All together now: art criticism is in crisis. It’s an oft-bellowed complaint these days, and oddly enough art historians are among those fretting the loudest, at least in print. This despite—or because of—the fact that art historians continue to usurp column- space once staked by freelance critics in monthly art magazines. In a further twist, a persistent object of fascination for such historians has been none other than that critic-to-beat-all-critics, Clement Greenberg, a “public intellectual” who famously suspected universities and remained proudly unaligned to academia throughout his lifetime. So what gives? Why haven’t decades of contemporary art’s academicization (not to mention heaping helpings of postmodern critique) succeeded in rendering obsolete this non-tenured journalist-cheerleader of the pre-Microsoft modernist age?

“Postmodernism, in the end, did not finish Greenberg; it rendered him more vital as an object of analysis” (Amelia Jones, p. 3). So declares Caroline Jones, whose new book, Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg’s Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses, admittedly “continues that trajectory.” Boy and how—to the tune of 500 pages of densely-packed, wide-ranging, thoroughly energized and provocative argument. The book’s sheer heft testifies to how extensively the field of contemporary art history organizes itself around Greenberg’s name—a name that can be made to headline not one but both of the basic ways that museums, publishers, art history departments and auction houses administer the artworks of our time, whether the classifying rubric is “postwar” (starting in 1945, in which case there’s Greenberg as cold-warrior of “American-Style Painting,” who famously wrote about “how ‘anti-Stalinism,’ which started out more or less as ‘Trotskyism,’ turned into ‘art for art’s sake,’ and thereby cleared the way, heroically, for what was to come”1) or “contemporary” (starting 15 years later, in which case there’s the more austere Kantian program of “Modernist Painting” and its various critiques from Minimalism to Postmodernism). It’s not nostalgia motivating this preoccupation with Clem, but rather a currently ongoing process, what Jones herself might call “the arc of becoming” of contemporary art history as an institution and profession. Greenberg is pivotal to this process, as origin myth and temporal marker, an initial position around which a field of internally coherent relations can be unfurled, a batch of founding propositions the critical response to which can steer discursive progress, Clem as that in comparison to which we “know better.” Again, everybody: Ich bin ein Greenberger!

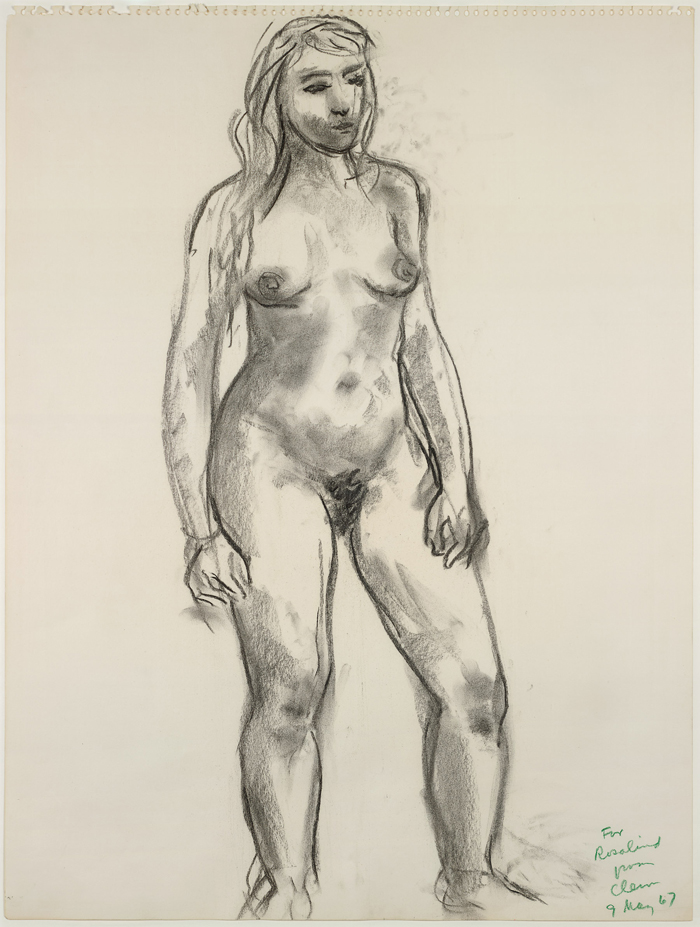

Clement Greenberg, Untitled, 1967. Graphite on paper, 23 3/4 x 18 inches (31 3/4 x 25 1/2 inches framed). Collection of Mike Kelley. The inscription reads: For Rosalind [Krauss] from Clem.

