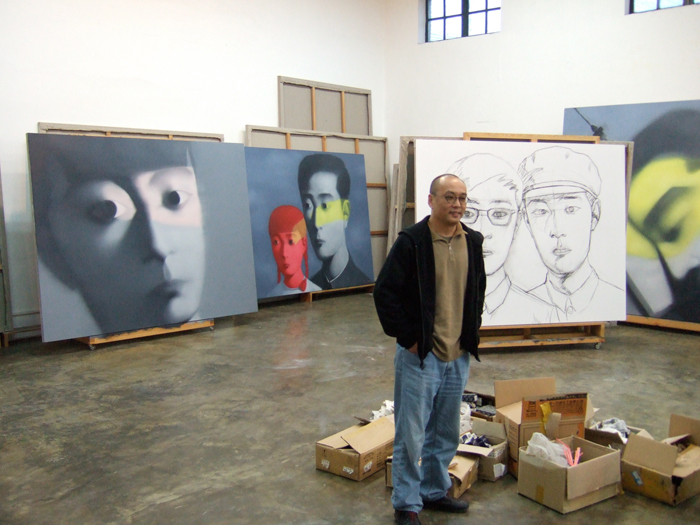

Zhang Xiagang in his studio, Beijing, Autumn 2006. Photo courtesy of Chinese Contemporary Gallery.

Audience

With viewers stacked three-deep at blockbuster museum exhibitions, communications and education departments no longer need to focus on seducing the public. For now, those that are going to come already do; those that aren’t convinced, won’t. But while visitors peer over heads attached to Acoustiguides, contemporary art galleries suffer (by comparison) from a lack of visitors. How can the art world—in particular, museums and the press—foster a more equitable distribution of these visitors, alleviating congestion and, by encouraging the public to sample a broader range of artworks, promote visual literacy? How can we make looking at emerging art accessible to as wide a range of people as possible?

Blogs

Why have blogs made so few inroads in the consciousness of the contemporary art world? The conversation surrounding music, literature and politics is now linked inextricably with online commentary, yet the same cannot be said of that surrounding art, despite the presence of smartly written, regularly updated sites. Is it because the personality type needed to maintain a blog is so specific, and, unlike music, literature and politics (topics that are not as dependent upon geography for specialized knowledge), art requires viewers to be in its presence, thus hindering the art blogger in Wichita, KS?

Conversation

Of the six major articles included in the hundredth issue of Frieze magazine, published last summer, only one—a history of art magazines—was written. The rest were interviews (with Tom Wolfe, Pierre Huyghe, and Yvonne Rainer), a survey (of influential writing), and a discussion (about criteria for judgment). The imbalance is indicative of a wider trend in trade magazines and exhibition catalogues: Conversation is ascendant. Panels likewise increasingly substitute for lectures. We are talking to hear ourselves talk, to blot out the silence of thought, and, perhaps, learning less in the process.

Dawkins’s law of the conservation of difficulty

Evolutionary biologist and popular science writer Richard Dawkins’s Law of the Conservation of Difficulty states that “obscurantism in an academic subject expands to fill the vacuum of its intrinsic simplicity.” He was writing about physics, but perhaps art historians and art critics can be accused of too often following the letter of his law.

Enthusiasm

Re-reading Paris Review interviews with Susan Sontag and George Steiner, I was struck by the fact that, late in their careers, both reserved their intellectual acumen for laudatory memorials and promotional prefaces, eschewing “negative” criticism. Yet the constructively critical review is, in my position, inevitable. With only so many opportunities to write, and without complete freedom to determine the subject of study, how can honest responses not admit ambivalence or worse? Pure, unbridled enthusiasm is apparently the province of privileged seniority: the privilege to ignore all that is mediocre.

Fairs

Here are two ideas for those who dislike art fairs. First, construct a calendar that takes you to the wrong place at the wrong time. Visit London in spring, Miami in summer, New York in autumn, and Basel in winter, and enjoy the art scene in each city unsullied by convention-center commercialism. Alternately, visit each city the weekend after the hoopla, viewing all of the museum and gallery exhibitions that opened to coincide with the fair, then return home with witty, up-to-date dinner-party repartee that will make it seem as if you’d suffered long days on the aisles.

Gallery catalogues

Given that catalogue reproductions cannot accurately convey the experience of spending time with a work of art, and electronic images are now of a high enough quality to compete with printed counterparts, why do commercial galleries scramble to produce thin volumes documenting relatively unremarkable exhibitions? Without the inclusion of an essay, interview, or other contextualizing material, what function does such a book serve? Often, they gather dust in storerooms until handed out for free to a collector who shows interest in the artist, after which they gather dust in a private library. Every catalogue designer makes a PDF to send to the printer. Why send it to the printer?

