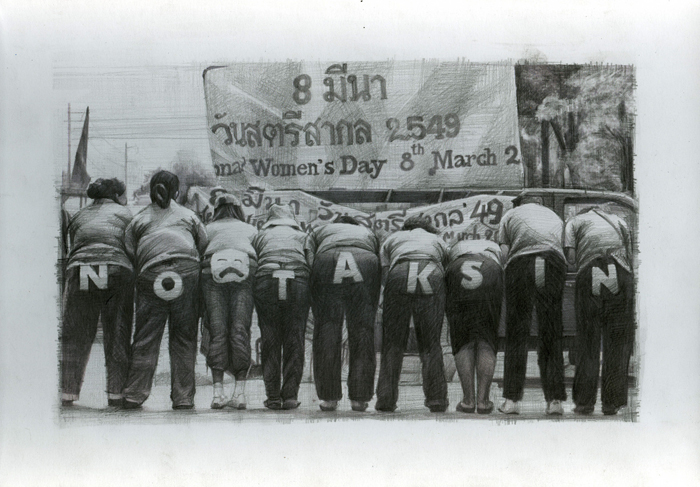

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled (demonstration no. 174), 2006. Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE.

Rirkrit Tiravanija is our latest incarnation of the post-Warholian bad boy. Avoiding the crumbling pasteboard facades of Hollywood glamour, Rirkrit takes the colors of his factory palette not from the pages of celebrity tabloids, but from the headlines of the International Herald Tribune, which form the crux of his most recent solo show in Los Angeles. Our bad boy is “bad” because he plays the Duchampian game of decisively deriding the edges of art itself. He maneuvers his role of artist-as- conceptual-impresario in attempt to rub out the separation between art and public, promoting his own brand of egalitarian social interactivity and utility.

Though Tiravanija’s practice spans the spectrum of media and installation, he’s best known for his conceptual cookouts where he sets up shop at your local gallery, museum, or art fair and makes vegetable curry by recipes cadged from his grandmother’s cookbook (leftovers of which are for sale to collectors). His work has also included famously bricking the entrance to a booth at Art Basel in 2005 (“Ne Jamais Travaillez” spray painted on the wall in mock defiance) as well as a rather lackluster collaboration with another relational aesthetics stand-by and ubiquitous art world event invitee, SUPERFLEX (in a collaboration dubbed “Social Pudding” that made up his last show at 1301PE). Such seemingly altruistic offerings of free consumables make him a regular face on the international scene and his institutional critique-made-fun enables him to constantly take his side-show on the road to a seemingly endless series of big deal international art events. Tiravanija’s forays into commercial galleries provide the saleable objects to hang his all-pervasive persona upon. His conceptual cookouts and anodyne institutional critique-play have made him and his work readily likeable, helping him to win a string of prizes (most famously the Hugo Boss Prize in 2004), while a growing roar of critical acclaim has secured his position as a powerful figure in contemporary art.

For his solo show at 1301PE, titled Demonstration Drawings, Tiravanija commissioned other artists—mostly former students—to create graphite drawings from photos of demonstrations from around the world taken off the pages of the International Herald Tribune. The drawings are arranged on two intersecting walls in no interpretable design (even the gallery checklist has them out of order).

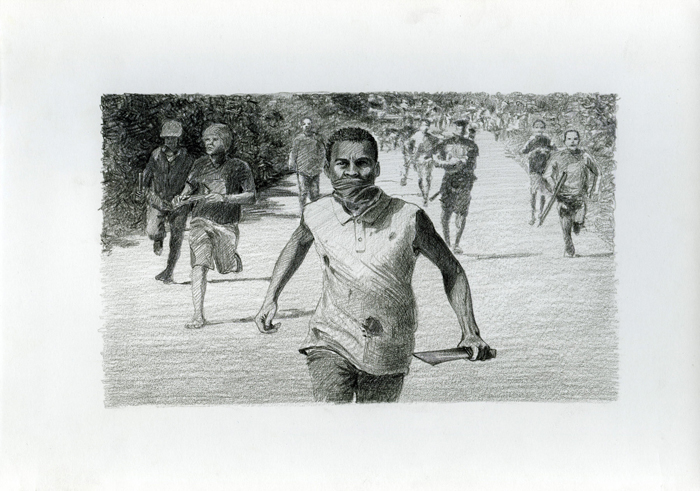

The images in these drawings depict real demonstrations that occurred very recently, capturing the Stürm und Drang bubbling at the edges of a fraying world order that defies the commands of its first-world architects. To view the hundred drawings clustered close together is disconcerting—a world of problems carefully redrawn and seen all at once. Looking at each small piece in turn, I kept having minor moments of post-modern dread as described in the pages of DeLillo. A masked man armed with a machete runs with a crowd behind him; without the pointed description the Tribune would give, we are left in the dark whether he’s being chased by or leading the mob. A large group of masked protesters in jeans and sneakers navigate a trash-strewn terrain, throwing bricks at an unseen enemy, probably police, beyond the edges of the frame. Though many of the drawings have recognizable signs and placards that point toward moments of distinct rupture, others don’t. And the ones that don’t are the most disconcerting. Without being anchored by any markers of time and place, they are the nameless, faceless scourge of opposition and riot, the spike of poison that threatens to bring the system as-we-know-it crashing down—the international situation desperate as usual.