At the obvious risk of abetting its proliferation, Jones sets out to examine this “Greenberg effect” (pp. xix, 4, 317, 343) in order to discover “why we needed” Greenberg (p. xxi)—and how we can do without him.2 She starts by literally cracking the famed critic in two, delving to understand why the character she calls “Clement,” an “obscure adolescent” from turn-of-the-century Brooklyn, sought to construct the subject “Greenberg” as his proper self/name (p. xx). Jones makes extensive use of the recently published letters the 19-year-old English major began writing to his Syracuse classmate Harold Lazarus, in which are recounted debauchery, nightmares, sexual conquests and matricidal fantasies.3 Call this strategic biography: while Jones takes seriously the received idea that Greenberg is nothing less than the personification of Modernism (he is, she writes, an “exemplum” [p. xx], “the modernist subject par excellence” [p. 19]), she does so mostly to distort and displace his use as figurehead. According to Jones, Modernism should be reduced not so much to Greenberg’s writings as to his very body—the spastic, oozy materiality of which she presents as the target of various regimes of regulation and control. A fully cooked, ready-to-serve “Greenberg” ends up contributing to these same regimes by “coloniz[ing]” (p. 65) artworks through his writing, particularly his doctrine of formalist analysis, a “hygienic,” “purify[ing],” “disembodied praxis” and “unifying regime” (pp. 393, 7, 149, 69) that Jones shorthands as “eyesight alone.” In this way Jones aims literally to dismantle Greenberg from his corpuscular inside.

The centerpiece of Jones’s game plan requires that she mimic the critic’s “obsession” with eyesight, but with a difference. For Jones the eye is less a tool refined through the critical judging of artistic form than a “portal” by which the modern world invades the body, rattling its disciplines but also enticing its wayward energies to instrumentalizing ends. Thus Jones dwells on those moments when Greenberg’s shields fail and he’s most vulnerable; i.e., an early incidence of plagiarism, a nervous breakdown while in the army, his misreporting the colors in Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942- 43). Elaborating an analytical approach the roots of which point mostly to Deleuze and Foucault, Jones views the subject as an effect not just of discourse but of visual culture, or what she calls “the modern visibility”—“an extensive, only chaotically coordinated system of illuminations and shadows” that “functions through rules of combination and enunciation (what can be seen and said), and determines available subject positions.”(p. 9) In Jones’s scheme, eyesight doesn’t negotiate between private experience and an outside world but is one of the various mechanisms by which an exterior “folds” (a la Deleuze) to constitute the subject’s sense of “inside.” Somewhat akin to Michael Baxandall’s “period eye,”4 Jones’s “visibility” and the retinal foldings that pock its surfaces are meant to perform that important methodological trick of imbricating text and context, bodies and regimes, art objects and subjects and their larger social, political and economic contexts. (“Explaining ‘the mechanism’ of cultural activity might be the dream of all art histories,” she writes; “certainly it motivates this one.” [p. 9])

