After five years of scouting venues, securing funds, and grappling with volatile political instability, including the 2005 assassination of former prime minister Rafiq el Hariri, Israel’s 2006 war on Lebanon, and the 18-month political stalemate that led in May 2008 to the worst flare-up of sectarian violence since the civil war (1975-1990), the Beirut Art Center (BAC) finally opened its doors to the Lebanese public on January 15, 2009. An archetypal white cube gallery housed in an industrial building that sports 1500 square meters of exhibition space, a mediatheque, café, and gift shop, the BAC is anything but typical within the Beiruti artscape. In effect, it is the first non-commercial contemporary art venue in the Lebanese capital. While Beirut boasts one of the most vibrant and versatile contemporary art scenes in the Middle East, it has largely been a festival- and event-based culture. Certainly, the lack of properly functioning state institutions, unresolved sectarian conflict, recurrent confrontations with neighboring Israel, and dependency on foreign funding have made institutional sustainability within the arts difficult. Lebanese artists and curators have become experts in ad hoc-ism, creating alternative organizational and presentational models such as demonstrated by the Home Works Forum, organized by Ashkal Alwan (The Lebanese Association of Plastic Arts) every eighteen months. Two of its editions, October 2003 and November 2005, were each delayed six months due to the outbreak of the Iraq War and the assassination of Hariri. According to its organizers, it is precisely this paradoxical routine that drives them to break and shift relevant questions about dislocation and disruption. Yet, while this might reflect the ingenuity of a particular scene and create possibilities unavailable to overtly institutionalized spaces, it also exacerbates fragmentation in an already fractured city. In addition, though groups of artists collaborate and influence each other, the production of work tends to be monologic in nature, rather than encouraging dialogue with a legacy of practice that is historical as well as conceptual. While of course every work should be judged by its own merit, giving contemporary art in Lebanon a physical home roots it and places themes and ideas in a larger context.

A thread running through the works of many Lebanese artists within the country and its diaspora is an examination of the ghosts of the civil war and the nation’s ensuing amnesia. Featured prominently in the work of artists who are well-known within the international establishment (such as Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Lamia Joreige, Rabih Mroué, Walid Raad, Lina Saneh, and Akram Zaatari) are themes having to do with the excavation of personal and collective narratives, the thin line between the mediation of historical truth and the instrumentalization of truth fabrication, the impossibility of representation after disaster, and the role of the archive. An emerging generation of artists such as Ziad Antar, Mounira Al Solh, and Raed Yassin incorporates these topics, yet does not shy away from using humor, reflecting upon their own complex positions as artists, and celebrating pop culture and the mundane. It is no surprise then that the first three exhibitions conceived by the BAC—Closer, and the concurrent exhibitions Exposure 2009 and 4—would be heavy on personal narrative and history.

Closer set out to show work “drawn from personal and intimate stories, which create a space to reflect on experiences both common and unique, familiar and without precedent, public and intensely private.”1 Typically, exhibitions in Beirut tend to present regional artists and international artists separately. Closer offered an unusual encounter between the two groups. The highly politicized and documentarist works of Akram Zaatari and Palestinian-American artist Emily Jacir were juxtaposed with early work by Albanian Anri Sala. The poetic personal histories of Lebanese pianist and composer Cynthia Zaven were contrasted with American-born Canadian Lisa Steele’s classic video Birthday Suit—with scars and defects (1974). Many works shown in Closer are markedly older and they reference vested interests in the body as a physical site of memory and of the imaginary. They also propose the body as a locus that can come apart and can suffer violence, especially within a political and feminist context.

