In Ecstasy: In and About Altered States, exhibition organizer Paul Schimmel argues that the sundry works that comprise his show are part of “an iconographic thread” that leads back to “antique depictions of the bacchanalia [and] baroque representations of religious transport.” Since it is no longer convention in the 21st century to worship Dionysus, and as recorded instances of religious rapture are decidedly thin on the ground and frequently confined to the pages of the National Enquirer, Schimmel runs the risk of understatement when in his introductory essay he notes that “such concepts as the authentic, the transcendent and the utopian have been subjected to sustained critique” in recent years.1

The euphoric state captured by Gianlorenzo Bernini in The Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1645-52), for example, remains persuasive only as a grand relic of an age in which religious mysticism was part of the collective consciousness. The critical community would doubtless consider contemporary sculpture created in this manner little more than neo-Romantic camp, illegible as a sincere gesture, and likely a parody of Baroque magnificence. This suspicious critical turn is paralleled in culture at large where faith is foremost a contested aspect of social identity and political policy, not a spiritual attitude that encourages in its adherents the experience of altered consciousness. If inner rapture has a place in today’s culture, that experience must be equipped to negotiate pervasive resistance to such “utopian” concepts in our comparatively sober and stoic social climate. With these constraints in mind, it comes as no surprise that in common parlance the terms “ecstasy” and “altered state” are now linked to a far less elusive and mystical secular practice: the use of illicit drugs to chemically alter our behavior and perception. It is the relationship between the perceptual possibilities of drug use on one hand, and the production and experience of visual art on the other, that Schimmel and co-organizer Gloria Sutton explore at the Geffen.

Though the exhibition’s introductory wall panel euphemistically claims that included works capture or attempt to simulate “metaphysical states in representational form,” a cursory stroll through the carnivalesque installation reveals the exhibition as more playground for the psychoactive mind than interrogation of perception or metaphysics. Though this discrepancy is doubtless the result of institutional policy (one can only imagine the public furor if the words LSD, heroin, or MDMA had appeared in the wall didactics), the now-familiar manga aesthetic of Takashi Murakami’s DOB in the Strange Forest (1999), while stunningly crafted and graphically captivating, is by no stretch of the imagination an urbane examination of metaphysics as the adjacent text would claim. In this light, Schimmel’s argument appears somewhat disingenuous. As a result, the show often feels like a sprawling in-joke—broadly accessible, yes, but sufficiently veiled to pass under the radar, all the while encouraging the snickering of those “in the know.” Even the exhibition’s title—Ecstasy—is multivalent enough in meaning and association to avoid being connected exclusively with the drug of the same name. The title, like the real concept of the show, remains hidden in plain sight.

That is, of course, until one turns to the far less public domain of the catalog, which reproduces amongst other texts an essay titled “Confessions of a Middle-Aged Ecstasy Eater” (2001): a fast-paced and admittedly riveting account of one person’s experience with the psychedelic drug that lays bare the conceptual interests. However, what is plainly stated in the catalog is subjected to waffling and obfuscation in the exhibition itself. As one enters the show, one is not, for example, promised homage to barbiturates or hallucinogens and their inspirational effects, much less an interrogation of the imagery associated with club culture, but instead an examination of “the basic mechanisms of perception.” Furthermore, we are asked to accept the assertion that the experience of art “is itself an altered state,” while the more radical and indeed genuine terrain of the exhibition—the effect of psychoactive substances on the conception, execution and perception of visual art—remains implicit. Ultimately, these inconsistencies read as conceptual hedging.

While the essential premise—that transcendent states as evoked in recent art can often be better understood through the lens of “drug culture”2—is plausible, the realization of this concept independent of the catalog appears at times inconsistent and muddled in the exhibition. Schimmel’s lucidly written essay provides analysis of the historical associations between a dizzying array of mind-altering substances and the creative act, in particular the perceptual effects of LSD and Ecstasy. None of this technical or historicizing information, however, is brought directly to bear on the individual objects or on the argument constructed by the union of these works in the context of the show. Additionally, it is not always clear whether the inclusion of a given work under the thematic banner benefits the work in question. In fact, the compulsion to understand the relationship of the object to the concept is a recurrent hindrance that actually occludes—or at least limits—the visual potency of the object.

