ALEXANDRA JUHASZ: I have been making and writing about AIDS video since 1987 when I joined the fledgling ACT UP and volunteered for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). This was the subject of my first monograph, AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video (1995), where I covered dominant media, my own community-based video at the Brooklyn AIDS Task Force and GMHC, as well as that of my extensive activist media community. In this most recent decade—as was true from the mid-80s to 90s—my thinking and activism about AIDS cultural production has taken place in conversation and community. I recently coedited an anthology with Jih-Fei Cheng and Nishant Shahani, AIDS and the Distribution of Crises (2020), and am a member of a New York City collective, What Would an HIV Doula Do?1 And, I have enjoyed six years of conversation, both in person and in written correspondence, with the writer and cultural worker Theodore (ted) Kerr, who is also a fellow Doula member. Ted recently edited an issue of OnCurating, titled What You Don’t Know About AIDS Could Fill a Museum.2 Our conversations began online in 2013 when I still lived in Los Angeles and Ted was working at the New York City-based arts organization, Visual AIDS.3 This bond formed as we were both noticing and trying to individually make sense of a sudden upsurge of cultural attention to AIDS after a long period of chilling silence.

THEODORE (TED) KERR: The first instance where I felt aware of this upsurge was when I saw Sex Positive, Daryl Wein’s 2008 movie about the creation of safer sex. It was the first time I saw a movie attempting to make sense of AIDS in the past. But, of course, it was not the first. This difficult subject was arguably on your radar a bit earlier, Alex, when you made Video Remains in 2005. Like James Wentzy’s video, Fight Back, Fight AIDS: 15 Years of ACT UP (2004), Jean Carlomusto’s Sex in an Epidemic (2010), Sarah Schulman and Jim Hubbard’s ACT UP Oral History Project (2002–15), Jennifer Brier’s book, Infectious Ideas (2009), or Avram Finkelstein’s thinking around AIDS 2.0 to name a few, you all and so many others were already trying to make sense of AIDS history.4 This steady and building stream of works of remembrance was happening as I, too, saw an upsurge of activity: fielding more calls and emails at Visual AIDS from a cross section of people (young, old, academics, artists, activists) all interested in looking back at AIDS history. This was, at first, exhilarating and exciting. My whole adult life I had been involved in AIDS work in some way, and had often been the youngest person in the room. There was this idea that young people didn’t care about AIDS and that older people didn’t want to talk about it. An emerging interest in AIDS disproved that. But then, I started to have mixed feelings about all the attention that was being paid to AIDS because it was primarily about looking back in time. This I found confusing. I believe in the power of history, but I was excited about having more people join me in feeling and reacting to the urgency of AIDS in the present. I feared that Sex Positive and other films in this vein could leave audiences thinking that AIDS was a thing of the past: experienced, remembered, and mourned by those older than me who had experienced firsthand the devastating early years of the crisis.

JUHASZ: In this very way, the cherry-picked group you list above have much in common. We all had been active in AIDS culture in the 1980s and into the 1990s. We returned in the 2000s in part because we knew we had lived through a productive, intense, if awful, period of AIDS cultural production. We were also only too well aware of so many friends and colleagues who did not make it through, hence my focus in Video Remains on Jim (James Robert Lamb), my best friend, who died in 1993 at twenty-nine. Our backward gaze kicked off a new period of cultural attention that is itself worthy of attention. This is what we have spent the last six years trying to understand.

Alexandra Juhasz, Video Remains, 2005. Video stills. DV video, sound, 55 min. Courtesy of the artist.

KERR: We began together to flesh out what we could mean by AIDS Crisis Revisitation, a phrase I had already begun using for this surprising and growing body of work.

