In 1997, Ellen Birrell and Stephen Berens produced the first issue of X-TRA with co-founders Jan Tumlir and Jérôme Saint-Loubert Bié. In the following interview, they recount the intertwined histories of the journal and Project X, which started out as a series of artist-organized site-specific exhibitions.

X-TRA Founders Stephen Berens and Ellen Birrell with Brica Wilcox in Santa Paula, CA.

Brica Wilcox: Thanks for joining me to talk about the beginnings of X-TRA and Project X. You’re in the middle of the fifteenth year of X-TRA. A lot has happened! Could you go back to the beginning and tell me how everything started?

Stephen Berens: Maybe we should start with how we came to be living in Los Angeles. In the 1970s I was an artist and curator in Florida, curating by mail order. Meaning I would write artists a letter, they would send me slides, I would pick work out, they would send the work, and I would install exhibitions at the Florida School of the Arts, which is not as fancy as its title would imply. After doing this for a few years, I decided I needed to live in New York or Los Angeles. I got a phone call from a former professor who lived in Los Angeles and he had a house I could rent for $125 a month. That’s why I moved to Los Angeles in the fall of 1980. I also know how Ellen got here. I was working at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1981. Ellen Birrell and David Bunn, now her husband, had applied to the MFA program at UCLA. I called up, I think it was Ellen’s mom, to inform her that David had been accepted to UCLA.

Ellen Birrell: David and I had been living in Boston prior to coming to Los Angeles; we had started a small artists’ press there. We did various kinds of lithographic limited edition things and small artists’ books, keeping body and soul together with bad day jobs—from house painting to filing. We came out here when David got accepted at UCLA. While looking for a place to live, we were generously invited to a party at a soon-to-be friend’s house. As I approached the house, there was Stephen flat on his back in the driveway, completely, gloriously, Rabelaisianly drunk. I thought, “Who is that guy?”

Stephen and his partner, Elizabeth Bryant, and David and I became very fast and close friends and have been so, I am proud to say, ever since. The four of us shared two studio buildings in downtown Los Angeles, and in the second one, on Willow Street, Stephen and I would often have lunch or coffee in the afternoon, talking about what in the art world works and what doesn’t work. This was in the early 1990s and there was a big economic “correction” going on in the city.

SB: There had been quite a boom in the art market in the late 1980s and a wave of new commercial galleries opened in Los Angeles. But with the economy entering a recession in 1990 many of those same galleries began closing. At that time a friend, Christian Mounger, was working at a community college called El Camino. He asked if I was interested in organizing an exhibition with him. So, we organized an exhibition called Objects Objet, and included the work of Elizabeth Bryant, Anne Walsh, who’s now up in Berkeley, Jorge Pardo, and me. It was just at a small community college gallery. The interesting thing was that at the opening, there was a huge crowd. A lot of artists showed up at that opening.

BW: This was in 1991?

SB: Fall 1991, I think. It was sort of like, “Oh, you could do an exhibition anywhere. It doesn’t have to be in a commercial gallery anymore.” You could do something somewhere else and people would come. People are interested. It reminded me of my experiences making and showing art in the 1970s, where the point of exhibiting was mostly so that other artists could see what you were doing. EB: A community college gallery became a place.

SB: For that one month.

BW: That revelation was the inspiration to try to do something similar in comparable institutions?

EB: That was a big thing for Stephen, but I was less aware of that. In my practice, I’d gone from working with photography to site-specific installation. My issue was that it was crucial for work like this to be documented and written about, because you really need to be there, there’s no object afterlife. With the contraction of overall showing opportunities, I felt my practice being slammed both from not making a conforming object and from not having a vigorous press to enact a critical response to the non-conforming object. These were the kinds of things coming up in our studio conversations.

SB: As Ellen and I thought about organizing exhibitions we looked at how nonprofit galleries operated. Having a space meant you had overhead expenses: rent and salaries. So, of the money you raised, maybe 20% of the total operating funds actually went into the exhibitions, everything else was overhead. We felt if we could get rid of the overhead, we could do exhibitions much more easily. The idea was the same thing that happened at El Camino. Go to locations that already had an infrastructure: gallery, staff, money for mailing, the ability to keep the gallery open. We could just inhabit those spaces.

EB: What they didn’t have was adventurous programming.

SB: They didn’t have the programming that we were interested in.

Project X Paper for The First Show, October–November 1992, Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, Orange, California. 16 pages, newsprint.

EB: At this point, we made up a Project X letterhead, gave each other titles, wrote official letters on the made-up letterhead, and started to pitch ourselves as a group who would come and organize a temporary exhibition in their space.

BW: It’s interesting that in all of the Project X exhibition papers, you state that you’re not a curating venture and talk very clearly about the fluctuation of the participants coming together in situ, with each project primarily being about the group’s decisions on what to produce.

EB: Right, we imagined our identity as Project X as being more like coordinators. The shows came about not as curating, but more like a chain letter. The founding insight of every one of the shows, for me at least, was an interest in something particular about the actual locations: the context of the space, the social and cultural context. The way Stephen and I started, we would each think about the space and then, for whatever set of reasons, come up with a first artist to invite. Then we’d offer to that artist the opportunity to invite yet another person. That person, if we had enough room, could invite a third person. It was a decentered collection of people. That provided a fascinating way of making networked connections between artists. One of the exciting things about this process was gathering people who had equal stakes in what was going to be in the room. It was an extraordinary shared ownership of the final product of the show. Being curated into a group show by a visionary curator is great too, but many group shows, organized around more casual or pragmatic connections, can feel like being part of a list, and in that list, an artist can be hidden in plain sight.

