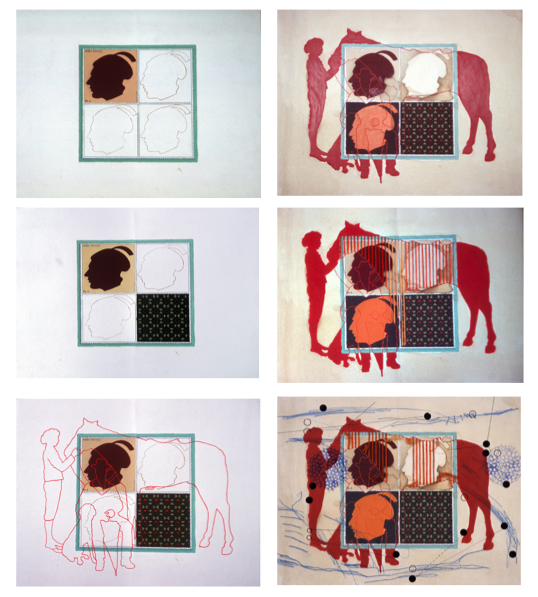

Hasnat Mehmood, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Saira Wasim, Talha Rathore, and Muhammad Imran Qureshi, Karkhana #3 (photographic documentation of the interventions by each artist), 2003. Courtesy of the artists and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

A revival—say, of Mughal miniatures or Chinese brush painting—is like a partial recollection. The most interesting parts may be unremembered, and may need to be creatively reconstructed. The Karkhana collaboration, which helped breathe new life into Mughal miniature painting after a sleep of over a hundred years, and which I saw recently at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, brought to mind a show two years earlier of collaborations around an old Chinese landscape. Both projects, with their reassertion of the mastery of traditional culture over its colonial aftermath, represent successful attempts to invent a non-Western contemporary art.

The six artists who came together in the Karkhana project are graduates of the miniature painting program at the National College of Art in Lahore, Pakistan. Shahzia Sikander (who was not in this show) earlier graduated from the same program, and showed how miniature painting could be purveyed into an illustrious career in the West. Some of the six are now teaching in the program; others are living in New York, Chicago, and Melbourne. For the Karkhana project, each of the participating artists took two small sheets of wasli paper and began to paint on it, using miniaturist techniques. The pages were then circulated round robin by courier until each artist had painted on every page. The twelve sheets were exhibited together with five or six works done by each artist individually, which allowed one to detect their trademark styles and imagery within the collaborative paintings. Some of the historical miniature workshops (karkhana means “workshop” in Urdu) also worked collaboratively, passing their work between specialists in drawing figures, animals, gardens or architecture. So what has been revived here is a mode of group production as well as a form and a technique.

