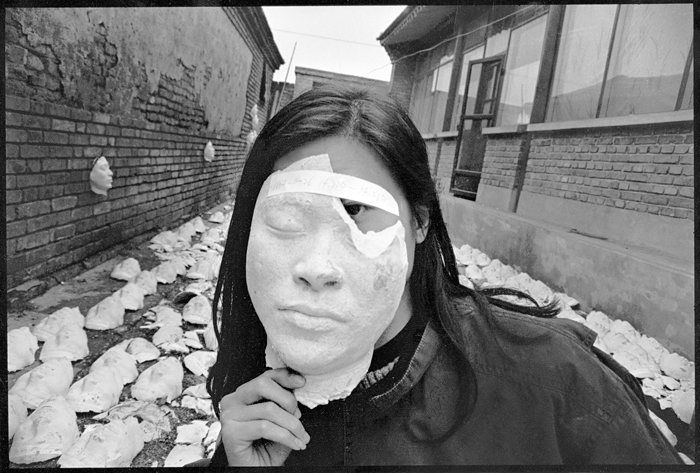

Rong Rong, East Village, Beijing, No. 70, 1994. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist.

Dear Mr. Ma,

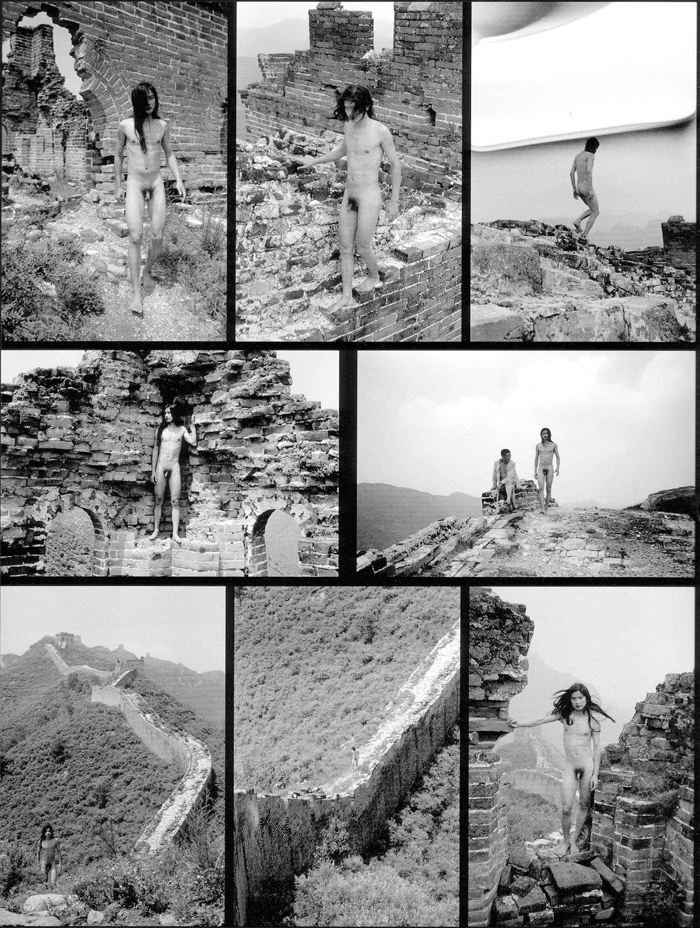

Although we are both contemporary artists of Chinese descent, we have never met. I am writing to you because I recently viewed your work Fen–Ma Liuming Walks on the Great Wall (1998)1 this fall in an exhibition titled Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China.2 In this survey of contemporary photography and video art from the People’s Republic of China, your work stood out as the only example of transgression across both the lines of gender and sexuality. In your seemingly endless walk on the wall, the contrast between your soft, feminized body and the rough masonry of the wall was striking. The Great Wall, of course, is one of the most enduring symbols of China’s national identity, a monument to militaristic power.3 Therefore, I find your choice of location very provocative. Even more so that you supposedly walked till your feet bled. Is this leaving of your bodily traces on the wall an allusion to the many who died building the wall—the poor laborers and the displaced rumored to have been buried along its base?

