Matthew Lax, Brunt Drama, 2018. Double-sided digital video installation, sound, 7:30 min. loop, projected on frosted plexiglass, aluminum legs, 48 7/8 × 71 3/8 × 48 in. Installation view, Brunt Drama, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, October 12–November 18, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA). Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Brunt is not the right word. The onomatopoeic brashness of it—guttural, yet oddly refined—like a growl punctuated with a bit of delicate tongue work—belongs in a rhyming dictionary, in an idiom, perhaps in the name of a leather bar (Brunt Daddy)—but not here, in this distinctly virtual space rendered so vast, empty, and dark that a mere glance at its surface infers an echo.

Nevertheless, Brunt Drama is the title of a seven-minute, single-channel figurative animation by Matthew Lax that is projected onto a steel-and-plexiglass sculpture situated as a translucent screen in the center of a darkened room. Indeed, this screen/sculpture mash-up is not the thing one expects to see behind the closed door of a gallery promising a video show, yet its dual purposes are apt. The from-a-distance illusion is that the figures actually move three-dimensionally within the gallery, à la Tupac at Coachella—and the sheer mass of the thing, its distinctly weighty armature, is critical to grounding the otherwise pseudo-sci-fi semi-narrative of the animation’s content, pulling it out of the heady space of code or the invisible logic of frames per second, and dragging it back down to the real and dumb gallery floor.

