“What bothers me about de Duve’s Kant After Duchamp (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998) is that in such an informed and believable analysis he doesn’t much acknowledge the sexuality inherent in the Readymades, …I do not know if it is because another model of interpretation is problematic for him within the framework of an “archaeology of pure modernism” and/or that the subject of “desire” is off-putting because it admits to psychoanalysis…”1

As we all know, everything can be interpreted sexually. But, at least as pronounced by its originator, Freud, this hypothesis does not mean that everything can be seen as a metaphor for sex. For Freud, especially as (re)interpreted by his follower Lacan, what is at stake here is not penetrative sex, but human intercourse—interpreted in the widest possible sense—which is always (in)formed by an element of desire. This, not carnality, is what the Freudians mean by “sexuality.” The point is that, unlike sex, sexuality and desire are the index of an individual’s unique relation to an “object,” and hence to the external world. In other words, the hypothesis that everything can be interpreted sexually simply means that there is no such thing as absolute “objectivity,” for every perspective is at least partially in- formed by the unique I/eye of the one who is looking/speaking. The work of Nicholas Lowie and Sheridan Lowrey reminds us that one of modern art’s aims is to keep this fact firmly before us.

Lowie and Lowrey work as a team. They see with double I’s, aiming less to undermine the “archeology of pure modernism,” than to complexify its logic by uncovering the layers of allegory woven through even the most formalist and conceptual modern art. Their argument is manifest in both their visual work, shown this summer at Track 16, and in their writings, published simultaneously by Smart Art Press. The book is not an explanation of the show, nor were the visual pieces mere illustrations of the theses outlined in the texts. Like their creators, they work together.

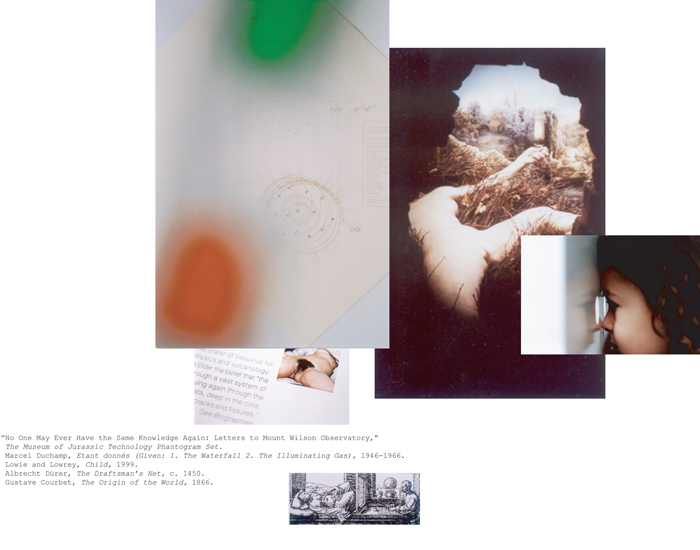

The show, entitled One-Hundred-Sixty-One- Year Exposure/ One Hundred Twenty-fifth of a Second Exhibition, comprised eleven different pieces, from video and video-installations to photo-collage and diagrammatic wall drawings. One entered through a narrow passage whose walls featured the video projection of a “wedding in which the bride (the Corinthian Maid/Butade’s daughter, Jocasta, Eurydice, Madalena Delani, Jacqueline Bouvier) projects her groom: a man walking past the Louvre’s crystalline pyramid.2

Thus the title of the exhibition, “One- Hundred-Sixty-One-Year Exposure/One Hundred Twenty-fifth of a Second Exhibition” points to photography’s (and cinema’s) articulation of “illogical conjunctions” of space and time…. “One-Hundred-Sixty-One-Year Exposure” refers to the time, counting back from the year 2000, since the/a first photograph.3

The second half of the title, “One Hundred Twenty-fifth of a Second Exhibition,” references numerous modern theories of and practices involving the study of time, from Muybridge and Cartier-Bresson, to Husserl and, of course, Duchamp. On this reading, the eleven distinct installations, and the totality they compose, used photographic images, and the apparatuses that produce them, to explore the history of photography and the theorizing it has inspired. The purpose, however, was not so much to construct a thesis about photography as to explore how modes of understanding and the critical reception of art have been (in)formed by modern technology, and to suggest an “ethics of cognition” relevant to the now. We begin to comprehend what this means if we look at the work from its other side: the duo’s book.

Illustrated with copious diagrams and other technical visual apparatus, Pinspot #14: Nicholas Lowie and Sheridan Lowrey, [A] Rrose is an apple is an artwork in its own right.

With an introduction by the LA Weekly’s beloved critic, Doug Harvey, this slim volume introduces the pair’s ongoing investigation into the hermetic correspondences between the work of Marcel Duchamp, the paintings of Gustave Courbet, and the Los Angeles institution known as the Museum of Jurassic Technology. In five short essays, Lowie/ Lowrey assert both the existence of a here- to-fore undiscovered theme in Duchamp’s work, and that the MJT is the means by which they have “discovered” this fact.