JUHASZ: Together, we catalogued the ways that well-known productions like Dallas Buyers Club (Jean-Marc Vallée, 2013), How to Survive a Plague (David France, 2012), United in Anger (Jim Hubbard, 2012), We Were Here (David Weissman, 2011), and even Philomena (Stephen Frears, 2013), as well as more independent work in the Revisitation vein, like Heart Breaks Open (William Maria Rain, 2011), Liberaceón (Chris Vargas, 2011), When Did You Figure Out You Had AIDS (Vincent Chevalier, 2011), and Bumming Cigarettes (Tiona McClodden, 2012) were all looking at AIDS through the prism of past activism, suffering, and mourning. Until the 2010s, people hadn’t really dealt with the losses, fears, and suffering experienced during the preceding period of silence. We hadn’t been talking, which itself was a definitive aspect of what we call the Second Silence. Sadness, grief, anger, shame (for living on, or not doing enough), PTSD, denial, decline of community, continuing illness, getting better: we all had our reasons for not engaging. Thus, even as work was continuing to be made and even shared during this period, there was rarely the large audience or lively conversation to receive it that had defined the previous period.

KERR: The AIDS community responded with outpourings of remembrances and conversation, as well as critiques. As swift as the Revisitation entered our lives, so, too, came the backlash. Most of the early Revisitation work seemed to be casting the net rather close to home. That is, it was about and by and perhaps even really for gay white men, a community that had been and was continuing to suffer immensely because of HIV/AIDS.

JUHASZ: It was an upsetting and exciting time. The criticism was productive. It engendered more media making, activism, scholarship, and a lot of community discourse, online and off.

KERR: The Tacoma Action Collective’s die-in at the exhibition Art AIDS America at Tacoma Art Museum in Washington in 2015, in response to the lack of Black artists, helped establish a more robust and fully realized exhibition as it continued to travel the United States; and Jih-Fei Cheng’s “How to Survive: AIDS and Its Afterlives in Popular Media”—a critical response to How to Survive a Plague—not only named some of the issues that many of us had with the Oscar-nominated documentary, it also provided a roadmap on how to watch AIDS video going forward by attending to who wasn’t being remembered and what was being valued.5

JUHASZ: Our conversation—with each other, and in community—continued and developed, culminating in this conversation here, hot on the tails of our book manuscript submitted to press in December 2019, We Are Having This Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Culture. To better understand this reemergence of AIDS that was taking up so much space within the public realm, we needed to situate AIDS not just in our tempestuous present, but also more fully in its time(s). And, we needed to do that together because we also found that our own processes were modeling activist engagements with the past that were intersectional, intergenerational, and present-focused.

The bag was created by J. Morrison for Visual AIDS in 2009 as a way to keep the AIDS crisis part of the cultural landscape. Photo: Theodore (ted) Kerr.

KERR: We developed what we call the Five Times of AIDS: a chronological way of understanding the crisis as it ebbs and flows through culture, as well as bodies and communities.

JUHASZ: We offer our five times not as a prescription, but as a lens, a way of seeing and being in time, history, and the future with our primary commitments being in and for the present. Of course, time cannot be standardized.

KERR: We know from our own experiences that it is felt differently by individuals, by the two of us, as well as internally within any person. So, we celebrate the boundaries and interconnections of our times, because we ourselves and, also, we together know them as porous, loose, interdependent, and co-constitutive.

JUHASZ: Periodization has helped us to understand and learn from what is otherwise experienced as both a confusing and overwhelming past and present.

KERR: To do so, we start before AIDS. Pre-1981.

JUHASZ: We call this AIDS Before AIDS. We establish that there is a history of HIV’s impact before the much acknowledged start of the epidemic in the 1980s. A longer view helps us to both make space for unnamed death, but also chart the impact of HIV within the many communities where it has created destruction over its long history. This is what you do so critically in your work on Robert Rayford, a Black teenager who died of AIDS in 1969.6

KERR: The second notch on our timeline is 1981 to 1986, what we call the First Silence. In the early 1980s, medical staff and impacted people—the ill and their loved ones—began to take action around a then-mysterious and escalating health crisis.