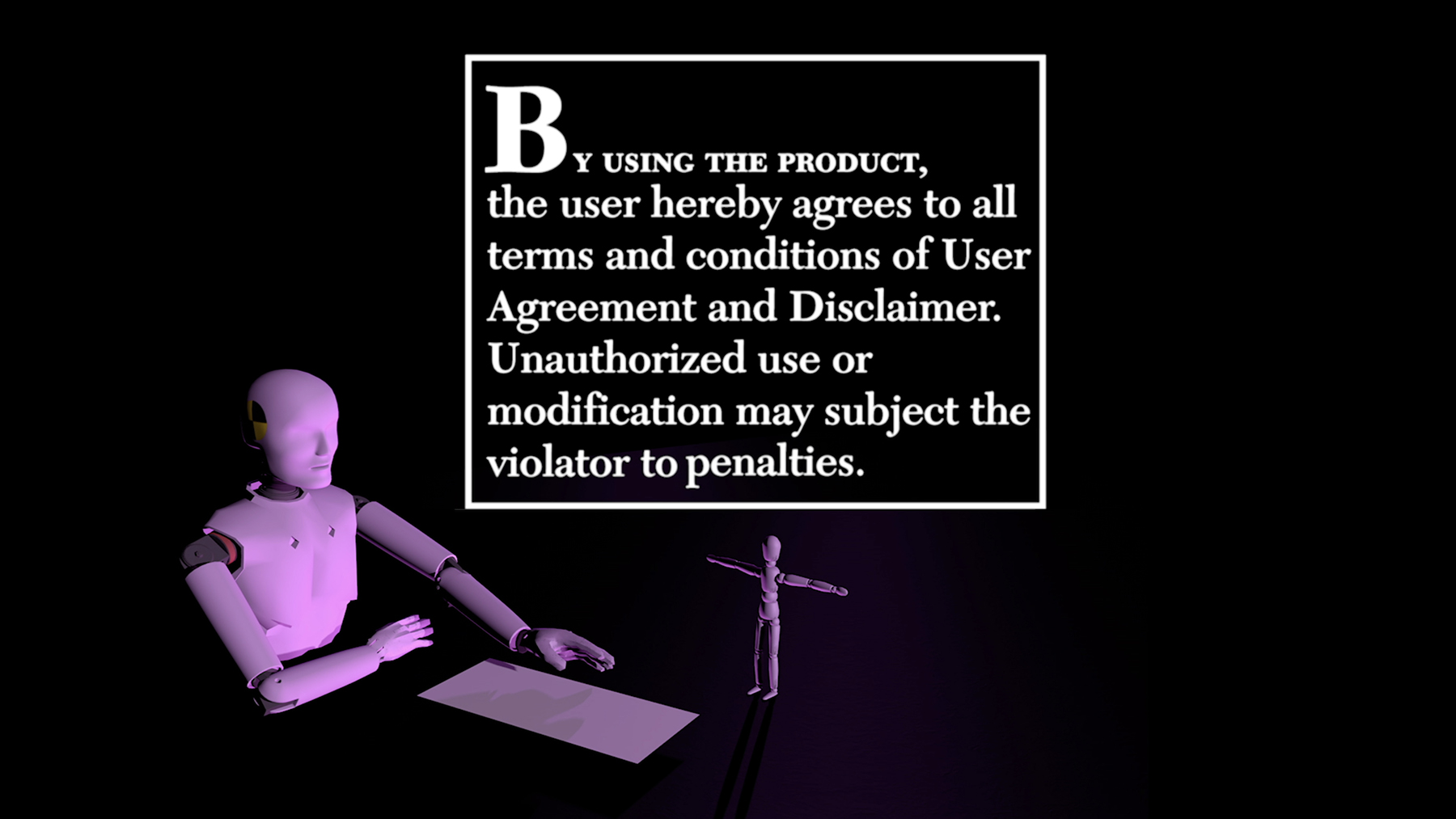

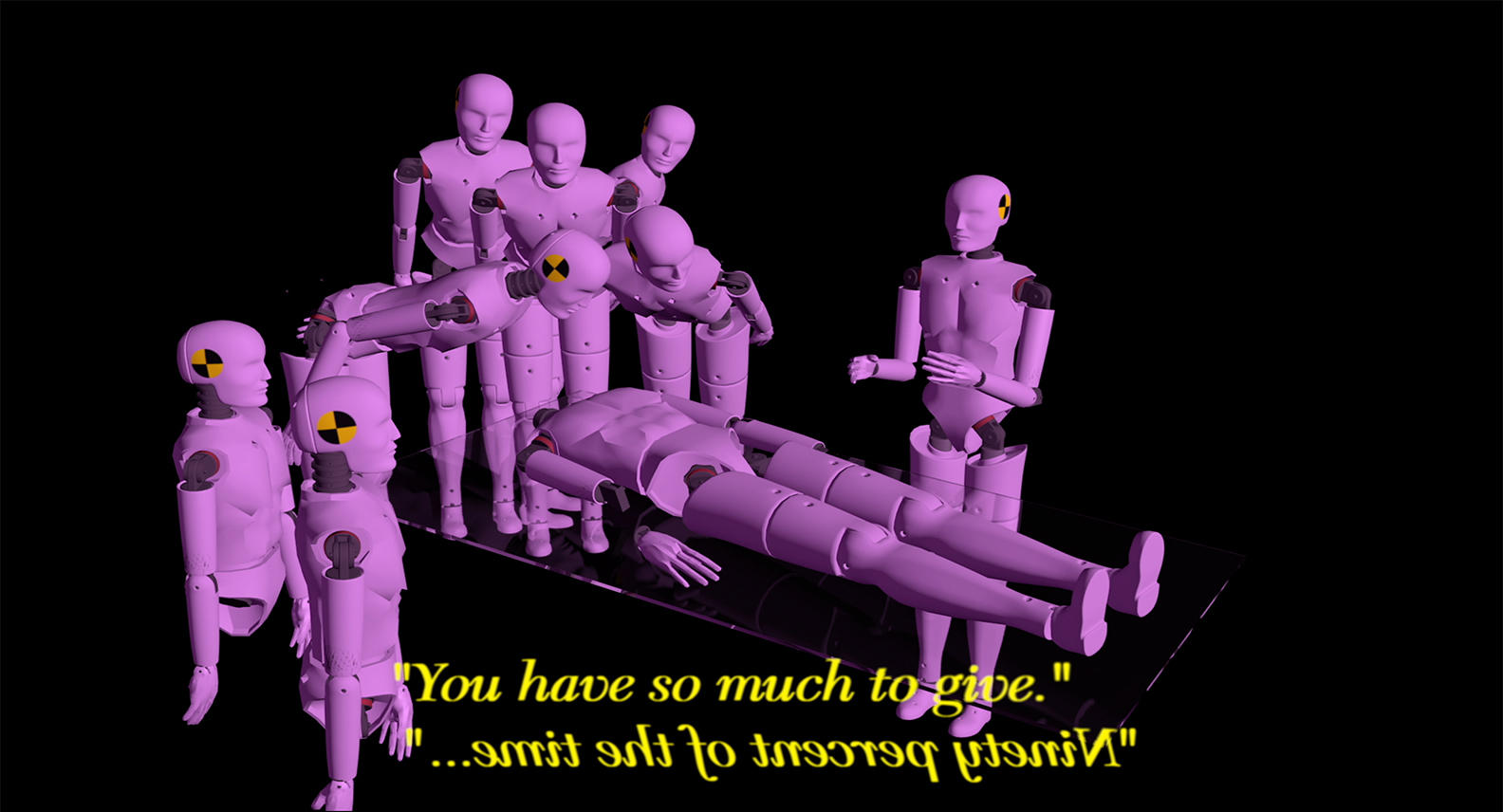

Putting the collapse of literal and conceptual space aside, Brunt Drama is a series of vignettes performed by what may be the last bastion of neutrality in “figuredom”—the crash test dummy. Quite literally representing the body’s potential for abuse and destruction, Lax’s dummies reanimate scene after scene, ranging from the cryptic (disembodied dummy parts tumbling around the screen in a techno-frenzy) to the comedic (one dummy puts its arm around another dummy and says, in subtitles, of course, “you and me, we’re the same”) to the comedic macabre (one dummy puts its arm around another dummy and says, in subtitles, “everything is going to be fine”) to the expert-looking (two opposing rows of dummies pitch a red sphere across their divide, a distinct and perfectly timed “clink” accompanying every catch) to the perfunctory (the dummies fuck, or simulate fucking) to the chaste (a soft-lit dummy spins elegantly, its legs straightened, arms raised, like a Christ on a cross) to the downright satirical (limp-armed dummy looks up at giant floating job description: “Looking for passionate, hardworking team-player, comfortable with gestural imitation and malignant narcissism…”).

On the other side of the screen, we flesh-and-blood dummies are in a harrowing political stretch where cruelty is the name of the game—and one of its many manifestations is a memo leaked in 2018 suggesting that the Trump administration may seek to define gender as an immutable classification assigned at birth based on one’s sex. Yet another harrowing observation of this unfortunately veritable world is that its most powerful person is a gaslighting egomaniac insisting that a three-month-old infant carried thousands of miles on someone’s back to escape violence and poverty is a hardened criminal (the not-so-subtext: they don’t look like us). In an ever-queering and diversifying art world, where identity is the lynchpin of artistic production (and for good reason), what purpose do Lax’s dummies serve? How do we find urgency in an artwork whose central visual themes are same-ness, sexless-ness, aesthetic ubiquity, identity-less-ness?