SB: It was also a reaction to some of the curating going on and the type of grants that were available. At that time, there were things that would basically be an open call. Artists had to submit a proposal and only after you developed your idea for that particular exhibition would they tell you, “Oh, yes, you’ll be in the show.” It felt like they did not trust artists. Rather than say, “This is the space. This is the idea for the show. You can do whatever you want. I trust you.” For me, one of the important things was believing in the artists. The first place where we proposed an exhibition was The Guggenheim Gallery at Chapman University; it was such a great name. During the time we were planning, I was in London and woke up in the middle of the night with the idea that for our first show as Project X, we could do the same thing that the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) did for its first exhibition. We could call it The First Show. In fact, we could use their catalog cover and introductory text, and just X out everything that didn’t apply to us for our catalog, which is what we ended up doing.

BW: At the beginning of MOCA’s version, there are so many “thank yous” related to all the funding. In the Project X version, I noticed Eli Broad is X’ed out very early on.

EB: The First Show at MOCA, in 1983, was all about the collections they were either getting or courting. The names on the front were those of collectors; not of artists.

SB: We replaced the collector with the artist. Otherwise, there was a lot of stuff that did apply. So, we left all that in place. We did agree with the basic idea of “having exhibitions where you consider art as a witness to and expression of its time.”

EB: What we figured out with Chapman constituted a loose template for subsequent Project X shows. Our pitch to the institution was that we would organize a show with a documenting publication and they would pay to keep it open and keep the work safe. Their only other cost was $1000 paid directly to the printer because that’s what it cost to produce 1000 copies of a sixteen-page offset newsprint publication. Our routine was to install the show and set the reception for a week into the run. During that week, Stephen and I would collect our 4 x 5 cameras and all the Polaroid film we could find and document the work in situ. The exhibition invitation to each artist included a page in the publication, encouraging them to do something direct to print. In almost every case, we would also invite a writer to write something in response to the space, the group of artists, or the work; to contribute writing that, in their purview, was appropriate. It was essentially recognizing the writer as another form of artist-worker. Writing was really important early on. Everything for the publication was assembled that week, and by the opening, we would have the printed copy in hand to give away free. That was a real juicy thing. A thousand bucks and the institution gets a show and a free publication. As a maker of ephemeral site works, that solved a big problem for how I understood the art work: now it might have a life, a track record, a visibility beyond the direct encounter within the space.

SB: The First Show publication says, “Project X is a fluctuating confederation of artists who are, with this show, initiating a program of artist curated exhibitions, each to be accompanied by a documenting publication such as this one. Once again, it has become apparent that artists need to take control of the processes by which their work is seen and understood. If you have an idea or location, contact us.” It was certainly a collective beginning.

Project X Paper for Xtreme Research, February 1993, California State University at Los Angeles. 16 pages, newsprint.

BW: Xtreme Research from 1993 is one of my favorite of the Project X papers. Can you tell me about the exhibition at Cal State Los Angeles?

