Originally founded in 1995, the SITE Santa Fe Biennial was for many years one of the world’s few international biennials, and its exhibitions were highly celebrated. There are now over 150 significant biennial or triennials worldwide, and the repercussions of the increasingly globalized and hyper-financialized art world have led to a so-called biennial effect, where a small number of international artists and curators descend on exhibition contexts the world over to temporarily display their brand of work without a deeper connection to the place or local community, and then move on to the next opportunity.

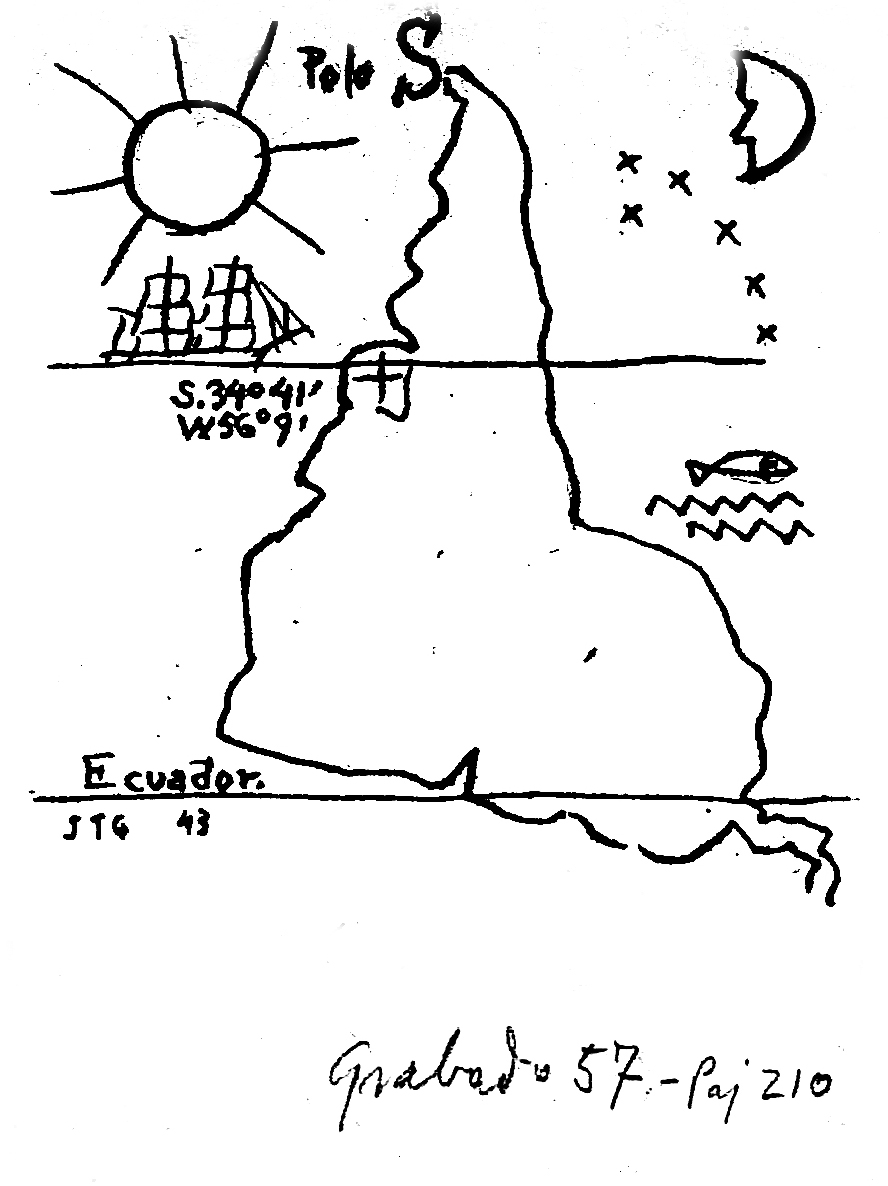

In 2010, when Irene Hofmann was appointed director of SITE Santa Fe, she responded to this prevalent biennial culture by inviting SITE curator Janet Dees and a team of international curators to reimagine the Biennial and launch a critical analysis of the format itself. The result of this exercise is SITE’s new biennial series SITElines: New Perspectives on Art of the Americas, which limited the scope of the biennial to the region from “Nunavut to Tierra del Fuego.” The curators claim that the history of Santa Fe itself is essential to this reorganization. “[The region is] a rich microcosm of the Americas: before statehood, New Mexico was first and remains in part Native American land, and then, successively, a Spanish kingdom, a Mexican province, and an American territory. With SITElines, we link this fertile territory to the rest of the Western hemisphere, moving from an east–west axis to one that runs south–north.”1 This south–north reversal is reminiscent of América Invertida, a 1943 drawing by Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García, in which he represented a map of Latin America with the Polo Sur (South Pole) at the top, the privileged “north” turned on its head.

Joaquin Torres Garcia. America Invertida, 1943. © Museo Torres Garcia. www.torresgarcia.org.uy

Geography is the first organizing principle of the inaugural SITElines, called Unsettled Landscapes. All the works selected by Hofman and the curatorial team touch on land, whether literally representing it or taking on more conceptual approaches related to territory, history, displacement, environment, or commerce. Santa Fe, a place where many locals distinguish their roots as Hispanic or Latino (the former to Spain, the latter to Latin