Something fascinating that emerges in Lax’s installation (or animated video) is the dummies’ position as empathetic beings despite their dummy identity. They are intermediate creatures, performing in a space somewhere between human and machine. Though they are stripped-down avatars, there is something so wrong, so sad about their situation—that they may be trapped in a virtual space where they cannot or will not fulfill their primary role, that is, to be tested, used, analyzed, dumped, and replaced. Of course, this tension embodies that funny/macabre duality that rattles effortlessly throughout Brunt Drama—do the dummies want to play their part? Do they play it well? Do they have a choice? Do we?

While Lax’s use of the medium of animation doesn’t draw too much attention to itself (it’s impressive, but not implausible or avant-garde), it is the fine, fine details that emphasize the dummies as players upon a stage. In one vignette, a sign filling nearly half the screen reads “Applicant must be available, repeatable, and practical for everyday use…” The dummy stands in the virtual foreground and bends backward, as if it were actually looking up and reading the sign, but also as if the sign were so huge and hovering as to be completely overwhelming. The dummy doesn’t just read, it cowers, it is made small. Despite its endless repeatability, it gains individuality through the bend in its body, its admission of smallness. These details bring the role of the dummy to life, allowing Brunt Drama to transcend what could be superficially understood as a software-happy dystopian psychodrama sprinkled with cynical yet comedic relief.

Matthew Lax, Brunt Drama, 2018. Video still. Double-sided digital video with sound, 7:30 min. loop. Courtesy of the artist.

