Entering Allen Ruppersberg’s You and Me or The Art of Give and Take is not unlike entering a circus sideshow, with banners and flyers on every wall, clashing colors, and images drawn almost entirely from popular culture. The circus references include two large, vintage Cole Brothers circus posters, and a polychrome installation in the center of the space that recalls nothing so much as a circus ring. The exhibition at the Santa Monica Museum features two new, large-scale installations surrounded by several drawings and collages made in the mid to late 1980s. The new installations divide the room on either side of a diagonal, free-standing wall. While the work on the perimeter is more constrained, there is a continuity of themes, graphic styles, and moods. It’s as if the carnivalesque confronts any austerity we might expect from Conceptual art with humor and abundance.

Much of Ruppersberg’s graphic aesthetic arises from his love of American vernacular design from roughly the 1920s to the 1970s. Ruppersberg revels in populist spectacle as a counterpoint to the stripped down, sans serif design aesthetic of mid-century modernism. The overall graphic look mixes handmade craft, amateur snapshots and family portraits with the low-tech, “un-designed” look of older LP covers, sheet music, pulp novels, and four-color magazine ads of consumer objects “as seen on television.” Rather than telegraphing “design” or “modernity” to the viewer, the graphic presence of these two installations signals the colloquial visual language of commonplace, mid-century America, the world of everyday life and ordinary objects that appear to people as they expect to find them.

Allen Ruppersberg, The Never Ending Book Part Two/ Art and Therefore Ourselves, 2009. Installation view at the Santa Monica Museum of Art. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Bruce Morr.

What is it about this image of America that interests Ruppersberg? Is it its modest aspirations, its cheer, its wish to comfort and stimulate us with a clowns, sunsets, cottages, flowers, pin-up girls, puppies, waterfalls, coffee pots, and upbeat religious icons? The excesses of delirium and gloom—or politics and critique—in this most extreme century are subdued but not annihilated: they hover quietly behind the work. Perhaps the most recurrent set of questions underlying the work are quite ancient, those of the relationship between words and images, between language and symbols. Few artists have gone as far as Ruppersberg with such an investigation, making a carnival of the familiar tropes of Modernism and Postmodernism. His aesthetic is accretive and generous, though some of his earlier work here is quite stripped down. The work’s wittiness is something we expect from West Coast Conceptual art, which is often more droll than the solemn intellectualism of, say, Joseph Kosuth or Sol Lewitt. But we’re never certain how ironic or sincere Ruppersberg’s pieces are meant to be.

The most complex installation at the center of the gallery, The Never-Ending Book Part Two (2009), is subtitled Art and Therefore Ourselves: Songs, Recipes, and the Old People. It consists of hundreds of color photocopies mounted on a large, free-standing wall surrounded by countless open boxes of still more photocopies, which are offered to visitors who are exhorted to take them—“Free! Free! Free!” The photocopies, totaling over 15,000, include album covers, old family portraits, postcards, sheet music pages, and newspaper clippings, many of which include readers’ recipes. Sometimes the color copies present whole images and sometimes only enlarged fragments, as if the platen on the copy machine reset itself randomly, or according to some mysterious and now unreclaimable logic.

High on the wall is a banner that says “Wave Goodbye to Grandma,” which underlines the fraught nostalgia of the piece, the sense that the comforting world of “the old people” is disappearing and not much good is taking its place. Underlying is the message that art can offer some kind of consolation, rather than be a tomb or monument to traumatic loss. Ruppersberg’s work is the opposite of heroic; his populist images are not played against for arch or camp effects. While alluding to the infinite or never-ending, the installation remains incomplete. Redemption or salvation through art is out of the question, but through its warmth and humor, art consoles us.

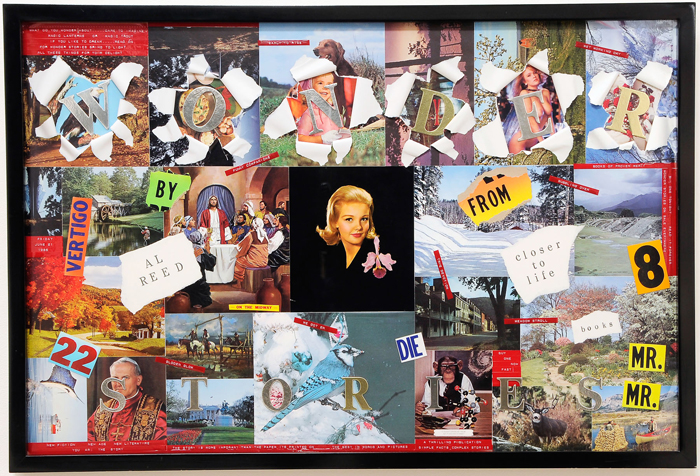

Allen Ruppersberg, Cover Art (Wonder Series), 1985. Mixed media collage, 40 x 60 inches. Collection of Dean Valentine and Amy Adelson, Los Angeles. Photo: Bruce Morr.

