It’s after the end of the World. Don’t you know that yet?

—Sun Ra and His Intergalactic Research Arkestra

The world did not cease to exist as the year 1999 came to its end. This non- moment is one of the defining events of the demographic labeled Generation X. It doesn’t matter that few were actually concerned that a massive mainframe malfunction would bring the industrialized world to a halt. What matters is that there was an expectation—even acceptance— that it might. It didn’t, and now we have to live with it. The Baby-Boomers got to be America’s teenagers, acting wild and experimenting. Generation X has to become America’s young adults, slowly assuming dreaded responsibility and beginning to have History. A Big Bang was needed to signal the transition into adulthood, yet nothing happened. Rather, we have been left frozen in a period of adolescence even as that act is running out of options. The world has gone on to show that far worse things happen than the end of the world (terrorism, hurricanes, poor civil engineering, tsunamis, crooked politicians) and yet, there seems to be a blank effect from these events; there is a sense of limitation in our ability to react.

Jeremy Blake’s video Sodium Fox, intentionally or not, captures this blank malaise of a generation. Sodium Fox is a collaboration between Blake and David Berman, the front man for the band Silver Jews.1 Berman wrote and read poetic fragments that Blake cut up and assembled into a disjointed, stream of consciousness script that more or less follows the unnamed narrator through a brief dark night of the soul that spans his whole life. The video imagery itself is just as chopped up as the text, but some recurring motifs hint at a linearity of narration and give a sense of weight to the slippery language.

Ostensibly, the story is that of a man looking for validation, if not love, in an empty, somewhat cruel world. It is a re-telling of the standard hero’s quest. The unnamed character’s narration begins with a brief, world–weary introduction (“I’m definitely the kind of man who knows when its over/How amazing that it can begin right here/Without the drama of the last chance”), and moves on to a biography delivered in concrete details about his mother and more elliptically described childhood exploits before it charges into the main body of the story. The narrator is in quest of “a lifelong conversation with one person,” and the answer to “Could I be saved by something as simple as caring or not caring?” which is, as Blake puts it in his artist statement, “the central Gen X question.”

The images that pile up underneath the narration sometimes work as visual puns against the text, and at other times reinforce it. So much coded imagery piles up in Sodium Fox that it is daunting to try to interpret it. However, what is important is neither the codes nor their interpretations but that these references point to specific times and places, mostly the late 1970s and early ‘80s. They act as the bedrock for the loose narrative, and set the tone for the narrator’s psyche. Commercial imagery—the stuff that is supposed to produce the consumer— becomes, in Blake’s video, and for so many of his generation, a tool for his own expression. Interiority and exteriority become confused and interchangeable. Too many familiar images stream by to name—though the re-appearance of George Burns as God from the Oh, God! films of the late 1970s and ‘80s is particularly iconic to those who spent too many wasted hours in front of television during the early days of cable.

Jeremy Blake, Sodium Fox, 2005. Still images from DVD. Courtesy the artist and Honor Fraser.

As a whole, Sodium Fox is very, very flat. Physically, it is presented on a large flat- screen monitor. Berman’s narration is delivered without affect, in a wry near monotone that rises and fades and is altogether hard to latch onto. The imagery itself is delivered in layers upon layers that slide frictionlessly over and beneath one another, fading in and out without interacting; in one sequence “TIE-fighter” spaceships from Star Wars shoot cartoon lasers at beachfront homes without effect. The layers don’t add up to an illusory depth. Rather, they reinforce the glassy surface of the monitor, the window, and the mirror. They present impenetrable, unreal spaces. The flat-screen monitor redoubles this effect; the video becomes an object instead of a space. These are not negatives. The flatness in Blake’s work comes across as an extension of the stereotypical Gen X blankness—the uncaring pose, a kind of coolness.

Blake’s videos are often described as psychedelic, and his work does share many traits associated with art that captures an hallucinogenic experience: disjointed narrative, overload of imagery, and over-saturated colors. Typical psychedelia, however, seeks to envelope the viewer in sensory chaos or abandon. Here the emphasis on flatness presents a strange new world that the viewer is separate from and will never join.2 In Blake’s work, the viewer is watching a recollection.

All of this makes Blake’s an intriguing if somewhat flat and removed study of what one type of American is experiencing in his internal landscape. It doesn’t tell us why this is important or why we should pay attention to it. To get a sense of this, it is interesting to view Sodium Fox through the lens of Greil Marcus’s new book The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice. The thesis of The Shape of Things to Come is that prophecy is not the art of predicting the future but of determining how the past will look from the future. In essence, prophecy determines how a time will be judged by its progeny. The distinctly American version of this, according to Marcus, is that all of our great promises are already always broken. The great American work is to correct these broken promises. America is continually trying to live up to its past and, Marcus argues, the act of being American is to bear the weight of these broken promises. This is not a bad thing. To Marcus, America is forever a work in progress.

