In his compilation of essays Landscape and Power, W.J.T. Mitchell argues that landscape representation has always been “an instrument of cultural power.”1 He identifies various historical approaches, such as Dutch landscape painting, English landscape drawing, and nineteenth-century American photography of the West, as ideological instruments based on a complex network of cultural, political, economic, and class codes.Beginning with the development of single fixed-point perspective during the Renaissance, all landscape information was traditionally arranged to conform to a scientific, dualistic, and controlling view. The frame around a scene reinforced a sense of human control over chaotic nature while simultaneously imparting the appearance of the “natural.” In this way, Mitchell explains, the imperialistic landscape managed the spectator’s perceptions in order to silence any dissonant political discourse concerning colonialist agendas, tenants’ and laborers’ rights, and the plundering of resources.2 Today, as globalization exerts its forces, many contemporary artists are working to resist or destabilize the “truth” of such landscape conventions. (Photographers Edward Burtynsky, Richard Misrach, and Robert Adams and painters Ed Ruscha and Valerie Hegarty come to mind.) They suggest that a “pure” transcription of landscape is a fiction and that stereotypical landscape representations, mired as they are in a duplicitous history, are inadequate for expressing the complex technological, consumerist, environmental, geopolitical, and social issues affected by globalism. In her gallery-sized drawing installation Translocation and Overlay (2014) at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at the University of California Santa Barbara, Los Angeles multi-disciplinary artist Fran Siegel explored the site of Santa Barbara as a microcosm for promoting an alternative, critical visualization of the landscape for this milieu.

Fran Siegel, Translocation and Overlay, installation view, 2014. Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on vellum; and porcelain. Collection of the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara. Photo: Tony Mastres.

