Tishan Hsu, Heading Through, 1984. Vinyl cement compound, ceramic tile, acrylic, wood, Styrofoam, steel, 39 × 82 × 60 in. Collection of the artist. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Upon entering Tishan Hsu: Liquid Circuit, the artist’s first museum survey in the United States, one encounters Autopsy (1988). The sculpture resembles a broad corporate office building shrunk down to human scale. Dusty brown tiles wrap around its smooth volumes, which follow the vacuum-formed logic of a hot tub or fridge. With the artist’s oversight, the sculpture’s modular layers may be swiveled one way or another on its central vertical axis to achieve its temporary resting position.1 A wide pink surface cuts open across the top plane and four pink columns protrude at each corner, with spherical stainless steel wheels dangling at their ends. Four more of these wheeled feet on the sculpture’s underside connect with the floor below. I imagine the entire object could be flipped horizontally and land just the same. The title of Hsu’s opener suggests that we consider the cause of death, presupposing that this being was once alive or that it is something in between: living but inert, or changeable postmortem. If what we approach here is an (abandoned) autopsy in progress, the viewer doubles as the imagined medical examiner.

The gridded tile that stretches across Autopsy is one of Hsu’s earliest materials, and it marks a bridge between his practice as an artist and his studies in architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1970s. (He moved to New York City at the end of the decade.) In Hsu’s words: “Tile has a gridlike quality that has implications in art history and is also related to my interest in the technological. There was no digital at the time. The tiled grid defines a surface, but I could build tile into forms, so the work could become an object seamlessly, going from gridded surface to organic form . . .” 2 Hsu’s Ooze works demonstrate this shift. Turquoise tile spreads horizontally and vertically, suggesting a portion of the lining of a swimming pool (as with the sculpture Ooze, 1987); it also wraps and stacks (Vertical Ooze, 1987), and reappears in smaller, sunken squares on the wall (Reflexive Ooze, 1987). This physical shift between surface and volume is also a cerebral one, wherein the grid describes form as information. The grid provides the basis for computational mapping, including of the body in a space. Tile is also a furnishing—in other words, a mediating surface between one’s body and architecture. These things converge in Hsu’s works to describe our involvement with the technologies we produce as humans and which, in turn, produce us.

Tishan Hsu: Liquid Circuit, installation view, SculptureCenter, New York, September 24, 2020–January 25, 2021. Left to right: Tishan Hsu, Closed Circuit II, 1986, acrylic, alkyd, Styrofoam, and vinyl cement compound on wood, 59 × 59 × 4 in.; Tishan Hsu, Vertical Ooze, 1987, ceramic tile, urethane, vinyl cement compound, acrylic, and oil on wood, 61 7/8 × 70 15/16 × 24 1/4 in.; Tishan Hsu, Ooze, 1987, ceramic tile, urethane, vinyl cement compound, and acrylic on wood, 137 ½ × 181 ½ × 68 ½ in.; Tishan Hsu, Reflexive Ooze, 1987, ceramic tile, vinyl cement compound, oil, acrylic, and alkyd on wood, 58 ¾ × 59 × 3 ½ in. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

If a survey show offers the opportunity to examine the progressions in an artist’s work over time, this exhibition does so in a deliberately bracketed fashion. Of the more than forty works on view in Liquid Circuit, around three-quarters were made before 1990, weighting the presentation toward the early period of Hsu’s output. His paintings made in the 1980s resemble bodies and faces pressing up against screens and bulging through them. One can imagine Hsu’s experience of being enveloped by computer-screen light as he worked evenings during this time as a word processor.3 By the end of the 1980s, Hsu’s art career reached a peak, with a succession of exhibitions at Pat Hearn Gallery and with Leo Castelli. In 1988, he moved to Cologne for two years, seeking a change of pace and place in which to focus on making art. Later works in the exhibition manifest his turn, at the onset of the 1990s, toward more flattened imagery that reflects the continued development of new screen technologies. The latest work on view, a video recording of custom software, was made in 2005. Hsu underwent a kidney transplant surgery in 2006, followed by a period of recovery and reorientation.