Hitting the streets

Continuous exposure to new art, with an ear attuned to the machinations of how that art came to be presented, can substitute for a master’s degree in curatorial studies; that same advanced degree cannot, however, substitute for pounding the pavement, week in and week out. It is perhaps easier, probably more rewarding, and certainly more risky to learn by doing, in public, than to develop in the chrysalis of the academy. If you have $25,000 (current annual tuition for one curatorial studies program), why not use it to offset living costs as you make your way toward a position that will support you and be fulfilling?

Inauthenticity

“The very reason I write is so that I might not sleepwalk through my entire life. But it is easy to admit that a sentence makes you wince; less easy to confront the fact that for many writers there will be paragraphs, whole characters, whole books through which one sleepwalks and for which ‘inauthentic’ is truly the correct term.” So writes Zadie Smith about fiction. Yet all of us who write are guilty of this. Critics who admonish artists for inattention to form too often neglect the composition of their words, undermining the rhetorical force of their arguments.

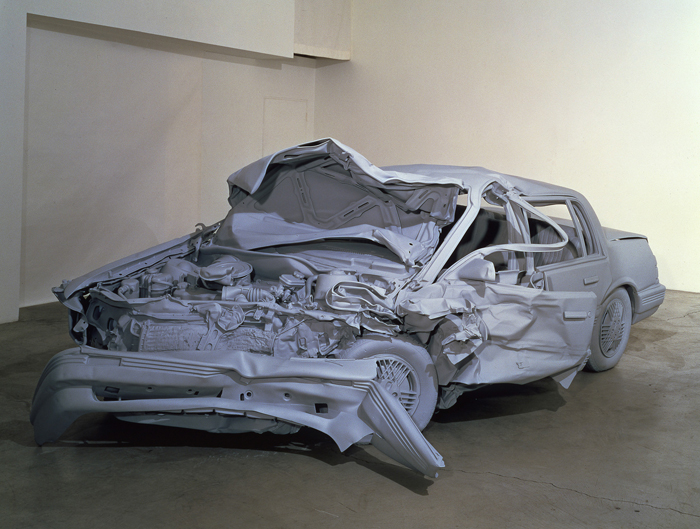

Charles Ray, Unpainted Sculpture, 1997. Fiberglass, paint; 60”H x 78”W x 171”L. Courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Journals

Artists, writers, dealers, curators: Write! Keep journals. Archive your thoughts, however roughly, and riffle through them occasionally, seeing what’s there to tweak or take up anew. Write down the stories you hear at the opening reception or the bar. The material provides a record invaluable as an index of your own growth—a reminder that what seems stagnant is not—and, later, as a chronicle offering insights to those who weren’t around to exult in the highs and mourn the lows. Every time and place is unique, and made more so by the singular consciousness through which it is filtered; making sense of it on paper is a dying art form that I hope can be revived.

Kaizen

The Japanese term kaizen, which translates as “continuous improvement,” is an approach to corporate productivity that stresses the elimination of waste, just-in- time delivery, and the use of appropriate equipment. Its adherents want to take something apart and put it back together in a better way. How can the art world appropriate this ethos? Some have begun to do so literally: Dexter/Sinister, a “just-in- time workshop and occasional bookstore” headed by two graphic designers in New York, applies Fordist and Toyotaist production models to the creation of printed objects—art catalogues and the like. Can it be applied to ideas, concepts, artworks, dialogue? Can kaizen blend with the agora?

Location

“Polyphony of centers” is a catchphrase that some international curators use to refer to the fact that significant cultural production occurs in an ever-greater number of locations. But the phrase (and the utopian sentiment underpinning it) neglects very real imbalances: Some are more central than others. Who among MFA graduates at Cranbrook will opt to stay in Detroit, when New York issues its siren call? Only after a critical mass of artists, dealers, curators, writers, and other producers commit to a city for years can it be conceived as a “center.” How can we encourage this? (I ask having left Boston for New York.) Until this commitment takes root, extracting artists from less populous locations and placing them in international contexts often (paradoxically) undermines the solidity of the community from which they’re drawn, perpetuating center-periphery inequalities, precisely the condition supposedly remedied by the creation of a “polyphony of centers.”

Mirra, Helen

When writing about art, there are certain artists whose work you feel compelled not only to follow, but also to comment on repeatedly. Helen Mirra, once based in Chicago and now in Cambridge, MA, is the Johnson to my Boswell (though I hesitate to suggest I could produce a portrait as strong as Boswell’s). Her subtly shifting practice, with its steady engagement with late-nineteenth-century philosophy and late- modernist form, is for me a world complete unto itself, something steady enough that I can calibrate my own positions, my changing attitudes, against it.

