To dissolve ourselves, our hermetic bodies, into the cosmic flow of all other matter is a familiar impulse. Today, it exists in a context where all living matter is absorbed into the global economy and has become capital itself. Technologies and scientific advances of late capitalism blur the boundaries between organism and machine. The fear of this assimilation is the fear of losing the self to capital and humanity to apocalypse, but Laure Prouvost, to quote Donna Haraway, makes “an argument for pleasure in the confusion of boundaries.”1

Laure Prouvost, A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek (detail), 2016. Installation view, Fahrenheit, Los Angeles, January 31–April 9, 2016. Photo: Deborah Farnault.

“Put your foot on the pedal, put your love in the ignition, you are what I’ve always been missing, you’re my petrol,” pants a mouth in breathy fragments in Prouvost’s Exhausted Video (2015). Anne Friedberg writes, “The windshield is the permeable membrane between Los Angeles and its screens,”2 but this membrane is stickily and seductively actualized by Prouvost’s exhibition A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek at Fahrenheit. Sex is not only human, and not only bodily, in Prouvost’s vision. In the central video work, A Lick in the Past (2015), five articulate, self-aware, and groomed young Americans lounge in a car, drive on the cement-coated Los Angeles River bed, and cruise into the burning sunset beneath palm trees. During this loose narrative, these protagonists of contemporary mobility copulate with technology and nature; mouths lick screens, dripping honey binds hand to iPhone, a squid smears its ink over the car hood, a fig sucks a nipple.

Milk, excrement, honey, and money elucidate flow in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s reorientation of the hierarchical relationship between subject and object to that of a rhizomatic web of interrupted and redistributed connections. The oil of this system is desire, or as Deleuze and Guattari name it in their shorthand collapse of fuel and engine, “desire machine.” “Doubtless there are those who will object that this mechanical, schizophrenic life expresses the absence and destruction of desire rather than desire itself,”3 but not Prouvost. Her protagonists imagine a slippery and libidinous union between machine and living matter. In four pencil portraits on paper, the first works encountered on entering the exhibition, exhaust pipes puffing smudges of smoke emerge from round, pursed mouths. A video of smoke is projected on one of the drawings, animating the puffs of the “smoker”; similarly, in Exhausted Video (2015), the seductive mouth is cut with shots of pluming smoke as it coos auto(mobile)-erotica. More than the pleasure Haraway anticipates, A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek is an unreserved embrace of the liberatory potential of dismantled categories. Prouvost’s work is staunchly non-didactic. But it’s useful to note that for Haraway the mission of material flow is feminist and decolonial: the patriarchal hierarchy of self and culture (man) above Other and nature (woman, colonized) is dismantled by a cyborgian confluence of human, animal, machine, and matter.

Laure Prouvost, Exhausted Drawing (Naomi), 2015. Pencil on paper, plywood mount. Courtesy the artist and MOT International. Photo: Jeff McLane.

“I’m going to lick the petrol, I’m going to lick the cracks that are right down the road,” whispers a voice as the young protagonists of A Lick in the Past, awkward in their self-consciousness, constantly create themselves via the screen, in a love act with the screen, all the while coyly, jokingly, tenderly talking of licking another’s eye, entering mouths, and sucking on breasts. The long entrenched analogous relationship between cars and sex, and more generally the modernist bond between machine and desire, renders imagery of the amateur actors in A Lick in the Past caressing a car chassis familiar enough. But the consummation of that desire denotes a more contemporary collective ambivalence toward becoming machine in which the subject and object are dissolved into one. “The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence,” writes Haraway.4 This ambivalence, the apocalyptic and utopian duality of becoming cyborgian that is so palpable in our relationship to technological advances, is present in the conflicting words of the young stars who at once lust for and revile technology and in our own tactile pleasure of the post-apocalyptic installation. Like encroaching sea levels or geological stratification, blue resin, rippled with the waves of its successive layers, coats the floor of Fahrenheit and paint streaks the walls like watery run-off. Embedded in the resin are fragments of current technology—keyboards, iPhones, charging cords—as well as natural materials; clusters of eggshells, foliage, and feathers. In the center, two car seats and an industrial side table with office phone provide a corporate-cum-Mad-Max-style vantage point for Lick in the Past.