After the surgery, Hsu began referring to himself as a cyborg.4 But really, the cyborgian premise has always been present in his work. Software and machine learning evolved swiftly alongside Hsu’s concerns about the ways in which the human body and brain would be formatted imminently by and through technology. As the two increasingly coincided, Hsu made use of these new digital tools.5 In his own words, “The sensibility needed the technology. There has been a synchronicity that I did not expect.”6 Although the works in Liquid Circuit were made at least fifteen (and as long as forty) years ago, over and over I felt as if they had been made just this year, in response to the world they occupy today. A strange loop kept occurring in my mind, like I’d dropped off of the spacetime edge of Vertical Ooze only to land right back in front of it. Repeatedly, Hsu’s work performs a series of doubles, flips, inversions, and feedback loops, by design and well ahead of itself.

Tishan Hsu: Liquid Circuit, installation view, SculptureCenter, New York, September 24, 2020–January 25, 2021. Left: Tishan Hsu, Couple, 1983, oil stick, enamel, acrylic, and vinyl cement compound on wood, 66 × 48 in. Right: Tishan Hsu, Portrait, 1982, oil stick, enamel, acrylic, and vinyl cement compound on wood, 57 × 87 × 6 in. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

Entering the main gallery of SculptureCenter, two paintings hang perpendicular to one another: Couple (1983) and Portrait (1982). The works are rectangular with curved corners, and they float a few inches away from the wall. Both attributes are characteristic of Hsu’s paintings of the 1980s, which use supports like Styrofoam and cement compound on panel to build up their protruding surfaces, just as his sculptures do. (The sculptures hover above the floor like the paintings do from the wall.) To my eye, these curved forms read as descendants of the tarot card and precursors to the iPhone.7 Portrait displays the components of a face: two eyes and a mouth float disembodied within the frame. Between Portrait and Couple, Hsu’s mode of abstraction slips into sudden figuration, then slumps back again. Other works become more body-like in their material fleshiness, as the more obvious markers of the figure or face disappear. A colored glow emanates from the rear of the wall works that Hsu made in the second half of the 1980s, suggesting the transillumination of a screen or the drop shadow form that was beginning to appear in computer graphics at the time. Throughout the exhibition, the freestanding walls are curved at their upper corners, echoing the rounded edges of the paintings they display. The placement higher up on the walls of works like Portrait suggests a hidden or meta code for reading the work. In this configuration, the walls themselves act like screens upon which the works may be placed and continually rearranged, as if on a computer desktop. Hsu’s work describes the human body as both a fleshy, glowing being and as an icon shifting inside the screen.

At one end of the show, a grid of thirteen drawings, spanning 1980 to 1987, is hung in chronological order. Most are designated by their titles as studies for related works, including for Portrait and various others that appear in the exhibition. One drawing, study – continuous surface (1980), proposes a logically impossible object that stretches endlessly outward, over, and under itself, ricocheting in infinite lines that also make up a single form. Rather than serving as a sketch for a work to come, this drawing seems to diagram a broader concept (as indicated by its title) that plays out across Hsu’s paintings and sculptures. Around the corner, perched about two feet from the ground on a frame of four metal legs, the perimeter of Heading Through (1984) is rendered by hand in a thick, putty compound that is tinted a sickly greenish blue. A field of tiles makes up the remaining horizontal plane of the work. At one edge, this surface rises up a level to curl over onto itself, and a strange lump, which turns into a face, appears to grow on the back of its new edge. The other edge drops toward the floor. The surface textures and hues of Heading Through appear to seep into the nearby wall works Squared Nude and Plug (both 1984). Perhaps, then, Hsu’s “continuous surface” describes not only a structural device but also the activity that occurs both within and between Hsu’s works, as well as that between the works and their viewers.

Tishan Hsu, Heading Through, 1984. Vinyl cement compound, ceramic tile, acrylic, wood, Styrofoam, steel, 39 × 82 × 60 in. Collection of the artist. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Up close, Hsu’s paintings consist of many ultrathin lines forming fields of texture like hair that sometimes break apart to reveal dark voids behind them. Hsu explains: “To make a screen, I painted the surface and scratched lines into it. . . . It wasn’t a new technique, but it seemed to have the quality I wanted. I recalled making drawings by scratching lines onto a piece of paper through a layer of black crayon in grade school.”8 The effect appears most pronounced in R.E.M. (1986), the undulating surface of which seems to be visually mapping a person’s brainwaves during a sleep cycle (or two, as a second black space appears). But what is contained by these voids?