Marcus combines this idea with his impressive ability to read every action as shaped by powerful forces and at the same time shaping the currents that create these forces. Through Marcus’s eyes, every act of art is important, from the most intimate songs played alone in a room to the Gettysburg Address. Marcus’s book argues that everything is connected, influenced and influential; every act, and non-act, has reverberations. Sodium Fox is a small, private story, but one that is shaped by millennial forces—the fear of the end of the world that was to happen in 2000 but didn’t. The central point of view in Sodium Fox is that of a Generation X “everyman” (if you can take everyman to mean straight, white and middle-class). Gen X is a strange concept, but it is a fine blank definition for a generation raised on unfulfilled anticipations. X is the empty signifier. Through the lens of Marcus’ book, the character in Sodium Fox actually takes on the role of hero as he seeks answers to the questions consuming a generation: “Could I be saved by something as simple as caring or not caring?” The current American experience seems to sprawl out before us like the hallucinatory movements in Blake’s video. The decision to care or not suddenly looms large.3

At the end of Sodium Fox there is a feint towards closure as the narrator finds solace in the bosom of Sodium Fox, a beautiful virgin prostitute commanded by George Burns-as-God to love the narrator. But this conclusion is whisked away in the final scene showing Sodium Fox sunbathing on a beach in winter, nearly naked except for a bikini, sunglasses and heavy furry boots. Planted on the otherwise empty beach is a flag emblazoned with a cartoonish skull, and the narrator speaks the last words of the video: “It’s going to take four or five years to describe.” Then the video seamlessly loops back to the beginning with the words “I’m definitely the kind of man who knows when its over.”

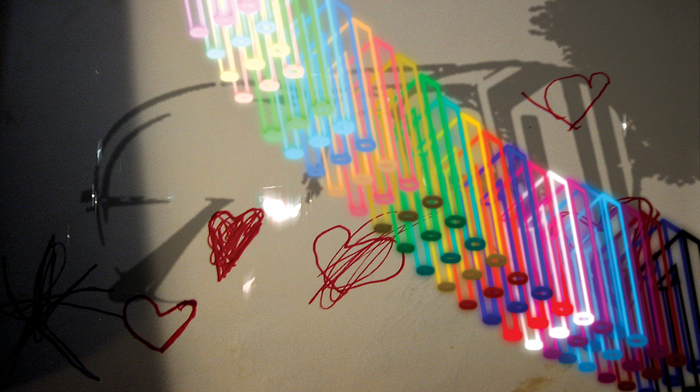

And that is seemingly the end. Blake’s narrator is locked into this loop of perpetual searching, just as Marcus’ America is continually looking back and judging itself, forever trying to fulfill its promises to itself. Blake, too, is dealing with unfulfilled promises of Modernist pasts. As the narrator enters the museum/massage parlor where he meets Sodium Fox, an image of a gallery with a Rothko painting is briefly visible before it is swept over by doodled hearts and Blake’s luminescent color fields. Later, towards the end of the video while the narrator’s voiceover speaks “I stood in a puddle of my own tears, like the skeleton who drinks a glass of water in the classic sight gag,” a skeleton appears, pouring the contents of a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon (the beer of our fathers) through the top of its head. In the background, in a run-down office with aparticularly ugly dropped ceiling, is what appears to be a piece by Dan Flavin, multi-colored tubes glowing brightly.4

Jeremy Blake, Sodium Fox, 2005, Still image from DVD. Courtesy the artist and Honor Fraser.

In Sodium Fox, Blake is reaching through the past, grabbing on to the well-worn clichés of the hero’s journey, Modernist utopias, and the belief that love saves all. It could all seem to be a bit much. However, as Marcus predicts (every American promise carries with it the origins of its own betrayal), Blake inserts at least two more clues that everything may not be what it seems. One is the recurring appearance of the book The Dictionary of Misinformation, originally published in 1975 by Tom Burnam. The Dictionary was the book to set the record straight about all kinds of misinformation, from the fact that a black-eyed pea is actually a bean to the fact that prohibition didn’t outlaw the consumption of alcohol, only its manufacture, sale or transportation. It was the hip tome to carry around to show you were in the know. The other recurring clue Blake keeps showing us is the “impossible trident” optical illusion, in which the shape has three prongs on one end but has only two at its origin. This shape is also known as the “blivet,” which means, in WWII slang, anything completely unmanageable and fucked up, like trying to pack ten pounds of shit in a five-pound bag. The figure appears in Sodium Fox on a magazine cover and as a blinking neon sign on the museum/massage parlor. Also known as a “poiuyt,” the shape notably appeared on the March 1965 cover of Mad Magazine by Norman Mingo, featuring Alfred E. Neuman, literally four-eyed, balancing the blivet on its impossible middle tine. In Sodium Fox, Blake has altered this cover himself, changing the magazine title to “Artform” and adding Neuman’s catch phrase “What, me worry?” Again, Blake has packed in so much information that it simply can’t be repacked.

The presence of the poiuyt and the Dictionary wink at the fact that things aren’t to be trusted and aren’t what they seem. Narrators are untrustworthy, presidents mislead and images lie. This is the central strategy of Generation X, to want to care and to undercut caring itself by loading up with the tools that allow ourselves to not care. Blake’s video seems to be calling for a commitment to one path or the other.5 Failure to do so is to be forever locked in a pattern of vacillation. Though perhaps not.

Karl Erickson is an artist and devoted student of over-saturation. Recent exhibitions include Streetsigns and Solar Ovens at the Craft and Folk Art Museum, Louis Morris at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, Interstellar Low Ways at the Hyde Park Art Center, and Fair Exchange at the L.A. County Fair.