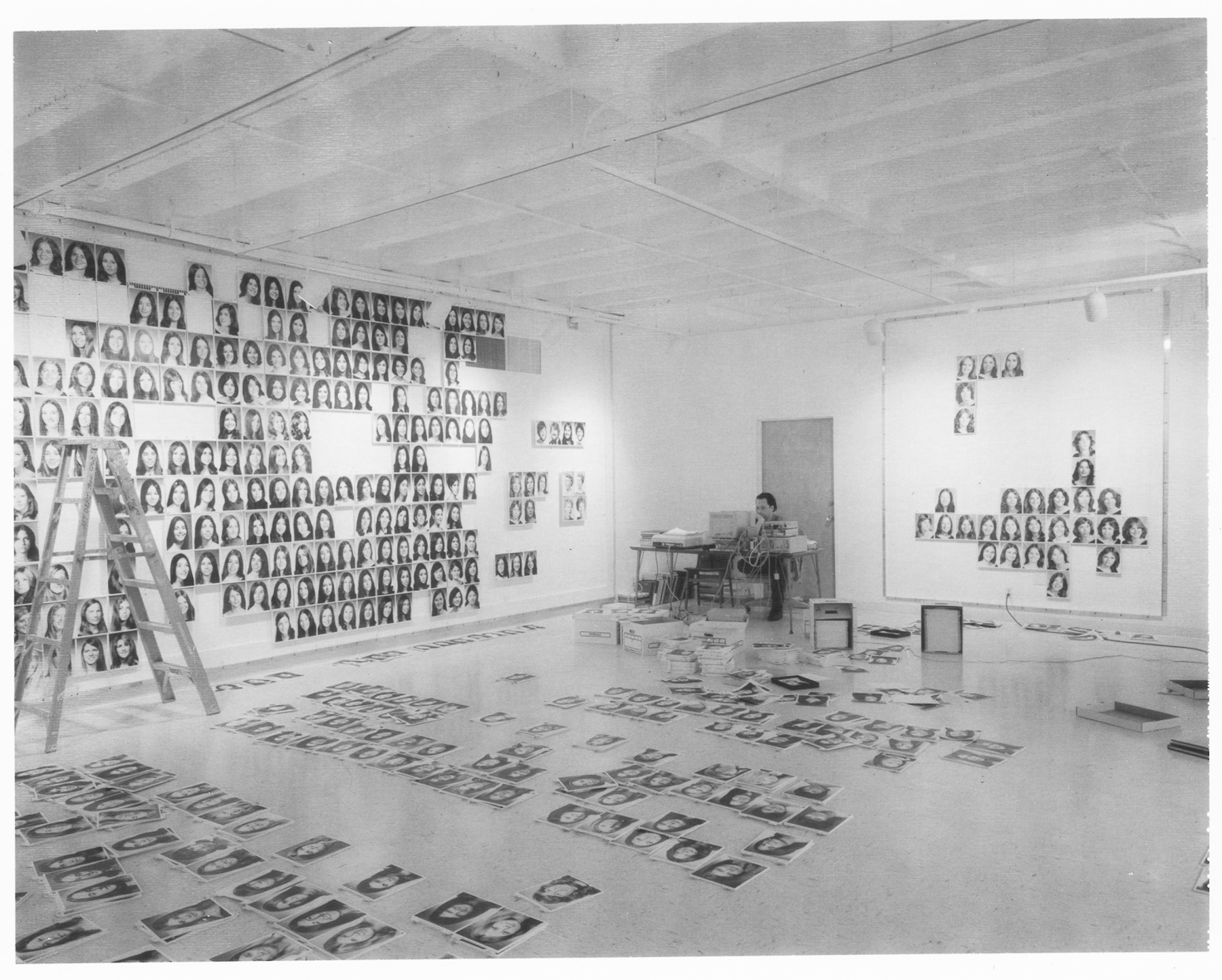

EB: It’s also one of mine. Mitchell Syrop started this particular way of installing his yearbook pictures there, actually using the gallery as a research site throughout the time of the show. Prior to this, he’d been hanging them in static groups.

SB: Mitchell not only worked there, he had graduate assistants work with him, as you would in a research facility. So we were able to use not only the facility but also the resources of the institution. I think that was an important thing. A lot of people could try different kinds of activities; people would try something different because the opportunity presented itself.

Mitchell Syrop, Mistaken Identities Project, installation view in Xtreme Research, February 1993, California State University, Los Angeles.

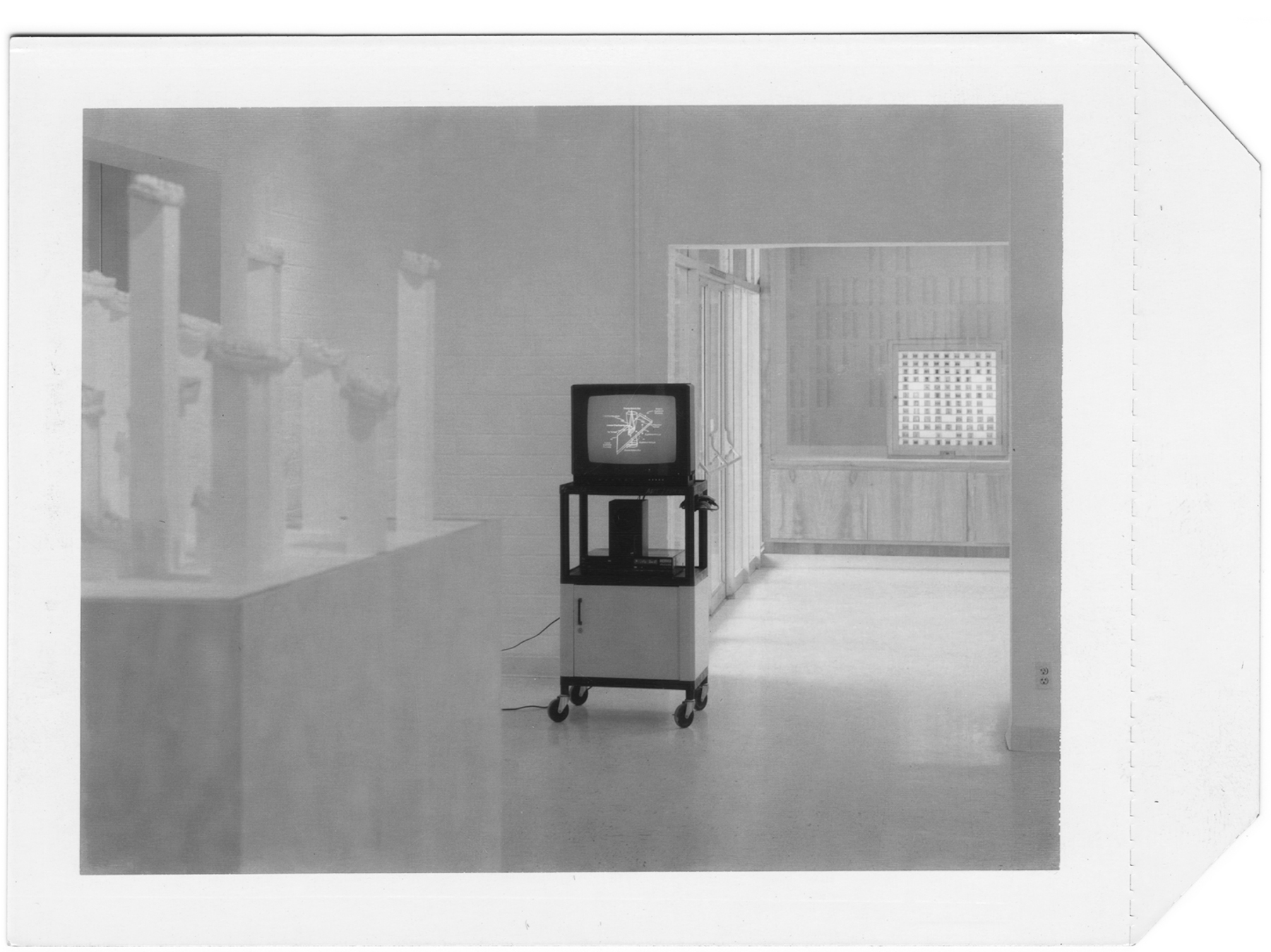

David Wilson, Geoffrey Sonnabend, Obliscence: Theories of Forgetting and the Problems of Matter, an Encapsulation, video, 1993. Installation view in Xtreme Research, February 1993, California State University, Los Angeles.