New world

“It’s a new world,” said Tobias Meyer, Sotheby’s New York–based contemporary art chief, recently. “The new buyers don’t care about price.” Should critics? What percentage of critics’ energy should be devoted to studying and commenting upon the world (and the money) that surrounds art objects? How often should writers seek space on the Op-Ed page in order to defend or decry certain art-world practices? Does this new world need cartographers limning its borders?

One-room exhibitions

From the fifth-floor group shows organized by David Kiehl at the Whitney to Manet and the Execution of Maximilian at MoMA to Cimabue at the Frick (limit: twelve viewers at a time), some of the best exhibitions recently presented in New York have offered tightly constructed narratives that need only one room to make their point. Presenting smaller exhibitions, and turning them over more quickly, allows an institution to be nimbler and more responsive to ideas in the air at a given moment. Basing them on permanent collections affords curators time to rethink what’s at hand, to divine unexpected juxtapositions.

Power

Power, in the minds of most in the art world, is an abstract thing. What remains undefined in declarative lists such as Art Review’s annual Power 100 is who nominates? Over whom is the power held? How is it exercised? These factors are as important as what is chronicled, which is primarily money. Most people consider power something one can possess, like money. What is often forgotten is that influence, like affluence, can lead to a pathological disconnect not only from one’s surroundings, but also from one’s own needs, abilities, and—perhaps most importantly—limits. In acknowledging that resources and opportunities (and the power they generate) are finite, one almost immediately enters a hoarding mindset. How can we discourage the wanton expansion of “power footprints,” and encourage an acknowledgement of limitations?

Questions without answers

Johanna Burton, in an interview in Texte zur Kunst: “When you’re outside, you think you see things really clearly, and once you’ve been invited in, can you still exert the power or the pressure that drove you to get there in the first place?” Another one: Can one be a responsible critic of art with neither artistic inclinations nor a desire to integrate art fully into one’s life? In other words, can one treat art solely as an intellectual endeavor and still understand it?

Resources / Redistribution

With so much of the art world premised on secrecy and the hoarding of information, one of the most important things one can do is freely share one’s access to resources. With no guarantee that what you or I do will prove to be of cultural or historical significance, it behooves us to foster each others’ attempts to achieve related goals. If twenty people are undertaking more or less the same project, the chances are exponentially greater that someone will succeed than if only one person, however capable, forges ahead alone.

Slowness

As we ratchet across the Western (and, increasingly, the Eastern) hemisphere, slowness becomes the province of eccentric geniuses. Charles Ray spends years in a quixotic attempt to cast the interior and exterior of a tree trunk felled roadside. Art historian T. J. Clark passes the better part of a year engaged with two canvases by Poussin; the result is a book with an unexpectedly resonant title: The Sight of Death. But the reverent devotion of these men in fact confers life upon the objects they behold. How can we return the lingering look, the patient construction, to our general repertoire?

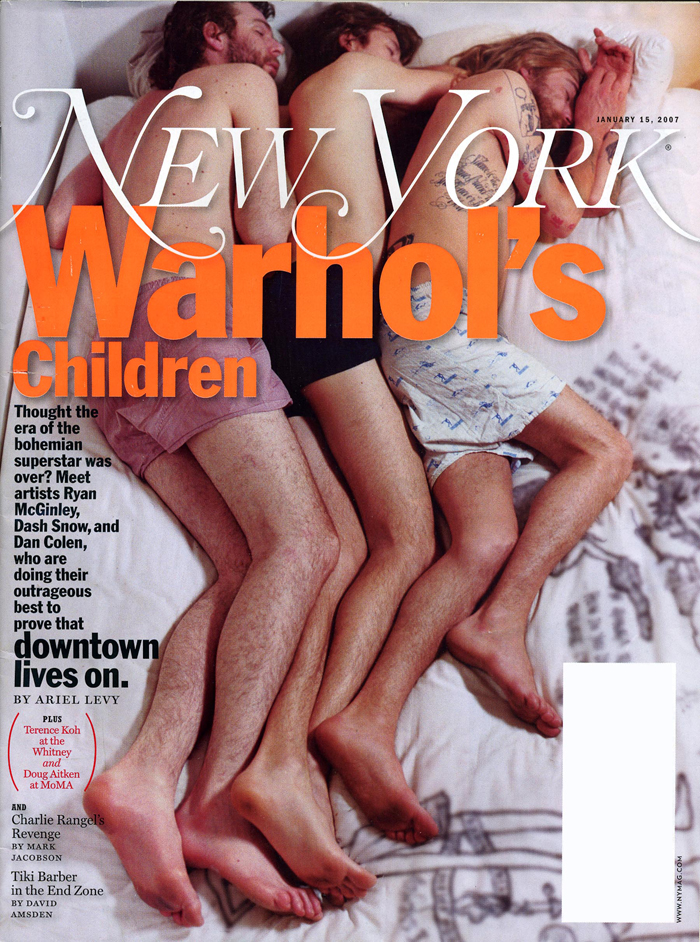

New York Magazine cover, January 15, 2007.