The first and perhaps most conceptually dynamic object on display is also the most radically dissimilar from the other works. While the majority of pieces in Ecstasy are cleverly punning, intensely color-infused, environmentally immersive, or engaged in some manner of perceptual trickery, Public Fountain LSD Hall (2003) is by contrast critically canny. Klaus Weber had his crystal fountain fabricated by Osler, the company that manufactured a similar fountain for the Crystal Palace during London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. The substance flowing from the fountain at the Geffen is, according to a nearby certificate, potenized LSD prepared by a licensed homeopath. Surrounded by a protective though far from impregnable wall of Plexiglas, it is quite conceivable, as the exhibition catalog notes (again rather cagily), “[I]n theory, visitors could drink from Weber’s fountain to heighten their senses.”3 With this work, Weber asks viewers whether they are prepared to accept as truth all that is seen, heard, and read in the authoritative context of the museum.

Claims to truth and authenticity made by this work give rise to a multitude of provocative questions: Is there really LSD in the fountain, and if so why is there no guard nearby to fend off any potential drinkers? Since LSD is indeed illegal, has the museum received special dispensation to use it as part of an installation? Or are the cursory barrier and certificate provided by the Pacific Academy of Homeopathy (a genuine organization: http://www.homeopathy-academy. org/main/) part of a hoax intended to test the limits of believability and cultural acceptability? Does the presence of minimal security invite the bold patron to sample the water? And does it matter whether there is in fact LSD in the water, or is the audacity of the gesture enough to transcend normal limitations? In his critical engagement with social mores, institutional authority, and the creation of meaning through signage and siting in a museum context, Weber’s work stands alone.

Being determinedly conceptual and comparatively non-visual, Weber’s installation is also one of a few exceptions in an otherwise visually boisterous exhibition. Pierre Huyghe’s L’expédition scintillante, Acte 2 (light box) (2002) typifies many of the other works on view. Resting on the floor at the center of a dark gallery is a roughly 6’ x 6’ white box with an identical box suspended above it. A wispy layer of fog hangs languidly between the two boxes as moving light fixtures project different colors through the haze from above and below. This elegant installation draws attention to the most telling disparity in the exhibition’s stated premise. We are told in the introductory wall text (the only included in the show) that the objects in the exhibition fall into “two distinct but overlapping” categories: those that “capture metaphysical states in representational form,” and those that “simulate or induce these experiences in the viewer.” It seems self-evident a third category is equally apposite and perhaps more broadly applicable: objects that would provide endless and engrossing visual stimuli for those industrious patrons who enter Ecstasy armed with their own supply of mind altering goodies. Judging from the number of slumbering figures that littered the floor of L’expédition scintillante, or who giggled their way through Carsten Höller’s Upside-Down Mushroom Room (2000), this was a popular course of action.

During the ‘60s, Minimalists famously sought to eliminate the conventional spatial and ideological division between viewer and object by crafting works that occupied the same space as the spectator. Taken as a whole, Ecstasy proposes and in many cases successfully realizes a phenomenological field between object and viewer that is far less stilted and significantly more proximal than the majority of museum exhibitions. This is particularly evident in Höller’s installation, where viewers are invited to sit in a room drenched in unforgiving fluorescent light and contemplate the slow rotation of red and white inverted toadstools suspended from the ceiling; in Ann Veronica Janssens’s Donut (2003) in which the viewer is assaulted with a succession of vividly colored, concentric circles that flash up on a large screen and trigger cool retinal afterimages; and in Ann Lislegaard’s I-You- Later-There (2000), in which an expansive, white, stage-like plane leans improbably against the gallery wall bathed with lights that flash in rough synchronization with a soothing female voice that relates in impartial tones the quotidian actions, decisions and thoughts of her daily life. The effect of the latter, like many objects in the exhibition, is at once accessible, aesthetically compelling, and hypnotic, thereby inviting a close, prolonged and genuinely engaging experience.

