Mary Kelly, Flashing Nipple Remix, #2 , 2005. Black and white transparency in light box. 38 x 48 x 5”; Edition of 3 + AP. Photo: Grant Mudford. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

Mary Kelly’s recent installation, Love Letters, shines a meditative light on the meaning and legacy of the Women’s Liberation movement. Composed of four parts originally shown in New York in 2005, the installation is a sort of magic square, with each direction mirroring the others but also striking into territory all its own. Collectively, these four parts move from meditation to intervention. What emerges are four articulations of a question so powerful that no single narrative, artwork or theory can contain it: the meaning of feminism today. Unlike the magic square however, the sum of the numbers is different in every direction, and each trajectory leaps off to a new place. While this work is grounded in critical thought, its effect is anything but theoretical; instead it foregrounds a relationship between theory and everyday life that was so characteristic of feminism in the first place.

The juxtaposition of text and image has always been a hallmark of Mary Kelly’s artistic practice; this duality allows the work to resist both storytelling and representation, foregrounding neither a totalizing narrative nor master image. Text and image serve as propositions and indexes, forging a dialogic work that reflects Kelly’s strength as both a writer and visual artist. Love Letters is a masterful amalgam of image and text that, while avoiding representation, hardly skirts ideas and even polemics. The two text pieces of the show, Sisterhood is POW… and Seemed Right, are counterparts, the first being a poetic evocation of a 1971 London protest (in which Kelly participated) against the Miss World contest. Set in black Lucite with cut- out cursive lettering much like handwriting, illuminated simply and effectively from the wooden shelf below, the text invokes the heady spirit of the Miss World protesters: “arms locked, hands /firm, fingers longer, /more lucid, flash /luminous nipples and /crotches at fans in /chauffeur-driven vans.” Each stanza is set into a rectangle of 20” x 15” Lucite, with roughly each third phrase accented in a 24” x 20” piece. The rhythm is in a beat of three—a waltz or a lyric—a text set hypnotically across three walls. The pointed finger emerges as the dominant metaphor, signifying both autonomy and defiance.

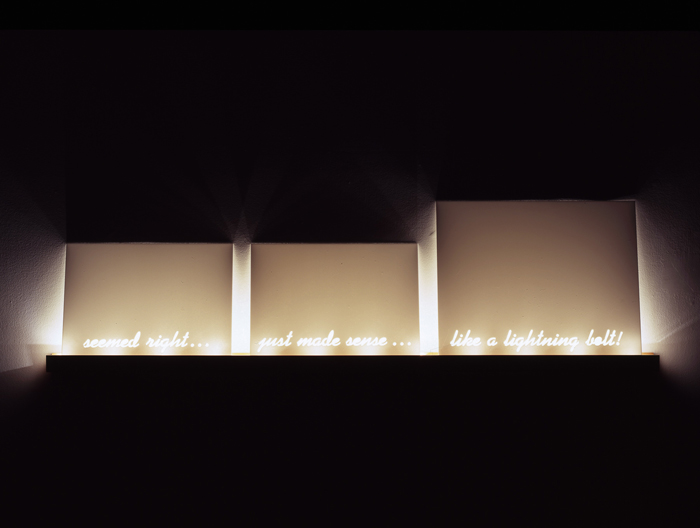

Sisterhood is POW… echoes both feminist power and the prisoner of war: just as the war is not yet over, neither has the question of feminism and social change been put to rest. The far shorter Seemed Right, its textual counterpart, consists of found text, the words of other participants in the Women’s Liberation Movement: “seemed right…/just made sense… /like a lightning bolt!” Set in white Lucite in the same lettering and mounting, this text operates both on allusion and evocation, stressing the dually natural and revolutionary character of that decade’s transformation of gender politics. As with many revolutions, it appeared to its participants as both inevitable and powerfully transformative. The empty space of the cut-out words in these text pieces is sharp and luminous, a play on both the absence of these long-ago events and their haunting afterlife.

The two image pieces in Love Letters take on the same issues completely differently. “WLM Demo Remix” is a video loop that transitions over 90 seconds between two images—an iconic Life magazine photo of a Women’s Liberation Movement demo in August of 1970 and Kelly’s 2005 restaging of it with her students. Spending most its span in a grey cross-fade of generations, the past is never fully “revealed” and the loop soon begins again. The original Life photo is both full and empty, an authentic representation of popular protest and its commodification by a national magazine in a seamless image. Kelly’s remix is all seams, neither photo nor video, a redeployment of historically lodged ideas on gender.

Mary Kelly, Flashing Nipple Remix, 2005. 3 black and white transparencies in light boxes. 38 x 48 x 5 inches each. Edition of 3 + AP. Photo: Grant Mudford. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

Its visual counterpart in the show is “Flashing Nipple Remix,” Kelly’s restaging of a protest in which women fixed flashing lights to their crotches and breasts at the afore-mentioned 1971 Miss World protest. Three black and white transparencies in light boxes show the women first standing still, then moving slightly and finally almost dancing, their lights forming streaks reminiscent both of writing and crossing out. This writing of the body has a different valence than the two text pieces. Highlighting our culture’s most evident markers of gender difference—breasts and genitals—Kelly’s luminous transparencies are both a reading and a rewriting of the past, a way to both cite its historicity and the persistence of the gender issues.