America), is a particularly complex vantage point not just to rethink “south–north” but also the issue of who has settled – or in this case, unsettled – the landscape. The 40 artists in Unsettled Landscapes come from 15 countries and utilize a diverse set of approaches to reveal and challenge norms of seeing the land under their own feet, as well as who exercises power over it.

SITE Santa Fe is located in a light-industrial neighborhood of Santa Fe, not too far from railroad tracks and what has become an interior design and gallery neighborhood, adjacent to but still in walking distance from the historical and tourist district (where Native American artifacts are sold alongside kitschy reproductions made in China). SITE Santa Fe’s facade on Paseo de Peralta is punctured by a groovy white portal, commissioned from the architect Greg Lynn, an invitation to visitors to be transported away from both Santa Fe and any expectations about contemporary art they might have arrived with. Inside, SITE is a conventional white exhibition box.

The first artwork encountered in Unsettled Landscapes is the installation Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut (2013) by U.S. artist Andrea Bowers. What initially appears to be a large green macramé sculpture with acid green ropes dangling with small pieces of branches and bark knots at each endin fact, the remnants of an environmental action Bowers participated in in Arcadia, California, in 2012: a sit-in to preserve an old-growth oak and sycamore forest. Bowers was imprisoned for her activism and, ultimately, the trees were razed. Thus the documentation of the protest and Bowers’s installation are all that remain of the forest. Further inside the exhibition is a thematically related video installation, The United States vs. Tim DeChristopher (2010). In it, Bowers shares the saga of DeChristopher, a young environmental activist who bid on a tract of Federal land in Utah in 2009—with no intention or ability to pay for it—in order to preserve it from being developed. After winning the auction and then defaulting on his bid, DeChristopher was imprisoned for two years for making false statements under oath. Memorial and The United States vs. Tim DeChristopher invite viewers to contemplate the destruction of the environment and to think about the role they, along with activists and artists, can play in preservation.