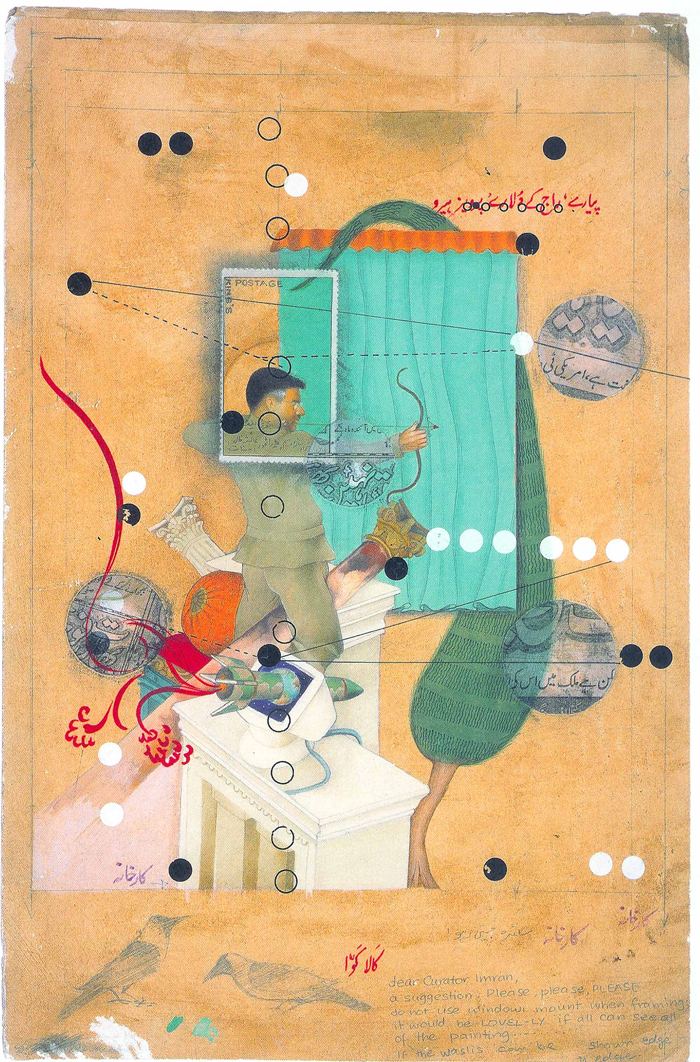

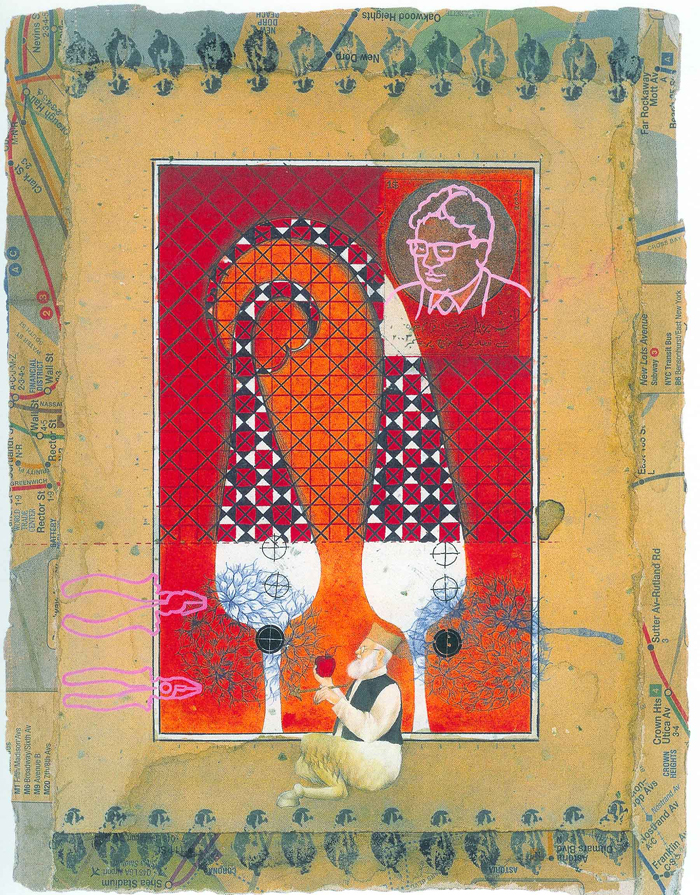

The Karkhana paintings are typically busy, with a very wide range of compositional and color schemes. The imagery includes British colonial postage stamps, a tiger, Islamic marquetry cypress trees, a dagger, three polo players, George W. Bush shooting a bow and arrow, Pervez Musharraf shooting a bow and arrow, several missiles, several courting couples, a pair of scissors, a tulip, a mullah with the legs of a goat, and strips of a New York City subway map. The artists have explained that much of this imagery has a political resonance, some referring to British colonial rule. The outline of two figures traced from an old photograph is said to show King George V after a successful tiger hunt; the tiger represents India. Such references appear to complement or parody each other within the paintings. To non-Pakistani viewers they may not be fully accessible without explanation and in some cases decorative elements may blur or even cancel out political ones.

By the mid-nineteenth century, loss of Mughal patronage, imperialist disparagement of indigenous art, and the advent of photography had put the older miniaturists out of business. When the NCA in Lahore first tried to revive this style in the 1980s, many miniature albums had been dispersed or sold abroad; students copied Mughal, Persian and Rajasthani miniatures from black-and-white photographs and art history books. They learned how to glue together the layers of wasli paper and to burnish it; how to grind their own pigments from semi-precious stones and bind them with gum Arabic; how to make squirrel-hair brushes, including those with a single hair. The mainstream Pakistani art world snubbed these “craft” practitioners, while their conservative teachers raised eyebrows when they left off copying and began to play with contemporary imagery. Eventually they mastered what turned out to be for them a new visual language, superseding Western ones that they felt had become saturated and unable to say anything new. Women have been prominent in achieving this mastery; four of the six Karkhana artists are women.