The ambitious historical and theoretical claims made in Eyesight Alone are exhilarating, but they also give rise to numerous difficulties. Given Jones’s approach, it matters little whether (and in what sense) it’s true that, as she puts it, “throughout Greenberg’s criticism, the ‘eye’ is a transparent substitute for the ‘I’” (p. 7). If Greenberg didn’t insist on it, Jones certainly would have to. By her Foucauldian lights everything reduces to our various constructions of the “I”—that is, to “subjectivation” as an exercising of power. Greenberg’s private letters are treated like confessions, the self-inscription of one’s body and desire into discourse, while his published criticism is taken as one big instruction manual outlining programs for self-disciplining by his readers. The result is not just that Jones, like so many before her, overestimates Greenberg’s historical role; he’s portrayed as both inflated and deflated at once, snowballing power and influence only as he more effectively channels society’s dominant disciplinary techniques. In this way Jones counters those histories that tend to play up the presence of socialism and Kulturkritik in Greenberg’s position and thus cast him in a more tragic light, as a dissenting voice slowly bled by historical concessions, until he ends up virtually alone and nearly silent yet delusionally triumphant, poaching in his privatizing bath of aesthetic intuition. Jones stages this climax as not extinction but apotheosis of Greenberg’s project; not only does her Greenberg advocate for the bureaucratizing of art and its experience (which places him not just outside but in dramatic opposition to that long tradition—extending from Cooleridge and Arnold to Eliot and Leavis—of which he’s typically assumed to be a part), but his brand of formalism helps make art more compatible with mass spectacle and its emphasis on visuality.5

Paul Sietsema, Clement Greenberg Room, 2002. Scale model for film Empire. Mixed media; 65 x 73 x 103 inches. Installation, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

There are times when Jones’s art historical “dream” does appear within reach, and her descriptions and analysis constellate in expansive and illuminating ways (as in her skillfully layered, chapter-long interpretation of Pollock’s 1943 breakthrough Mural). Yet the core thesis of Eyesight Alone, that Greenberg’s criticism was complicitous with modern systems of domination, is never convincingly established. This is a big problem, since “bureaucratization” is the real subject of Jones’s book, the unmasked culprit behind “the Greenberg effect.” As she states in the opening pages, “regimes of sensory isolation and purification reinforced our appetite for Greenberg’s formalism,” and “these larger structures also governed the regulation of the individual who experienced himself within the author- function Greenberg—from ordering his sight and smell, to realigning his very personality so that it might better occupy a bureaucratic social field” (p. xxvii). Indicative of the book’s overall choppy organization, Jones barely mentions the critical studies of bureaucracy conducted in the 1950s (by C. Wright Mills, David Riesman, William Whyte and others),6 and what she means by “bureaucratization” is only ever glimpsed in one-sentence summaries. We are told, for instance, that “bureaucratization is a large-scale development that we can trace in the modernizing of states and their apparatuses for governing citizens” (p. xix) and that “bureaucratization of the body… [involves] a disaggregation of the senses into compartmentalized units that [can] be administered, commodified, and contained” (p. 11). But the case is never made as to how exactly Greenberg’s aesthetic, no matter how purist, colluded with such bureaucratization. Much is assumed as self-evident, such as the bureaucratic nature of cubism (“linear, gridded, disciplined by repeating brushstrokes, dismembered, crowded and confined within a rectangular field…”) (p. 266). And Jones repeatedly falls back on the clerking job Clem took in 1937 as “crucial” and “consolidating”—“the pivot and the hinge between the unformed and the speaking subject” Greenberg (pp. 32, 209, 22). “It is no small thing,” she insists, “that Greenberg worked as a customs officer; the small-scale bureaucratic habits of civil service resonated with more extensive practices that were being developed to organize consumers, medical patients, art lovers, and scientific subjects in the modern world” (p. xix). Here, as elsewhere in the book, the word “resonated” substitutes for explanation, making the relation between Greenberg and bureaucracy seem at best metaphoric, more a matter of colorful description than a contribution to historical understanding.

The book’s analytical tools are supposedly designed for precisely this task of getting “large-scale developments” to make meaningful contact with the particulars of a “bureaucratized body,” showing how Clem’s veiny eyeballs were but capillaries vibrating in either discord or harmony with power. But it’s the tools themselves that end up serving as Jones’s most relied upon evidence. To focus on something called “the visibility” already compartmentalizes experience, and to say that “the visibility forms the subject Greenberg” (p. xvii) already establishes the critic as conformist (as Mills famously noted about bureaucracies, whether corporate, political or military, they reward people who “fit in”).7 “Subjectivation” is both the chosen lens through which Greenberg is evaluated and the very agenda Greenberg is said to himself choose, that which he’s guilty of imposing on others. Here is yet another instance in which an analytical method creates—in its own likeness—the very “fact” it’s been assigned to analyze, and the scholar’s descriptive powers are paraded unencumbered by any prior and resistant historical reality needing to be described.