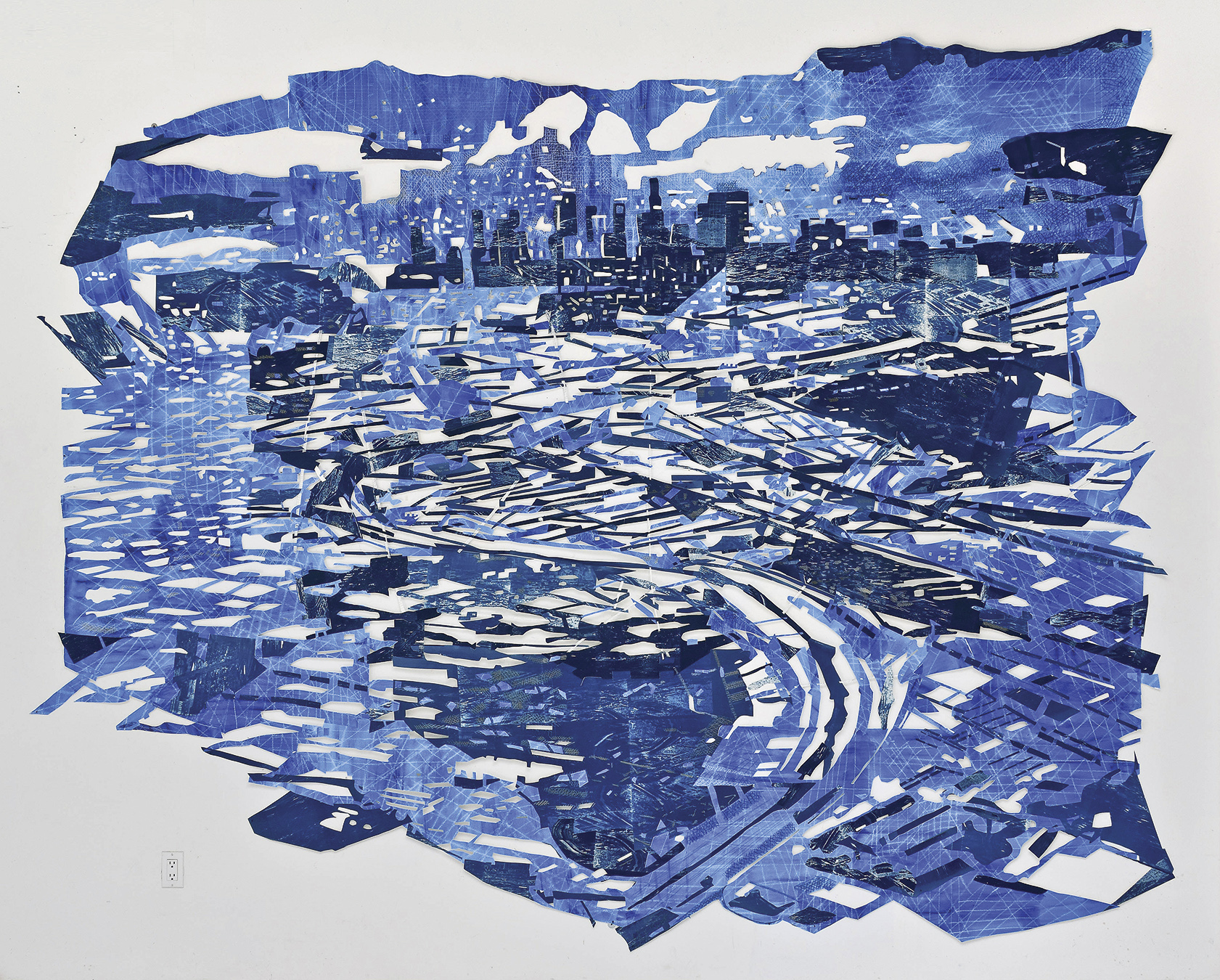

Siegel’s earlier monumental Overland works (2007–13) reinvigorated many of the visual languages that have captured the experience of urbanity. Large irregularly shaped map-like wall reliefs and room-sized installations of 3D “drawings,” these works express space as both sprawling and intimate, fluid from inside to outside and the reverse. Using drawing media like colored pencil and inks atop intricately layered and incised collage materials, including cyanotypes and translucent drafting films onto which photographic images are traced, Siegel constantly shifts between abstraction and figuration and maintains a lively dialogue between drawing, sculpture, photography, and maps. Fragments of cityscapes, endless grids and diagonals of streets and freeways, all from multiple perspectives, mingle with bold geometric and organic patterning, delicate traceries, and palimpsests. The use of blueprints connotes the perpetual construction and reconstruction of city spaces, underscoring a sense of continuing transformation. Teeming marks activate the surface and assert the personal in relation to the vast, linking memory and sensations with documentation and also suggesting incessant human movement through space. Cuts in the strata of her materials reveal the wall beneath, violating the pictorial illusions of representation and recalling Lucio Fontana’s slashed and punctured canvases of the 1950s, which were made partly in response to postwar devastation. Siegel’s overall approach to the Overland artworks also invokes the phenomenon of unstretched painting in the 1970s in the United States and Europe, which proposed that entire walls or rooms constituted a widening frame or context for a painting. In resurrecting such radical moments in art history and in embracing heterogeneous formal issues, Siegel renders the contemporary urban landscape as fragmented, porous, unbounded, unstable, and discontinuous—an expansive network of conflicting but connected systems, past and present.

Fran Siegel, Overland 16, 2013. Cyanotype, ink, pencil and pigment on cut paper; 96 × 140 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Lesley Heller Workspace, New York.