And yet this drama is deliberately unstable. In fact, one never knows if the dummies animate themselves or are directed—in this case animated—in their dramatic roles. It’s a subtle yet consequential difference—the distinction between, say, Walt Disney (a real man who animated fictional characters) and Geppetto (a fictional man who carved a fictional but free-willed boy), or perhaps between Pinocchio (a puppet who self-animated) and Mickey Mouse (an animated character, no more, no less). While Lax explicitly relishes in undermining the human/machine binary, Brunt Drama also undermines the binary between free-willed and pre-determined, opening a space of authorial skepticism within the stage of the dummy ensemble. It is in this skeptical space that the dummies show vulnerability, which in turn earns them something distinctly human: sympathy. Even so, they retain their blankness, their unattributability, which makes them spooky, and of course, uncanny. And lest we question Lax’s skepticism of his own authorial role, remember the vignette where a dummy is seated at a table upon which stands a nearly identical articulated wooden mannequin—you know, the kind an artist might use to draw a figure.

But now for the juicy part: Do machines fuck? There may be nothing weirder and simultaneously more familiar than sex bots—in this case, sex dummies. In Brunt Drama, sex is the compulsory millennial hook—it nods to an art audience whose sex lives frequently, as in almost exclusively, begin and end through data-driven applications. Unlike real sex, where we will eventually have no choice but to method-act our way through an encounter without a script, or improvise through a narrative arc that may never reach a peak or a punchline, virtual spaces demand, and delight in, the necessity that we become avatars. In this sense, the nameless, faceless, penetration-less simulation performed in Brunt Drama seems very close to the experience of partnering via the simulated world—a world which for many of us has collapsed into the real.

Matthew Lax, Brunt Drama, 2018. Double-sided digital video installation, sound, 7:30 min. loop, projected on frosted plexiglass, aluminum legs, 48 7/8 × 71 3/8 × 48 in. Installation view, Brunt Drama, Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, October 12–November 18, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA). Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

As fun and racy as it is to consider sex bots in a critical context, the problem with this simulated sex argument is that it is predicated on the idea that Lax’s dummies represent people when, in fact, the dummies represent machines that represent people. This mind-melding reflexive relationship lends to the complexity of Brunt Drama but also to the sense that the content is just slightly out of reach. Is Lax the puppet master, animating something lifeless to tell a story about the human condition so universal that it might only be understood through an artifice beyond what flesh and blood can perform? Is the question of reality and unreality, authenticity and simulation, even the possibility of pain, sympathy, vulnerability, sex—are all these points silly propositional art-thoughts, considering that animations don’t, well, feel? Has the meaning of animation itself changed because we’ve lost critical distance from the screen—already lost the ability to distinguish the real from the virtual? There is a relationship between cartooning and violence, and also between cartooning and the body. Some of the most infamous cartoons have been fantasy spaces of violence without consequence (think Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner); and while no dummies fall off a cliff into a pile of dust with stars flying all around their heads, there is an implied violence—the dummy will always symbolize imminent violence, the possibility of harm—and yet it must be inflicted by other dummies, right? After all, there’s no one else in the room.

Acting is a word that implies something provisional—the word drama, too, can be a situation or an event. Parts, of course, may be mechanical (a dummy arm, a dummy head) or theatrical roles (no small parts!). Brunt can mean principal force or shock (bear the brunt of), but it can also mean burden. While there isn’t a ton of text in Brunt Drama, it’s certainly a linguist’s paradise—or purgatory, depending on your appreciation of punning. At the forefront of this turn is dummy—which means both mannequin and stupid person. The visual and linguistic distinction between mannequin and dummy lies only within that little round symbol on the side of the dummy’s head. This small but mighty detail takes the subject of Brunt Drama from an unambiguous and perhaps redundant commentary on objectification to a place of violence, intention, simulation. It is an artwork so bent on melding words, sounds, and meanings together—so invested in the potential of the complexity of language combined with artifice—that even a would-be objective description of any of its scenes, as I have offered above, rarely settles into that simple, pleasurable space of skill or making. Drama, too, casts a material ambiguity over what we would normally call a video, or a toon, or even simply “an artwork”—the ghostly, lingering, Shakespearean meta-theater is ever-present in the cavity of Lax’s virtual world, like a net-art version of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. If there is a thought where language and animation meet perfectly in Brunt Drama, it is certainly this: We are the dummies watching the drama of dummies unfold.