JUHASZ: But their work was done primarily in isolation, with federally coordinated efforts blocked by the Reagan administration and abetted by an apathetic or uninformed media and public. The result was that a once possibly manageable health crisis within contained communities became an epidemic.

KERR: Which leads us to the third period on our timeline, AIDS Crisis Culture, from 1987 to 1996. From the ACT UP poster to the community produced video you made and wrote about as well as art in every medium all connecting to historic levels of direct action, this is a period of mass cultural production and discourse leading to social and medical breakthroughs.

JUHASZ: I grew into an adult during (and making) AIDS Crisis Culture. What became clear as we looked at AIDS through our five-time framework is that the majority of what the culture holds up and enshrines as AIDS culture comes from this period. This is what is revisited in retrospectives and remakes, on T-shirts and in memorials. But the amazing work from that period is rooted in the specificity of its time. Our periodization is one way to stay mindful of the differences, changes, and rhythms of AIDS cultural production. Any moving, recognizable image from this time is certainly a testament to hard-won visibility, but may not serve as well as a representation of other definitive experiences of AIDS, like those from the period that would immediately follow, for instance.

KERR: AIDS Crisis Culture, coming from within a period of mass death, mass action, and massive representation, was followed by its stunning opposite: the fourth time of AIDS, the Second Silence from 1996 to roughly the 2010s. The introduction of lifesaving medication in 1996, highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), resulted in better health for many but also a linked decline in the space HIV/AIDS took up in public. But, needless to say, HIV-related activity was ongoing for people and communities. During the Second Silence, living with AIDS became less connected and less visible. It was in this period that I first cut my teeth as an artist and an organizer.

JUHASZ: One of the core differences between us. We began to learn more about time and inspiration, about how individuals enter and stay the course, by accounting for our varied experiences of the very same periods.

KERR: AIDS went on within the Second Silence. People were living, dying, and surviving; AIDS culture was being made; activism was getting done. But what was different was that, within the silence, all of these disparate efforts were not connecting as they once had, so recently, during AIDS Crisis Culture. They were harder to find.

JUHASZ: Well, here’s the thing about silence: it is not absence, it is not lack. Silence is full, powerful, and present. It has wreaked havoc within all the times of AIDS.

KERR: Silence inspired the changes that brought us together. The norms of AIDS were being rewritten again. By 2012, Truvada, as an HIV prevention medication, had been approved by the FDA; and the term U=U (Undetectable = Untransmittable), which refers to the experience of people living with HIV whose viral load is “Undetectable” (rendering the virus nontransmittable through sex) was about to become a game changer.

JUHASZ: For a while, cataloging the AIDS Crisis Revisitation, the fifth time of AIDS, in and of itself was exciting and challenging. “Look, Ted! There’s AIDS in a novel! On Broadway! On cable TV!” For a few years, each appearance came as a delightful or curious surprise that we had to note, write about, and analyze.

Ben Cuevas, Reinserted: Show Center, 2019. Giclée print, featuring the archive of Annie Sprinkle, 60 × 40 in. Courtesy the artist.

KERR: Until we didn’t. Our analysis and criticism, as well as that of so many of our peers also reckoning with AIDS cultural production, was engendering conversation, critique, and also more AIDS culture, including in this very publication. One of my favorite pieces of writing to emerge out of the Revisitation is Dont Rhine’s 2013 X-TRA essay, Below the Skin: AIDS Activism and the Art of Clean Needles Now.7 There is not enough cultural production about drug use, Los Angeles AIDS activism, or the positive contributions of active drug users. Dont’s piece has all of that and more. It is a personal account of a life changing time about lifesaving tactics that is full of details and names. Reading it, I could mourn, learn, and think about how to apply what I was reading to the present.

JUHASZ: As more and more AIDS culture entered the world, and that began to seem less and less important in and of itself, we found space to wonder about new things: where and when does the Revisitation stop and some new phase begin?