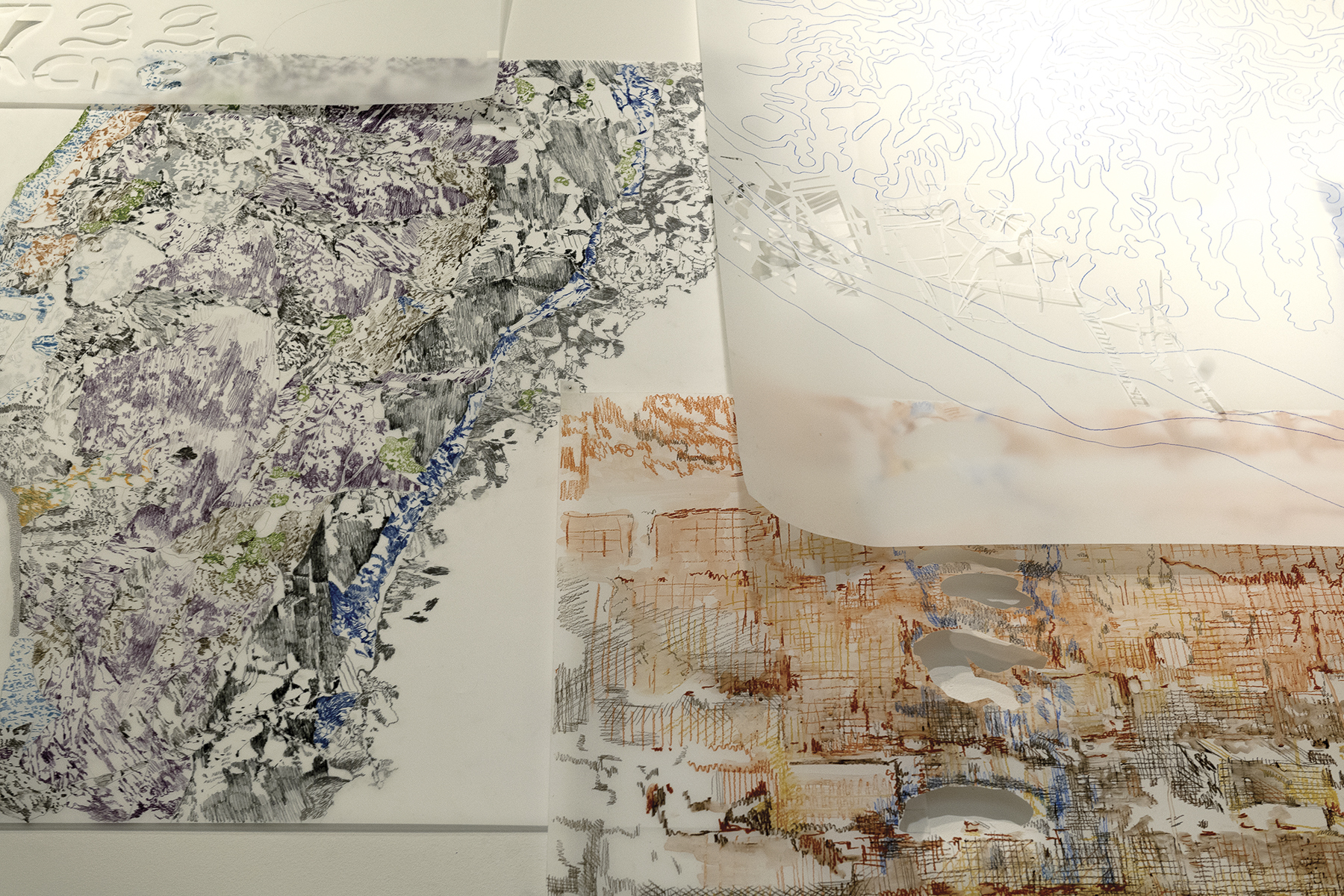

Translocation and Overlay, the culmination of Siegel’s yearlong residency at UCSB, eschews the single, self-contained artwork of Overland in favor of an extensive, interchangeable arrangement of drawings to further explore this understanding of the emergent urban environment. As in her previous work, notions of ephemerality and the ever-shifting nature of the landscape are reinforced by her formal choices and juxtapositions and stratifications of visual imagery—in this case, by working in an accumulative, patchwork fashion with fifty overlapping 4-by-4-foot translucent vellum sheets, which were intended to be recombined or reconfigured in future venues to invite different readings. The ideal material for tracing photographs, highly portable, and adaptable to diverse imagery and stylistic approaches, the vellum allowed the artist to interweave and overlay imagery from the past, such as period maps and photographs, with past and current visualizations of sociological, ecological, cultural, and commercial concerns and information.