Some of Brunt Drama flops, falls flat, casts doubt, crashes, acts out, loses definition, fails to render, misses a beat, chews the scenery. It leaves a distinct feeling of self-consciousness, and, while funny and self-deprecating is a fine thing for art to be, cynicism is overrated. Take, for example, the following text, which appears on one of those hovering dummy billboard/job boards: “No need for close-ups. Plenty of first-person identification; everyone looks the same. The ensemble, preaching to the choir. Incest.” Between absurdity and angst lies confusion. In Lax’s world, everyone (or everything) looks the same, but this is a fantasy world, a fallacy—and the criticism of a perceived homogeneity is a trope. The word incest is especially biting—amoral, of course, but also a criminalized sex act. If incest is meant to demean the art-going audience of a non-profit community-run alternative archive—if we are staged not just as dummies, but as the dummies condoning dummy incest—cynicism might be a generous word in place of some more authentic expletives.

Matthew Lax, Brunt Drama, 2018. Video still. Double-sided digital video with sound, 7:30 min. loop. Courtesy of the artist.

The subtler issue is the trick our socialized brains play on us, and how that plays off the cast of Brunt Drama. When we see blank and sexless, we default: male. Far from neutrality or sameness, the irony is that we land in a world without women, even without gender non-conforming people, all by stripping the figure down to its mannequin parts. Conversely, a “woman dummy” appears in just one vignette, identifiable by its slightly shorter stature—a momentary but uncomfortable heteronormative-leaning associative instant that has no rationale for finding its way into Brunt Drama. That moment aside, it is truly a wonder of the world that patriarchal gender norms can survive even their big moment of mass castration to infiltrate an artwork that was almost certainly not intended to skew man. For Lax, it is a small but profound art tragedy and a hard but unsurprising outcome when disrupting such complex, embedded norms—though Brunt Drama certainly chips away at them.

While gender may not be bending quite far enough to break, Lax is stretching genre, its acoustic and typographic near-twin, just as hard. Consider this: Unlike literature, the dialect of contemporary art has mostly shunned “genre-fication,” in which an artwork is typically identified by its subject, medium, or associated movement—not its message. The artist purist might say this is because art doesn’t narrate—it is beyond language and therefore not subject to the literary terms of textual or time-based media. Lax’s vignettes perform genres that art is never supposed to embrace—mystery, romance, saga, thriller, speculative—one after another. They are all literary genres, of course, but reenacted through the eyes of a filmmaker-turned-animator consciously and specifically situating his work as art. While Lax does a fine job of collapsing the real and the virtual, with his empathetic humanoids and their vaguely referential performances, what’s ultra-fine is the way that Brunt Drama crosses the audience’s interpretive wires, zapping us into absorbing the work through the consciousness of film, literature, and contemporary art—as if we would walk away from Brunt Drama wondering if it was a sculpture, a screen, a tragedy, or all of the above.

And what of the genre of the present? Horror, certainly, but undeniably sci-fi. Nostalgia and futurism may seem like antonyms, but in Brunt Drama, they coexist; the outcome is something that feels (shockingly) real, despite the work’s late 1990s, early-aughts avatar-happy conceit. Remember the climactic scene in The Matrix where our hero, Neo, finally experiences his surroundings not as the world, but as the code of its simulation, able to literally dodge bullets or scale skyscrapers—feats only possibly in digital spaces? It seems that Brunt Drama contains an opposite revelation, an opposite desire: to transcend the façade of digitization and ubiquity, and finally break through to the human side—the side of vulnerability, pleasure, humor, even delusion. And did we do it?

Brunt Drama is a sham narrative and, in a very un-theater-like way, it is a never-ending sham, the looping kind, the kind gifted to us by video, CGI, computers—what you might call technology. If you look back on Brunt Drama to theorize some overarching meaning—argument, character, poetic justice, plot, resolution, truism—you won’t find it. It’s a rabbit hole of an artwork into which we fall, gracelessly, and never hit bottom. If anything, it is a mise en abyme of a mise-en-scène to the nth degree—a nod toward our cynical inclination to mechanize, dumb down, to retreat into digital voids. Yes, contemporary life can feel like one crash test after another, but here’s the last line: Stay human.

Georgia Lassner is an artist and writer in Los Angeles. She is a co-founder of and lead contributor to the art-centric blog unpublished.