Connie Samaras, Dome and Tunnels, South Pole, 2005. Chromogenic light jet print; 48.5 x 62 inches. Courtesy of the artist and de Soto Gallery.

In 2004, Connie Samaras traveled to Antarctica under the auspices of the Office of Polar Programs (a division of the National Science Foundation). She was invited through the Antarctic Artists and Writers Program (AAWP) to document the “liminal spaces between life support architecture and extreme environment.” Since 1992 the OPP has enticed artists and writers to the Pole to increase public understanding of the region as well as promote awareness of the agency’s endeavors. During the Clinton administration, the OPP struggled to remain relevant and even to survive. It was threatened with severe cutbacks that would have rendered impossible the 1994 South Pole Station Modernization (SPSM) project, a $153 million upgrade to the dilapidated Amundsen-Scott Station. In the end, the SPSM was pulled back from the brink financially. In 2000, Raytheon Polar Services Company was chosen by the NSF to be the “primary support contractor” for all US research efforts at the South Pole, including construction of the new station.

Samaras arrived in Antarctica at the midpoint of the SPSM. Her photographic proposal must have been perceived by the OPP as quite timely, as it perhaps would showcase the first phase of the new modular Amundsen-Scott Station, completed during the preceding austral summer. Samaras called her project V.A.L.I.S. (vast active living intelligence system), borrowing the title from a Philip K. Dick novel about transcendence and technology.

As awed as she was by her environs, Samaras remained mindful of her mission to record the relationship between architecture and icescape. In a journal entry written during her six-week stay she seems determined to quash the impulse to capture the “wholeness” of the region on film–a goal she felt was ultimately as unachievable as it was hackneyed. She likened such efforts by others photographers there to “ants trying to drag a planet back to their nest.” Exerting considerable restraint, she turned her back to the Antarctic’s sublime eminence, focusing her medium- and large-format cameras instead on the comparatively mundane edifices of the research station.

Connie Samaras, Buried 1950’s Station, South Pole, 2005. Chromogenic light jet print; 38 x 48.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and De Soto Gallery.

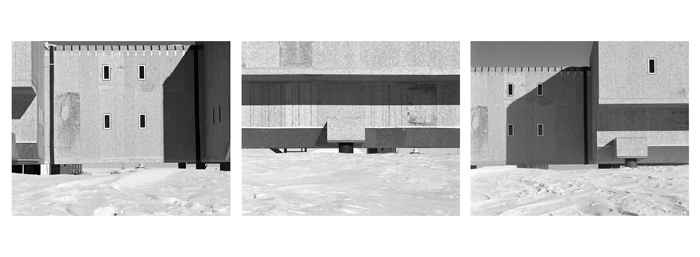

In many photos, Samaras documented the process of inevitable interment as harsh, driving winds push drifts of ice and snow across the frozen polar landscape and eventually engulf anything in their path. In Buried 1950s Station (2005) only tiny nubbins of torqued wooden buildings protrude from twinkling rivulets of ice–traces of the past that quite soon will disappear completely (or by this reading may already have). Even the new, not yet completed research station looks as if its architects have anticipated its eventual sacrifice to the elements. Noticeably, valuable funds have not been wasted dolling it up. In images such as Amundsen Scott Phase III Triptych (2005) the modular structure is plain–a dowdy chain of plywood quads–in comparison to the futuristic Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome built there in the 1970s.

Connie Samaras, Triptych, Amundsen-Scott Station, Phase III, 2005. Chromogenic light jet print; (3) 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and De Soto Gallery.

Although Samaras deployed framing strategies to foster a sense of what she calls “speculative landscape,” she shot the V.A.L.I.S. series, in her own words, “straight.” In this regard, her relationship to the architectural object seems almost clinically neutral. Her photos participate in a prevailing photographic trend toward imagery that appears completely objective in register. The mainspring of this aesthetic style is said to be the large-format “record-pictures” of obsolete industrial architecture taken 40 years ago by German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher. The Bechers’ approach has been highly influential, inspiring Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Axel Huette, and Candida Hoefer, as well as many other photographers of urban landscape and architecture.