The artist began her investigation by conceiving of a method for collecting visual data through defining an overarching thematic framework that would allow her to focus on the non-fixed characteristics of the location. For Siegel, Santa Barbara was an ideal location for a study of contrasts, especially for its beautiful utopic setting and highly planned character in relation to transient or fringe populations, like homeless people or migrating Monarch butterflies. As part of her research, Siegel communicated with students in the geology department at the university, an archivist from the historical society, and the director of the UCSB Map and Imagery Laboratory. From these “participants” she obtained information, maps, and archival photo documentation of the region concerning early Native American and Spanish settlements, topography, rock distributions, population dispersals over the years, past and current city layouts and planning, catastrophic fires, earthquakes, drought, oil spills, social changes, and economic development. In addition to taking hundreds of aerial photographs of the coastline between Los Angeles and Santa Barbara, which were the basis for nine of the drawings, her meanderings through the city and its environs produced myriad photographs of natural and human-made landscape features—from swimming pools to chaparral. Returning to her studio in San Pedro, she traced the photographic imagery in pencil, paint, and ink on the vellum, interpreting each subject variously—expressively, abstractly, or figuratively.

Fran Siegel, Translocation and Overlay, installation view, 2014. Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on vellum; and porcelain. Collection of the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara. Photo: Tony Mastres.

Displayed in the installation, the choices of paper and color and the wide range of marks and cutouts promoted multiple effects and associations important to realizing Siegel’s alternative approaches to landscape representation. As a stylistically diverse group, the drawings suggest that there is no single correct way to describe landscape, no progressive linear narrative. Some employ pointillism, exquisite cross hatching, and designs recalling Australian Aboriginal paintings, in which land forms and bodies of water are described abstractly by dots, dashes, and wavy lines, and develop into “maps” reflecting an intimate, experiential knowledge created by combining “dreamtime” with traveling through the landscape itself. The density of miniscule marks in many of the drawings seemed to mimic the mechanical ben-day dots or pixels from commercial and digital printing, referencing and confirming Siegel’s appropriation of photographic media as the primary means of accessing information about nature and space. Illustrational pencil renderings of birds, animals, and of local attractions, like the Santa Barbara Mission, are part of the mix and evoke the Western pictorial tradition. Owing to the graphic media, subtle shades of gray and black predominate, but soft blues, ochres, browns, greens, and reds, created by colored pencil and impressionistic ink washes, provide a naturalistic counterpoint to replications of landscape features like water, vegetation, and rock formations. Cloud and wind imagery, animated by abstract patterning and gestural marks, contribute to the overriding sense of constant movement in the landscape, synergies vibrating throughout, and the important connections between the elements in the evolution of the location. Functioning somewhat like skin that hints at the mostly non-visible veins and arteries beneath, the semi-transparent vellum allows rhythmic waves, gridded street layouts, cellular structures, and Native American basket weaving to be glimpsed in lively play with one another in the museum installation, suggesting underlying systems and commonalities. The pale paper and delicate traceries also impart a ghostly or dreamy sensation, supporting not only the imaginative nature of the project but also the fugitive nature of history and perception. Underscoring the importance of excavation in the process of disclosure, surgical-like incisions in many of the drawing surfaces take the shapes of competing interests or ecological occurrences—such as cutouts of erosion lines in drawings of the coast from dated photographs.

