Summer group shows tend to function a bit like curatorial Muzak for the art world. They are innocuous, low-risk ways to fill space while curators and gallerists take the summer off. Drama of the Gifted Child: The Five Year Plan at the Armory Center for the Arts annihilates this paradigm like an indie release of a superb grunge-punk-rock-ballad. David Burns, former assistant curator at the Armory and an artist (best known for his work with L.A.-based collective Fallen Fruit), assembled this impressive and atypically cohesive exhibition from a selection of Southern California art school graduates, all of whom received their MFAs in the last five years.

The show takes loosely as its premise Alice Miller’s 1980s pop-psychology book The Drama of the Gifted Child, which sought to explain the identity crisis of kids who comprise Generation X:

…[T]he child who was so aware, consciously or otherwise, of the wishes of his parents and had such a strong desire to fulfill them…lost track of himself and his own identity. It’s about the child who never discovered his “true self” because he was so concerned with pleasing those around him, and the repercussions of that later in life, as an adult.1

This seems like an odd, and possibly even unflattering, context in which to place contemporary artists. One wonders who (or what) occupies the role of the proverbial parent who has inadvertently fostered such sycophants. The Gallery? The Collector? The Critic? Art Schools? The Market? The Art World as a whole? Add to this dilemma the struggles of making art and finding one’s identity in the post-9/11 world, post-art-market boom, and post-postmodernism, and you really have a challenge on your hands. The artists in the show present some provocative solutions to the difficulties of making work in the current era of a globalized, decentralized art world. Their works share elements of humor and collage, which are frequently used in the service of hopeful, ontological inquiries into the role of the artist, the use of materials, and the layering of meanings. The press release claims that each artist’s work evidences a negotiation between studio practice and the art market. But the finished pieces in the exhibition do not necessarily offer insight into the artists’ processes, and there are few indications that the art market and marketability are central concerns for this group of artists. (Marco Rios’s refusal to list the works of his that weren’t for sale on the exhibition checklist is the exception.) Frankly, I wasn’t feeling too much sympathy or interest in this solipsistic conundrum upon first approaching the show. While Miller’s eponymous book may provide a temporal and cultural seedbed for this generation of artists, the relationship of the work in the show to the book’s premise is not made clear. Other points of interest do emerge, however, that make for a rich and compelling exhibition.

That all of the artists participating in this exhibition are very recent graduates reflects the current state of the Southern California gallery scene, in which recent MFAs from favored programs are doted upon in galleries’ desires for success and notoriety. The producing of Kunstwunderkind under this system is a phenomenon that was propagated, in fact, by the rise of MFA programs in the 1980s, which is the same era as the publication of the titular book. The art market boom in the 1990s resulted in a spate of shows of recent MFAs, which too often seemed to assert the alleged genius of the pathetic aesthetic—that late 1990s/early 2000s grunge aesthetic that yields flimsy sculptural installations comprised of tin foil, Styrofoam, balsawood, trash, and hubris. Such work is regrettably uninformed by its more politically substantive predecessors (including New Realism, Arte Povera, Art Brut, scatter art, and the informe). While grunge did interesting things for music and fashion, it was not good for the art world.

Drama of the Gifted Child: The Five Year Plan presents a welcome antidote to the hurried and superficial work of the pathetic aesthetic era, and instead offers a dectet of artists with complex and compelling practices that together propose a vision of optimism for art in the post-everything era. Their work presents polyvalent semiotic rubrics, well- crafted media, and conceptual foundations that acknowledge their postmodern forebears but also present well-considered innovations. Also notable is that this show did not include a single painting on canvas, but rather featured mostly videos and installations—genres most often overlooked in the gallery circuit.

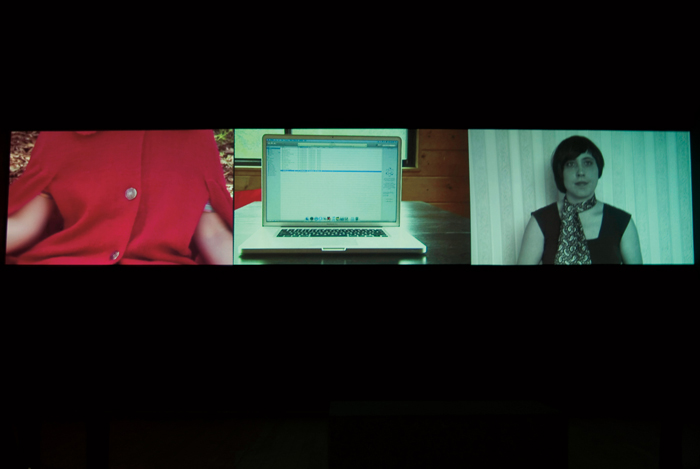

Julie Lequin, Top 30 (en 3 temps), 2009. Video, 13 minutes 51 seconds. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Primo Catalano.