EB: David Wilson made a video with wonderful diagrams about a marvelously abstruse theory about memory. I seem to remember animations, and a lovely professional voiceover. These were great people who were using the model of research.

SB: Cal State Los Angeles had video production facilities, which were much different in 1993 than they are now. They produced what I believe was David Wilson’s first video. Also, David lectured as part of his piece.

EB: Yes, that was fabulous. The other thing is that in the case of Mitchell, he said, “I want to give half my page away to somebody else.” He shared his page with Cinthea Fiss, and of course she was working on something quite complementary to what he was doing. That was another case of this extended act of reaching out to another artist with a related practice.

BW: And continued that generous invitational style.

Installation view of works by Christian Mounger (left) and Eric Magnuson, in Suitably Appointed, September 21–December 14, 1993, Muckenthaler Cultural Center, Fullerton, California.

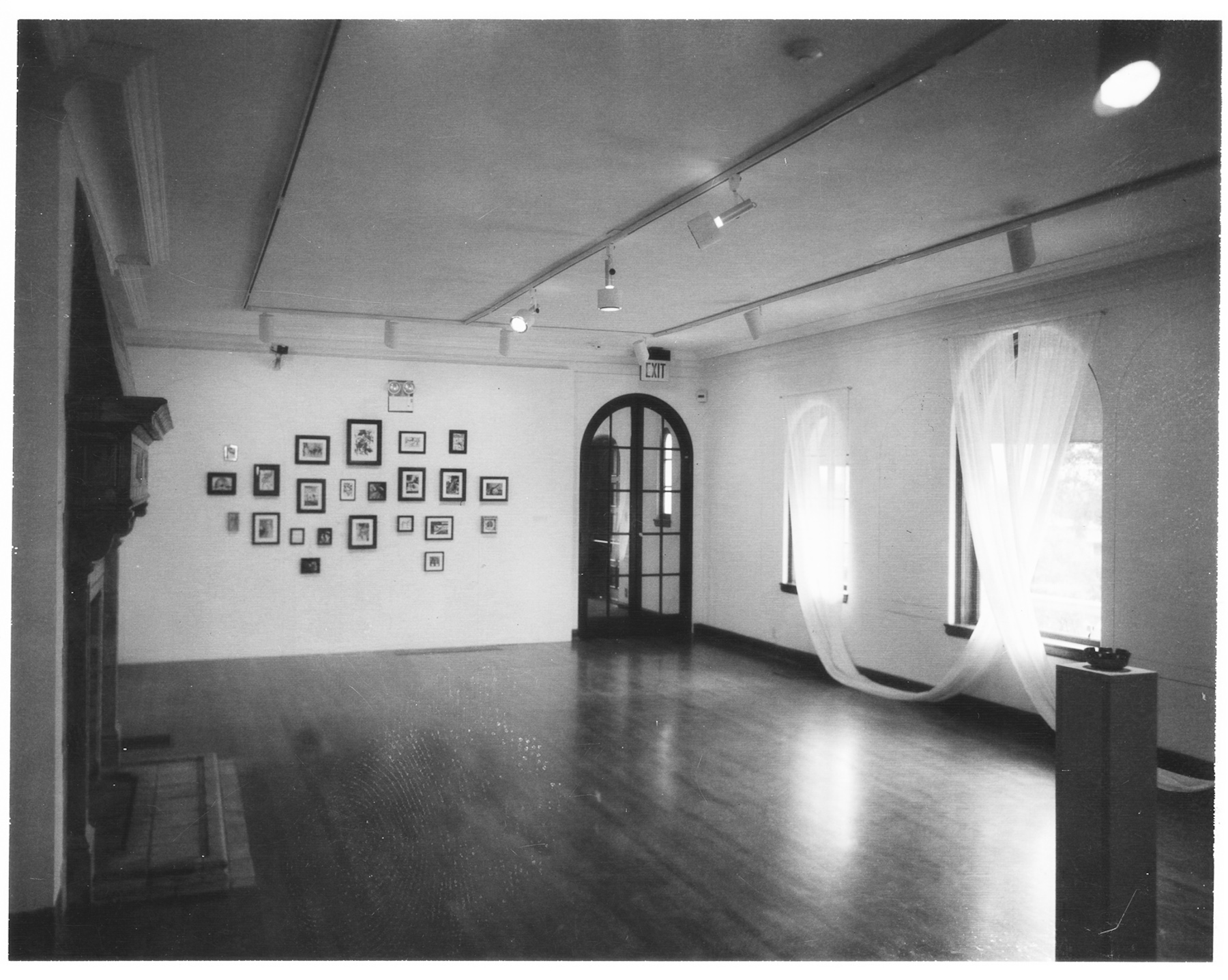

SB: Suitably Appointed, at end of 1993, was the first exhibition that Ellen and I just facilitated.It took place in a historic house, the Muckenthaler.