KERR: Right. For example, much was being made of the fact that season two of the groundbreaking TV show Pose (2018– present) includes reenactments of videotaped records of ACT UP meetings and demonstrations, all the while putting Black trans women at the center of the narrative. Revisitation, but differently: responsive, inclusive.8 In fact, it was in talking about Pose while writing a draft of our book (and an essay for the journal, First Mondays, set to come out later in 2020) that we came up with a possible sixth time, AIDS Inclusive Culture (2010–ongoing), which we think is about the ways in which AIDS moves beyond neglect or spectacle. Perhaps this time is a point in AIDS history where the inclusion within the national narrative can be, and sometimes is, respected and intersectional.

JUHASZ: And while we are still deep in conversation about where we are now and where we will be going particularly in relation to our thinking around AIDS Inclusive Culture, what is clear is that the Revisitation was producing its own corrections. Which led to a new question for us, given our primary focus on the Revisitation: Could there be contemporary AIDS culture that didn’t revisit? I thought no. But then we saw a play together on World AIDS Day 2019, with our fellow AIDS cultural worker Alex Fialho. In one in two (2018), Donja R. Love, an artist living with HIV for a decade, explores the experiences of Black queer men living with HIV in the era of PrEP and U=U. Before I saw the play I had gone to the mat (with you) arguing that every piece of AIDS culture must be part of the Revisitation because no one can escape AIDS history: whether we acknowledge or even know the past of HIV, it haunts our daily experiences through encounters laced with affect or acts organized by stigma, desire, or pride, for example.

Donja R. Love, one in two, 2018. Performed by Jamyl Dobson, Leland Fowler, and Edward Mawere; directed by Stevie Walker-Webb; produced by The New Group at The Pershing Square Signature Center, November 19, 2019–January 12, 2020. Photos: Monique Carboni.

KERR: But I wanted to leave space in our imaginations for the possibility of AIDS culture that could be fully, firmly rooted in the present. This was inspired by two things: A Strange Loop (2019), a play by Michael R. Jackson that had its world premier at Playwrights Horizons in New York, last year, in which the main character was dealing with the reality of being a Black Queer person in the age of hookup apps, Tyler Perry, and HIV; and the 2015 AIDSrelated storyline on Shonda Rhimes’s ABC drama, “How To Get Away with Murder,” that so deftly handled AIDS in the twenty- first century. Both Jackson’s play and Rhimes’s show feature characters wrestling with the impacts of HIV, not loaded down by the past as a means of justification. HIV is considered in the context of the twenty-first century, within the reality that people are still being diagnosed and also dying with HIV in the present.

JUHASZ: When we first started talking about this aspect of contemporary AIDS culture, I was trying to make sense of how Trump had so casually mentioned his aim to end AIDS during his State of the Union address in 2019. Perhaps there really was an emerging form of AIDS representation rooted in our newfound representational abundance, and how all this new work aligned with another chapter in this history, one also being expressed often and loudly: a (perceived) closing down, in the form of the much-heralded “end of AIDS.”

KERR: The “end of AIDS” is something that splits AIDS activists as a goal or even near-term possibility. While we all yearn for this as a future, we suggest that these contemporary claims paper over how AIDS stays present (even when undetectable), and simplifies its presence to merely being a matter of medicine or biology.

JUHASZ: Even after a cure, AIDS will be with us as loss, anger, fear, oppression, and culture.

KERR: You suggested that this ever more common and casual mention of a disappearing HIV might be an example of AIDS Normalization, made possible by a ramping into visibility via Revisitation.

JUHASZ: We couldn’t go from Silence to Normalization without a good long look back, a review, if you will, as well as a long-overdue reckoning of how we got to this point in history as it relates to AIDS, how all that felt, what it did and does, and what it meant that we are still here, as is AIDS.