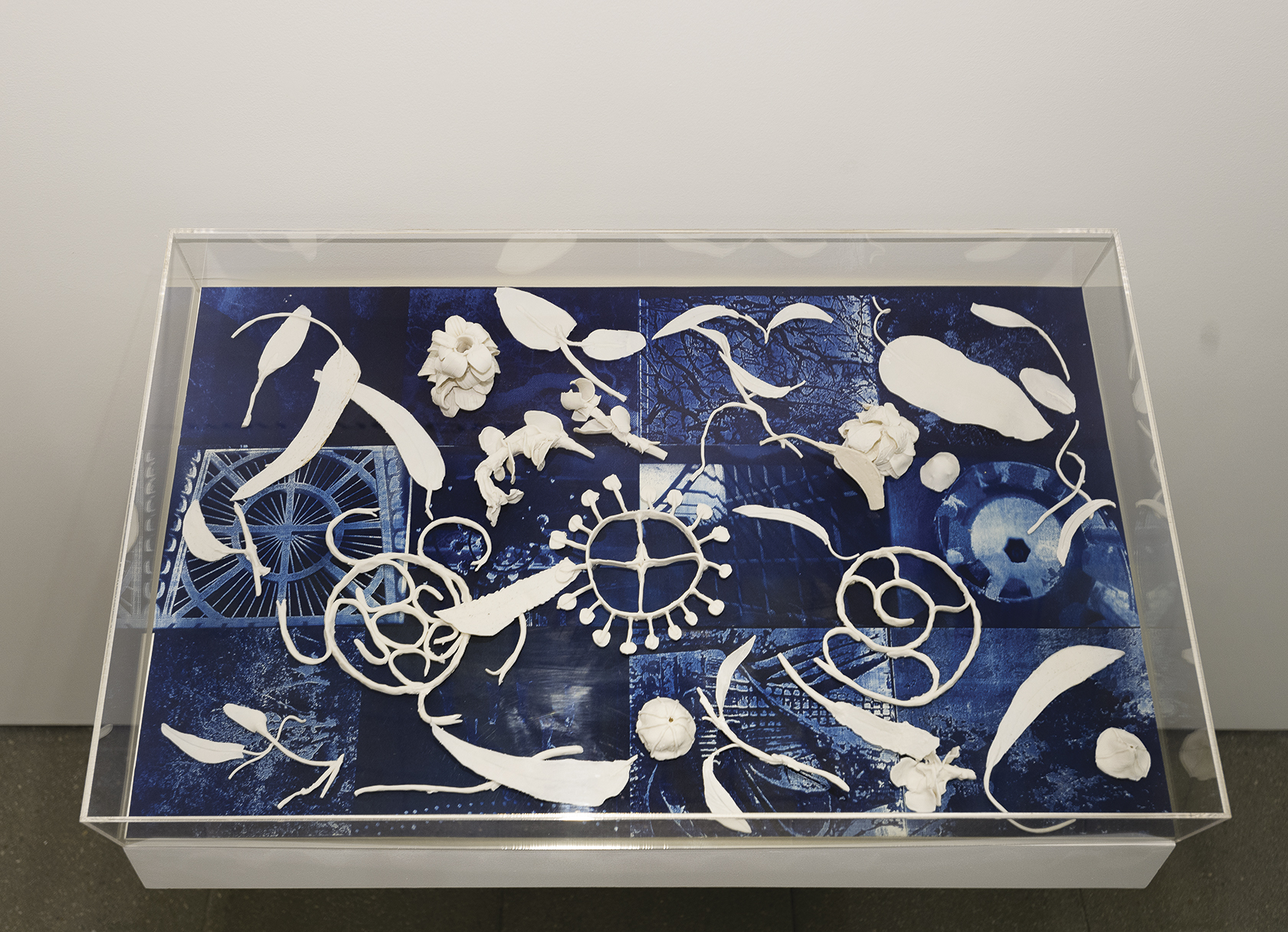

Although the drawings are individually poetic, evocative, and aesthetically satisfying, ultimately Siegel’s engagement of the gallery space and the placement of the drawings achieved a critical interrogation of traditional landscape as defined by Mitchell. Drawings arced over doors creating a sense of flow, of leaving and returning, while the soaring space infused the installation with buoyancy and possibility. The total use of the space emphasized the organic, non-sedentary, spatially disorienting, and non-traditional qualities of Siegel’s interpretation of landscape. Organized around a “spine” of nine of the aerial coastline drawings, which emphasize the co-dependence of Santa Barbara and Los Angeles, were groups of land, sea, water, and fire images. These were arranged rhizome-like, crawling and spreading from floor to ceiling. Without traditional framing devices or, for that matter, foreground or background, the land (or “place”) can be seen as an event with no fixed coordinates and ever changing horizons, transformed and affected by whatever moves through it. Siegel’s notion of terrain or earth is haptic, decentered, and non-hierarchical; the creatures that live and breathe here, the weather, disasters, and all other facts are produced equally. Evocations of the microscopic coexist with macroscopic panoramics. Nature is often posed in tension with urbanization: this particular arrangement placed fire drawings as if “blending into” water drawings—a reminder of the relationship between the two in Southern California, where droughts can be monumentally destructive to inhabited areas. Yet swimming pools are ubiquitous, as we see by dots crowding an abstract view from above. Peering from underneath a cutout of an oil spill was a Chumash basket pattern, reminding us that resource exploitation required the decimation of Native tribes as well as the natural environment. Scenes of leisure activity, such as shopping areas, zoos, and traveling circuses symbolized by an elephant, overlapped a scene of a Depression-era hobo encampment and shared proximity with an image of homeless persons’ shopping carts and a gold painted map delineating land divisions and ownership. Through these placements and juxtapositions, Siegel acts as a kind of visual anthropologist, revealing unseen relationships, interdependencies, and oppositions. In this portrait, the implication is that cities are places where past and present, nature and culture, and differing social groups interact and collide, often antagonistically. Further inviting anthropological readings, the artist created creamy white porcelain artifacts based on leaves gathered at the nearby butterfly preserve, mission chandeliers, and Chumash designed items. These were displayed in a cyanotype-lined vitrine. In another instance, a porcelain facsimile of a stratigraphic map of a mountaintop area renowned for its bohemian activity is both a tabletop abstract sculpture, composed of delicate, organic swirling ridges and channels, and a 3D elevation map. These playful, museum-like displays enfold the natural and transitory within the city’s historical and cultural fabric.