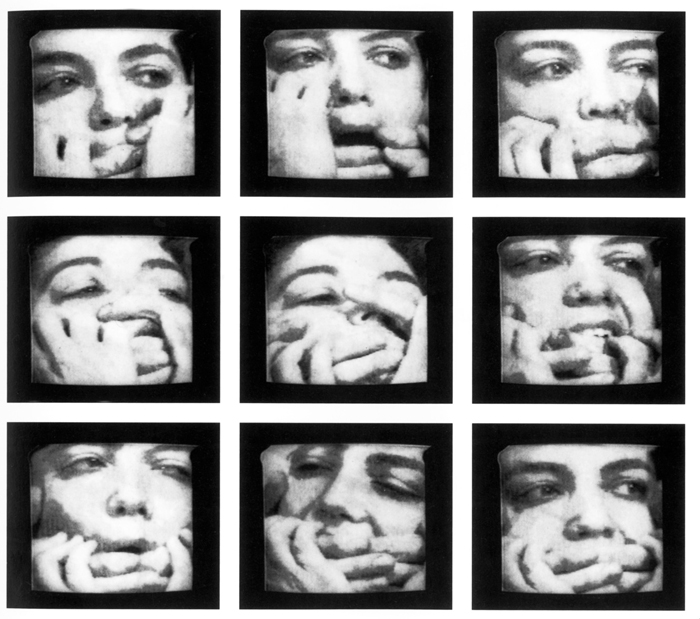

Mona Hatoum, So Much I Want to Say, 1983. Black and white video, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

This vulnerability is best exemplified in the Lebanese-born Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum’s influential piece So Much I Want to Say (1983). A short, repeating sequence of grainy, still images of a woman’s face, which is gagged by a male hand, is accompanied by the words “so much I want to say,” repeated over and over again by a female voiceover. This work, first shown in a slow-scan satellite transmission between galleries in Vancouver and Vienna, is a de facto registration of a performance. An obvious disconnect is revealed between the (im)possibility of technology to convey a certain message and the desire of the speaker who finds herself stifled and reduced to uttering her wish ad infinitum. Hatoum’s work draws on the difficulties of communication and censorship against the backdrop of gender relationships and other political power structures. So Much I Want to Say was made shortly after the 1982 massacres of Palestinian refugees in the Beirut camps of Sabra and Shatila, which led to major international outcry but did not improve the conditions of Palestinians in Lebanon, or elsewhere.2

Playwright and performance artist Lina Saneh’s Body pArts (2007-2008) attempts to circumvent Lebanon’s religious law that forbids cremation. Saneh envisions this project as a means to resist a “conservative religious social mentality” at play in Lebanon by attempting to conquer as much of the terrain of her body as she can. On the project’s Web site, she invites artists to add their signatures to pieces of her body, thereby transforming it into “a collection of art pieces duly signed by different artists around the world.”3 After her death, Saneh desires that her body be cut up and each piece sent to its new owner. Those who sign are contractually bound not to alter the body part, to preserve it from deterioration, or otherwise to burn it. However, the other artists have no remunerative rights over Saneh’s body parts and consequently cannot make a profit from them unless Saneh decides to sell the piece. Nevertheless, after her death artists are free to exhibit their parts—or the burnt ashes—at will. Saneh calls into question artistic authorship, copyright laws, and the readymade, interlinking these debates with the artist’s body, which literally becomes a corpus of work. Unfortunately, the piece was unengagingly represented at the BAC by a computer terminal and a life-size cutout of Saneh in which her features were blackened (incinerated or disembodied), except for her trademark red hair. Once placed in a white cube, the participatory nature of this performative and collaborative work was lost.