Speaking of references, were you also thinking about Ulay and Abramovic’s 1988 performance, The Lovers, 1: The Great Wall Walk? It was their last performance piece, you know. They started walking from the opposite ends of the Great Wall, and when they met in the middle, they said goodbye to each other and ended their relationship. Of course, in your performance, the male and female bodies have already met and become one. And as a Chinese artist, your presence on the wall connotes different meanings. I am interested in the many images I saw where you were literally “walking on the edge.” Your precarious balancing act made me think: on which edge do you balance yourself? The edge of gender? Of nationality? Culture? Or was it that edge of social acceptability that a contemporary artist living and working in China must face today?

Ma Liuming, Fen-Ma Liuming Walks on the Great Wall, 1998. Chromogenic print. Collection JGS, Inc.

I started thinking about your work when I was invited to speak on a panel about Between Past and Future by the Santa Barbara Contemporary Arts Forum. Since my work is not a part of the exhibition, and my research as a scholar does not focus on Chinese contemporary art, I suspected that I was invited because I was Chinese, an artist, and local. Agreeing to participate, I decided to use this as an opportunity to discuss the differences between overseas Chinese and Chinese in the PRC, and to highlight the complex experiences across the Chinese diaspora, which is a central subject in my current video work. In considering Fen–Ma Liuming Walks on the Great Wall, I thought it presents an interesting relationship to one of my videos, Movements East—West (2003).

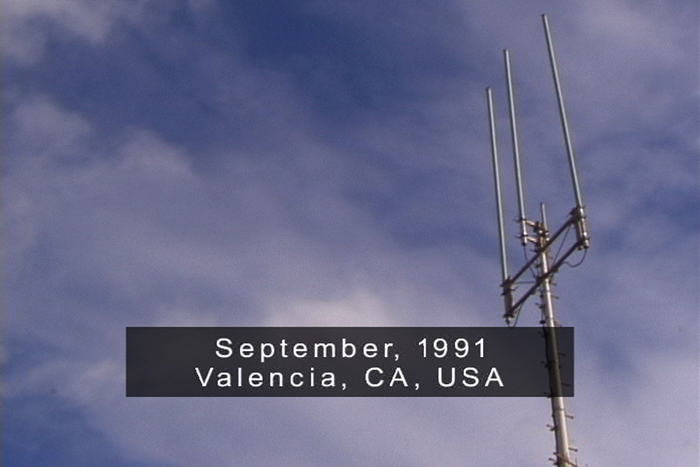

Movements East—West is an experimental video structured as a timeline of sixty dates and places, starting in 1841 and ending in 2001. In this timeline, my personal and family histories are combined with larger social movements and world historical events that have contributed to shaping my experiences. Like in Fen-Ma Liuming Walks on the Great Wall, the journey depicted in Movements East—West is not finite. Just as your seemingly endless walk on the Great Wall can be read as a metaphor of an on-going process — of identity formation, perhaps? — my journey in the video, and the various histories in the composite timeline, can also develop infinitely. However, while the body is very much present in your work, in mine it becomes deterritorialized. I remember the beginning of your video, where there is a brief but striking sequence in which you are seen putting on make-up. In my view, this is a literal “putting on oneself,” a process/performance through which you become Fen–Ma Liuming. I also remember reading about how you created this performance-art persona while living in the East Village, an impoverished artist community in Beijing formed in the 1990s, after the government crackdown of the Prodemocracy Movement in Tiananmen Square and the subsequent state persecution of artistic and other non-state-sanctioned means of expression.4 In Fen–Ma Liuming Walks on the Great Wall, the dislocation you are exploring stems from this transgender body you take on as a metaphor for the marginalized artist in contemporary China, and the tension created by juxtaposing your naked, feminized body with the monumental, militaristic Great Wall, a meeting marked by your blood left on its surface. In Movements East—West, the body of the artist is displaced, represented as a non-corporeal consciousness, a point-of- view that exists in tension with the historical specificity of the socio-political movements depicted. The Tiananmen Square Massacre of Prodemocracy activist was a defining moment for your generation. It is for me, too, but my experience of it was from afar, while for many of you its effects directly impacted your lives.