Fran Siegel, Translocation and Overlay, installation view, 2014. Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on vellum; and porcelain. Collection of the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara. Photo: Tony Mastres.

Originating as a Spanish mission outpost, the city of Santa Barbara was organized feudally to serve the colonizers’ interests, with large ranches on the outskirts and the Church, represented here by an image of the mission, at the center. City planning depended on the grid to keep political structures and interests intact and to control goods and services. Siegel has described the town today as a “gridded old world fantasy,” a kind of atavistic utopia secluded from the dysfunction of Los Angeles. In its re-imagination of the city as an ever-evolving narrative of unearthed visuals and subjective sensations, and its appeal to memory, signs, and desire, Translocation and Overlay recollects Italo Calvino’s hallucinogenic travelogue Invisible Cities. As Marco Polo spins rapturous successive tales for the Great Khan, the reader is dazzled with infinite, fantastically layered perspectives, philosophical conundrums and assertions, a collapsing of time and space, and a seemingly endless polychromed array of signs and symbolisms:

From each city described to him, the Great Khan’s mind set out on its own, and after dismantling the city piece by piece, he reconstructed it in other ways, substituting components, shifting them, inverting them…you cannot say that one aspect of the city is truer than the other.3

…[I]n his dreams now cities light as kites appear, pierced cities like laces, cities transparent as mosquito netting, cities like leaves’ veins, cities lined like a hand’s palm, filigree cities to be seen through their opaque and fictitious thickness.4

The city doesn’t tell its past; it must be revealed and discovered through a thick coating of images and signs. Siegel’s installation, with its kaleidoscopic aesthetic pleasures, mutability, proliferating associations and provocative questions posed, seems imbued with Calvino’s poetry. Like Invisible Cities, it embraced the importance of renouncing familiar visual language and structures to fully probe the nature of civilization. The inclusion of the personally observed and recorded, combined with maps based on political and economic imperatives, historical and natural images, and data, invited many possible interpretations concerning one’s position in the landscape—superseding the traditional landscape with its singular gaze. Siegel’s excisions and transparencies exposed repressed or erased information, recovering memories and unbinding the city from totalizing or progressive narratives. For the city, in Calvino’s words, is “made only of exceptions, exclusions, incongruities, contradictions.”5 Both the writer and the artist offer instead a splendid array of scenery—from nature’s realm to cathedrals and slums. Calvino’s perspicacity was borne out in a contemporary sense of instantaneous access and global movement, and Siegel partakes of his vision of geography as inventive, uncontainable, always in the process of becoming.