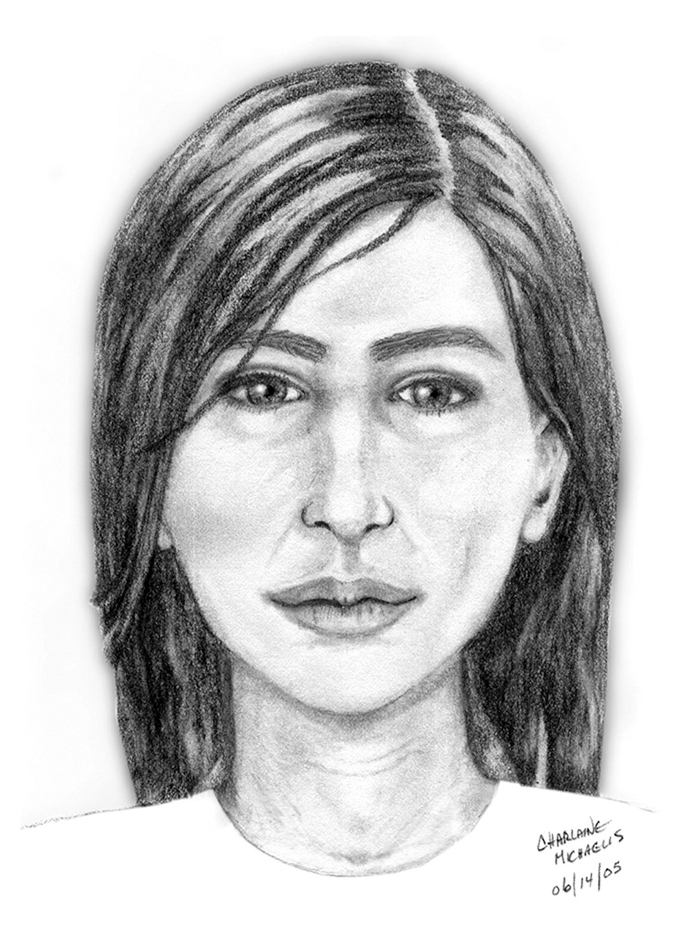

Jill Magid, Composite (detail), 2005. Composite drawings, letters, soundtrack. Courtesy of Yvon Lambert Gallery.

Jill Magid’s installation in Closer, Composite (2005), explores the re-mediation of intimate memories and their visualization. Magid began by writing letters to former lovers in which she asked them to describe her face in detail. She gave the resulting descriptions to forensic artists, who then created composite images of her face. The resulting drawings, projected from slides onto the gallery wall at roughly life size, show the various “reconstructions” of Magid. The installation includes the original letter the artist wrote to her lovers, as well as a voice recording of a former boyfriend “remembering” the features of her face. All these components make up the process of materialization, from the initial request to the end product. Funnily enough, they “reproduce” the artist in a serial way wherein none of the reproductions really resembles the original. Descriptions and interpretations are in that sense always approximations of the real, but can never constitute it. The artist’s choice to project reproductions of the drawings, rather than show the actual documents, by corollary repeats this process of mediation.

The intricate dynamics of the historical real, its materialization, and modes of display are also present in Cynthia Zaven’s contribution to Closer, titled Missing Links (2007), which consists of a large black box fitted with interior speakers. Arranged on top of the box is a series photocopies of personal documents accompanied by commentary. Created during her artist’s residency in Istanbul in 2007, this is a highly personal project for Zaven, who is of Lebanese-Armenian descent. With Missing Links, she attempts to reconstruct the life of the grandfather she never knew, mixing such details as his birth date in Constantinople in 1893, his occupation as a painter in Beirut, and his death in Beirut in 1957, with family documents including his passport, a few photographs, and postcards. Zaven mainly assembled this work from childhood stories told to her by her mother and other family members. Her attempt to retrieve his traces in Istanbul was met with great difficulty, as the small remaining Armenian community in Istanbul lives in seclusion, almost in secrecy.4 Their tragic history and hidden lives are reflected in the soundscape of the installation, which consists of murmurs and whispers in Armenian alternated by piano key strokes and the crackle of turntables, which provide a sense of time past. One has to strain at times to hear the whispers emanating from the black box of literally concealed information. The fact that the facsimiles of the documents do not to appear authentic and are loosely placed on top of the box, rather than encased in a vitrine and thereby monumentalized, echoes an imagining of a historical narrative where the artist’s speculation links the factual dots.

Zaven was also featured in the BAC exhibition 4. In her 26-minute, 8-channel installation Octophonic Diary (2007-2008), the audience can listen in a shelter-like space to a soundscape composed from the artist’s own archive. Here Zaven combines personal recordings of sounds extracted from home videos of the 1970s and 1980s with text excerpts by Pierre Schaefer, songs by Joy Division, and her own earlier musical compositions. As in Missing Links, the piece sounds eery and melancholic; the personal is ultimately transcended and morphs into an experience detached from the artist’s private concerns. It is a pity in this respect that the placement and presentation of both Missing Links and Octophonic Diary were inadequate. Both require concentration and intimacy. By placing the Missing Links’s box too close to the staircase and the venue’s book shop, these necessary conditions were unmet. Moreover, the robustness of the black box and the disposable quality of the copied documents did not do justice to the subtlety of the ideas presented. For Octophonic Diary, the experience would have been far more intense and affecting had the artist dispensed headphones rather than using a distributed speaker system.