These four pieces are a tightly knit matrix of accumulation and distillation, contrasting photography with video, language with representation, and found with poetic texts. The strong monochromatic aesthetic, along with the combination of technical elegance and the handmade, invites reflection on the metaphysics of presence and absence: the haunting persistence of both history and ideas. They play on self-consciousness and reflectivity in contrast to spontaneity, the eruption of both protests and revolutionary social ideas. Love Letters is less nostalgic than polemical: it abstains from the evocation of an idyllic historic moment of resistance by posing it as a question on the role of feminism today. If nostalgic, this work deploys nostalgia strategically.

In our quiescent time, the culture of protest is all but dead. Kelly’s aim is not to monumentalize a moment of history, but to instrumentalize it: to keep the ideas of feminism, women’s liberation and gender theory in active deployment. Feminism here is not only a set of cultural theories, but also a lived history. That the personal is political has been understood from Susan B. Anthony and Margaret Sanger to Emma Goldman and Alexandra Kollontai, but the phrase itself came of currency around 1970. Not since her groundbreaking Post-Partum Document (1973-1979) has Kelly’s own work been as personal. While Document is a painstaking analytical archive of motherhood and femininity, Love Letters is light and allusive, returning to some of the same questions in a highly refined form. There is something uniquely warm and optimistic about this new work.

Mary Kelly, Seemed Right, 2005. 3 units, laser cut cast acrylic, linear strip lighting, wood support 15 x 20 and 24 x 20 inches each, 6 feet overall. Edition of 2. Photo: Grant Mudford. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

From the failure of the Equal Rights Amendment to the recent attacks against abortion rights, few could have predicted the backlash against feminism after the 1970s; even Robin Morgan’s bestselling book Sisterhood is Powerful is now out of print. Whatever one might define as the ultimate goals of the project of feminism, we are further from those goals than once appeared possible. At its core, Love Letters deals with a history that connects both the lived experience of women and the powerful theories that both interpreted and were deployed to change the conception of women’s lives. The installation resists being a mere illustration of ideas, and the use of text and image that defy the relation of image and caption is integral to this. This work echoes a moment in time when enormous changes not only seemed possible but imminent.

A conceptual artist whose work has been informed by psychoanalysis and critical theory, Kelly strives to not to make work that simply illustrates ideas—foremost by avoiding storytelling and representation. A fellow traveler of the generation of artists who filled walls with texts that in many cases might have served better bound in books, Kelly’s use of text is exemplary in its economy and poetic power. Few of Kelly’s projects have been absent of text, and even in works which are purely visual, the images themselves often enact textual questions, such as the re-presentation of absent presence through human technologies (such as language and representation): the images themselves are discursive.

Mary Kelly, Sisterhood is POW…, 2005. 36 units, laser cut cast acrylic, linear strip light, wood support; 15 x 20 and 24 x 20 inches each, 72 feet overall.

Installation view. Photo: Grant Mudford. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

Love Letters poses questions about iconic performances similar to those posed recently by Marina Abramovic in her recent restagings of renowned pieces of performance art at the Guggenheim in New York. “Flashing Nipple Remix” restages but also reframes an activist protest from 1971 and sets it into an art gallery context. Interestingly, the demonstration in 1970 (photographed in Life) in “WLM Demo Remix” was to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed women the right to vote; this amendment itself was brought about in part by a suffragette group called the Silent Sentinels, who protested in front of the White House for 18 months starting in 1918. Thirty-five years after its publication, Kelly has restaged the Life photograph with a group of her students at UCLA. By moving these acts from the street to the gallery, Kelly’s restagings ask us to consider the relation between the aesthetic and the political. These two works suggest that some performance pieces not only can be revisited but seem to require it. They propose that the culture of protest might serve us better right now than the power of introspection, and that protest—from gestural stance to premeditated self-conscious staging—is a form of performance art.

The question of absence and presence haunts Love Letters. Most love poetry is written not to celebrate the presence of love and the beloved but to examine their absence, so we might ask if this is true as well of Kelly’s installation. The love letter here is between generations, fusing the concerns of the public and the private. It is a love letter to the past and to the future that affirms the role of protest in our culture. Love and the libido is a bonding force. All the pieces here work with light and luminosity, light shining through plastic space or celluloid, materials as meaningful as the content, either textual or photographic. All of them play with distance and proximity to experience but also history; presence and absence are both operative in image and text. History is many things, both emotional and instrumental. It’s a restaging of information from the past in the present, and also, in more romantic terms, history can be seen as a kind of persistent illumination, shining through time to illuminate the present.

Matias Viegener is a Los Angeles based writer who teaches at CalArts in Critical Studies and the MFA Writing Program. He is one third of the art collective Fallen Fruit. With Christine Wertheim, he is the co-editor of The Noulipian Analects (forthcoming) and A Séance in Experimental Writing.