While Janssens’s and Höller’s work, like that of Tom Friedman, Roxy Paine and Murakami, has observable relationship to club culture and/or to the perceptual effects of drug use, in at least three of the most sophisticated and impressive works—namely Olafur Eliasson’s breathtaking Beauty (1993), Erwin Redl’s LED installation, MATRIX II (200/05), and Paul Noble’s masterful, large-scale works on paper—it is useful to consider how (if at all) these works relate to or benefit from inclusion in Ecstasy. Though Schimmel is savvy enough to sidestep the much maligned issue of intention, it might be productive to resurrect, if only temporarily, this very issue, in order to ask how the aims and means of the aforementioned artists relate to Schimmel’s conceptual paradigm.

Eliasson’s Beauty displays all the traits of aesthetic refinement, economy of means, and command of media that characterize his best work. Generally, the artist goes to great lengths to reveal his installations as theater and, consequently, the viewer is often confronted with a “backstage” view of the mechanics used to realize a sublimely beautiful moment. Beauty, as the name might suggest, downplays such deconstructive gestures in the interest of maintaining the dazzling effects of the installation. Eliasson uses strobe lights to arrest the downward motion of water droplets that fall in a thin wall of glistening particles onto a sharp black slab on the floor. The sprinkler system is completely unobtrusive in this installation and as such, the “beauty” of the spectacle seems impenetrable. What is the relationship between this work and the theme of the exhibition? Use of a strobe light may allude in some way to the club scene, but the cultural associations of this device seems peripheral in the context of an installation that clearly exploits the attributes of light and water to achieve a formal effect. If anything, attendant cultural associations are buried by the insistent fine art quality and high craft of Eliasson’s work.

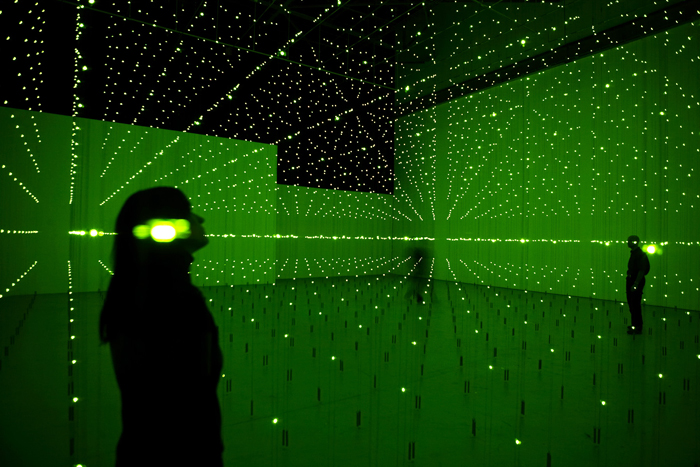

To belabor the parallels between Redl’s MATRIX II and drug or club culture seems similarly forced and unproductive. Thousands of individual green LEDs were fused to copper wire and arranged by Redl in a rigid grid to create cascading passages of receding space and shifting horizon lines that appear before the viewer as shimmering experiments in Albertian perspective. As Sutton notes in the catalog, MATRIX II is “an effort to understand how abstraction can be transformed into a physical sensation.”4 Redl seems far more interested in the historical valences of abstraction and the creation of perspectival sensations in three dimensions than in the capacity of his work to induce or simulate an “altered state.” Granted, this elegant restructuring of space does radically alter one’s sense of figure/ ground relations, but it is achieved through empathically formal means and, resultantly, one is never in doubt that the artist’s sleight of hand is responsible for our altered perspective. The effect might be sublime, even ecstatic, but the means are technical and comprehensible.