Twin motivations

Short story writer George Saunders, in an interview: “I think it comes down to the motivation of the individual student. If the student writer wants to get over—become famous, dominate others with his talent— then no matter what, he’s going to lose. On the other hand, if he wants to go deeply into himself, subjugate his own pettiness, discover some big truths about life—there’s no way he can lose. And the thing is, we all have both of those motivations within us, every second that we’re writing. So it’s an ongoing, lifelong battle to write for the right reasons.” This is applicable both to artists and their critics.

Ubu.com

Completely independent, completely unconcerned with copyright restrictions, it is a model for how to use technology for the benefit of the widest possible number of people. Ubu.com offers everything from examples of concrete poetry to a web version of the entire run of Aspen magazine, to five complete films by Guy Debord, to a compilation of videos by Pipilotti Rist, to MP3s of a suite of nine seven-inch records with sound effects by Jack Goldstein. One can obtain an education from this website.

Value

How many people writing about art make apparent the criteria according to which they assign artistic value? How many artists are able to explicitly state the criteria by which they consider one of their works a success? Are such statements of purpose any longer necessary?

“Warhol’s Children”

“He had been a lad of whom something was expected. Beyond this all had been chaos. That he would be successful in an original way, or that he would go to the dogs in an original way, seemed equally probable.” (Thomas Hardy) “The youth have always had the same problem—how to rebel and conform at the same time. They have now solved this by defying their parents and copying one another.” (Quentin Crisp)

Xenophobia

We mask discomfort with jokes: “All the hot new Chinese art looks like it was made twenty years ago,” commented one friend recently. As record sale prices are broken, museums sniff around studios, and the press rhapsodizes, one struggles to make sense not only of the explosion, but also of the art. Looking at figurative work by Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang, Zeng Fanzhi, or Fang Lijun, all mentioned in a recent New York Times article, I wonder: Do I dislike it because it looks “foreign”? One need not know an artist’s biography to appreciate an artwork, but what of work from a culture seemingly incommensurable with one’s own?

Youth

“After all, life hasn’t much to offer except youth and I suppose for older people the love of youth in others.” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote this in a letter to his cousin at age twenty. The sentiment resonates in today’s art market, and goes a long way toward explaining its heedless “cradle robbing.” The problem is not the art world’s fixation with youth, but rather the implication that the term is synonymous with value or quality. “Young”—applied to an artist—is (or should be) a neutral descriptor. Artists young and old alike have the potential to make good art, and we should seek and promote good art wherever (and from whomever) it may come.

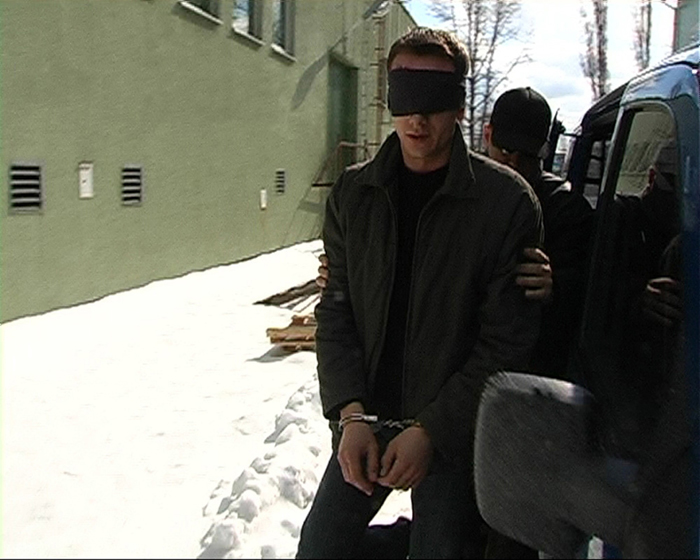

Artur Zmijewski, Repetition, 2005. Stills from film.

Artur Zmijewski, Repetition, 2005. Stills from film.

Zmijewski, Artur

Few artists of international stature make art about the unequal distribution of human health—and health’s subsequent frailty. Many of Polish filmmaker and video artist Artur Zmijewski’s works examine this topic, and do so humanely, which is perhaps the highest compliment that can be paid to unflinching sequences featuring completely paralyzed men, deaf children, or unclothed elderly people. At the 2005 Venice Biennale, his ambition expanded to include psychological relations in a film that re-created the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment. It was later presented at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art in San Francisco, but I cannot think of a Zmijewski exhibition in New York, a situation that I would like to see rectified.

Brian Sholis is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn, New York.