When I think about Chinese identity, the question I most often ask is “Which China?” Are we talking about the People’s Republic, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or the many overseas Chinese communities? I think more in terms of a Chinese diaspora than a motherland. For me, Chinese identity is always in flux— culturally, politically, and geographically. This might be different for you. I also think that our decisions to become practicing artists happen under significantly different conditions, as do the means through which we produce and distribute our work. As an artist in the U.S., I have access to technological and institutional resources that are unavailable to contemporary PRC artists. However, I also have to contend with the tradition and practice of a European and American art history, in which video and performance play very specific roles. Here, I am often considered an artist of color, a queer artist, whereas I would guess that you and your colleagues simply consider yourselves “artists.” Furthermore, for me, as a Chinese American who grew up in Hong Kong, there is always the ironic predicament of having to assert my “Chinese-ness,” which is not an issue for you, for whom “authenticity” is a guaranteed designation.

Ming-Yuen S. Ma, Movements East—West, 2003. NTSC/stereo/color/b & w/digital video, 17 minutes.

Speaking of identity and politics, it should come as no surprise that Fen-Ma Liuming is often read as a queer image, especially in the U.S. and in Europe. Although you had expressed that you “would rather pay more attention to the more abstract concept of sex and sexual ambiguity and indistinguishableness,” and that feminism and queer theory is not central to your work5, I wonder if that is even possible in contemporary culture, which China is rapidly becoming a part of in its modernization process. You said that you are interested in addressing the “abstract, ambiguity of sex.”6 In my experience, gender, sex, and sexuality are always political. What feminism and queer theory give us are alternative paradigms—the ability to discuss sexual politics while being conscious of the ideology of patriarchy and heterosexism. I think it is somewhat shortsighted, if not intellectually irresponsible, to not acknowledge how these cultural practices might inform the ways your work is seen in a global context. After all, you cited a meeting with the artists Gilbert and George, when they visited Beijing in 1993, as the “real origin” of your performance art.7 This tracing of a queer lineage in the engendering of your performance persona could prove a rich and fruitful direction for you. It could also help you to challenge the male/female gender dichotomy in China. Perhaps, some day, the separation implied by the “fen” in Fen-Ma Liuming will no longer be necessary, when you can embrace a more transgender politics in your thinking and in your performance work.

There is an image in the exhibition called East Village, Beijing, No. 70, (1994). It is by the photographer Rong Rong. This photograph documents a performance, Trampling on the Face, by Cang Xin, in which the artist made fifteen hundred plaster replicas of his own face, arranged them in his courtyard, and invited the audience to walk on the masks and destroy them.8 The photo did not show the process of destruction, but rather its aftermath. In it, one of the masks, partially destroyed, is held up in front of your face, while in the background the rest of the masks are visible. This is an intriguing image because it is an improvised collaboration between Rong Rong, Cang Xin, and yourself. The layers of representation—the framing of the photo, the casting of the mask, your partially hidden face—bring up the question of identity with an interesting twist. One is tempted to ask: “Will the real artist here please stand up?” This is further complicated when one considers: is this Ma Liuming behind the mask, or is it Fen-Ma Liuming? So behind the plaster mask is yet another mask. One could interpret these layers of masks as a commentary on the complex role Chinese contemporary artists play in China and abroad. However, there could be a problematic mirror-tunnel effect here, where reflection begets reflection ad infinitum. I happen to think that what is behind the mask, if we are allowed to see it, might be as intriguing as the masks themselves. As your career and the work of other contemporary Chinese artists become contextualized more and more in a transnational art world, I look forward to catching a glimpse of what is behind your mask.

Sincerely,

Ming-Yuen S. Ma

Los Angeles

7-27-2006

Ming-Yuen S. Ma is a Los Angeles-based media artist and Assistant Professor in Media Studies at Pitzer College in Claremont, CA. His experimental videos and installations, including Movements East— West (2003), Mother/Land (2000), Myth(s) of Creation (1997), Sniff (1997), and Slanted Vision (1995), have been exhibited nationally and internationally in a wide range of venues. More information about Ma can be found at www.mingyuensma.org.