EB: It’s a landmark property, an old citrus grower’s house in Fullerton, which had been adapted into a sort of community gallery by lining all of the original surfaces with false walls. They had to do something with the electrical system that required them to pull all those fake walls out. Suddenly, the house was visible in a way that it hadn’t been for twenty or thirty years. We heard about this, and convinced the people who ran the Muckenthaler that this was a great opportunity to do a show about the house itself—or about what the house generates in peoples’ thinking.

SB: A lot of the work dealt with the domestic. People were making work specifically responding to that site. Renée Petropoulos made a kind of work that she’d never made before. Anne Walsh’s piece was a kind of piece that she had never generated before.

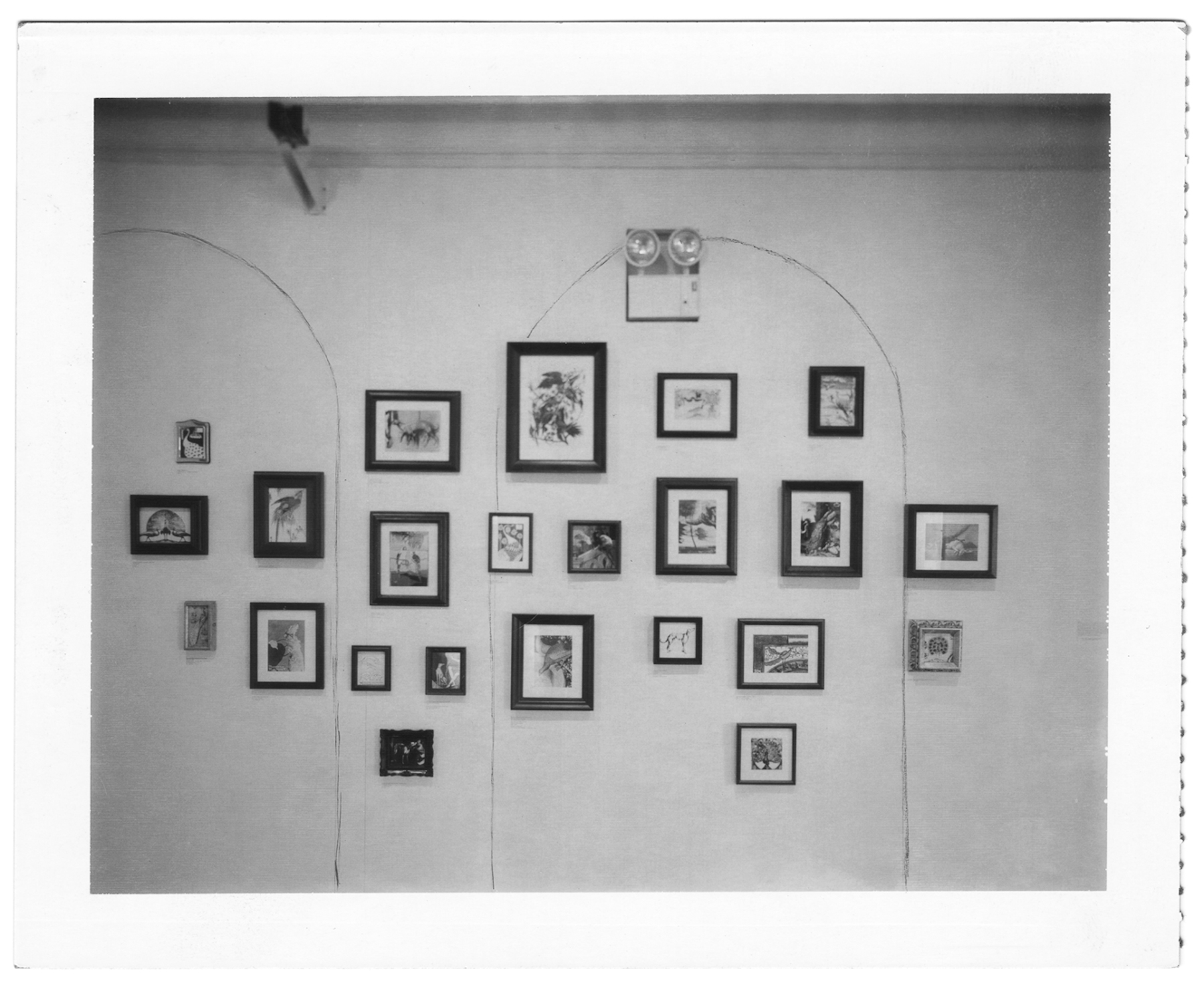

Installation view of Christian Mounger, The Peaceable Kingdom, 1993, and Renée Petropoulos, untitled,1993, in Suitably Appointed, September 21–December 14, 1993, Muckenthaler Cultural Center, Fullerton,California.

EB: That was a real breakout moment in this shared conversation about what is to be done in this show, in this place—the real question of both exhibition design and site specificity. Renée decides that she’s really attracted to the mission style revival architecture with the rounded barrel vault arches all through the house. Essentially, she does a line drawing in real scale of the entire house but shifts it, which meant that these chalk line drawings went throughout the entire exhibition space. It ends up being in the middle of everybody else’s work. Here’s a case in which a site-specific work doesn’t overwhelm anybody else but marks the context in a different way. It also evoked the displacement of the false walls with a kind of ghostly echo. I thought it was a really wonderful piece.

Eli [Pulsinelli], who’s still very much involved in X-TRA now, did this whole cutout thing. This was her first opportunity to work with us. For her page in the publication, she created a model of the Muckenthaler, with all of its interior decorative details, as a paper doll kind of a house that you could cut out and assemble. She traced in all of Renée’s drawings, which is really fun.