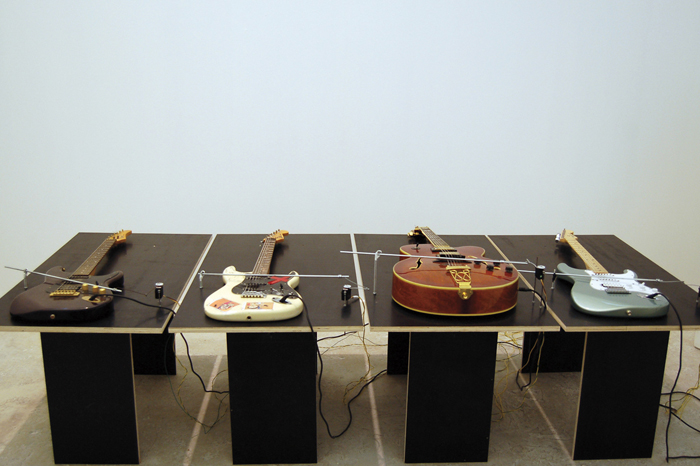

Charbel Haber, When No Body’s Around (The Cables between Us), 2007-2008. A sound installation and musical piece for 8 electric guitars with no performers. Courtesy of the artist.

In these examples and others, it seems that the BAC is still coming to grips with its spatial configuration and the technical challenges of three-month exhibition cycles. During the exhibition 4, which showcased the results from a technology and art workshop by four Lebanese artists (Charbel Haber, Kinda Hassan, Mounira Al Solh, and Zaven), this became particularly evident. When I visited the show, Haber’s sound installation When No Body’s Around (The Cables between Us) (2007-2008) simply was not functioning. on display were eight electric guitars that by means of a mechanical device were supposed to play by themselves. The piece was quite reminiscent of Saâdane Afif’s multimedia installation Black Chords Plays Lyrics (2004- 2007), in which 13 computer-controlled guitars distributed over a space produce chords from morning until evening. The whole point of Haber’s piece is the auto-generative capacity of technology. Without intervention by a human artist—in this case a musician—creation is still possible. By allowing dead technology and muted instruments to remain on display, Haber’s exercise loses its raison d’être. Hassan’s three-channel video installation Ashoura—Untitled (2007-2008) also disappointed in presentation, but even more so in content.5 The day of Ashoura is quite a spectacle in Nabatiyeh (South Lebanon), with throngs of men beating their chests and slashing their foreheads with blades to ritually commemorate the killing of the religious martyr Imam Husayn Ibn Ali. This video bears resemblance to Lebanese artist Jalal Toufic’s well-known video Ashura: This Blood Spilled in My Veins (2002). While it is conceivable that Haber might have not been familiar with the work of Afif, it is unlikely that Hassan would be unfamiliar with Toufic’s work. In addition, Toufic’s iteration manages to achieve a visual and intellectual poetics, while Hassan’s video does not go beyond mere registration and exoticization.

4 was held in tandem with the exhibition Exposure 2009, a platform to support emerging Lebanese artists who proposed new works or pieces that had not before been shown in Lebanon. While in Closer the body—or its absence—functions as a vehicle for narrating personal histories, Exposure is marked by an almost methodical distancing on part of the young artists. The most tried and tired example of documentarism can be found in Sirine Fattouh’s Lost and Won (2008), a video and photography project in which she asked women all around Lebanon what they had lost and what they had won. Snapshots of the interviewed women are “artfully” arranged on a gallery wall, flanked by two video monitors, where the respective interviews can be viewed. It has all the right ingredients in an era of “engaged art”: women (veiled and not) and tales of love, war, and loss. Perhaps it is the performance of an expected and well-rehearsed formula that makes it so unchallenging.