A 1983 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) document describes what it calls the Gateway Process: essentially using methods of hypnosis, transcendental meditation, and binaural beats to interact with and potentially program consciousness between the brain’s hemispheres. Following a great number of experiments (which find their foundation in the CIA’s earlier MK-Ultra mind-control program9), the study describes parts of the brain as computer software and reality as a “universal hologram”:10 “The universe is composed of interacting energy fields, some at rest and some in motion. It is, in and of itself, one gigantic hologram of unbelievable complexity. . . [T]he human mind is also a hologram which attunes itself to the universal hologram by the medium of energy exchanged thereby deducing meaning and achieving the state which we call consciousness.”11 By this description, the world as we know it is purely the result of information being received, processed, and delivered by the brain as image, heat, gravity, sound, and so on; thus all we really have access to or experience of is a “scrim.” Looking into the shadow spaces that lie behind Hsu’s loosening lines, we might be looking at a depiction of this very scrim and glimpsing the vast nothingness that expands just behind it. At this point, a sense of scale all but drops away, in the same way it might when trying to comprehend the vastness of outer space (which, really, might be much the same thing).

Tishan Hsu, Plasma, 1986. Acrylic, alkyd, oil, and vinyl cement compound on wood, 16 × 93 1/2 × 4 in. Collection of Daniel Newburg. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Jeff McLane.

Throughout, Hsu’s choice of titles—which pun and double—act as keys for navigating this invisible terrain. High above R.E.M. is Plasma (1986). The work is short, almost six times as wide as it is tall, and it speeds across the top of the wall like a red-and-yellow pill, glowing red from behind. In physics terms, plasma is one of the four fundamental states of matter and possibly the most abundant in the universe.12 It is associated with the sun and stars, both of which consist of plasma held together by its own gravity. It is basically a charged gas (although specifically not a gas) with strong electrostatic interactions. Lightning and neon lights are made of plasma, and plasma is used in manufacturing microchips and plasma TVs. Of course, plasma also refers to the liquid portion of blood, which constitutes more than half of its volume and is 92% water. The painting resembles all of the above: another continuous surface. The exhibition’s titular work, Liquid Circuit (1987), hangs at the heart of the space. At the center of its three conjoined yellow panels, three stainless steel grip bars stud the painting like the rungs of a swimming pool ladder, massive laces, or post-surgery staples.13 At either end, pushed apart from this center, an enlarged version of Hsu’s scratched-on screen motif reappears. At this scale, the lines that stretch across the voids could be those of sheet music, stitches, lasers, or the flickering lines of a CRT TV monitor. In these works from the latter part of the 1980s, the colors become more primary. A massive patch of red seeps across the four panels of Cell (1987) which, like Liquid Circuit, approaches an industrial scale. Given its title, we might recognize this as a red blood cell, and yet the work and word also speak to its modularity. A raised horizontal strip running across the center of each quarter approximates fluorescent ceiling fixtures, and again a potential shift in orientation occurs. (What if the work were to be hung from the ceiling?)

Tishan Hsu, Cell, 1987. Acrylic, vinyl cement compound, oil, alkyd, vinyl, and aluminum on wood, 96 × 192 × 4 in. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Jeff McLane.

In a trio of grayscale drawings—Dr. Hibbert screen module (1990), thermostat module (1990), and Dental screen module (1994)—shaded surfaces rise around curved rectangles that display representational images: a television character, a familiar wall-mounted device, and medical imaging.14 The works indicate Hsu’s evolving approach to screen media and the photographic image, as he shifted into a flatter, more clinical aesthetic by the beginning of the 1990s. Applying the same treatment to medical imagery as cultural referent, these works also point toward Hsu’s concerns about the development of technology and media in terms of biometrics, in which the body becomes data. Alongside Hsu’s earlier textured paintings and sculptures from the 1980s, which were informed, as Jeannine Tang describes, by “shifts in industrial and product design toward more ergonomic, minimal and user-friendly aesthetics,” these later works, now flattened against the wall, offer a doubled sense of the ergonomic as not only a question of industrial design but also as its own process of translation and transference of the body.15