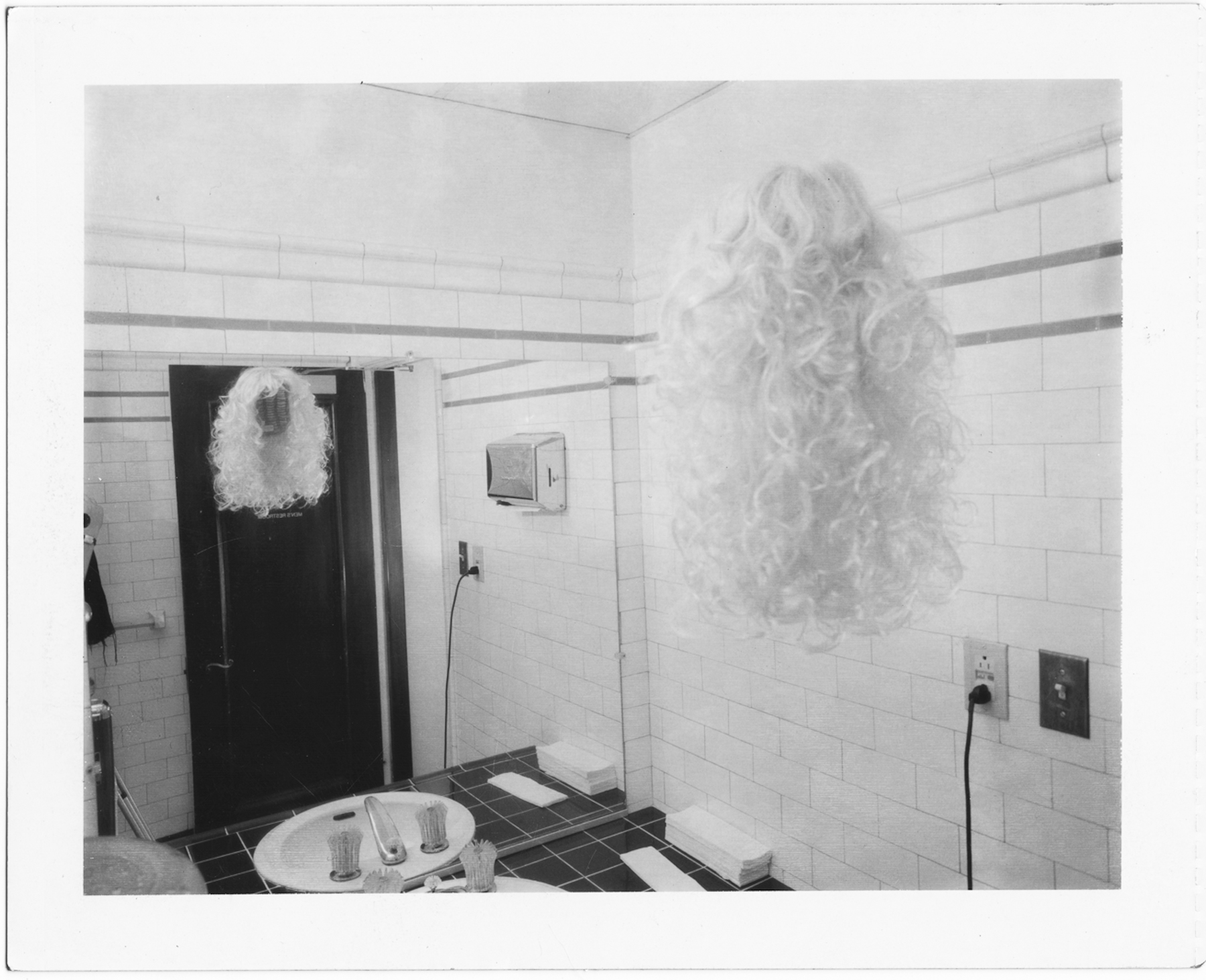

Anne Walsh, Men’s Restroom, 1993. Installation view in Suitably Appointed, September 21–December 14, 1993, Muckenthaler Cultural Center, Fullerton, California.

Anne Walsh’s piece, in particular, brought up some interesting issues about the use of the house as a community gallery, and some kind of arbitrary boundary about where art happens and doesn’t. When they converted the house to the gallery, they took the downstairs guest bathroom and assigned it as is the men’s room, and then they built a separate women’s room because they had to fulfill a set of building standards for a community center. When all of the interior walls came out, it was clear that the so-called men’s room was actually a nice little ungendered “powder” room. In facilitating the show, we were talking with the Muckenthaler people about whether we could we use all the original spaces of the house. At first, the answer was “No, no, no, those are off limits because they have to continue to function.” We did manage to convince them, and Anne installed her work in that old bathroom, which continued throughout the show to be used as the men’s room. She hung a fabulous long blonde wig in front of one of the mirrors.

BW: Was it on some kind of pulley so anyone could position it on their head?

EB: Absolutely, which was quite wonderful.