The theme of the exhibition is best exemplified by Julie Lequin’s video installation Top 30 (en 3 temps) (2009), which is the most directly narrative and self-reflective work in the show. Spanning the width of a wall, Top 30 presents three videos projected side by side, each with audio that complements and overlaps with the other channels. The piece charts the three years leading up to Lequin’s 30th birthday as she contemplates personal, artistic, and societal expectations of a woman of her age. In one channel, Lequin delivers a poetic, psychological distillation of each year as she holds up playful watercolor illustrations to accompany her narrative. Her voice sounds young, lispy, and naïve, yet if you listen closely for long enough it’s clear from her diction and vocabulary that she’s a crafty, sophisticated storyteller. The middle channel features a corresponding sequence of three machines that play music—record player, radio, and laptop. The third channel features black-and-white clips of individual women, including the artist, standing against patterned wallpaper. One woman sings an anthem, another looks silently into the camera, and a third sings an emo pop song a cappella. While watching this collection of videos, what at first appears quirky and esoteric comes to seem philosophical and poignant.

Forming a different category of work in the exhibition, Dan Bayles and Kelly Sears amass and organize information, and repackage it into aesthetic systems. Bayles’s installation Hypergraphia (2009) fills a wall with overlapping, pinned-up pages of various ephemera—drawings, photos, manifestos, graphs, and diagrams—which function like a real-world bookmark bar. The kinds of information that the images track—weather patterns, weapon designs, rockets, kites, evidence of aliens, and military plans—infer a conspiracy theory. The project provides no conclusive proclamation but offers instead a warning or prophesy of sorts. As a rhizomatous index, it alludes to the dissemination, collection, and reorganization of information to feed or quell anxieties.

Kelly Sears, The Body Besieged, 2009. DVD, 4 minutes 30 seconds. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Primo Catalano.

Sears’s video and two sets of mixed media photo-collages also recompose information. Each proposes a temporal collapse by using contemporary digital media to fuse dated, black-and-white, half-tone photographs with old school, digital graphic backgrounds. Her video The Body Besieged (2009) animates photos of women from a 1980s aerobics how-to manual against a pulsating background of alternating geometric patterns and textures. An industrial, electronica beat thumps in sync with the background texture. Akin to a Hans Richter film or Lázsló Moholy-Nagy photo-collage, Sears presents these figures in decontextualized formal environments. Her compositions utilize strong diagonals, high contrast, and disorienting perspectives. The women’s bodies grow and shrink in an infinite matrix reminiscent of Bauhaus aesthetics.

Another group of works in Drama of the Gifted Child embraces elements of horror, enigma and the macabre. Julie Orser’s video Blood Work (2009), for example, extracts quintessential visual and aural elements of horror films. One by one, archetypal props (teddy bear, high heeled shoe, lampshade, purse) are doused with bright red fake blood as familiar horror movie melodies and Foley effects amplify the drama. The scenes are inter-cut with images of the perpetrator, who dons a white janitorial suit and ineffectively mops up the pervasive red liquid. The iconic and succinctly paired images and sounds stand in for our psychological projections and sublimations. In its camp indulgence, the video alternately elicits shock, laughter, and uneasiness.

Rios’s suite of photographs and sculptures fuse food imagery with gore. Laminated images in which body parts and hunks of human flesh are Photoshopped into pseudo-gourmet delicacies with names like Heather Weiner Leg (2009) sit atop color-coordinated pedestals. These campy visions suggest what you might find on the menu in a greasy spoon run by Hannibal Lector. The images contain obvious visual and linguistic puns that seem superficial when compared to their sculptural counterpart—Untitled (Pacific Dining Car, Filet Mignon; Ruth’s Chris, Porterhouse for Two; The Pantry, Tenderloin) (2008). This set of beautifully fabricated, stainless steel casts of big, fat, juicy steaks at once literalizes the fetishization of flesh and points to the oft absurd indulgence and waste that results in the pursuit of culturally valued artifacts. One wonders what a Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles dinner might look like in bronze.