By contrast, British artist Paul Noble uses conventional pencil and paper to craft sweeping alchemical dreamscapes, which are informed in equal parts by Boschian allegory and the repeated patterns of computer graphics. Noble’s dystopic, surreal visions are pristinely executed and endlessly rich in detail, but again, why a work like Ye Olde Ruin (2003-4) is included is far from clear. Noble’s hybrid creatures, fictive landscapes, and layers of graphic detail make his work ripe for examination and analysis, but unfortunately, the desire to understand its place in Ecstasy predominates. The division between Noble’s drawings and the rest of the show is exacerbated by their isolated placement in the cavernous rear gallery of the Geffen. This installation choice coupled with the character of the works themselves might lead one to wonder if they are part of the exhibition at all.

A serious word must be reserved for an untitled piece by Tom Friedman. While other works by Friedman included in Ecstasy take the accoutrements of drug culture—pills for example—as the starting point for elegant sculptures that draw parodistically on the vocabulary of Minimalism, this work stands apart from the others, and indeed from the rest of show.

Untitled (2005) is not mentioned in the catalog and is given scant, almost dismissive treatment in the exhibition brochure, a rather startling fact given the gravity of the subject depicted. Tucked stealthily in a corner, one could easily ignore this work, which is probably why, when discovered, it comes as such a shock. Sculpted from what appears to be light blue insulating foam, Untitled depicts a single tower. Attached by its nose to the tower is a small aircraft made of the same blue material. There is no mistaking the subject matter; it is deeply striking that the now-familiar perpendicular angle formed by a horizontal passenger aircraft and a vertical tower has assumed such emotional resonance. With no analysis other than one terse line in the free brochure (which informs us that in “Untitled (2005), which is being shown simultaneously in New York, Friedman uses rigid insulation to suspend singular a moment”), this monumentally important subject runs the risk of being lost in a cavalcade of punning, whimsical installations.

Clearly, the critical art community has not encouraged artists to respond to the imagery of 9/11 in direct or mimetic terms. Indeed, photojournalistic images are apparently the only admissible form of visual reflection on those horrific scenes. As Sarah Boxer perceptively noted in early 2002, “The events of September 11, 2001 were beyond measure. But when the day ended, the visual limits were fixed.”5 Considering this statement, to engage this subject at all is in my opinion to be applauded. But while it was bold and even courageous for Friedman to make such a piece and for Schimmel to include it in his show, its connection to the broader theme is unfortunately left disturbingly ambiguous. Although Friedman’s sculpture deserves to be seen and discussed, its inclusion in Ecstasy seems impulsive and ill-conceived. Such treatment does not befit the subject, the efforts of the artist, or the exhibition itself.

Both the spectacle and experience of club culture is defined by the writhing masses that form the vital essence of such events. Club culture gives rise to a social aesthetic. As is exemplified beautifully in the catalog by a reproduction of Andreas Gursky’s photograph May Day III (1998), these scenes materialize in representation as places of shared space, energy, and time. Be that as it may, the most persuasive works in Ecstasy are determinedly anti-social and do not benefit from the writhing masses that swarmed through the galleries on both occasions I visited the show. At its best, the experience of a club can generate a kind of group hypnosis in which sounds, images and physical sensations are indivisible. Many of the works included in Ecstasy by contrast encourage a quiet, meditative experience best enjoyed alone. This holds true in the case of works by Eliasson, Sylvie Fleury, Höller, Huyghe, Janssens, Redl, and others.

Schimmel and Sutton are able to propose, and in some cases demonstrate, a connection between ecstatic, altered states as visualized in contemporary art, and the perceptual effects of stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens as experienced in culture at large. However, this point is sometimes made at the expense of the integrity of the works in question. One is often left with the sensation that pieces with largely formal and perceptual concerns are conceptually shoehorned into a framework that delimits their meaning. While a visitor may be persuaded by Schimmel’s observation that “ecstasy” is now largely disassociated from religious or spiritual life, the same visitor might justifiably be suspicious of the implication that all of the works in Ecstasy are best understood through the lens of drug culture.

Christopher Bedford is a Curatorial Assistant in the Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the J. Paul Getty Museum and a PhD Student in Art History at the University of Southern California.