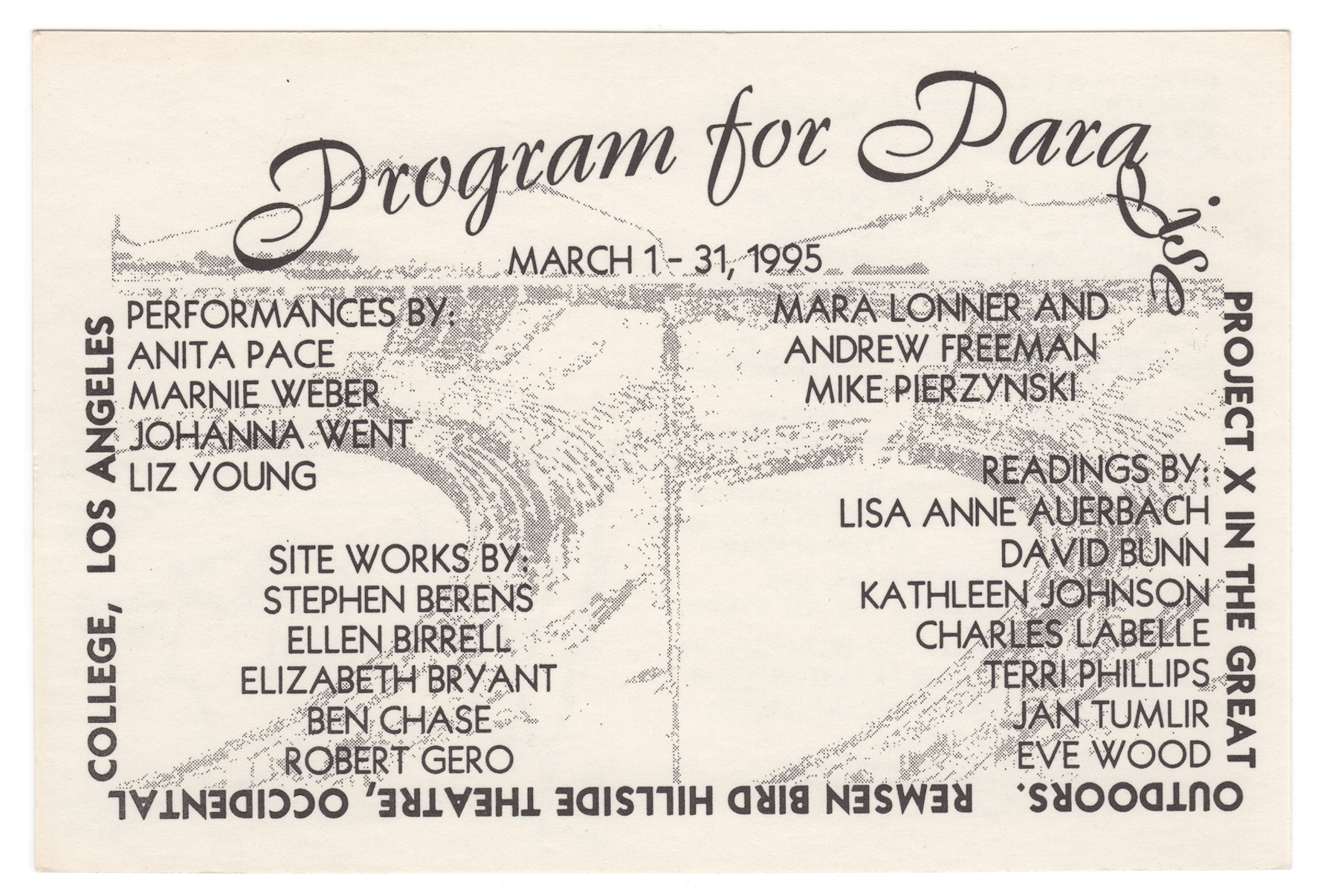

Exhibition postcard for Program for Paradise, March 1995, Remsen Bird Hillside Theatre, Occidental College, Los Angeles.

SB: I think the project after that was Program for Paradise, in 1995, at the Occidental College Amphitheater. It broadened the scope, in that it included a program of events.

EB: It had something like thirty people performing in the amphitheater.

SB: And we had a series of readings.

EB: Anita Pace with Mike Kelley organized all of the performance stuff, and David Bunn was very involved in the artist’s readings.

Polaroid from Ellen Birrell’s direct-to-print page in the Project X Paper for Program for Paradise, 1995. This self-portrait is a restaging of the 1873 portrait of Walt Whitman by Phillips & Taylor, Philadelphia, that appeared as the frontispiece for over twenty editions of Leaves of Grass. It was popularly thought that the butterfly just happened to light on Whitman’s hand at the moment of exposure, serendipitous proof that the poet was a “natural.” In the 1990s, the paper butterfly used in the portrait was found in one of Whitman’s books.

Stephen Berens, detail of Vista Points in Program for Paradise, March 1995, Remsen Bird Hillside Theatre, Occidental College, Los Angeles.

Marnie Weber, Beasts of Transgression, performance in Program for Paradise, March 1995, Remsen Bird Hillside Theatre, Occidental College, Los Angeles.

SB: And there was a very early performance by Marnie Weber, The Beasts of Transgression, with her singing “Cry for Happy.” We did the next project with the Armory Center in Pasadena, Pair-A-Sites, which happened over a three-month period in what they termed the “community room.” We were interested in the Armory Center because they basically divided their space in half; education on one half and exhibitions on the other half. This room was their only space that was public and used for both exhibition and educational uses. We were interested in that room. We organized three different exhibitions. One was—

EB: Charles Gaines and Cheryl Kershaw in December 1995.

SB: Which looked at the history of armories in America.

EB: The second was Diane Bromberg and Eve Luckring, in February 1996.