KERR: And I think that is why Love’s one in two was so important for us. The three Black gay male actors are playing a game where a rule is that one of them will end up with HIV. I liked that the play was pushing back against the tyranny of statistics by refusing to have two people on stage, but rather troubling numbers by adding a third. This seemed like a structural way to indicate a challenge to the stories we customarily tell about HIV. Near the end of the play, when the plot seems to be barreling towards a lead character having to make a choice between assimilation or annihilation, we are saved from such a scenario and the game stops, and a new way forward, a new plot—

JUHASZ: A new story.

KERR: —is offered. So here was a play that was actively not looking back, and instead was figuring out a new way to be in the present (and future) with HIV.

JUHASZ: But, in watching the play, together and within our community, it was impossible not to put Love’s present-focused work in conversation with the past.

KERR: Right. But I think what we are learning right now, in real time, is that Normalization does not have to be separate from Revisitation (or Inclusion). No time is a tomb, and, in fact, our times of AIDS live alongside each other. Maybe part of Normalization is not just that AIDS can stand on its own within a present day context, but, more so, an ongoing reckoning with AIDS can and should be a normal, included, and expected part of culture.

JUHASZ: Of the past and the present. And this is so powerfully rendered in On Our Backs: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work, curated by Alexis Heller for New York’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, which was on view from September 2019 to January 2020.

KERR: But the exhibition is about sex work.

JUHASZ: And so much more, including HIV, since the AIDS crisis so deeply impacted and impacts this community. And, as is true for many queers and our sex-positive allies, the dangers and harms, but also the cultural empowerment AIDS demanded, initiated many of the artists here into voice and community.

KERR: As the show so clearly documents, AIDS was part of why and how radical sex workers began to make claims and demands about their labor and culture.

JUHASZ: The impact of AIDS is rife, understated, and present across the show. One of so many examples is the three covers of Black Lace magazine (1988–94), an “erotic publication, created by and for Black lesbians,” displayed in a row in a vitrine.9 The first one obscures the face of its subject, although the figure has black skin and a few long dreads catching a flare of light, and instead makes most visible her “Silence = Death” shirt. The second cover features a close-up of a strong Black femme and the third centers the figure of a Black butch. AIDS is incidental, the point, connected and connecting, contextual, motivating, and yet unnamed.

On Our Backs: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work, installation view, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, September 28, 2019–January 19, 2020. © Angus McIntyre 2020. Courtesy of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Angus McIntyre.

KERR: What I liked about these magazine covers in the exhibition is that they exemplify something we have been writing about, most specifically in our piece, “Who are the Stewards of the AIDS Archive? Sharing the political weight of the intimate.”10 We center cultural production that is rooted in the everyday, complicated, hard-to-capture experiences of the most silenced individuals and communities.