Prouvost confuses the space of the moving image and the installation, tangling fictive space with physical reality. This immersive quality is crucial to Prouvost’s practice and is often enacted in multiple ways simultaneously, creating synesthesia. She has been known to hand out raspberries to audiences at her lectures, citing an important influence of hers—the celebrated Austrian filmmaker and poet Peter Kubelka.5 Kubelka uses the example of the raspberry to explain mnemonics; the sublime sensation of first eating a raspberry lodges in a child’s unconscious and becomes the standard, recalled and compared to every raspberry tasted thereafter.6 The legacy of Kubelka’s structural films can be traced in Prouvost’s erratic, sometimes almost abstract visuals, and the power of mnemonic synesthesia is consistently present in her work. The moving image, triggering multiple senses at once by creating associations in the unconscious, is the agent of seduction in works such as Swallow (2013). A pastoral audio-visual montage, it features a fish mouthing wet raspberries, underwater gurgling, an orange being split, cicadas chirping, lips opening and closing, deep breathing, and a voiceover cooing “this voice is the sun touching your face” and “the rocks are naked.” Prouvost encourages a visceral subjectivity through mistranslation of sentiment into sound, vision, language.

Laure Prouvost, A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek, 2016. Installation view, Fahrenheit, Los Angeles, January 31–April 9, 2016. Photo: Jeff McLane.

This active, synesthetic, and mnemonic potential of translation and mistranslation in Prouvost’s work occurs between forms and mediums, between senses, between subjects, and between English and French, but more importantly between word and image. The malleable potential of language is the constant in A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek. Questioning the validity of language’s ability to hold meaning, in the manner of Jacques Derrida, Prouvost uses language as audible words or visual text. On first encounter, her text works—in the form of small black oblong canvases painted with white sentences—seem bafflingly concrete, like remnants of an abandoned conceptual practice. Stark and droll, they depict sentences such as “Ideally this room would be square,” and “Ideally this corridor would never end.” In Prouvost’s hands, such simple statements become absurd rhetorical strategies for destabilizing meaning. Absurdity is that which arises in the space between apparent meaninglessness and our earnest search for universal order; why can’t I make sense of this non-ideal situation? The solution, Albert Camus tells us, aside from suicide or religion, is to accept the absurdity, which Prouvost does with enthusiasm.7 The biography provided on the room sheet for A Way To Leak, Lick, Leek tells us she was born in 1961 in (fictional) Uhnreka, USSR, and lives in a trailer in the Croatian desert.