Lowie/Lowrey’s texts suggest that the MJT plays the role of precedent for a body of works that were conceived well before it. [They] (and/or the MJT?) have, in effect, created a hybrid/ a duck-rabbit/ a Lincoln-Wilson that belies usual historical lineage… .4

Refracting Duchamp’s oeuvres through the MJT, Lowie/Lowrey’s project functions as an alternative to the formalist and conceptualist interpretations of modern art history. Under this new interpretation, the Museum is not merely one of Duchamp’s many heirs, it is his principal predecessor, exploring avant la lettre the themes and strategies we now associate with the founder of “conceptualist” art. These include the question of artistic authorship and authority, the “infrathin,”5 the relations between (philosophical) aesthetics and science, the transmission of information and the part played in this process by sensual appeal, game-like attitudes towards the spectator, ultra-cross-referentiality between the different parts of the project, and a supremely serious, albeit exquisitely framed, attitude towards their own agendas. Contrary to many contemporary sensibilities, irony is never in play here, not in Duchamp, not in the MJT, and certainly not in the work of Nicholas Lowie and Sheridan Lowrey.

To this list of correspondences, Lowie/ Lowrey have added another: allegory. In their eyes, the Museum of Jurassic Technology reveals Duchamp’s work as more than just a set of formal strategies aimed at promoting anti-visual views of art. It also embodies a distinctly representational level in which both the biblical narrative of the Fall and the “science of morality,” as previously formulated in kabalistic Trees of Knowledge and Life, are constantly reappraised through the Bride and Her Bachelors, the figures of the “one-flesh” of the apple (tree). In “Muttum,” the third essay in their book, the artists ask: Is it too overwhelming to…assert that the mysterious “Lower Jurassic” on which the Museum of Jurassic Technology bases its contents is the Bachelors’ Domain of the Large Glass?6 The overarching theme of Duchamp’s work, from this perspective, is the re-presentation of the narrative of Being and Becoming as told in Genesis. Lowie/ Lowrey’s point here is not that we should replace the formalist reading of Duchamp by an allegorical one, but that (t)his work can only be understood when we place the two together. Indeed, the proposition that we both can and should look at modern and contemporary art as formal-allegorical duck-rabbits is the nodal point round which all their multi-media complexes turn. This is what the artists mean by an “ethics of cognition,” the deliberate act of looking with two eyes at once, a formal “I” and an allegorical one.

To many, this use of the MJT as the cipher for an interpretation of Duchamp is untenable. Such disdain is exacerbated when the pair reveals that the essence of the code is sexual. An hilarious, or mortifying, moment—depending on your attitude—was produced at a Track 16 panel when the artists suggested that the Center for Land Use Interpretation, which they see as a membranous portal to the Museum, called for public acts of jouissance7 when it sited at a bus-stop a sign saying, “Get Off Here.” To many, this use of beloved, and clearly not-sex obsessed institutions, for the development of a private thesis, is not only mad, but irresponsible, even unethical. Though I have some sympathy with this view, it seems touched by a proprietary attitude that, to me at least, sits uneasily with the MJT’s ethos. There are two parts to this objection. First is the inappropriateness of using one (artistic) production to interpret another, or just plain using someone else’s work as the raw material for your own, when their/your aims have nothing to do with the original authors’ intentions. Second is the apparent absurdity of seeing both Duchamp and the MJT as primarily concerned with “sex.” As I shall show, these two are linked.

Delire

“My ideal library would have contained all Roussel’s writings—Brisset, perhaps Lautreamont and Mallarme. …This is the direction in which art should turn.” (Marcel Duchamp, “Painting…at the service of the mind,” 1946).8

We have already seen that, like Freud, the stake for Lowie/Lowrey, is not sex but sexuality, i.e., desire as the index of each individual’s unique attitude towards the(ir) “object” and hence to the external world. To understand how this can be linked to the appropriation of another’s work, we need to consider not just desire, but what the French call delire. The word delire has no direct or neat translation in English. The literary theorist Jean-Jacques Lecercle provisionally defines it as “a perversion which consists in interfering, or rather taking risks, with language.”9 Though the delirious may use language poetically, they regard it primarily as a substance in which the Truths of the world are embedded. The most famous artist of delire is Jean-Pierre Brisset (1837-1923), an amateur philologist and logophile who deduced from his linguistic studies that Latin never existed as a real language, and that man is descended from the frog. In 1912, he also enjoyed an ephemeral notoriety, when, as the result of a hoax orchestrated by Jules Romains, he was proclaimed French “Thinker Laureate,” well ahead of his one rival in the ballot, Henri Bergson. The irony, as Lecercle points out, is that Brisset’s work has fared much better than most of the “serious” writers who sought to make fun of him. Breton, Foucault and Deleuze have all written on Brisset, and recently his entire oeuvre was reissued in a handsome volume with accompanying essays by his many admirers.10