Karine Wehbe, Tabarja Beach 1, 2008-2009. Color photograph, 110 x 90 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

The most inspiring works of the Exposure exhibition were those where the artists made manifest their proximity to the subject matter, either in an uncanny or humorous way, allowing art to do what art does best—to operate on multiple levels. Karin Wehbe’s striking photographs Tabarja Beach 1 (2008-09) disclose images of dilapidated Lebanese beach resorts dating from the late ‘60s that during the civil war became getaways from the horrors of war. Now empty and fading, the promise of utopia these sites encapsulated has faded as well. Wehbe photographs herself in these settings, as if living out her memory again. one photo shows her with a friend reclining elegantly along the edge of an empty pool. The scene is deserted, the parasols skeletal, and the dramatic background of the Lebanese coastline appears menacing: a concrete wasteland of dreams. These images evoke staged holiday snapshots that strangely find themselves out of time and out of place.

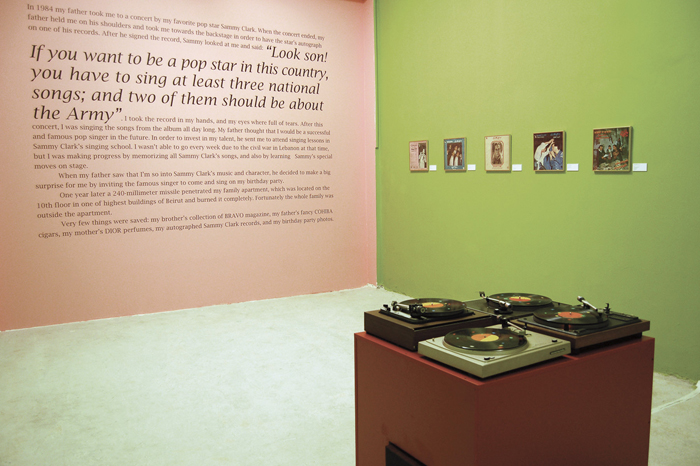

Raed Yassin also places himself (or rather his childhood persona) in the midst of his installation The Best of Sammy Clark (2009). Partly homage to Sammy Clark, the singer whom Yassin describes as “the most powerful voice during the civil war” and partly fictional narrative, Yassin’s recent project deconstructs nationalism and the history of Lebanon’s civil war through the vehicle of pop culture.6 A highly directive text panel mounted on the front wall recounts how, as a child in 1984, Yassin was taken backstage after a Sammy Clark concert and thereafter became the singer’s protégé. In the same year, after a missile of the warring militias hit the family’s apartment, few things but Sammy’s records were salvaged from the wreckage. Four turntables fitted with Sammy Clark LPs play two nationalist songs and two love songs, respectively. Stickers plastered across the surface of the records result in a looped soundscape; as the exhibition continues, the wear and tear on the vinyl increasingly distorts the sound. On the left wall of the installation are childhood images of Yassin with Sammy Clark at family parties. The photographs play simultaneously on the dynamics of intimacy and voyeurism. Here, one also wonders at the authenticity of what is presented. Are these images manipulated in Photoshop or is our perception just off kilter? on the opposite wall are record sleeves autographed by Clark. All are dedicated to the artist, “the miracle child,” and they encourage Yassin to sing for Lebanon and peace. Capitalizing on sentiment and nationalism, the sequence of LP sleeves on the wall lays out a history of Lebanon through the years of war.

Raed Yassin, The Best of Sammy Clark, 2008. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

In effect, Yassin’s installation The Best of Sammy Clark functions as a primer on how to become a successful singer (artist) during times of conflict. At the same time, it operates as an ironic reference to the expectations heaped upon Lebanese artists, especially within the context of a show of emerging artists such as Exposure. In the past five years, the Middle East has become the new hotspot for contemporary art, playing host to a flurry of international curators parachuting in and out of the region in search of the next hottest thing. Artists, both established and emerging, often find themselves negotiating the complexities of the pressures of the international art world (and the limitations of geographical representation), as well as local demands. In the case of the shows at the BAC these issues have not been ignored. Rather they stand at the heart of how the BAC positions itself as a local, yet internationally engaged, institute. Closer, Exposure 2009, and 4 all offer testimony that these debates are still ongoing and unresolved.

Nat Muller is an independent curator and critic based between Rotterdam and the Middle East. She has taught at the Willem de Kooning Academy (NL), ALBA (Beirut), the Lebanese American University (Beirut), and AUD in Dubai (UAE).