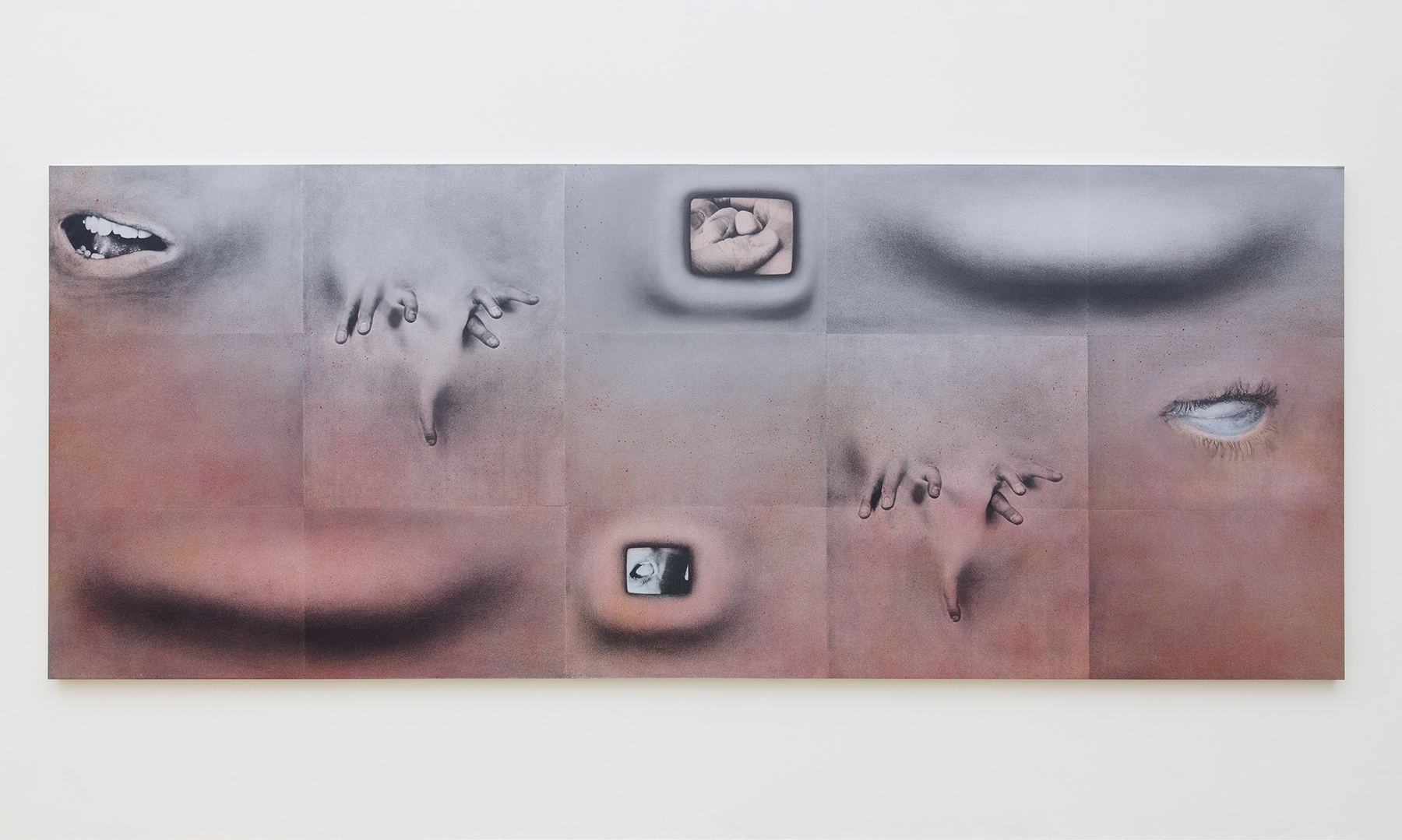

In Hsu’s words, “We’re all in the same boat with this problem of information and security.”16 The artist’s return to New York was marked by his 1989 solo exhibition Social Security at Pat Hearn Gallery, which included Cellular Automata (1989; a version of which is on view in Liquid Circuit) and Fingerprint (1989; not in the show). In order to emigrate to Cologne, the artist had submitted his fingerprints and a “certificate of good behavior” from his German-citizen peers.17 The prints found their way into Fingerprint, which incorporates a Xerox copy behind a gridded safety glass. Cellular Automata 2 (1989) is divided into nine squares that repeat or change, showing bodily elements broken apart through a fine mesh of screen-printed interference. An automaton is a “self-mover” (such as a machine) made in imitation of a human being, in whole or in part. For example, automata may be used to solve abstract problems (like a tic-tac-toe puzzle) by computationally mimicking the processes of the human brain. In another, billboard-like work, Fingerpainting (1994), photographic body parts repeat across a grid of fifteen silk-screened panes. An eye rolls back, a mouth is caught mid-speech, and smaller images of a mouth or toes appear within rounded rectangular modules. It’s as if, as time progressed and the image became clearer and smoother, the body pressing out from its surface became ever more entrapped within it, serving to extend the neurological limits of this digital field by pushing at its bounds rather than to free itself.