As the style has become popular, the somewhat pejorative-sounding term “deadpan” has stuck (possibly alluding to the blank expressions of portrait subjects such as those documented by Ruff). A reluctance to impose a conditional reading of the image upon the viewer is a hallmark of the deadpan approach.1 Further, the conventional mandate of documentary photography to capture the “decisive moment” is vastly diminished. (In effect it becomes an impossibility given the unwieldy, large-format cameras favored by its practitioners.) By “removing any hint of rhetoric or persuasion,” this emotionally flattened imagery is thought to eschew photography’s customary claims to truth telling.2

In the Bechers’ photographs, this last dimension of deadpan has been troubling to some. For within the process of aestheticizing the architectural object, a subtle proclivity to bypass its historical context emerges. A few art historians have felt that in order for the Bechers to create effective conditions for an “undisturbed contemplation” of the architectural object, all sociological and historical references to postwar Germany had to be “excised” from the imagery.3 For this reason they have criticized the Bechers’ work as displaying symptoms of a “repressive apparatus.”4

The significance of deadpan photography has grown over time. Photography curator Charlotte Cotton asserts that through its emphasis on emotional detachment, monumental scale, and “breathtaking visual clarity,” deadpan moves the medium outside the “hyperbolic, sentimental and subjective” and propels it to a more central position in contemporary art.5 From an aesthetic perspective, deadpan photographs can be very enticing to the eye. However, they can also appear formulaic and consequently much more about style than substance. So very obdurate are some deadpan images of landscape and architecture that our gaze practically bounces off the surface, unable to gain any entry to their raison d’etre. Such photographs function at the level of what Roland Barthes would call “unary” imagery:

The Photograph is unary when it emphatically transforms “reality” without doubling it, without making it vacillate (emphasis is a power of cohesion): no duality, no indirection, no disturbance.6In Camera Lucida, Barthes expressed

concern that by sublimating it into an art form, photography’s underlying “madness” (the thing that “keeps threatening to explode in the face of whoever looks at it”) would be tempered, even domesticated.7 He was equally disturbed by the proliferation of unary and banal photography, which he felt contributed to an overall societal “reversal” in which people now live according to a “generalized image-repertoire.”8 For Barthes, the generalized photographic image is problematic because it “…completely de-realizes the human world of conflicts and desires, under the cover of illustrating it.”9

In its most banal and ahistorical manifestation, the deadpan photograph preemptively confounds any prospect for sympathy on the part of the viewer. It possesses capacity neither to attract nor repel beyond general curiosity, nor to trigger emotions such as pity, horror, or melancholia–those elements of unexpected trauma unleashed by photography that Barthes has termed its “punctum.”

It is understandable why Samaras might be inclined to take a deadpan approach. Doing so would distance her images from the lengthy history of picture taking in Antarctica. The burden put on the medium during the many years of polar exploration has been heavy. Because expedition funding was often tied to tangible proof of accomplishments in the earliest days, photographers such as Hubert Ponting were hired to procure the “money shots.”10 So important was this documentation that cumbersome photographic plates commonly took priority over food and other essentials.11

Samaras is quite accomplished at evading this aspect of the past. Her success is especially curious given that her subject matter for the series is fully and partially buried buildings. It has long been noted how built forms “stand in” for the human form.12 On some level, one would think steadfast Antarctic themes of endurance and perseverance, as well as terror, capitulation, and obliteration, would creep into the photos somehow. Pictures from the brutal “heroic phase” of South Pole discovery (1890-1910) are tragically compelling. They capture the dazed expressions of prematurely aged men, their visages scorched black with frostbite. Horrifically gruesome tales of icy self-immolation written by explorers whose journals were retrieved from their frozen corpses often supplemented the images. But the stylish V.A.L.I.S. photos do not go there at all. Instead, they are presented almost as if their referents never had a place in the living world and as such could not be marred by the prospect of impending loss.

By 2005, it was common knowledgeamongst workers at the station that the decrepit Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome was on its way out. For more than 30 years, this sheltering structure was the single most identifiable feature of the South Pole. As vulnerable to the crushing weight of wind-driven snow as its architectural predecessors, the worn out dome had begun to collapse. When the NFS first announced it would be dismantled, a collective cry of “Save the Dome!” was heard from nostalgic Antarctica junkies, scientists who had been posted there, and even the US Navy Seabees who built it. (A lost cause, the outcry has since dwindled to near silence. ) In 2006, contractors began the arduous process of hauling out components of the dome to the coastal McMurdo Station, where it will be transported back to the United States for disposal.

Given the stake Buckminster Fuller placed in the future, one would expect the irony of this immanent erasure to be palpable in the photos shot by Samaras during this period. Oddly, it is not. InDome and Tunnels (2005), for example, the structure gleams prettily against a backdrop of vivid blue sky. Though plainly mired in deep snow that has contributed to its ruination, there is no sense of despair attached to it. Could it be that we are so culturally programmed that we can only read this image as an icon signifying a utopian future?