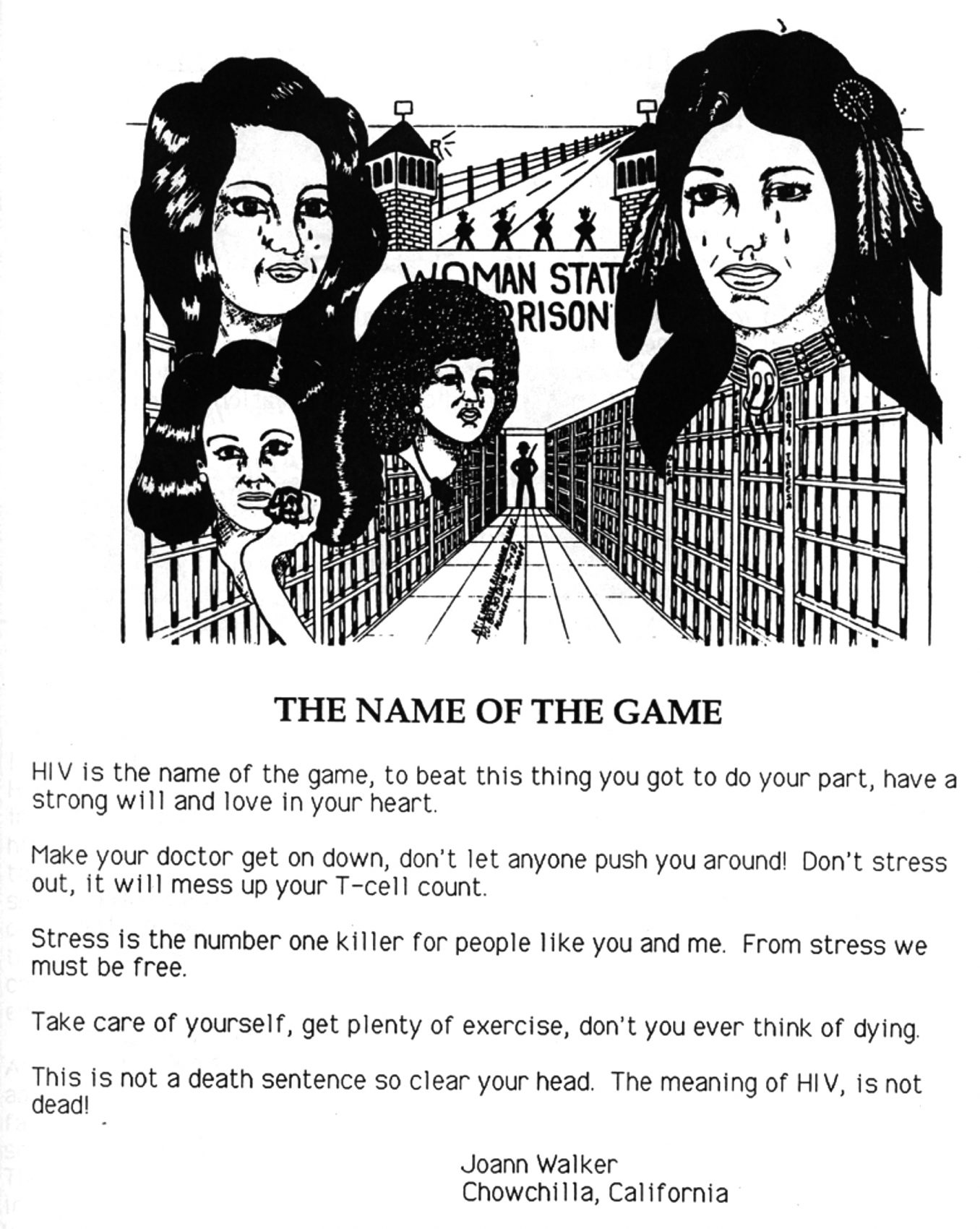

JUHASZ: Yes, we’ve been eager to learn from representations of AIDS history and culture that foreground women, people of color, trans people, poor people, and sex workers: communities so hard hit, so activated, and still so under seen. With Jawanza Williams and Katherine Cheairs, as members of the What Would an HIV Doula Do? collective, we co-curated Metanoia: Transformation through AIDS Archives and Activism, on view at The Center in New York in the spring of 2019, and until late April 2020 at the ONE Gallery in West Hollywood. We use holdings from the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries and The LGBT Community Center National History Archive to explore AIDS activism accomplished by Black women, such as Joann Walker and Katrina Haslip, that changed the world and AIDS, all done from within prison walls. What we learn from Heller’s show and our own experience with Metanoia is a focus on the politics of living gets us both inside of and beyond questions of racial representation. Looking at AIDS through the cultural production of women in prison or sex workers are thematic, political approaches that forefront marginal, if radical and powerful, experiences and politics of the crisis that include those of gay white men, even as theirs are not the primary point of view.

Joann Walker, The Name of the Game, c. 1990s. Flyer for the Coalition to Support Women Prisoners at Chowchilla, designer unknown. Ink on paper, 8 1/2 × 11 in. Judy Greenspan Papers, The LGBT Community Center National History Archive, New York.