Tishan Hsu, Fingerpainting, 1994. Silkscreen ink and acrylic on linen canvas, 71 × 177 in. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Jeff McLane.

If the automaton is a machine made to be human, the cyborg is a human-machine whose capacities are extended through the use of “external” devices. Although rooted in sci-fi fantasy, the concept of the cyborg applies to virtually all of us today. (Hsu: “Google is my memory.” 18) When we find ourselves in a room looking at art, we almost certainly arrived here by relying on machine technology, which has come to rule the structure of our environments. And yet, the computational functions of these technologies cannot escape mimicking the processes of the human brains that created them. In this way, they are as much human as we are machine. The largest and most powerful algorithm in the world is one that you may have never heard of: Aladdin (Asset, Liability, Debt, and Derivative Investment Network). The algorithm functions through its massive computer server system to predict future world-changing events. Using this data, Aladdin is able to preemptively move trillions of dollars around so that those dollars, and the multinational corporate entities that own them, remain out of tragedy’s way by profiting from said oncoming tragedy. In doing so, the algorithm shelters the world’s macro structures from change in any fundamental sense. We now face the outperformance of the human brain by Artificial Intelligence (AI), which functions by machine learning, and beyond it lurks the encroaching problem of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), which hypothetically could learn or understand not only the specific tasks it is programmed to do, but also any other cognitive task, just as a human might. Hsu’s work manifests this drastic sense of scale and creeping invisibility.

What makes us specifically human, then, when our consciousness can be altered by external forces and will likely be superseded? (If we are cyborgian, by definition this requires that we be human too.) Hsu’s work performs in parallel to this question. As art, it insists precisely upon the material interface as the means for describing the overwhelming relationship between the body and the invisible fields and flows that form it. A kind of doubling occurs, as if Hsu were the one trying to replicate the human through available means. The only moving image work in the exhibition, Folds of Oil (2005), gives a visual and sonic mirage of familiar animal textures within a dark non-space.19 Here, it’s as though sound has a weight, or like the hidden being in the image (and in all of Hsu’s works) might finally, suddenly turn to look you in the eye. Perhaps what is really human is that which lies beyond or behind consciousness and its illusions. This returns us to the unknowability of all things, human and “non-human”—including the malevolent algorithm.

Tishan Hsu: Liquid Circuit, installation view, SculptureCenter, New York, September 24, 2020–January 25, 2021.

Foreground: Tishan Hsu, Autopsy, 1988, plywood, ceramic tile, acrylic, vinyl cement compound, stainless steel, rubber,

55 × 49 × 94 in. Background: Tishan Hsu, Interface Wall 2.0 – NY, 2020, from the series Interface Remix, 2002–ongoing, inkjet on vinyl on sheetrock, dimensions variable. © 2021 Tishan Hsu / Artists Rights Society. Photo: Kyle Knodell.

A leap in time occurs between Folds of Oil and the work that appears on the gallery’s entrance wall: Interface Wall 2.0 – NY (2020), a vinyl surface of bodily protrusions and orifices distorted by magnification bubbles and resembling an early Microsoft Windows screensaver. The work is a continuation of the series Interface Remix (2002–ongoing), and the only one revised the year of the exhibition. It bears relation to R.E.M revisited (2002), made sixteen years after its precursor. The painting is a flat inkjet on canvas split in two, producing a subtle horizontal line of shadow just above the middle. A soft visual reflection occurs within the image as well, where flesh conjoins flesh. The double becomes a mutation. One could consider the extent of machine learning as mutational as well, and so again Hsu not only intervenes but also mimics and alters from within the very processes that he addresses. In Hsu’s work, the surface, screen, or scrim is the place where consciousness touches the world. But what of the dust that lies on top of the paint, which sits between the surface of each work and that of my body, in person? Perhaps what makes me human is that I notice this dust and its shadow, and that I believe it to be evidence of a longer material memory, one which I can press into.

X—

Laura Brown is a writer, editor, and curator living in New York.