Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010), which makes its American debut at Paula Cooper, is big.1 Not materially or spatially big, The Clock is a film composed of thousands of snippets from other films, all referencing time in some way. The staggering thing about this big piece is that it functions as a twenty-four hour clock. Whatever moment you step into the screening, you see or hear the current time, and the film tracks real time through the entire twenty-four hours of its loop. If you enter at 6 p.m., and leave at 2 a.m., you will have watched the passage of every minute of those eight hours, which is an extraordinary experience in the context of a medium that usually magically folds or stretches our perception of time. The audacious subject of The Clock is time itself, certainly a huge topic, perhaps the biggest of all.

As a very lengthy film, The Clock is in the company of iconic works such as Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964), Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985), and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler: A Film (1978). These films dazzle you with their demands and eat your life. While seeming to be about one thing, they are also about everything. Whether the source material is as minimal as an eight-hour shot of a skyscraper (as in Empire) or as excruciating as the minutiae of the Holocaust (Hitler), the viewer leaves with an excess of thoughts, exhausted and exhilarated at the same time. Marclay’s material is unrelenting but also surprising, as we come to see how references to time infiltrate both ordinary life and exceptional moments. The Clock shimmers with technophilia. Rather than the printing press, the photographic image, or film, we see that the clock is the technology that most defines the condition of modernity.

Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010. Single-channel video, 24 hours. Photo: Todd White Photography. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and White Cube, London.

As a clock face approaches six o’clock, the hinge of the film’s repeated looping, we see the superimposed credits of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). Marclay appropriates Chaplin’s foreword to explain the film’s theme: “Modern Times: A story of industry, of individual enterprise—humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” This is only one of many scenes in factories and offices, reminders of how lives are at every moment regimented and meted out. Labor intrudes at many junctures of The Clock, and the technology of timekeeping is underscored by the technology of cinema itself. Every piece of time can carry a symbolic resonance: 8 a.m., noon, 5 p.m., or midnight; think of 11:11, 4:56 or 9:11. The Clock testifies to the Taylorization of modern life, the Fletcherization of every bit of our existence. Paul Virilio reminds us, “At the close of our century, the time of the finite world is coming to an end; we live in the beginnings of a paradoxical miniaturization of action, which others prefer to baptize automation.”2 While addressing speed and politics, like many twentieth century philosophers, Virilio also examines the fundamentally technological nature of modernity. The technology most visibly at hand here is that of time. The inventions of the industrial revolution changed our sense of space: suddenly Paris was a five-hour train ride or forty-minute flight instead of a three-day horse ride. The telephone vastly accelerated this, as we could speak to people across the world without being there. Modern art often deals with these shifts of space and time, but after modernism time stubbornly remains unconquerable. The telephone appears nearly as often as the clock in Marclay’s piece, almost as a reminder that though distance might be manageable, no one is time’s master.

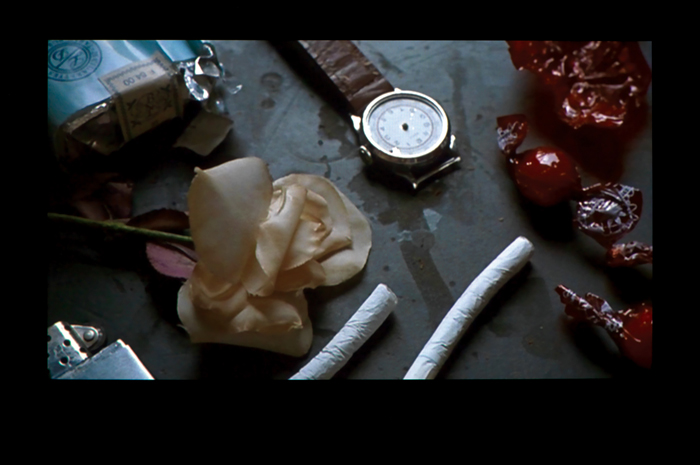

Christian Marclay, still from The Clock, 2010. Single-channel video, 24 hours. Photo: Todd White Photography. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and White Cube, London.

Cinema is the dream of capturing the movement of time, and artists have been drawn to film since its invention. The enchantment began with theatrical ideas of verisimilitude (the play should take place in a unity of time, place, and action), then moved through narrative realism to an experiential realism. Marclay’s Clock is a masterwork of editing, with beautiful cuts and careful sound edits that often overlap the visual ones. Most of the film segments that make up The Clock are quite short, just long enough to give context to the clock or the watch included in the scene, and then the film quickly cuts to the next. You recognize a scene or actor here or there, but after a time of guessing games you settle into the hypnotic spell. The smoothness of the edits contributes to this mesmerizing effect. They draw the viewer in to a world composed of time. The resulting filmic collage moves into myth, metaphysics, and monumentality. Faced with this excess of images, this surfeit of edited information, the viewer is at sea with time while at every moment knowing exactly what time it actually is. We are overcome by speed.