Connie Samaras, Day/Night Divide, Polar Plateau, 2005. Chromogenic light jet print; 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and De Soto Gallery.

In the afterglow of her Antarcticadventure, Samaras and others who would speak of her project have been tempted to linger upon sensational aspects of her own narrative (such piercing details as her nightly ritual of applying superglue to the tips of fingers split open by the intense cold). The impulse to append her radiant yet detached C-prints with personal stories suggests that while the imagery is indeed formally powerful, some expectations of it hover unmet. We find ourselves scanning the unremarkable features of the new South Pole Station’s structures and the gaping unpeopled emptiness of the surrounding landscape for something that patently is not there. Like travelers to a distant and exotic place, we as viewers look for something we feel we may have lost in ourselves. What we seek is authenticity.

In his work on the underpinnings of contemporary nostalgia, cultural scholar Andreas Huyssen has commented upon the resiliency of the ideology of authenticity, despite generations of modern and postmodern dismissal:

The desire for the auratic and authentic has always reflected the fear of inauthenticity, the lack of existential meaning, and the absence of individual originality. The more we learn to understand all images, words, and sounds as always already mediated, the more, its seems, we desire the authentic and the immediate.13

Elsewhere, Huyssen has said of authenticity that it “always comes after” (his italics) and is experienced “largely as memory and primarily as loss.”14 He links the notion of authenticity to our contemporary obsession with the ruins of modernity and our desire to preserve them, impulses he feels hide”…a nostalgia for an earlier age that had not yet lost its power to imagine other futures.”15 In the contemporary moment, our compulsion to preserve has become nearly catastrophic, given the gargantuan amount of intellectual and material stuff we are able to store and retrieve. So much has this become the case that selective “forgetting” is an absolute necessity. But decisions about what we keep and what we let go of are naturally fraught with tension. This becomes even more problematic when it comes to aspirations that have moved from the category of “future” to “past,” from “maybe” to “might have been.” Whom do we trust to make these choices? As cultural historian Harald Weinrich has quipped:

…Is there really an art that allows us to determine today what can be forgotten in the future? And where is this art taught, since all the futurologists have long since retired?16

Our anxiety about the future redoubles the yearning for authenticity. With reluctance, we must now accept the phenomenon of global warming as fact, after nearly ten years of self-delusion and prevarication. This great unknown sobers us. The philosophical relativism that has been in vogue during our time provides precious little comfort. It is increasingly difficult to imagine any future with any degree of confidence.

After decades of indifference, our thoughts have turned again to the Polar Regions. These endangered ecological zones figure prominently in discussions about the future, both as harbingers of change and as potential treasure troves of exploitable resources. With regard to this second aspect, we realize Fuller was in a sense correct: the future is modular. As embodied in the new Amundsen-Scott Station, however, the future is as bleak and generic as an industrial park complex. Moreover, our government has entrusted the care of this future to Raytheon, giving substance to the anxieties of visionaries like Fuller as well as paranoiacs like P.K. Dick about the insidious power of military-industrial conglomerates.

We want to be moved by Connie Samaras’ Antarctic photographs, as we crave to find in them a modicum of the authentic (and by extension, some semblance of unsullied hope). Samaras seemed to intuit this as well. She hedged her lovely deadpan photographs by presenting them in juxtaposition with two digital videos: Cargo Plane Returning from McMurdo Station to Christchurch, New Zealand and Untitled, Ross Ice Shelf (both 2005). In the first, a chilled looking fellow awakens from an uncomfortable slumber briefly to glare with annoyance at an invasive camera. In the second, a Weddell seal catching its breath stares up trustingly at the photographer from a hole in the ice.

It was the close interaction with the animal, not the human, which offered up a prospective encounter with the authentic. Even though it employs the same visual strategies of straight documentary, the extended medium close-up shot is transformed beyond some mere “Animal Planet” moment. More than anything, the video was a kind of poltergeist set loose in the gallery. The seal’s deep respirations emanated subtly from the lower level, disturbing the quietthroughout like the insistent mechanical functions of an old-fashioned iron lung. Here was the untidy rupture, an aural manifestation of the Barthean punctum that wrested attention from the transfixingly deterministic needs of the present. In the resounding plaint by this specter, the noise of hope could be heard, as well as admonitions about the consequences of forgetting the future.

Kristina Newhouse is a curator who lives in San Pedro.