KERR: Right. Thus, aside from the magazine covers, for me, some of the most moving artifacts in the show come from the early life of Richard Berkowitz, who was at the show’s opening (!), the subject of the film Sex Positive I mentioned earlier as the first example for me of the Revisitation. In his memorabilia, we see the early labors of a white gay man—a much-in-demand dom in his day—who, because of AIDS, was working to teach johns how to treat sex workers with dignity, and then, along with Michael Callen (and Dr. Joseph Sonnabend), took on another critical project: how to see community, mutual affection, and care as harm reduction tools during the period we name as the First Silence of AIDS.

JUHASZ: Seeing his papers and sex paraphernalia alongside the work of other pioneering sex workers, like queer feminist friends and colleagues Annie Sprinkle or Carol Leigh, for example, is an exciting intersectional model for how to do AIDS cultural work as Normalization.

KERR: When multiple histories, identities, and experiences come together, there is less of a burden placed on any one group or moment to represent the complex assemblage that is the ongoing AIDS crisis. A multiplicity of HIV-related experience, cutting through and connecting some of our periods, is on view with great beauty in the Through Positive Eyes project currently showing at The Fowler Museum at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Over ten years in the making, it is both a book and an exhibition, co-curated by David Gere, UCLA Professor of World Arts and Cultures, and photographer Gideon Mendel. In the version I saw, selfies, portraits, short videos, and text provided as many examples of life with HIV around the globe as there were faces in the exhibition. Texts on the wall include people talking positively about bareback sex; young people sharing their HIV coming-out stories to their parents only to find out that they, too, are living with the virus; middle-aged people reflecting on the stigma they have endured at the doctor’s office; and so much more. Through accumulation, the stories provide a network of AIDS. A form of Normalization emerges, less attached to normative behavior or similar experiences or times, but rather to connection across difference.

JUHASZ: Specificity alongside multiplicity makes it possible for people to locate themselves and their times within a complex cultural experience. Carol Leigh was one of three advisors on the exhibition (along with Yin Q and Ceyenne Doroshow). I worked with Carol in the 1980s for GMHC’s cable access show, Living with AIDS (my early volunteer work mentioned at the beginning of this conversation). I feature her art and activism in my second half-hour show for the series, “Prostitutes, Risk and AIDS” (1988). On Our Backs gives space to many feminist sex workers who, like and along with Carol, came into their radical intersectional sex-positive feminist queer politics through the indignities and inconsistencies exacerbated by AIDS.

KERR: I like that moment of personal connection.

Beth Stephens, Who’s Zoomin’ Who?, 1992. Silver gelatin print, 29 1/2 x 30 1/2 in. One from a series featuring Stephens with Annie Sprinkle. Collection of Sprinkle & Stephens. Courtesy the artist.

JUHASZ: My own histories and connections across the times of AIDS felt so resonant and evident on the show’s many walls—another reason why intergenerational interaction about AIDS culture is so critical. Different things will move us, speak to us, be resonant. I was actually stopped cold by one image that seemed to have emerged from my own memory, as if spit out from a magical 3D printer… The show includes a realistic painting, Hanky Panky (1980) by Patrick Angus. The painting depicts a place with which I held only a passing familiarity but it has haunted my own dreams and writing. Do you know my story about the Gaiety, Ted?

KERR: I don’t think I do.

JUHASZ: You know that while I became an AIDS activist almost as soon as I arrived to New York in 1986, the death of my best friend and first love James Robert Lamb at twenty-nine in 1993 cemented my commitments, broke and motivated me, and has kept me responsible to AIDS history and activism for all the decades following.

KERR: I do know this.

JUHASZ: I’ve also told you that Jim was a sex worker, on and off, as well as being a go-go dancer, and also a member of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company. But when I was still a girl, maybe twenty-one, and pretty much unaware of sex, let alone homosexuality, sex work, or AIDS, I spent a romantic weekend with Jim in a beautiful apartment that he rented for us on Jane Street in the West Village. I was a senior in college in western Massachusetts but he had dropped out and was living in New York. On one night of our getaway, he told me he had to leave to go to work in Times Square. I knew so little of New York City. We went to school in New England and I was from Colorado! By that point, I did know he was working as a stripper. But what I understood of this was vague and naive. It didn’t include the sex that was for sale in the Kick Off Lounge next door to the main stage (and pictured by Angus). This is how he made the money to afford dreamy vacations with me in the big city!