Perhaps because Jones’s method privileges such spatializing constructs as “the visibility” and “unifying regimes,” a heavy sense of inevitability and staticness bears down on her book, as quotes pulled from the 1940s get paired immediately alongside ones from the ‘60s (p. 124), and certain events (most noticeably Jasper Johns’s turn to found-object painting and the public debut of his Flag [1954-55]) are simply misdated (pp. 74-75). History is shown to be a series of momentary obstacles to systems that don’t change so much as intensify, and everything, including “agents” like Greenberg, seem to know in advance what they must become. Thus the book, despite its length, can only further flatten and stereotype Greenberg, since granting his criticism any measure of autonomy, or his relation to power any complexity, would betray the argument that he was but a “fold” in, and thus thoroughly co-extensive with, the surrounding bureaucratic technoscape. In no way does it excuse his many failings to credit Greenberg as a dialectical thinker: he saw the avant- garde as both aloof from and dependent on society, optimistic and skeptical in the face of disenchantment and rationalization, and its increasingly concrete paintings he thought vacillated between a successful “unity” (Cezanne, Picasso’s early cubism) and a dreadful “uniformity” (Courbet, Pissaro). Even flatness, considered the very emblem of Greenbergianism, was viewed by the critic as treacherously two-sided, representing both a means to consolidate painting’s separate identity and also a threat to liquidate it into bland wallpaper for bourgeois interiors, a threat epitomized by Mondrian (contrary to Jones’s claim that Greenberg idolized him [pp. 211, 217, 227]). Yet eventually even this threat managed to grow a bright side, as Greenberg decided to join with various museums, galleries and magazines in a widespread crusade to interject a new “period style” into American middle-class culture through the integration of “advanced” art with international architecture and design. Again contra Jones, it was during this period that Greenberg, rather than “exclude any reference” (p. 14) to art’s situatedness in everyday life, made it his top concern.8

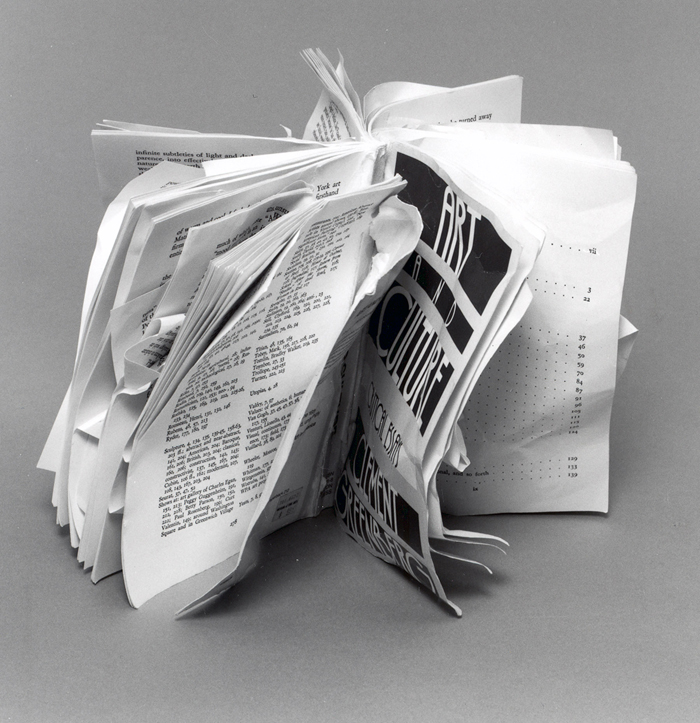

Fred Wilson, Deconstruction of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture, 2001. Courtesy of Georgia O’Keefe Museum and Research Center, Santa Fe, NM. Photo: Herbert Lotz.