Fran Siegel, Translocation and Overlay, installation view, 2014. Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on vellum; and porcelain. Collection of the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara. Photo: Tony Mastres.

The kind of dreamy mélange of images so prominent in Calvino’s text and in Siegel’s installation also characterized Walter Benjamin’s theoretical writings for the Passagen-Werk (Arcades Project), and some of the most critical aspects of Siegel’s work come into focus through comparison to Benjamin. Her montaged visualizations of diverse landscape elements embody Benjamin’s statement in an earlier essay on Naples: “One only knows a spot once one has experienced it in as many dimensions as possible.”6 Author Susan Buck-Morss further describes the importance to Benjamin of producing many images simultaneously to fully assess the past and present:

Benjamin was…convinced of one thing: What was needed was a visual, not a linear logic: The concepts were to be imagistically constructed, according to the cognitive principles of montage. Nineteenth century objects were to be made visible as the origin of the present, at the same time that every assumption of progress was to be scrupulously rejected.7

…Such images were the concrete, “small, particular moments” in which the “total historical event” was to be discovered…8

For Benjamin and Siegel, the present is to be understood and expressed as an accumulation of historical mementoes. Benjamin’s wanderings through the Paris arcades—reprised by Siegel’s roaming, historical imagery and fashioning of faux artifacts in Santa Barbara—produced a huge inventory of archaic sights from nineteenth-century fashion, consumer goods, artifacts from the colonial Empire’s plunder, architecture, kitsch, literary figures, and urban phenomena. Montage, the reassembling of fragments from many sources, became the most important form of representation in building the theories of the Passagen-Werk. Not guided by any rigid structures, montage for Benjamin produced a dream-like state in which images and short texts appear and disappear, always incomplete and incoherent. Upon awakening from this “dream,” these phantasmagoria, readers or viewers could develop conscious knowledge about modern Industrial Commodity Capitalism, bourgeois class rule, “the eternal verity of Western imperial domination”9 and its utopic dream fulfillment machine; a new freedom would critically emerge from this recognition. Siegel’s use of a montage format and soft, spectral visuals of forgotten sights and events encourages similar critical readings into the conditions of the present city. Population density drawings, for example—when seen in orchestra with oil rigs, plans for earthquake redevelopment that altered the city’s original character to a Spanish Colonial style, and images of leisurely bike rides—suggest early city planning that reinforced the city’s utopic, escapist fantasy of itself. As that romantic image began to predominate, the town became increasingly exclusive, and today Santa Barbara is so wealthy it does not qualify for federal funds for affordable housing. Additionally, the faintly discerned cutout words Gap, Sycamore, and Tea refer to three epic fires in the region, but in a visual pun, Siegel recasts these fire names as the corporate logos that share the names. In this way, destruction is identified with commercial real estate development and consumer capitalism, not simply with acts of nature. Much as Benjamin sought to “demythify the present”10 and question Nazi totalitarianism as an outgrowth of commodity fetishism, Siegel’s juxtapositions seem to extend Benjamin’s insights into challenging the current paradigms of capital-centric development that are designed to benefit special financial interests. Santa Barbara is, of course, a metaphor for any urban area.

Fran Siegel, Translocation and Overlay, installation view, 2014. Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on vellum; and porcelain. Collection of the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara. Photo: Tony Mastres.