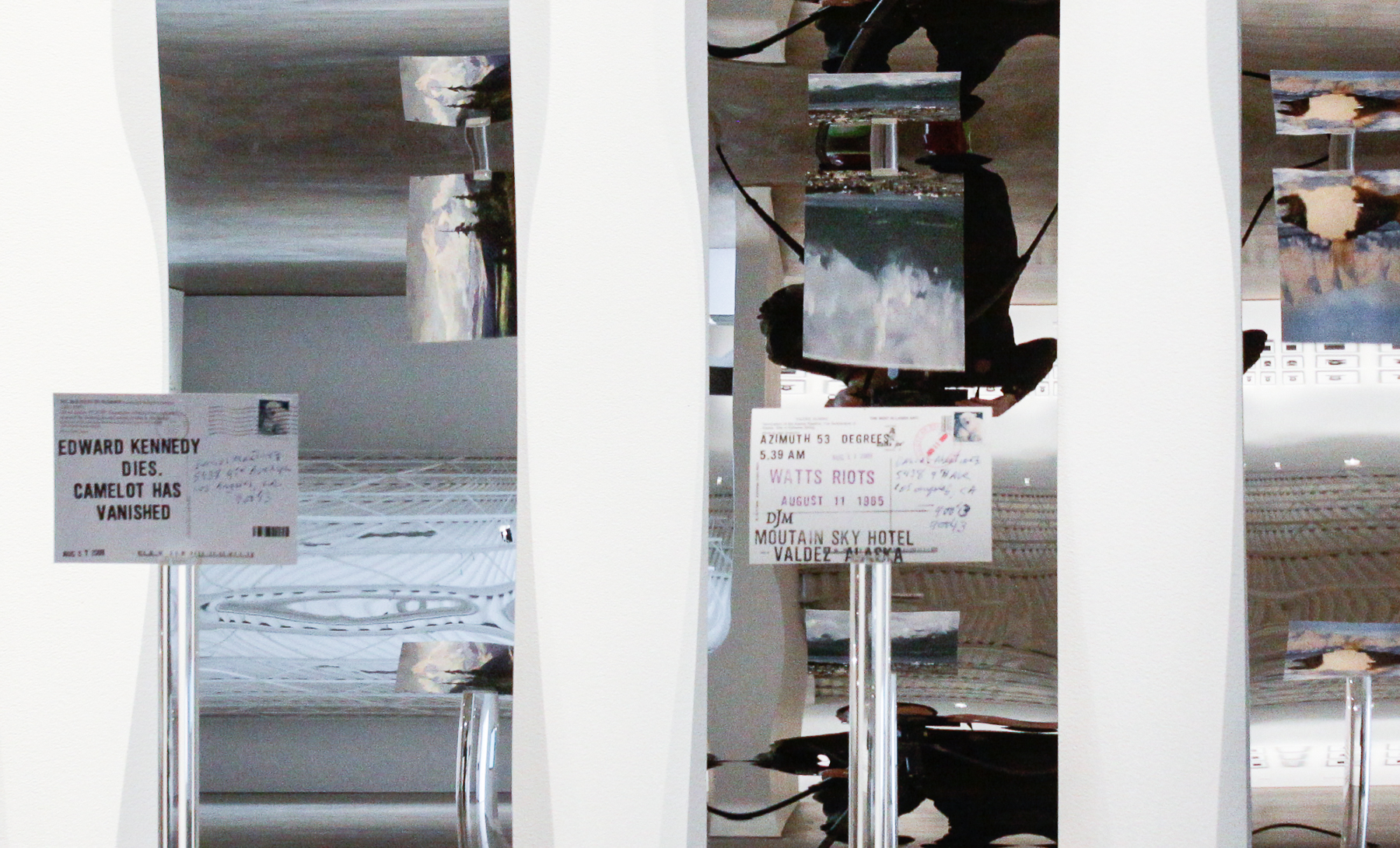

Daniel Joseph Martinez, installation and detail view of She could See Russia from Her House, Those who wish for peace should prepare for war! —Old Sasquatch Proverb (In search of the Tribe Called Sasquatch, or who really built the Alaskan Oil Pipeline) 16 Communiqués and found photographs from traveling the length and breath of Alaska during the month of August, 2009”, 2010 . 16 postcards, mirrors and plexi rods, 6.5 x 30 x 5 feet. Courtesy of the artist.

