The first comprehensive survey of Modern Art by artists of Asian descent in the U.S., Asian/American/Modern: Shifting Currents, 1900-1970, is a groundbreaking exhibition. So why does it feel so old-fashioned? While the show’s mission to redress racist omissions from the Modernist canon is both noble and necessary, its reliance on racial identity amounts to a “separate but equal” approach that seems out of step with a society in which the meaning of race is increasingly in flux.

Indeed, the show seems like a throwback to a more Balkanized era when, with few exceptions, artists of color were visible only in relation to their race. In the culture wars of the late ’80s and ’90s, identity-based exhibitions like The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s (New Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Hispanic Contemporary Art, Studio Museum in Harlem, 1990) and Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art (Asia Society, 1994) were necessary challenges to a mainstream art world that regularly turned a blind eye to the achievements of people of color, women, and queers. Although these shows often reproduced simplistic racial, ethnic, gender or sexual categories, they were (for the most part) a form of what cultural critic Gayatri Spivak has called “strategic essentialism,” or the temporary adoption of a shared identity by a diverse group of people to achieve a common goal.

One of these goals was visibility for under-recognized artists, but the identity politics movement also raised questions about the criteria by which all artists and their work were evaluated. By exposing the chauvinism underlying the art historical record, identity politics sought to reshape the canon, or perhaps even do away with it altogether. Unfortunately, this element of institutional critique often gets lost in current discussions of identity politics, which tend to focus on how “strategic essentialism” became simply “essentialism.” The canon is decidedly more diverse these days, but artists who might once have benefited from identity politics now see it as reductive and limiting.

What is dismaying about Asian/American/Modern is not that it looks at art through the lens of race, but that it seems content to adhere to the dominant assessment of identity politics, abandoning structural critique to become a quiet art historical addendum. Instead of transforming Modern Art history, it merely offers a parallel track. And while it brings many previously neglected artists to light, it simultaneously limits the impact and reach of their work by confining them to an art historical ghetto.

To their credit, curator Mark Dean Johnson and catalog contributor Gordon H. Chang acknowledge the limitations of this strategy. In their introduction to the catalog, they are careful to note that theirs is just one of many possible organizational schemes. They have also smartly included an essay by scholar and curator Karin Higa that questions the exhibition’s premise and warns against the reification and commodification of the category “Asian American.” However, this awareness of the need for greater complexity seems to have had little impact on how the show is organized and presented. The curators assume that the category “Asian American” is an inherently interesting one, and have made little effort to develop a richer, more layered context for the works. Instead, the show’s organization is clunky and uninspired, with wall texts for each piece so copious that one is likely to spend more time reading than looking at the art. To make matters worse, the exhibition design is inexplicably dingy and overcrowded. While the works on view are no doubt historically important, this flawed presentation reinforces rather than dispels their marginality.

