territory of the xxxx people.” In many cases, that is true and important. In many others, it isn’t true, or is so murky you’d need half an hour to explain our best understanding of whose land it might have been. In other cases, like the Sioux and many more, their land used to “belong” to other Indians before the Sioux ran them off.

I think most people are not wired to deal with nuance. If I talk about the Choctaw enslaving Africans, my agenda must be that I have something against the Choctaw, or that the goal is to make the horrors of Removal less important by distracting from the agreed upon main point, which is America bad, Indians good. Or that to raise those questions is an effort to say one negates the other. I get that. So maybe this discussion isn’t for most people, maybe it’s for people who can handle nuance, who believe humans are messy and weird and always more than one thing. Not for everybody, but so what?

Paul Chaat Smith is a Comanche author, essayist, and curator. His exhibitions include James Luna’s Emendatio; Fritz Scholder: Indian/Not Indian; Brian Jungen: Strange Comfort; and Americans. He has published two books: Everything You Know about Indians Is Wrong and Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee. When he isn’t crafting game-changing exhibitions and texts, he enjoys reading obsessively about the early days of the Soviet space program, watching massive amounts of sports, and writing about himself in the third person.

Candice Lin is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at Portikus, Frankfurt; Bétonsalon, Paris; and Gasworks, London.