John Knuth, Spencer Douglass, and Bari Ziperstein investigate entropy, appropriation, and decomposition in their works (respectively). Knuth’s installation Sugarland (2009) consists of a ton of sugar piled in snowy heaps in the middle of the gallery floor. In a nod to art history, the piles recall earthworks, scatter art, and conceptual art. Sugar, like salt, is a substance with many allegorical possibilities in both its form and history. On the wall above the piles, eleven box frames encapsulate granulated sugar. Caramelized blobs of sugar reflected in the gold background of the frames allude to abstract expressionist forms. Provocatively placed adjacent to Rios’s steaks, Sugarland calls to mind the wastefulness of an affluent society in which consumables are freely sacrificed for artistic experimentation.

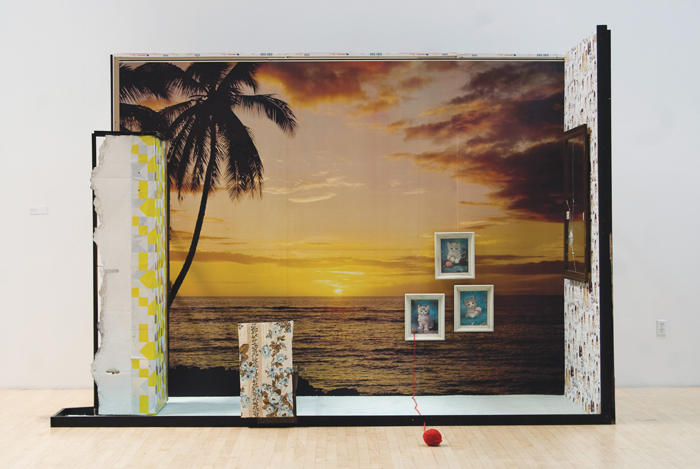

Spencer Douglass, Montana, 2009. Mixed media, 8 x 11 x 4 feet. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Primo Catalano.

Douglass’s Montana (2009) is a rare example of compelling installation art. Like good poetry, it presents a carefully selected arrangement of forms that is comprehensible and substantive upon first read, but also offers continued discovery and satisfaction upon subsequent readings. Montana is a mixed media installation much in the spirit of works we’ve seen before by artists such as Jessica Stockholder and Gedi Sibony. Douglass takes inventory of recent, familiar sculptural trends—including using deconstructed building materials, soothing photomurals of natural settings, and thrift store paintings of kittens (kittenkitsch)—and forms a sculptural dissertation on all of them at once. Douglass pits the formal elements of his materials with the kitschy implications of signifiers such as a sunset photomural, stickers on a broken mirror (“I heart Grandma” and “I heart Grandpa”), and a sea-foam blue carpet in which a small figurine fishes. His carefully calculated formal decisions and the inclusion of narrative elements lift the installation above categorization as pathetic aesthetic sculpture. The deal was sealed for me by the Eva Hess-esque ball of red yarn that rolls right out of one of the kittenkitsch portraits and onto the middle of the gallery floor.

Bari Ziperstein, Carmel, 2009. Altered slip cast earthenware and inlay, finished with low fire glazes, gold luster, and electrical. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Primo Catalano.

Ziperstein’s sculptures could have resulted from a dinner party at the Bauhaus where Salvador Dali, M.C. Escher, and Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel sat at the table together. Ziperstein deconstructs found ceramic figurines and combines them with other found figures and alien shapes, so that a polygonal form might extend a torso, or a light bulb might replace a head, or a tassel hang in place of pubic hair. The hybrid forms are then recast and meticulously finished to resemble their original kitschy sources.A menagerie of these chimeras populates a mass of similarly reconfigured pieces of furniture. If art is at times to provide us with visions of a potential, hypothetical reality different from our own, it isn’t bad to imagine encountering one of these in a thrift store and envisioning a moment of French Romanticism gone fantastically, surrealistically awry.

While I’ve broken them down into sub-themes above, all the works in the show share elements of humor, collage, and self-conscious kitsch. Each artist layers ideas and materials to create works that are aware of their visual and structural predecessors. What intrigues me is that these artists offer works that seesaw between being sincere and snarky, as if these “gifted children” are trying to find their place in the (art) world. The many succinct and polished pieces offer playful, well considered explorations into content, material, and self-awareness that are inspiring. For the first time in a while, I walked out of a show feeling optimistic.

Micol Hebron is a video and performance artist based in Los Angeles. She is an assistant professor of New Genres at Chapman University and a founding member of the LA Art Girls. She came of age in the 1980s, in the twilight of hippiedom and the rise of the yuppie.