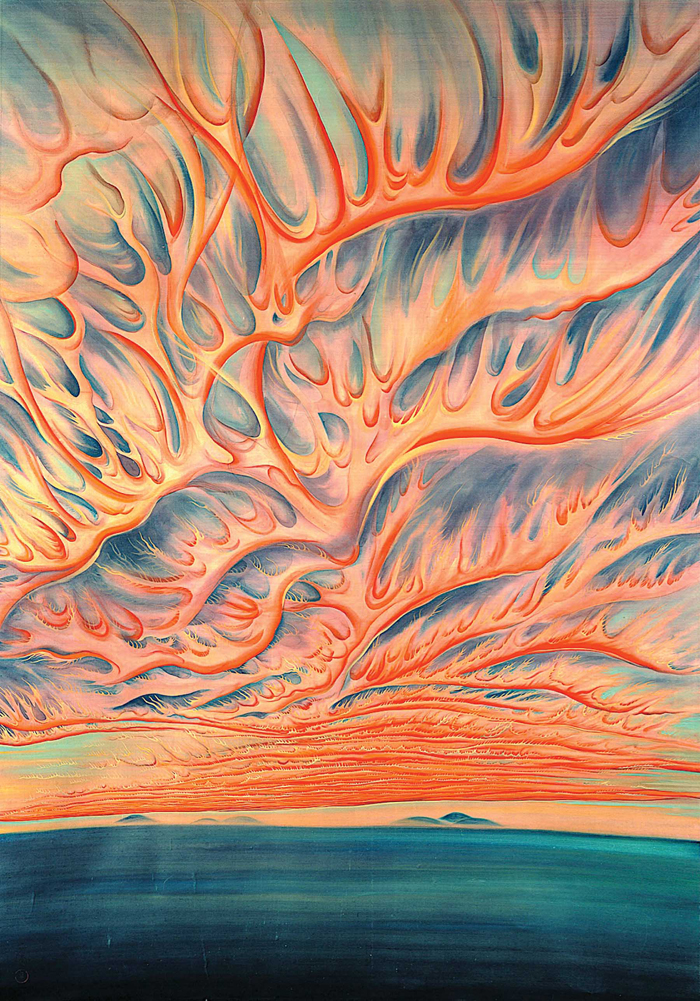

Chiura Obata, Setting Sun: Sacramento Valley, CA. 1925. Hanging scroll: mineral pigments (distemper) and gold on silk, 107 1/2 x 69 in. Courtesy of Gyo Obata.

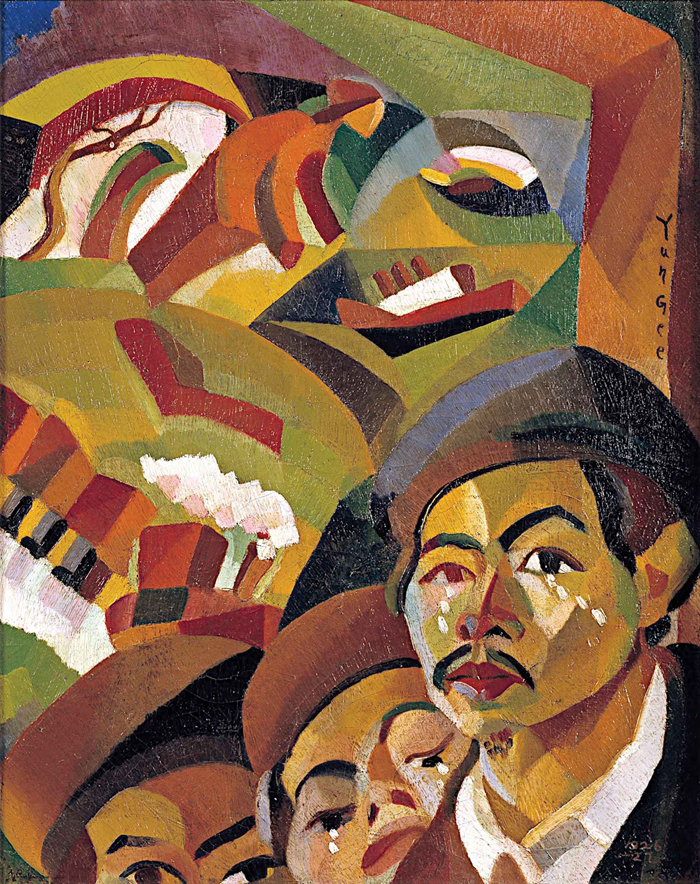

Divided into seven sections, the exhibition starts out as a chronological survey grouped into various themes. The first two—“Looking Both Ways: Asian American Pre-World War II Figurative Hybridity” and “Japanese American Pictorial Photography” successfully frame rarely seen works by early Asian American Modernists within a specific aesthetic and historical context. For example, “looking Both Ways” focuses on how Asian American artists incorporated (with perhaps greater self-consciousness than their non-Asian peers), Modernism’s foundational blend of Eastern and Western influences. While some works look fairly traditional—the bold graphic lines and brushy Japanese calligraphy of Toshio Aoki’s 1900 painting of a Shinto god, for example—there are also some creative experiments in cultural fusion, as well as works that are thoroughly Western. Chiura Obata’s dazzling painting Setting Sun: Sacramento Valley (1925) depicts a California sunset ablaze in a stylized, flame-like pattern lifted from traditional Japanese painting. In Where Is My Mother (1926-1927), Yun Gee captures an immigrant’s wistful sense of displacement in a maze of chunky, Cubist-inspired forms. By contrast, the work of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who in 1948 was the first artist of ethnicity to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, makes no overt reference to Asian motifs or subject matter. His painting Cows in Pasture (1923), with its eccentric organization of space and simplified, geometric forms was inspired by American folk art, although European artists like Fernand Léger and Marc Chagall also come to mind. By presenting this range of approaches and styles within the context of the East/West divide, “looking Both Ways” manages both to stake a claim for Asian American Modern artists and to honor the various ways in which they negotiated cultural difference.