In the first large gallery space, Los Angeles artist Daniel Joseph Martinez takes the viewer’s complicity one step further. In She could See Russia from Her House, Those who wish for peace should prepare for war! – Old Sasquatch Proverb (in search of the Tribe Called Sasquatch, or who really built the Alaskan Oil Pipeline) 16 Communiques and found photographs from traveling the length and breadth of Alaska during the month of August, 2009 (2010), Martinez presents a series of postcards reflected in funhouse mirrors along the wall. Each postcard demarcates sites Martinez visited across Alaska to map landscapes scarred by the development of the Valdez–Deadhorse oil pipeline. One can only view the touristic images on the postcards through their reflection in the mirrors, where one’s own body is distorted too, as though the humor in the present moment is linked inextricably to the environmental degradation that results from the search for and extraction and transportation of fossil fuel. Across the room, Colombian Miler Lagos’s The Great Tree (2014) stretches its trunk from floor to ceiling. It isn’t until the viewer approaches Lagos’s Tree that one can see the striations in the material it is built up from: stacks of newspapers (the local New Mexican), cut and burned back into a tree trunk form. Diametrically across the room hangs Perimetros (Ceiba)/Perimeters (Ceiba) (2014), Johanna Calle’s drawing of a large ceiba tree. The tree is rendered in outline with typewritten text on old blank notary sheets used to register land ownership in Calle’s native Colombia, where ceibas often mark agricultural property lines. The texts themselves are culled from newspaper articles about land reform. The playful and inviting qualities of the works in the first gallery—Martinez’s funhouse mirrors, Calle’s giant tree, and a miniature coin-minting factory by Antonio Vega Macotella—draw in the viewer. But inspecting the works more closely and reading the wall didactics reveals that the subject is a sobering one—the destructive effects of global industry on the environment and the viewer’s participation in this system through our consumption of goods, including artworks.

Cutting and pasting, or collage, is a thread that connects many of the works in the exhibition. In the transitional hallway spaces, we find the photographs of Edward Poitras, a Canadian artist whose Offensive/Defensive documents an intervention performed in 1988, in which he cut a strip of sod from his home in the George Gordon First Nation and exchanged it with a similar strip at the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon. With this graft, the artist represents himself as an autochthonous subject, both literally (autochthon is Greek for “from the land”) and symbolically, as a historically oppressed minority whose work is rarely exhibited within museum walls. Nearby, Los Angeles-based, Brazilian-born Clarissa Tossin’s When Two Places Look Alike (2012) compares Fordlandia, in Brazil, where in 1928 Henry Ford constructed a model American town in order to expedite the harvesting of rubber for tire production, and Alberta, Michigan, where Ford built an almost exact replica of the Brazilian company town in 1935. In a series of photographs, Tossin juxtaposes the same house designs situated in wildly differing environments and climates. In one of the photographs, set in Fordlandia, the artist’s hand holds up a picture of Alberta. While the buildings map perfectly onto one another, the landscapes around them signify dramatically different places. The buildings represent the force of Ford’s views imposed on two different contexts. Fordlandia eventually failed because Ford’s “one size fits all” vision for mass-production didn’t take into consideration the cultural, social and environmental context of working in the Amazon jungle.2

Clarissa Tossin, When two places look alike, 2012. Digital photographs, 27 x 40 inches each. Courtesy the artist.

In the back gallery, the concept of exchange between artist and local community is more straightforward. Juan Downey’s Video Trans Americas (1973–76) fills the space with TV monitors showing films he made traveling throughout the Americas, from Mexico to Chile, recording interviews with members of different indigenous cultures. At the time of their creation, Downey showed each community its own videos, as well as sharing them with the next communities he visited. The Chilean artist saw himself as a “cultural communicant, an activating aesthetic anthropologist with a visual means of expression: video tape.”3 A viewer today might have a different understanding of the ethics of social practice in art and therefore might be critical of the kind of exchange that Downey proposes. But in the 1970s, when the work was made, video technology held out the possibility of equality and a kind of liberation through a more democratic time-based medium.

Nearby, two installations by Mexico-born and New York-based artist Pablo Helguera exhibit a more contemporary approach to social engagement. The first appears to be a replica of a small historical society, replete with crown molding, walls decorated with framed documents, and glass vitrines filled with ephemera. Most of the artifacts are real, borrowed from local Santa Fe museums, and they cover a period of New Mexican history dating back to Pancho Villa’s visits to the Mexican-American War in the nineteenth century. Helguera’s second installation resembles a gambling den in a bordello. In his use of evidentiary objects and fictive spaces, Helguera’s installation communicates a critical approach to history and artifacts—asking who has the right to tell these stories and why? He also engages his audience through a series of performances that were scheduled throughout the run of the biennial. Helguera is director of adult education at the Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, and has been invited by SITE Santa Fe to continue his research into local historical archives and present his findings at the SITElines biennial in 2016.