Informational labels tell us that the visual material is drawn from Ruppersberg’s vast collection, which he playfully calls “The Archive of Unknown Poetry.” Gathered from garage sales and auctions, the materials attest to his interest in ephemeral culture, especially in its common, unbranded forms. In this sense, “The Archive” is a commentary on the unrelenting progress of modernity: the endless erasure of old novelties to make room for newer, better, and flashier ones. The diaspora of everyday life is emphasized by the provisional look of The Never-Ending Book; cardboard boxes are loosely arranged on multi-colored furniture, as if the entire world has become a traveling carnival of dispersal.

Like other pieces in the exhibition, The Never-Ending Book Part Two engages “the good life” in its heightened moments: meals with families, songfests, viewing inspiring sights. This is the not-so-ordinary everyday, beyond the world of the regular into that of the special. Art often deals with the exceptional and/or the ordinary, but Ruppersberg’s work centers on something else: the role of common specialness. Wonder appears in its familiar forms—the populist spectacles of sentiment, oddity, and nostalgia. At the same time, the work persistently evokes people’s ordinary struggles. Some of the materials in the installation that come from the Great Depression—including recipes for how to make biscuits and gravy, and soup out of stones—have a poignant echo today.

Ruppersberg’s archive of music, image, and text is overwhelming, excessive, and chaotic. Its lack of structure lends his work its poetry: each individual element is a part aiming towards an unattainable whole, which is the experience of the recent past, and perhaps by association, the present moment as well. However, in viewing the work the spectator does not feel overwhelmed, but rather suffused pleasantly and paradoxically with both strangeness and familiarity.

There are several kinds of books in The Never-Ending Book Part Two: the idealized book—a great imaginary tome that can contain everything; and the scrapbook, like the one each visitor may produce from the photocopies she chooses to take away from the show as souvenirs. The never-ending book is the one we all collectively produce. It echoes the book God might keep in heaven, with all our names and everything else inside it. Our shared compilations differ from the Great Book in that they are participatory, variable, and always unfinished.

Record albums are another kind of collecting device. As part of The Never-Ending Book Part Two, Ruppersberg produced a vinyl LP that acts as an aural analog to the images and text. You can listen to the LP through headphones in the exhibition. It includes old songs and hymns, spoken word recordings of poems and recipes, and what sound like families singing around the piano. The record is offered for sale in the museum, and a handful were given away by the artist to viewers who brought in their own old albums, clippings, and photographs.

The Sound and the Story/The Hugo Ball Award for 20th Century Graphics (2009) is an even more musically focused installation. On the obverse of the free-standing wall, it features a floor-to-ceiling pegboard hung with laminated photocopies of sheet music, 78-RPM records, and album covers from punk to folk to ‘40s swing that can be rearranged infinitely. Visitors are invited to reshuffle the materials to create their own constellations and narratives. Ruppersberg himself “plays” the wall periodically, creating a sort of visual composition with the audience as his fellow composers. Ruppersberg’s democracy is reflected in the exhibition’s title, You and Me or The Art of Give and Take. Tapping the depth of our common relationship to popular music is especially powerful in this regard, and it breaks whatever spell of high art might linger in the museum.

Ruppersberg’s wall works from the 1980s look on the two newer, participatory installations in the center like old spectators watching their younger siblings cavort about. Cover Art (Wonder Series) (1985) is the most polychromatic of these two-dimensional pieces, with magazine covers, postcard images of wildlife, landscapes, the Pope, pin-up girls, and representations of Jesus and his disciples arranged in a grid. The top row of pictures is torn open to reveal others beneath, along with metallic letters spelling W-O-N-D-E-R. Cut-out words and familiar old DYMO embossed labels spell out phrases like “the story is more important than the paper its [sic] printed on.” Poised somewhere between kitsch and camp, Cover Art relies on a play between image and text, what is shown versus what is said. There may be a trace of irony here, but it does not mock its own origins. Instead, Ruppersberg invites the viewer to wander into wonder.