Yun Gee, Where is My Mother, 1926–1927. Oil on canvas. 20 1/8 x 16 in. Estate of Yun Gee, Courtesy of Li-Ian.

By contrast, the following sections—“War and Peace,” “Urban Life and Community” and “Philosophy and Religion”—are impossibly broad and diffuse, shifting the exhibition’s focus towards the ethnographic. Organizing works by subject matter, they risk casting them as illustrations or artifacts of particular historical moments. “War and Peace” includes several images related to the World War II internment of Japanese Americans and a smattering of pieces dealing with the atomic bomb, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War. Other than the fact that Asian Americans made art during or in response to war, it’s not clear what one is supposed to glean from this assortment. And worse, the works end up looking like token representatives in a timeline of wars rather than as multifaceted reflections of the social, political and artistic currents that surrounded them.

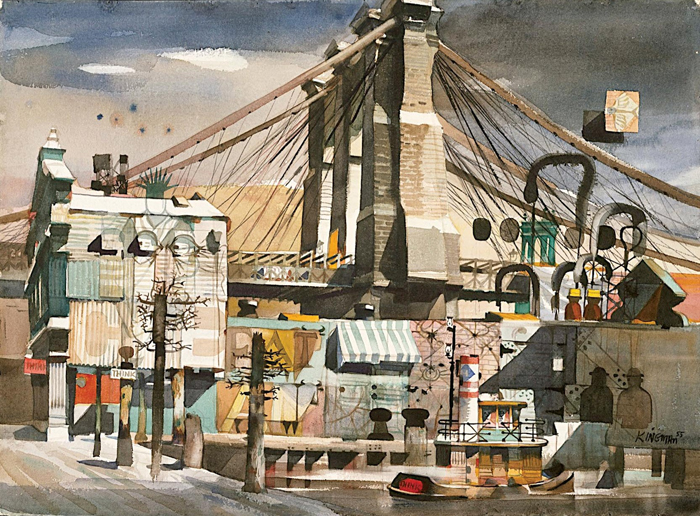

Similarly, the section “Urban Life and Community” contains wildly disparate works with even more tenuous connections. There are intimate scenes of everyday life in Asian American communities: Noboru Foujioka’s loose, Sunday-comics style painting of a neighborhood poker game from 1925, and Irene Poon’s moody 1965 photograph of a family dining in a Chinatown restaurant. But the section also includes works that depict the energy of urban life in general. Dong Kingman’s large T-shaped painting, Urban Fantasy (1954), employs vivid primary colors and bold geometric shapes to depict a shiny city of the future, complete with rooftop rocket ships and high-speed elevated trains. While Kingman’s fanciful work is impressive, it’s not clear what rocket ships have to do with poker games, and the section seems divided between two impulses—one intimate and documentary, the other grand and visionary. Save for their Asian American creators, there would be little reason to group these works together. The decision to do so is not only a disservice to the artists, it’s also a missed opportunity to look more closely at the role of Modernist aesthetics in the representation of ethnic communities.

The exhibition then takes a strange turn when it reaches the ’50s and ’60s, with a section titled “Nature and Sexuality as Abstraction,” which seems like a desperate attempt to impose subject matter on abstract works. The featured artists—Ruth Asawa, Masami Teraoka, Yayoi Kusama among them—were undoubtedly inspired by nature and sex (who isn’t?), but they were also engaged with the aesthetic and formal ideas of Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Asian iconographic and design traditions. Asawa, whose organic, hanging wire sculptures play with the boundary between interior and exterior, mass and transparency, studied with Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in the ‘40s, where Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage were among her classmates. Similarly, painter Leo Valledor was a founding member of the Park Place Group in New York, which emphasized hard-edged, geometric abstraction. Although the wall captions often fill in this background, the rubric of “nature and sexuality” inaccurately suggests that these artists represented a subset distinct from the mainstream of American abstraction.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Self Portrait as a Photographer; 1924. Oil on canvas. 51.8 x 76.8 cm. Lent by Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982.