Liz Cohen , Rio Grande, 2012. Chromogenic print, 50 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

Across the gallery, Liz Cohen investigates the tropes of popular car culture with her mashed-up low-riding car, Trabantimino, part East German Trabant and part Chevrolet El Camino. The United States-born artist undertook the project to transform the car and record it as both its mechanic and its car model in 2002, after bringing the Trabant back from Berlin. Blurring the lines between commentator and participant, Cohen won the Compact Radical category at Espanola’s annual low-rider festival in 2013. In Unsettled Landscapes, Cohen’s photographs of the Trabantimino in various New Mexican landscapes are familiar in their tropes—a gorgeous car in a landscape with a beautiful model—yet they upend expectations of who is in front of the lens, behind the lens, and under the hood.

Spectatorship and who controls point of view is very much the project of Los Angeles-based, Mexico City-born Yishai Jusidman, whose painted spheres of panoramic outdoor vistas from the Astronomer series (1987–90) dominate the next room of Unsettled Landscapes. In order to see the landscape here the viewer must walk around it. Wall didactics reveal that the works are inspired by such venerable painters as José María Velasco and John Constable. Jusidman’s paintings create an intimate viewing experience yet frustrate the viewer’s desire to achieve an understanding of the whole. This same sense of delayed comprehension is found in the large-scale paintings of the Amsterdam-based, Argentina-born Irene Kopelman. Her 50 metros de distancia o más B/50 Meters in Distance or More B (2010) first appear to be pale-hued abstractions but are in fact depictions of ice and reflected light that Kopelman perceived while on a boat expedition to Antarctica, where she accompanied a scientific expedition. These paintings explore not only the possibility of exchange and collaboration between artists and scientists, but also the importance of the artist as witness to the effects of climate change.

Kent Monkman , installation view of Bête Noir, 2014. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Sargent’s Daughters Gallery, New York. Photo: Eric Swanson.

Some of the most humorous and cutting work of the biennial is found in small rooms adjacent to the main rear galleries. One contains a mesmerizing video Fordlandia (2014) by Melanie Smith, who was born in England and lives in Mexico City. Smith made the video in the same location as Tossin’s photographs, and her slow shots capture the wildlife and verdure that have engulfed Ford’s utopian vision. Houses and factory buildings are shown overgrown by vines and home to alligators and frogs. In showing us how the natural world takes over an environment that has been abandoned by humans, Smith asks us to think about the very condition of human dominion. Next door is Canadian artist Kent Monkman’s witty installation Bête Noire (2014). A Native American figure in full feather headdress, shirtless (with a dream-catcher at each breast like a bikini top) and in chaps, rides a motorcycle through a diorama of the Western plains. Against a painted backdrop of purple mountains, the rider encounters a giant, flat Cubist buffalo lying on the ground in front of him, slain by arrows. This knowing mish-mash of cultural codes includes satire, homoeroticism, patriotism, and tropes of modern art and anthropological museum display.

Minerva Cuevas, Seascape, 2012. From the series Hidrocaraburos. Oil on compressed wood board covered in chapopote (tar); 40 1/8 x 36 3/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City. Photo: Estudio Michel Zabé.