Only in the late ‘50s did Greenberg’s criticism really pull back from the world and rigidify. And only then, despite his earlier protests against “surrendering the totality of oneself to a professional role” (by which, “instead of completing yourself by work,” he wrote in 1942, “you mutilate yourself”9), did his criticism feed into the professionalization of art and its criticism. The Abstract Expressionists’ signature style and its painterly language of the self was eclipsed by the modernist series and color-field canvases that spoke a disciplinary, group language—“the language of painting.” Professionalization became a contentious topic. (As Leo Steinberg complained of the color-field enterprise, it was “as though the strength of a particular artist expressed itself only in his choice to conform with a set of existent professional needs… answer[ing] a problem set forth by a governing technocracy.”10) But in a further flattening, Jones treats professionalism as synonymous with bureaucratization, and locates its historical emergence within the field of art criticism at the beginning of Greenberg’s career, not its end. Furthermore, Jones considers Greenberg a bad, or at least underequipped, professional: she scolds him for being a hack philosopher (pp. 63, 105-6, 447 n. 30), for his “stunning ignorance” of art history (pp. 9, 212), for descriptions of artworks in which he “gets it wrong” (p. 219). Greenberg, in other words, lacked training and expertise. Which makes sense, since an institutional base of codified training for critics, one that could erect high educational barriers and weed out the unqualified, didn’t—and still doesn’t—exist. Instead, Greenberg adopted the traditional role of critic-as-amateur, just “one of those critics who educate themselves in public.”11 Eventually he decided he’d had enough and quit regular reviewing, marking perhaps his symbolic “graduation.” (William Rubin would later bestow upon him the title of “dean of postwar American criticism.”12) But the posture Greenberg now assumed was still not really professional, but rather that of a connoisseur. It was only with his willing appropriation by such art historians as Rubin, Michael Fried and others, who harnessed his amateur method to their extensive disciplinary expertise, that Greenberg could be said to make a significant contribution to the instilling of professional standards in the contemporary art world. “The artist as art historian, as scholar of the history of art,” Henry Geldzahler wrote in 1965, “makes the professional art historian his logical audience, and in the past decade it has been in this professional group that much of the early appreciation of new and difficult art has taken place.”13

Why doesn’t Eyesight Alone own up to any of this—namely the crucial role played by the discipline of art history in the very processes the book purports to explain? Jones’s entire project is structured around the absence and unaccountability of her own position as a contemporary art historian. She in fact hides her authority in plain sight, describing her point of view as “liminal” and “aspiring to…neutrality” (p. xxv), thus claiming panoptic powers for her gaze. In an ultimate twist, it is Jones who looms transcendent, disembodied, purified, while Greenberg by comparison appears overly visible, with too much body and no institution or discipline to hide it behind, speaking and acting unendorsed, as if individually, and tainted by material involvements, grubbing around in studios, manipulating reputations and careers, repeatedly watching what are suppose to be his fixed evaluative criteria succumb to the vagaries of time (a fate the historian escapes by mastering time itself as a spatialized construct). Jones can’t even engage with Greenberg’s writing as criticism, since that would admit some common ground between academic expert and pedestrian scribe. While liminality clinches Jones’s critical distance, Greenberg is said to possess “the detachment of a bureaucrat” (p. 5). He is always symptom and specimen under her expert Eye.

But is it possible that this story conceals within itself yet one last twist? Could it be that the “Greenberg Effect” is really a form of fetishism, with the critic at once emptied and overinvested, serving as a projection of, and distraction from, the art historian’s own professionalization? Now there’s a story that should some day be told. How Greenbergianism, which started out more or less as art criticism, was modernized into academic contemporary art history, and thereby cleared the way, heroically, for a credentialed, disciplined criticality without critics.

Lane Relyea is Assistant Professor of Art Theory & Practice at Northwestern University.