The final section, “Ink and line,” feels like a different exhibition altogether. It is neither chronological nor based on common subject matter; it is also the most satisfying part of the show, precisely because it applies a clear thesis to a wide range of work. Exploring how Asian American artists have interpreted the East Asian tradition of ink drawing, it juxtaposes paintings from different time periods in relation to this much older artistic heritage. While there are fairly traditional examples from as late as the ‘30s, there are also more adventurous pieces like C.C. Wang’s Landscape (1969), an image of a rocky mountainside that refers to both older Chinese landscapes and Abstract Expressionism. Mounted on a traditional scroll, it makes a fascinating companion to Martin Wong’s Fairy Tale (1967), a long, thin strip of paper packed with energetic graffiti style writing. Wong’s conflation of graffiti, calligraphy and the scroll format finds unexpected resonances between modern-day street culture and ancient artistic traditions. “Ink and line” brings forth a series of such tensions—abstraction vs. representation, oil paint vs. ink, gestural drawing vs. calligraphy—that are integral to both traditional Asian art and Modernist discourse.

Indeed, what’s missing in large part from Asian/American/Modern is the third term in the title. not only does the majority of the show privilege ethnography over aesthetics, it simply doesn’t look like an exhibition of Modern Art. To begin with, most of the walls are painted gray. This may seem like a minor quibble, but the standard for exhibitions of mid-century Modern Art—canonical Modern Art—is a spacious room with pristine white walls, like the adjoining exhibition of Maya Lin’s limpid sculptures or the Modern galleries of the de Young’s permanent collection upstairs. By contrast, the Asian/American/Modern rooms feel close and musty. Perhaps the color is intended to challenge the convention of the white box; however, it inadvertently conjures other associations, such as the darkened rooms where ancient artifacts are often displayed.

Dong Kingman, South Street Bridge; 1955. Watercolor on paper. 21 1/2 x 29 3/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, George A. Hearn Fund, 1955.

This impression is reinforced by an overcrowded, Wunderkammer-style installation. Works are hung so close together that it’s difficult to focus on one piece without being distracted by its neighbors, an effect that is exacerbated by long captions accompanying each work. The result is an overwhelming amount of information and very little space to process it. In a particularly egregious case, Kingman’s Urban Fantasy is hung directly above a smaller, much paler image by Chen Chi. Although both works are cityscapes created in the ‘50s, they are otherwise unrelated. Their salon-style arrangement makes Chen’s image look like an afterthought and detracts from the appreciation of both paintings.

Thus Asian/American/Modern ends up looking more like an illustrated history lesson than an exhibition of Modern Art. Yet, perhaps its multiple failures are simply signs of the difficulty of the task at hand. How much nuance can one expect from a show that spans the better part of a century, presents only one or two works from each of over 70 mostly unknown artists, lumps together four different ethnicities (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino and Korean), and attempts to trace the currents of Modernism? It’s perhaps too much to ask of one exhibition, especially one as timid as Asian/American/Modern.

And yet, there’s a lesson to be learned from its ambition: Whether it intends to or not, Asian/American/Modern exceeds its own attempts to categorize and contain, exposing the ways in which traditional racial definitions are increasingly inadequate. If we are to continue to talk about art and race—which of course we must, since the “post-racial” future is a long way off—let’s talk about it in a way that respects complexity and contradiction rather than falling back on familiar assumptions. The best parts of Asian/American/Modern achieve a synergy of subject matter, aesthetics and history that goes beyond simply planting an Asian American flag on the art historical map. Let’s hope they are the seeds of a discussion that continues to bring racial difference into a common matrix of experience rather than shunting it off to its own little silo.

Sharon Mizota is a writer and critic based in Los Angeles.