“His method is now well known. It is etymology gone mad. The revelation that God confided in him and that enabled him to make his astounding discoveries is that the history of mankind is contained in language, that etymology does contain the truth, not only about the word, but about the world.”11*** Lecercle, Philosophy Through the Looking- Glass, p. 16.*** The core of Brisset’s delirium is that “all ideas with similar sounds have the same origin and all refer, initially, to the same object.”12

One virtuoso demonstration of how this law worked runs as follows:

Les dents, la bouche.

Les dents, là, bouchent.

Les dents la bouchent.

L’aidant la bouche.

Lait dans la bouche.

Laid dans la bouche.

Laides en la bouche.

L’aide en la bouche.

Les dans la bouche.

L’est dans la bouche.

L’est dam le à bouche.

Les dents-là bouche.

The bottom two transformations in this imaginative list are less than transparent. The first must be read as “II est un dam [mal] ici à la bouche:” in other words “I have a toothache”; the second as “Bouche [cache] ces dents-là” or “shut your mouth.” And as if all that weren’t enough, Brisset then inverts the two terms of his paradigm and leads us through the teeming possibilities of “la bouche, les dents:” “la bouche 1’aidant.” etc.13

Reading more than a few pages of this kind of thing can be wearisome, but the associative processes that are compulsively at work here affect us all to a greater or lesser extent when we resort to language, whether we are for puns or against them. As Lecercle points out, in taking words as the foundation of knowledge about the world, Brisset has only followed the age-old tradition of “speculative etymology” practiced by such serious thinkers as Heidegger. “There is nothing strange or unusual in the idea that words have a history, and that this in turn reflects the history of a people who speak them. …Why should not our words contain our roots?”14 English abounds in similar cases. For example, a popular name for British pubs, “The Elephant and Castle” is a phonological reproduction of the French phrase, “l’enfant en castile,” the nickname of Bonny Prince Charlie when the lad was hidden in a French tower. We Brissetize language because it Brissetizes; delire only reveals a mechanism always in play. All ideas with similar sounds have the same origin and all refer, initially, to the same object. This idea is also the key to the Lowie/Lowrey team. The formal link between Duchamp and the MJT is the word “jurassic,” originally an adjective referring to the Jura region along the French-Swiss border, later adopted as the name of a geological era whose remains were first classified there. In 1912, accompanied by Picabia and Apollinaire, Duchamp took a trip to this region, which journey Lowie/Lowrey believe sparked a/the revolution in his conception of art. “The Museum of Jurassic Technology’s name, we assert, is specifically derived from Duchamp’s “Jura-Paris Road” notes.”15 From this perspective, “conceptual” art is Jurassic art; hence the Museum of Jurassic Technology must precede Duchamp’s discoveries, for where else could he have found them?

From this perfect beginning, Lowie/Lowrey proceed to Brissetize with the language of modern art history. For example, the “divine blossoming” of the “five hearts” of the “mother machine” in Duchamp’s Jura- Paris notes, is clearly shown as a reworking of the Tree of Knowledge and Life, by the five coffin-shaped display cabinets in the MJT’s exhibition, Garden of Eden on Wheels: Selected Collections from Los Angeles Area Home and Trailer Parks. “Amazingly enough,” as the pair enthuse in their book, “the apple has five seed chambers called “carpels,” sometimes refered to as five ovaries.”16 They go on:

“The image of a porcelain figure of a young woman, featured in the signage and catalogue for the Museum’s exhibition, …is important to reading Duchamp’s Readymades, Fountain and Peigne (Comb).”17

The denouement is given in a long quote extracted from an article on modern plumbing, abbreviated below.

“Porcelain. The name of the ceramic used for toilets is the same name used to describe a teacup, a baby doll, …the exquisite corpse that is femininity in patriarchal culture. …By the nineteenth century, ‘woman,’ then long associated with open waters and foods, came to be associated with the control of floods, the control that was modern plumbing.”18

Delire, as Lecercle says, is a perversion that “consists in interfering, or rather taking risks, with language,” a perversion not defined in opposition to the norm, but one that shows the norm as it really is, albeit we require extreme examples to recognize this fact. If one may see the story of modern art as a “language,” then, I would argue, the work of Nicholas Lowie and Sheridan Lowrey is an exemplary case of delire.

Christine Wertheim is a faculty member of the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts where she teaches writing, literature, feminism and critical theory. She co-organizes, with Matias Viegener, an annual, two-day conference at REDCAT on contemporary writing — Sance in 2004, and noulipo in 2005.