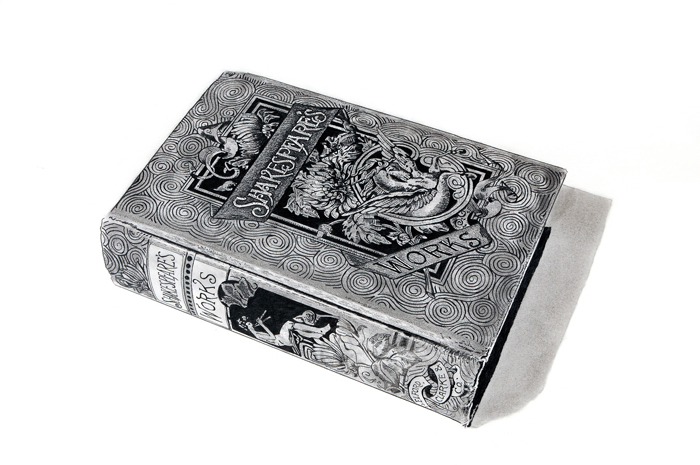

Allen Ruppersberg, The Gift and the Inheritance (Shakespeare’s Works)(detail), 1989. Pencil on paper, 22 1/8 x 25 1/2 inches. Collection of Lenore and Bernard Greenberg, Los Angeles. Photo: Bruce Morr.

Books have figured prominently in Ruppersberg’s work since at least the early 1970s, first with his longhand transcription of Walden from 1973, entitled Henry David Thoreau’s Walden by Allen Ruppersberg, and the monumental The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1974). This exhibition includes examples of Ruppersberg’s well-known series The Gift and The Inheritance (1989). Each is a careful pencil drawing of a book that the artist owns; the four on view here are Shakespeare’s Works, Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, Horatio Alger’s Strive and Succeed, and a Tick Tock Tales comic. Beside each one, the wall label informs us that the drawing comes with a pledge by the artist to bequest the actual book upon his death to the owner of the drawing. Give and take indeed.

Twins (1989), features a pair of two delicately rendered, separately framed drawings of books: Patrick Quentin’s My Son, The Murderer and The San Quentin Story. The humor of the piece circulates through the misreading of these disparate, unrelated Quentins, and the closely related words “son” and “san.” Both books are paperbacks from the mid-1950s with sensationalized covers. Twins reflects on its subject matter—crime, detection, and punishment. But it also reveals our seduction into the true crime genre, which is based on our wishes to see the “real” world reflected back to us in representations, whether through the second-hand remove of the world as related in books, or the third-hand remove of these books as described in Ruppersberg’s simultaneously dazzling and flat-footed commercial illustration drawing style. Beneath the sketch of My Son, The Murderer are the words “Reading Time: 7 Hrs. 15 Min.”; beneath The San Quentin Story is “Drawing Time: 15 Hrs. 42 Min.” While acknowledging the presence of the artist as the reader, they also play on the old saw of one picture and a thousand words: which tells more, and which tells it faster? In its contemplation of this philosophical and aesthetic question, Twins has all the hallmarks of a Conceptual art piece, in this case one that has been run through the wry sensibility of Ed Ruscha, an artist Ruppersberg acknowledges as an influence. The question of the relationship between language (or narrative) and the visual image is set beside the question of the real world, or actual experience: what is the relation of words and pictures to time, in particular to our perceived time?

Allen Ruppersberg, Twins, 1989. Pencil on paper; 2 panels, 24 1/2 x 27 inches each. Collection of Mike Kelley, Los Angeles. Photo: Bruce Morr.

Strangely poignant, The Gift and The Inheritance series and Twins echo both the love of books and the shadow of mortality. But their most intense affects arise in the question of the tie between image and thing. Commingling the categories of scrip, token, contract, and icon, these promissory notes are rendered in the most delicate lines, reminding us of drawing as an activity in time and an object in space. The relations between drawing and writing are foregrounded. What is it to draw a book or to write a contract? What is it to embed a book within an image of its cover and then leave the mystery of its contents to be resolved only after the death of the artist? Neither author nor language is dead in these meditations. All are brought to life in the physicality of the work, and in the presence of reader and writer, artist and visitor, and the living and the dead.

The whole of You and Me or The Art of Give and Take is a dialogue between these precise, pensive pieces and the raucous spectacle in the center of the room. The older works on the nature of image and language seem to have yielded to broader and perhaps more optimistic egalitarianism. If indeed Conceptual art questions the nature of what is understood as art, the corollaries of these questions resonate both within the work itself and within our engagement with it as participants. We viewers are called upon to play with the artist’s materials, an act which resists Sol LeWitt’s declarations about Conceptual art’s execution being a “perfunctory affair.” The reclamation of cultural detritus at the core of Ruppersberg’s work is less invested in questions about the nature of art than the broad capacity of culture to reflect upon our condition today.

Matias Viegener is a writer, artist, and curator who teaches at CalArts and is one of three founding members of the art collective Fallen Fruit.