The free association of time, space, cultures, events, and locations in Siegel’s installation is also indebted to Robert Rauschenberg’s ground breaking, semi-transparent photographic transfers and translucent surfaces interlaced with gestural marks, from the late 1960s through the 1990s. In Rauschenberg’s collages, the autonomy and authority of the photographic image was infringed upon and could not be perceived in isolation, but rather was in a dynamic exchange or flow with a universe of appropriated and subjective images. The singular gaze was deconstructed and replaced by considerations of the connectivity between images and icons. These works often carried unsettling political themes, for example, Earth Day (1970) shows a grand image of an American eagle surrounded by scenes of polluted landscapes. Siegel’s multi-faceted presentation of the landscape relies on such Rauschenbergian tactics whereby history and contemporary experience are forced into in an active relationship of the kind Benjamin proposed in order to challenge powerful biases and entrenched meanings.

The most illuminating political aspect of Siegel’s project might derive from the understanding of urban space as perpetually evolving from heterogeneous natural, social, and economic interests. Dynamic, multifaceted, rejecting any single paradigm as sufficient—subjective or objective, historical or contemporary—for representing the landscape, Siegel disunifies the landscape as a monolithic scenic representation. Her working methods as a roving outsider and the discursive nature of the exhibition corroborate Deleuze and Guattari’s theories of rhizomes and nomads in texts such as Nomadology and the War Machine and A Thousand Plateaus. They articulate ways the State repressively administers and controls populations by ghettoizing and disarming populations. Nomads who infiltrate from outside this State are able to resist and challenge the control of land by special interests.

History is always written from the sedentary point of view and in the name of the unitary State apparatus…. What is lacking is a Nomadology, the opposite of history…. Make Rhizomes, not root, never plant! Don’t sow, grow offshoots. Don’t be one or multiple…. Be multiplicities…. A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things…a stream without beginning or end that undermines its banks and picks up speed in the middle.11

…[T]he rhizome pertains to a map that must be produced, constructed, a map that is always detachable, connectable, reversible, modifiable, and has multiple entryways and exits and its own lines of flight. It is tracings that must be put on the map, not the opposite. In contrast to centered (even polycentric) systems with hierarchical modes of communication and preestablished paths, the rhizome is acentered, non-hierarchical…12

Fran Siegel, Translocation and Overlay, installation view, 2014. Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on vellum; and porcelain. Collection of the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara. Photo: Tony Mastres.

The nomad, then, like a spreading underground rhizome, becomes the means of deterritorialization, flow, and freedom from borders or enclosures, while the sedentary would be tethered to power, exploitation, possession, and assigned identities. In stressing movement through space by transient communities such as Monarch butterflies and the homeless, Siegel introduces notions of flight and freedom as aspects of locations. A rhizome is characterized by detachability, modifiability with multiple entrances and exits, much like Siegel’s installation at AD&A itself: we can enter it from any direction and the diverse information can be infinitely reordered. A rhizomatic space contains disparate matter and provokes sensual rather than rational responses. Deleuze and Guattari’s approach to the history of civilization is to perceive it anarchically, as a process that resists grand narratives or a single fixed perspective. By rendering the present as a simultaneous product of the past, by modifying and augmenting maps and changing the orientations of the extensive non-linear installation, Translocation and Overlay hews to what Deleuze and Guattari theorize as a “schizoid” view.

Pressing current issues of immigration, eco-collapse, population dispersals from wars, economic conditions, and political redistricting will require the imperial landscape of maps and highly codified pictures, which impose the illusion of a unified, “natural” space as described by Mitchell, to be endlessly redrawn. As Siegel has so compellingly demonstrated, re-envisioning and reconceptualizing the landscape can embody an authentic naturalness—as animals and humans have always roamed through spaces for survival and new communities have sprung up out of necessity. Challenging the controlled framework of perspectival rendering or the stereotypes imposed by ideological agendas, the artist has responded to present urgencies via an open-ended and unrestricted contemporary vision of the landscape with vast possibilities for the future.

Constance Mallinson is a Los Angeles-based painter, writer, and curator.