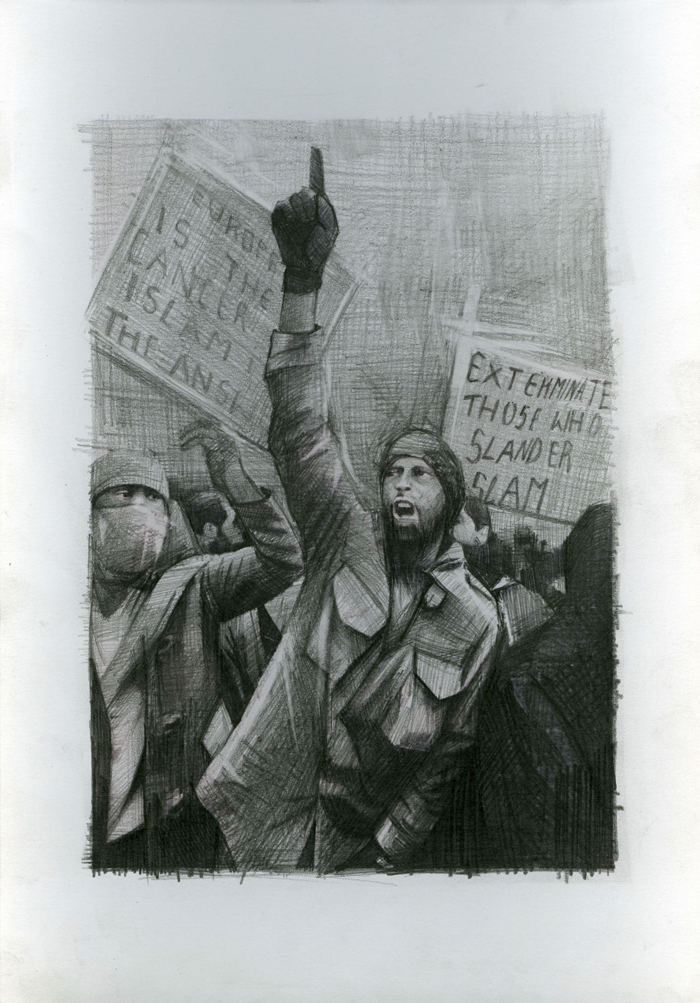

Many of the images are of protests in Thailand where the work was created. The most humorous of these demonstration drawings displays the derrieres of a particularly inventive group of Thai protesters, each one’s ass marked with a letter of the phrase “NO TAKSIN” punctuated in the center with an un-happy face. The discontent shown in these protests has finally manifested in a very real bloodless military takeover and overthrow of the democratically elected government of Thai premier Taksin Shinawatra. The coup invests these pieces with contemporary resonance, especially given that Tiravanija is a Thai national currently sticking it out in Bangkok. But placing the recognizable protests side- by-side with the images of unidentifiable protesters shows Tiravanija’s ability as an artist and the son of a diplomat to slip in and out of the world’s tensest places, if not physically than at least conceptually, negotiating between both those represented by the drawings and those outside of them, or in other words—us and them. The protests in the drawings force viewers to re-examine their relationship (within the comfort and stability of a first-class art gallery in L.A.) to the dramas of the world being played out in the drawings and, moreover, Tiravanija’s relation to it. And the world leaves no shortage of events to shock and awe; one particularly potent work shows a young Arab man, black-gloved hand pointed into the air, while behind him placards read “EUROPE IS THE CANCER, ISLAM IS THE ANSWER” and “EXTERMINATE THOSE WHO SLANDER ISLAM.”

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled (demonstration no. 186), 2006. Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE.