Most of the works in the last two galleries are archival or refer to other works that are documentary in their process. Thick black tar hangs down like unguent stalactites from Mexican artist Minerva Cuevas’s small seascape oil painting Hidrocarburos (Hydrocarbons) (2014). This work (commissioned for Unsettled Landscapes) is part of Serie Hidrocarburos, which Cuevas presented at Kurimanzutto gallery in Mexico City in 2007. Serie Hidrocarburos is a large-scale installation of artifacts and drawings all dipped in tar as part of Cuevas’s research on the hazards of the Mexican oil industry. Nearby, in Amanaplanacanalpanama (1995), Luis Camintzer, a German-born Uruguayan artist who resides in the United States, presents a series of brass plaques into which have been etched mostly European historical records about Panama and the creation of the canal. The texts bear the colonial stamp of their origin, for example: “Probably no class of mankind are more perfectly satisfied with themselves, and contented in their situation, than the native inhabitants of this country.” Across the room, Agnes Denes’s 1982 project Wheatfield—A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan is chronicled in a series of photographs of the planting, growth, and harvesting of two acres of wheat on a landfill in view of the twin towers. The images are striking in the contrasts they present—encompassing a red harvester, golden wheat, blue sky, and the Manhattan skyline. An early pioneer of land art, the Hungarian-born American artist sought to provoke a conversation about land usage, hunger, and the banking system. While Downey, Helguera, and Cohen each sought, in unique ways, to engage and exchange ideas with communities through their art as participants, the works of Cuevas, Camintzer, and Denes position the artists as outsiders, critically assessing the position of the dominant culture in relation to the land and its inhabitants.

Agnes Denes, selected documentation from Wheatfield–A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan–With Statue of Liberty Across the Hudson, 1982. Courtesy of the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects. Photo: Agnes Denes and John McGrail.

What emerges from this selection of works is an overarching theme of landscape as perceived by artists from very different backgrounds, cultures, and eras who use disparate materials and practices to create works intended for distinct environments. In the catalog, essayist Lucy Lippard hints at this: “The artists here share modernity, but are nurtured by some very dissimilar cultures. Local ecosystems and topography can be equally influential. The bare bones of New Mexico bear little resemblance to the lush tropics of Suriname or the frozen expanses of Cape Dorset.”4 At first I too asked myself how to consider and compare the wide variety of work featured in Unsettled Landscapes, from a North American’s historical work in social practice to a contemporary South American’s paintings of the Antarctic? (And further, what are their relationships to Santa Fe, New Mexico?) Landscape, as a curatorial taxonomy, seems to have been chosen as a provocation to shatter what Michel Foucault calls “all the familiar landmarks of thought—our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography—breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old definitions between the Same and the Other.”5

Two of the curators on the Unsettled Landscapes team, Candice Hopkins (a member of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation) and Lucia Sanroman (a independent curator, formerly of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego) offer up a definition of the word landscape: “Our question is not what is landscape, but rather, how is landscape used to support particular social values, values that prioritize certain kinds of experiences and forms of knowledge over others? In other words, how does landscape function as a device or a social apparatus?”6 Substituting the word biennial for the word landscape, as Hofmann and Dees do in their essay in the exhibition catalog, you get to the core questions of the exhibition: How is a biennial used to support particular social values, values that prioritize certain kinds of experiences and forms of knowledge over others? How does a biennial function as a device or a social apparatus? In seeking to upend the model of the “Eminent Biennial Curator” of past iterations of the SITE Santa Fe Biennial (Francesco Bonami, Rosa Martínez, Dave Hickey, and Robert Storr have all curated biennials there), SITElines: Unsettled Landscapes does present a more problematized exhibition with a broad selection of diverse voices, as emblematized both by the curatorial team, the diversity of the artists selected, and the focus on the environment. But can one undo the logic of biennial culture through a biennial?

Two more biennials in the SITElines: New Perspectives on Art of the Americas series are coming up, in 2016 and 2018. The curatorial team for SITElines 2016 has recently been announced, with Rocío Aranda-Alvarado, Kathleen Ash-Milby, Pip Day, Pablo León de la Barra, and Kiki Mazzucchelli assembled under the leadership of Hofmann and Dees. The theme of the next SITElines biennial will be announced alongside the artists selected in February 2016, with the exhibition opening in July 2016.7 If the 2016 collective curatorial team continues the work begun in the current iteration, then SITE Santa Fe will be in the position to advance the conversation about how gender, racial, ethnic, and economic norms are addressed in a biennial culture and demonstrate the complex, hybrid, and heterogeneous state of art today.

Alexandra Grant is a Los Angeles-based artist who uses language, literature, and exchanges with writers as the basis for her work in painting, drawing, and sculpture. Grant’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Los Angeles and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LAMCA), among other museums and galleries.