It was apt that a painting genre intended to be bound into books and enjoyed through intimate contact should be accompanied in this show by a sumptuous book reproducing every stage of each Karkhana painting and including essays on the history of Mughal miniatures, the NCA program, and artistic collaboration generally; and on the paintings’ politically subversive aspects, the steps by which each was made, and the materials and techniques used. Apt too that this book, which serves as exhibition catalogue, should be the fruit of a collaboration between the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, CT, which organized the show, and Green Cardamom in London, which promotes the work of South Asian Muslim artists.1

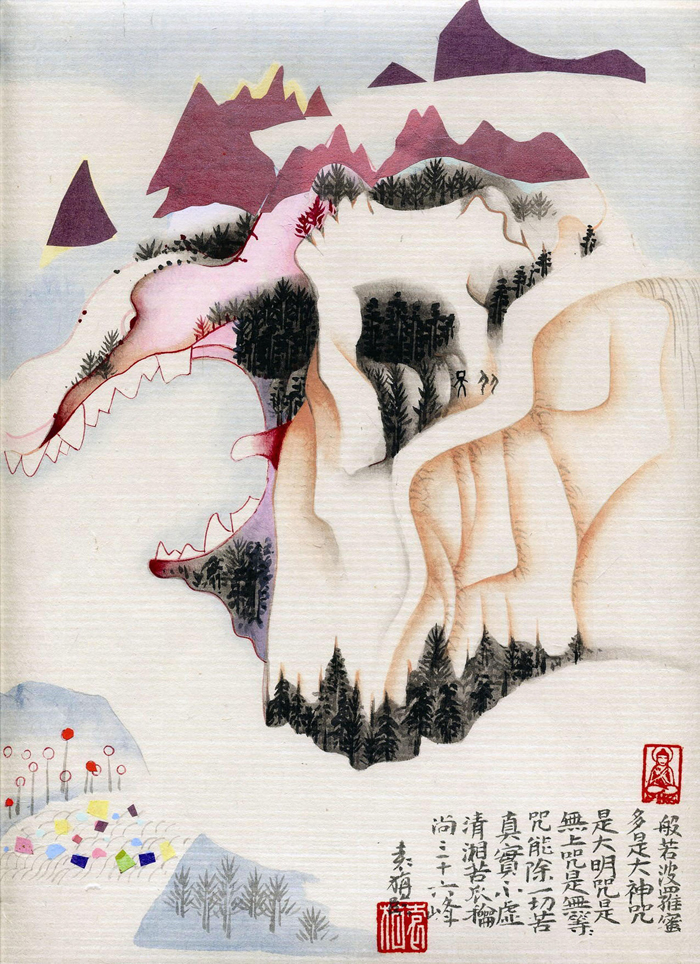

Bringing in the story of the Chinese landscape mentioned earlier will sharpen our focus on the Karkhana project and its Pakistani artists, since the similarities appear to be systemic and not incidental. In the case of the Chinese landscape exhibition, Through Masters’ Eyes, two departments at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—Asian Art and Modern and Contemporary Art—decided to mount a collaborative exhibition and invited the Taiwanese artist Lee Mingwei to do a project centered around a work in the Museum’s collection. Lee, who had lived in Chan Buddhist and Benedictine monasteries, chose a 1694 brush painting of Mount Huang in Anhui Province by Shitao, a monk who, like Lee, had been separated from his home.

Lee organized a collaboration made up of two chains of artist-copiers—five in Taiwan and six in the West (mostly New York) and sent good photocopies of the Shitao ink painting to the lead artist in each chain, who copied it by hand and sent the copy to the next artist, who sent his or her copy of the copy still further down the chain.2 Thus the grand Chinese tradition of copying masterpieces was continued with a postmodern resonance through appropriation. Eventually all eleven copies (interpretations, really) were exhibited in the Museum alongside the original. A Chinese accordion-fold album containing facsimiles of the original and the eleven interpretive copies was made available, allowing viewers intimate contact in the turning of the pages. What was revived here was not only a genre and a fashion of producing works in series but a mode of audience reception.

Shitao (China, 1642-1707), Landscapes, dated 1694. Part of eight-leaf album, ink on paper and ink and color on paper; 27.94 x 22.22 cm. Los Angeles County Fund. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo (c) 2004 Museum Associates/LACMA.

Yuan Jai (Taiwan), Untitled (after Shitao), 2004. Ink and color on paper, collage; 13 3/8 x 10 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and the National Museum of Taiwan.