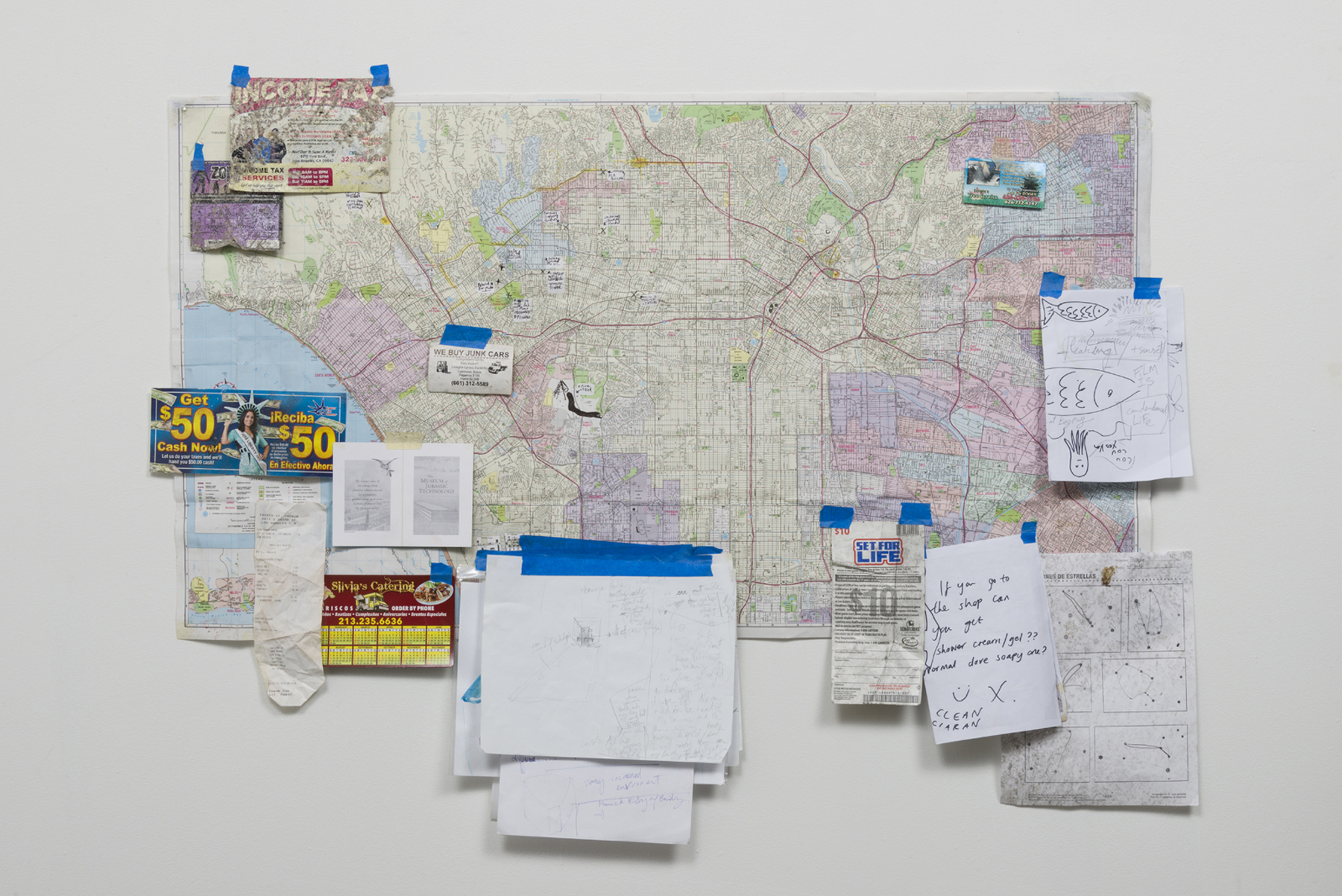

Dismissing stability of identity, self, or essence, Prouvost fictionalizes herself and her characters indiscriminately in her work. Just as science fiction attempts to liberate characters from the shackles of oppression and the limitations of the present, so too Prouvost imagines new situations not as fantasy but as a speculative space for creating reality. Her 2013 Turner-Prize-winning exhibition Wantee gave us her conceptual grandfather, who is reportedly a dear friend of Kurt Schwitters and mysteriously missing. In an easy to overlook video playing on an iPad that is trapped in the resin spill of A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek, we are introduced to a young man in a tawdry office. Fondling dollar bills and scanning a laptop, this entrepreneur of the new world talks of seeking oil, as has been the Californian story for over a century. Behind him, tacked to his office wall, a postcard gibes, “Doin’ business California style.” In the gallery, a map of Los Angeles is framed by the kind of flyers that drift through car parks, announcing, “Win $50 Now!” “We buy junk cars,” and “Income Tax; let us help you this year.” These are the ferocious and desperate words of the get-lucky-or-die-trying brand of capitalism that resulted in 44,000 homeless people in Los Angeles County on any given night in 2015.8

Laure Prouvost, A Way to Leak, Lick, Leek, 2016. Vinyl tiles, resin, various electronic items, paper sheeting, iPads, iPhones, tablet screens, foliage, metal, plastic, wood, cables, polyester seats. Commission: Fahrenheit by FLAX. (Background) Lick in the Past, 2016. Video, 8:23 min. Courtesy the artist and MOT International. Commission: Fahrenheit by FLAX. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The paper map, bearing the fold lines of the kind people once kept in their glove boxes, is marked with locations of oil sites amongst Los Angeles’ residential and business neighborhoods. Oil—liquid capital of the earth—is, of course, now synonymous with the progress of the twentieth century. Prouvost’s map, dotted with pump jacks, images the earth as machine itself. In a strangely close paralleling of Prouvost’s aquatic-automotive associative web, on the site of Los Angeles’ first oil well now sits the present-day Echo Park Deep Pool parking lot. Drilled in 1892 by Edward Laurence Doheny, it was the subject of Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel Oil!, which was later adapted into the film There Will Be Blood (2007). The speculative business of entertainment delves back in time to meet the speculative business of oil drilling.