Many of the excerpts come from little-seen or obscure films, many in languages other than English. Time is a global experience after all. At first you see a rush of planes and trains, schedules and timers, people missing buses or catching boats. There are meals, eating time, domestic time, sleep time and even dreamtime. People hurry down streets, rush to work, coming, going, arriving, departing, always on their way somewhere except for the times they are not, and then they are waiting. Time stands still, hours melt while nothing happens but the passage of time—the characters wait for a call, an arrival, a sign, a message. Marclay’s viewer is paralyzed by time’s spell much as the characters in the film clips. One of the experiences of the film is the inside/outside nature of the time being told. Here time is literalized to the real time of our experience watching, both anchoring us outside the narrative and anchoring our narrative inside the film. We come to see time as the regime that structures everything, from our viewing experience to the executions of convicts, the time of birth and the time of death. Time becomes ordinary and extraordinary at the same instant. At a quarter past three, Pip arrives at Mrs. Havisham’s mansion, filled with great expectations.

While watching The Clock, I couldn’t stop to make notes or else I’d miss what was happening. It’s an analogue for the experience of time: grab any part of it and you miss something else. The screening room at Paula Cooper was tricked out with velvet curtains and plush sofas in a way that conflated movie theaters and living rooms, public space and private. People stretched out, some sleeping, couples with their limbs entwined, a beer can on the floor and food wrappers visible in the corners. The Clock in this incarnation is essentially a social experience, similar to every visit to the cinema except in its subject, which while seeming to be about time is also simultaneously about the nature of film itself. Look at it closely and there’s a strangely compelling disunity, an opening into infinity. It’s always midnight somewhere, and always noon somewhere else. Or look away. But though we may ignore time, it does not ignore us. And Marclay’s film makes sure we know it.

Christian Marclay, still from The Clock, 2010. Installation view. Single-channel video, 24 hours. Photo: Todd White Photography. © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and White Cube, London.

The Clock is in league with an earlier generation of Conceptual artworks in which time is a subject. Tehching Hsieh’s durational performances of thirty years ago often unfolded over the span of a year, during which time he variously locked himself in a cage, lived outside, or famously punched a time clock every hour on the hour. He describes these as explorations of time and struggle rather than endurance, but they also serve as an index of duration—the passage of the year—much in the manner The Clock indexes a twenty-four hour day. On Kawara’s ongoing series of date paintings inscribe the day’s date on one canvas after another, changing a bit in color and font, but essentially marking the passage of time using the local conventions of the country in which the paintings are made. Thus the paintings also become an index of space. Marclay’s film benefits from being seen in light of these precedents, since all of these works touch on place yet privilege the regime of time. Place is marked in The Clock by visual referents, glimpses of monuments and familiar foreign and domestic locations, but they fall away against the monumentality of time.

In several film sequences, breaking the clock becomes a powerful symbol of resistance and rebellion. Charlie Chaplin swinging from the minute hand is the carnivalesque version of this, but another scene, from the 1978 version of The Thirty-Nine Steps, brings it to a head. The clock on Big Ben has been set to detonate a bomb at 5:45 p.m., and in order to stop it the hero risks his life to make the clock stop. The crowd on the street watches, both understanding the bomb threat but also seeing a man in danger of losing his life. The culprits inside the clock tower try to kill him but he survives, figuratively stopping time in order to save the day. The heroism of such a scene is offset by the abjection of countless factory scenes, including Chaplin’s, of workers whose bodies become the very fuel of capitalism.

In a clip from a kitschy 1950s movie set in medieval Persia, a group of caliphs gather for the unveiling of the first public timepiece, a water clock commissioned by an ambitious ruler. An older advisor counsels the leader not to let the public have it, because then the people will know what time it is. And, he tells us, “They will ask you what you have been doing with it.”

Literary critic Harold Bloom famously calls poetry “a lie against time,” by which he means that it evokes a kind of presence that belies the relentless passage of life into death and existence into absence.3 Marclay’s The Clock bears testimony to this, as slowly the attention to time seems like a doomed attempt to keep up with it. Eventually each person has to leave the screening, even if they stay to the end of the film. Time is simultaneously a spell and a tyranny. What is remarkable about Marclay’s piece is its use of time-based media to meditate on time. Its simple conceit explodes our ideas of time and space. Both unrelenting and arbitrary, The Clock brings us to see time as something we create, over and over again. But really we don’t create it as much as acknowledge it, and this repetition is both generative and defeating. Time gains its power over us through our endless recognition. It comes to reign over the paradigm of modernity, and its hegemony is revealed in the film’s endless clips of watches, clocks, trains, and airplanes. Through excruciating and sometimes Zen-like repetition, Marclay pays homage to the technological apparatus we call cinema. He compels us to see the edit as the fundamental gesture not just of cinema, but technological modernity itself.

Jumbo or outsize art seems to establish its weight or presence in one of two ways. It either fills us with excess, such as every detail of Hitler’s life, from his film viewing habits to the food he liked to eat, or it narrows its subject down to its essence, like Warhol’s massive skyscraper glowing above the city. The Clock has it both ways. With no beginning and no end, The Clock is both a steady clock tower, and an exhaustive compendium of minute detail. Like many of its antecedents, The Clock’s essential gesture seems unlikely to be repeated again soon, no more than anyone could punch a time clock and call it art for at least a generation after 1980.

Matias Viegener is a member of the collective Fallen Fruit. He teaches in the MFA Writing Program at CalArts.