Several parallels between Lee’s project and the Karkhana one suggest themselves. For one, both exhibitions hinge on their processes of collaboration. Lee is known as a conceptual artist who explores situations of mutual trust and vulnerability with audience members. In this project, the museum entrusted Lee with choosing the other artists. Lee in turn achieved a relationship of trust with the artists, whom he visited personally to deliver and pick up their work. In a similar way, trust formed between the Karkhana artists, who came to know each other well. It allowed Nusra Latif Qureshi to remove part of a collage added by Hasnat Mehmood, and M. Imran Qureshi to cut some red threads sewn through the wasli by Talha Rathore. It happened that all of Lee’s artists found an image of the Shitao painting on the website of LACMA’s permanent collection and asked if they could use it. Lee, who is fascinated both by serendipity and by the way complex situations proliferate, agreed, since allowing the artists alternate models complicated the range of their artistic choices. In much the same way, when a postman folded Karkhana #4 to squeeze it into a mailbox, Aisha Khalid accepted the serendipitous fold by drawing a dotted line over it. Saira Wasim allowed parts of her underdrawing to show through to signal acceptance of the vagaries of her own process.

Cristian Alexa (Romania, active United States), Untitled (after Shitao), 2004. Collage on paper; 13 3/8 x 10 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and the National Museum of Taiwan.

Chinese horizontal scrolls, which are unrolled and viewed section by section, and albums, with their accordion folds, do not expose themselves all at once like Western paintings. Instead, they present sequential experiences. Lee’s accordion-fold facsimile book at LACMA did this; so too did photographs of the six stages of each Karkhana painting presented in the exhibition catalogue and in a video accompanying the exhibition.

The principal difference between the projects is that Karkhana functioned as a closed system and Through Masters’ Eyes as an open one. But both projects, in their imaginative reconstruction of historical styles, involved the paradox of a collaboration that employed a kind of permutational logic to confirm the separation of participating artists. Both are examples of what Craig Saper has called “networked art”—“social situations that function as part of an artwork or poem.”3 (It was ironic that one network—the internet, with its digitized image of Shitao’s landscape—undercut the other network that Lee had so elaborately set up.) Most importantly, both projects may be seen as successful attempts to re-invent a non- Western contemporary art and insert it into that larger, Western-dominated network—the art world.

Through Masters’ Eyes, installation view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, May 15–August 1, 2004. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo (c) 2004 Museum Associates/LACMA.

At the recent College Art Association conference, the organizers of two panels— themselves associated with the Karkhana collaboration—sought evidence of other revivals such as calligraphy, silhouettes, ukiyo-e prints, and daguerreotypes that had also served as sources for contemporary art.4 They found instead papers about the reappearance of traditional approaches in postmodern ceramics and embroidered samplers; they heard about the re-circulation for various purposes of 19th century French Orientalist painting, traditional techniques in contemporary Iranian and Chinese art, and the iconography of Hindu images and African religious rituals. These varied instances that the panel presented seemed to be cases either of a postmodern recycling that flattened time so that everything became simultaneous, or a search for postcolonial identity. Due primarily to the historical context into which such instances have been received in the West, some of these instances appeared “exotic.” Several years ago the Turkish critic Beral Madra, who curated the first two Istanbul Biennials, commented that Shahzia Sikander was “orientalizing herself” by recreating the “old paradise” of the miniatures while living in New York—a tendentious remark, since the critic prefers art that deals more directly with political phenomena.5 Such considerations both do and do not appear relevant to the Karkhana and “Through Masters’ Eyes” collaborations, which are at once a homage to an illustrious past and its rebirth into the cradle of the contemporary art world and its market. Both series of works are compelling for their beauty and unerring authority of line and brush, and so—if occlusion has caused our recollection to be only partial—perhaps it is better that it stay occluded.

Michel Oren has published in Third Text; Callaloo, A Journal of African Diaspora Arts & Letters; and Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. For this review he would like to thank Jessica Hough, Terri Garneau, Anna Sloan, Murtaza Vali, Stephanie Barron, June Lomena, J. Keith Wilson, and Lee Mingwei for their assistance.

Hasnat Mehmood, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Saira Wasim, Talha Rathore, and Muhammad Imran Qureshi, Karkhana #9, 2003. Courtesy of the artists and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

Hasnat Mehmood, Aisha Khalid, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Saira Wasim, Talha Rathore, and Muhammad Imran Qureshi, Karkhana #12, 2003. Courtesy of the artists and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.