The energy and anger of Tiravanija’s subjects are evident, but they are contained by the white space of the page that surrounds the drawing, the bars of the frames, and ultimately, the pieces are tamed under the banner of Rirkrit Tiravanija. I’m reminded of Sam Durant’s pencil drawings of ‘60s protests, accompanied by light boxes with the words from the protest placards written on them. Like Durant’s drawings, Tiravanija’s seem to be a kind of political art that in actuality challenges nothing, and puts nothing at risk. In his defense, at least Tiravanija is dealing with contemporary events, but they are so carefully re-presented that the drawings ultimately draw the teeth out of the moments that they describe. Stripped of moral judgment or political edification and haphazardly installed, each rendering carries the same weight as the next, so rather than more deeply engaging us in a world in turmoil, they reduce these events to the level of merchandise. By re-drawing them, however, Tiravanija takes the subject one step farther removed from the real, packaging world events under the Tiravanija brand for easy consumption on the gallery wall.

Despite the many qualms I have with the work and the methods of its artist, the drawings manage to bring a certain attention to political events in a personal way that can be meaningful. A number of the drawings are funny, some are scary, a few of them are even heartbreaking, and to see them all clustered together brings about a kind of cathartic awareness of international events and our relation to them. The work sometimes succeeds despite itself by capturing a moment in time, directly reflecting the turmoil of a world in transition that is tense and dangerous.

Tiravanija’s aesthetic practice typically involves setting up laboratories or situations for people to gather together and act out ideas, which in this case attempts to mirror the acts of the demonstrations themselves. But I’m unable to get past the tincture of commercial ego and Tiravanija’s distant relationship to its creation. Tiravanija neither drew the drawings nor oversaw their installation (he was in Bangkok at the time of the opening, during the recent Thai coup d’etat), though of course his name headlines the press release. The off-site social interaction set up in Demonstration Drawings appears to be the production of merchandise for a solo show by Rirkrit Tiravanija.

Though the gallery states that the show has more to do with “an idea of the world than a fascination with the hand,” to subtract one from the other is fallacy. Style and content are as closely wedded as art and commerce. Redrawing a subject with such painstaking attention to detail and verisimilitude forces the drawer to re-experience the event, but also sentimentalizes it through his or her loving care. We look for the individual identity of the artists in their execution— their shade, line, and style. But under Tiravanija’s direction the drawers’ task is to simply copy, and in the end, each one of the commissioned artists remains a nameless automaton. Recreating photos through drawing both humanizes the photos and dehumanizes the nameless former students who created them.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled (demonstration no. 172), 2006. Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE.

In addition to Tiravanija’s emphasis on social interaction, another plank of his platform is use-value. Take, for example, his quip in an in interview in the Brooklyn Rail (February 2004): “What I am doing is to takes (sic) Duchamp’s urinal, put it back on the wall and piss into it.” Thus marking his territory, he takes art (the Duchamp urinal), peels away the institutional penumbra (putting it back on the wall—the museum wall or the bathroom wall was not specified), and in one bold move both takes away its powers as an icon and puts his own signature on it (figuratively speaking), making it art again. By using it, he subsumes an iconic piece of twentieth century art and makes it Tiravanija’s. His aggregate performances, from cookouts to expectoration, form the bulk of his work and appear to easily fall under the rubric (consciously or unconsciously) of relational aesthetics. Last season’s French Pomo trend of choice, relational aesthetics is defined by its coiner Nicolas Bourriaud in the glossary to his book of the same name as an “aesthetic theory consisting in judging artwork on the basis of inter-human relations which they represent, produce or prompt.” This largely European phenomena, formulated during the heady days of the Information Superhighway and user empowerment, attempts to decode the viewer’s relationship to art by creating an art experience. Create a space, connect people, and feed them a few terms (or curries). Tiravanija is a poster boy for relational aesthetics, but has managed so far to keep his hands largely clean from the grotty side of art making: commerce, especially that of the simple sale of merchandise. In fact, his actions purport to undermine the petty careerism and product-making that defines the work of many of his colleagues. Demonstration Drawings underscores many of the failings of this kind of practice, which strips art of its last vestiges of exception and merely makes it a wing of a service economy, absorbing nameless skilled workers into a final product for the brand name.

Though Tiranvanija has absorbed and repackaged others’ work (and the ire of international protesters) into a posh L.A. gallery with price tags, we’re not buying the work per se but a piece of the myth of the artist behind it all. Like Warhol, Tiravanija makes everything in the world—your sense of community, your political unrest, your entrails—a stage for Tiravanija. Unlike Warhol, this masterful sleight of hand is inflected by his foundational programmatic agenda of soft-focus social interactivity, devolving quickly from service to product with an all encompassing agenda. Though often coached in disingenuous terms, the system is simple: Everything is Tiravanija’s, but it’s also yours.

Andrew Berardini is a writer living in Los Angeles. His most recent projects are a revised translation of Jean Baudrillard’s In the Shadow of the Silent Majority to be published in Spring 2007 and a recently completed novel.