Patrick Angus, Hanky Panky, 1980. Acrylic on canvas, 40 1⁄2 × 54 1⁄4 in. Collection of the Leslie-Lohman Museum. Courtesy of the Estate of Patrick Angus.

KERR: How did you find this out?

JUHASZ: About an hour after he left our room, I followed him to Times Square and climbed the rickety steps that led to the now-infamous burlesque theater. I paid my entry to a heavy woman at the door. She gave me a wry once-over. I walked in and saw just what is recorded there in that realist rendering by Angus, who, like Jim, died of AIDS (in 1992) before the cocktail could save either of them. I saw the tattered seats and isolated men. I saw that speckled ceiling and dirty walls. I saw my best friend dance and strip. He was really sexy. He was acting, playing the buff college co-ed. Thighs and abs built to perfection, eyes demure and then engaged, on his rhythm. He was in control, in his body, in that room, showing a different part of himself never available to me. The room was tawdry, the men wanting, and Jim was centered.

KERR: What did he think about you watching him?

JUHASZ: I never told him I was there. Or, actually, I didn’t until 1993 when he was dying.

KERR: Why not?

JUHASZ: My ideas about AIDS, sex work, homosexuality, the closet, they were all live there, in that room, and then in my memories—and they still are, although differently, as I’m now a world-weary fifty-five! A woman who grew into this knowledge through time, and AIDS, sex, sex work, feminism, queer art, and Jim’s untimely death. And this is all there in that painting, and the art show. AIDS: Central. Formative. Named and not. When I watched Jim dance, he didn’t yet have HIV and I wasn’t an AIDS activist. It wasn’t live for us internally or visibly or politically. And yet, I know that it framed all encounters that humans could have with each other in those times, with those we loved, with the world. As it does now.

KERR: And here we are now, decades later. Jim is still with you, with us. You don’t need art or culture to remember him. Yet, I must say, I am grateful to Patrick Angus’s painting, and Alexis Heller’s curation, for creating the opportunity to share that story about you, Jim, the past, and the present. How we can know things about ourselves and the world is often as important as the facts themselves, no?

JUHASZ: Yes.

On Our Backs: The Revolutionary Art of Queer Sex Work, installation view, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, September 28, 2019–January 19, 2020. © Kristine Eudey, 2019. Courtesy of the Leslie- Lohman Museum of Art. Photo: Kristine Eudey.

KERR: And when we share stories, when we look at art together, when we encounter history as a collaborative project of shared knowing across difference, we are creating new invitations to know and learn, and know and learn better. Implicit in our relationship as writers is invitation. You are someone who often invites collaboration, and I am one of the lucky people you extend invitations to. Inspired by that, together, we invite each other to think about AIDS now: What does silence mean? What are the parameters of Revisitation? For that I am grateful.

JUHASZ: I am grateful too, and the way we can pay each other back is by extending the conversation and working against calcification. Alexis does this in her exhibition: a cultural production about AIDS that is not bound by time or even AIDS. It expresses people, tactics, relationships, politics, and loves between the past, the present, and the future.

Dr. Alexandra Juhasz is Distinguished Professor of Film at Brooklyn College, City University New York (CUNY). She is a longtime AIDS activist videomaker as well as the author and editor of scholarly books, including the forthcoming My Phone Lies to Me: Fake News Poetry Workshops as Radical Digital Media Literacy (The Operating System, 2020); and AIDS and the Distribution of Crises (with coeditors Jih-Fei Cheng and Nishant Shahani, Duke University Press, 2020).

Theodore (ted) Kerr is a writer and organizer. Kerr teaches at The New School in New York, and is a founding member of What Would an HIV Doula Do?