Laure Prouvost, Exhausted Map, 2015. Various Materials. Courtesy the artist and MOT International. Photo: Jeff McLane

Fiction and oil are entwined in Los Angeles, not only in film but also in their very physicality.9 Oil wells hidden in plain sight, some of which are marked on the map in Prouvost’s installation, dot the urban landscape. Crude is extracted at Beverly Hills High School, where a derrick, named the Tower of Hope, is shielded with a skin painted by 3,000 children from local hospitals. This stranger-than-fiction scene was the setting for “Beverly Hills 90210,” the television show that painted an idealized picture of teenage life in Los Angeles for the rest of the world. Although the specifics of oil or film history are of no particular importance to Prouvost’s more immediate, experiential installation, the long-time relationship between the filmic image of Los Angeles and cars, and the fuel that runs them, are responsible for the tropes that Prouvost manipulates in the teenage road narrative of A Way To Leak, Lick, Leek. Drawing attention to this slipperiness and the fallacy of narrative, Prouvost delights in such tropes in her work: the bucolic Italian brook is populated by nymph-like women in Swallow (2013), tea-obsessed grandparents dwell in the English countryside in Wantee, and, in Lick in the Past, Europe is depicted as green fields spotted with castles, cows, and moped riders.

Prouvost pours the holographic, deceptive metaphor of oil across this exhibition. While the narrative of oil seems like a relic of frontier California, petroleum still literally keeps Los Angeles functioning. As gas prices bounce up and down, the micro-economic impact of international maneuverings is felt in the quotidian movement of Angelenos. Ripples are not distributed evenly, of course. Transport in Los Angeles is racially divided; 90 percent of public transport users are people of color, while the hermetic sphere of the car reinforces the violent individualism that allows other citizens to avoid any sense of collective responsibility for social life.10

“I’m about to drive in the ocean,” sings Frank Ocean in his 2011 single “Swim Good,” which repeats throughout the Lick In The Past soundtrack. Ocean’s track is still a regular on mainstream Los Angeles hip-hop radio stations and, like most West Coast hip-hop, sounds best when you’re driving on a freeway. The mesmerizing horizon, soporific heat, and endless curves in the road are paralleled by the hypnotic pace of G-Funk, a kind of Gangsta-Rap that originated in Los Angeles in the 1990s and has impacted the stylistic trajectory of rap and hip-hop on the West Coast ever since.11 While this mood and the refrain of Ocean’s song is thematically on-point for the Californian road-scene of Prouvost’s video, the rest of his lyrics point to a self-annihilation in an escape from “something bigger.” Ostensibly a tragedy of unrequited love, Ocean’s track might also be understood as a refusal to endure America’s contemporary crisis: the murder of black men and women. That is, of course, one of the true stories of Los Angeles streets. On these streets, cars are often places of crimes against citizens, but also the means for self-determination and agency, and where West Coast rap is shared as a tool for recording and resistance.

Prouvost’s flippant citation of tropes, including the geographic and historical specificity of West Coast rap, contributes to a specious vision of Los Angeles. Nevertheless, A Way To Leak, Lick, Leek, although not adequately encompassing the violence and poverty of contemporary Los Angeles, does point to the liberatory space of speculation and crucially reinforces the importance of bodies. The cyborg, Haraway argues, is “a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centres structuring any possibility of historical transformation.”12 Here Prouvost allows us to haptically experience the importance of desire and fiction as productive forces for creating new realities.

Pip Wallis is a curator and Associate Managing Editor of X-TRA.