SB: Their exhibition was a problematic experience for me. Since it was a community room, it had to be used for functions other than just exhibitions. The Armory brought groups of children in there for orientations, among other things. Our projects had to be approved with these other events in mind. All of a sudden we were back to this point where we were losing a little bit of control. We go into an institution, we say we want to do this, and they say, “Oh, no, you can’t do that.”

EB: This was the threshold we were getting to with Anne’s piece in Suitably Appointed, but at the Muckenthaler we managed to finesse it.

SB: Originally, Eve and Diane’s plan was to put six inches of sand over the entire floor of this room so that when you left, a little bit of the room would travel with you, changing what is normally a mental activity into a physical one. Usually, you look at an exhibition and you take that experience home. In this instance you would actually take a little bit of the place itself home with you that would act as a reminder.

EB: I thought it was also a pointed reference to the fact that the community room is part of the educational function of the Armory, so this notion of a big sandbox in the middle of it made a reference to child’s play. Alternately the sand allowed the visitor to leave an indexical trace of their passage through the space, in my mind a poignant comment on how ephemeral most viewing experiences actually are in relation to the durable presence of the artwork, even if, as in this case, that artwork is both temporary and leaking. It was a nice conceptual address to what the community room aspires to do. But the Armory people were very concerned about dust from the sand and people having breathing issues.

SB: They were basically afraid of lawsuits.

EB: Nothing happened, except in their heads.

SB: We had to keep renegotiating. Originally the whole floor was going to be covered. Then they were going to have piles in the corner, but the piles were too big. They wanted to make a little sandbox in the center but that wasn’t approved. So in the end, there was a pile of sand three feet high and probably five feet in diameter, however it spread out.

SB: That’s it. That’s all they could do. It actually turned out to be quite beautiful. It’s this beautiful cone of sand. It’s sanitized. This is white-washed, flame-sanitized, and uniformly graded sand.

Diane Bromberg and Eve Luckring, direct-to-print page in the Project X Paper for Pair-A-Sites, 1996, ArmoryCenter for the Arts, Pasadena, California.

EB: About as sanitized as we could make the art be.

SB: The piece lasted, I think, two days.

EB: If that.

SB: I went with Eve the day afterwards and we did some photographs, and then Eve went back to photograph again the next day and as she arrived, they were sweeping it up. They said it was interfering in the space so they couldn’t allow it to stay. They were afraid that someone with asthma could still get sand in their face. As if a child couldn’t put dirt in their face outside of this room. In talking with people later it seems like what really drove the removal of the piece was that some of the people teaching there felt like it was too disruptive. Basically, the teachers were trying to talk to the children about the lessons, and the kids were much more interested in the pile of sand in front of them, so they couldn’t hold their attention.

BW: The sandbox is supposed to be outside for a reason.

SB: It was really a struggle to get these three exhibitions up. By 1995, the galleries were starting to reemerge. And as I said before, people coming out of graduate programs were not thinking about running a nonprofit space or even necessarily showing in one. The commercial gallery model was again becoming the preferred model, where somebody could sell something. With that, we started to see that the publications reached twenty times the number of people that the physical project did. They had a much longer life and a much bigger audience. That moment when people were willing to go anywhere to see something had passed. Los Angeles needed something other than another exhibition space, as exhibition spaces were opening every month. However, there still was no representative documentation of art being made and shown in Los Angeles, as most Los Angeles-based publications printed a few issues and folded.

EB: Coast, I remember getting one issue of Coast. Now Time was another. Both of these started out undercapitalized and with very high production values.

SB: The only one that was sustained to any degree at that time was Art Issues.

EB: Gary Kornblau’s Art Issues was an incredibly passionate embrace of abstraction, sensory pleasure, and visual pleasure in, to me, a primarily formalist historical sense, and very much against a conceptual agenda or a reading through of works. It had a celebratory aspect and a repressive aspect to it. Kornblau was training a cadre of writers who were then appearing in the Los Angeles Times, for example, or speaking about Los Angeles outside of Los Angeles in ways that were having significant impact. The writer for Artforum who was doing the 500-word reviews had apprenticed at Art Issues. I was seeing the power of criticism, the power of very convincing criticism, but occupying an extremely narrow bandwidth of what could be talked about. As the galleries began to reemerge, there was obviously more work being shown. The power of this critical digest of what goes on in Los Angeles coming only from one point of view seemed to be deadly and really scary to me.

BW: So in a way X-TRA was a corrective to a dominant voice that seemed limited and subjective.

EB: Yes. One of the things that goes forward from Project X is the sense of shared ownership of the content of the material. The plural editorial model of X-TRA is designed not to give any one seat at the table more control over what goes in. Now, it took us a couple of years to figure out how to make that work. We tried a bunch of different models.

SB: Actually, the first model we tried, and I am still disappointed it didn’t work, was trying to generate letters to the editor that would spark debate. Looking back at other art publications like The Burlington Magazine, founded in 1902, there are people in there arguing with what Roger Fry has written and he is responding. I’m thinking, “God, that’s so amazing!” They actually had real arguments about things. I have to say, Artforum occasionally gets that going. The most letters to the editor I think we ever had was in the first issue, which is interesting because we received them before the publication came out. We asked people to write and tell us what we should do. Peter Wollen wrote and told us what we should do. Lane Relyea told us what we should do, as did Leslie Dick, who’s now joined the editorial board—she’s obviously known what we should do for a long time. I thought there should be some way of generating that, where the audience could come in and inhabit the publication by writing things. We did have an artist that we talked into doing this for a while. He wrote a number of letters but nobody ever responded to them.

EB: Dave Bailey. I wrote him back once.

BW: “Extra! Extra!”

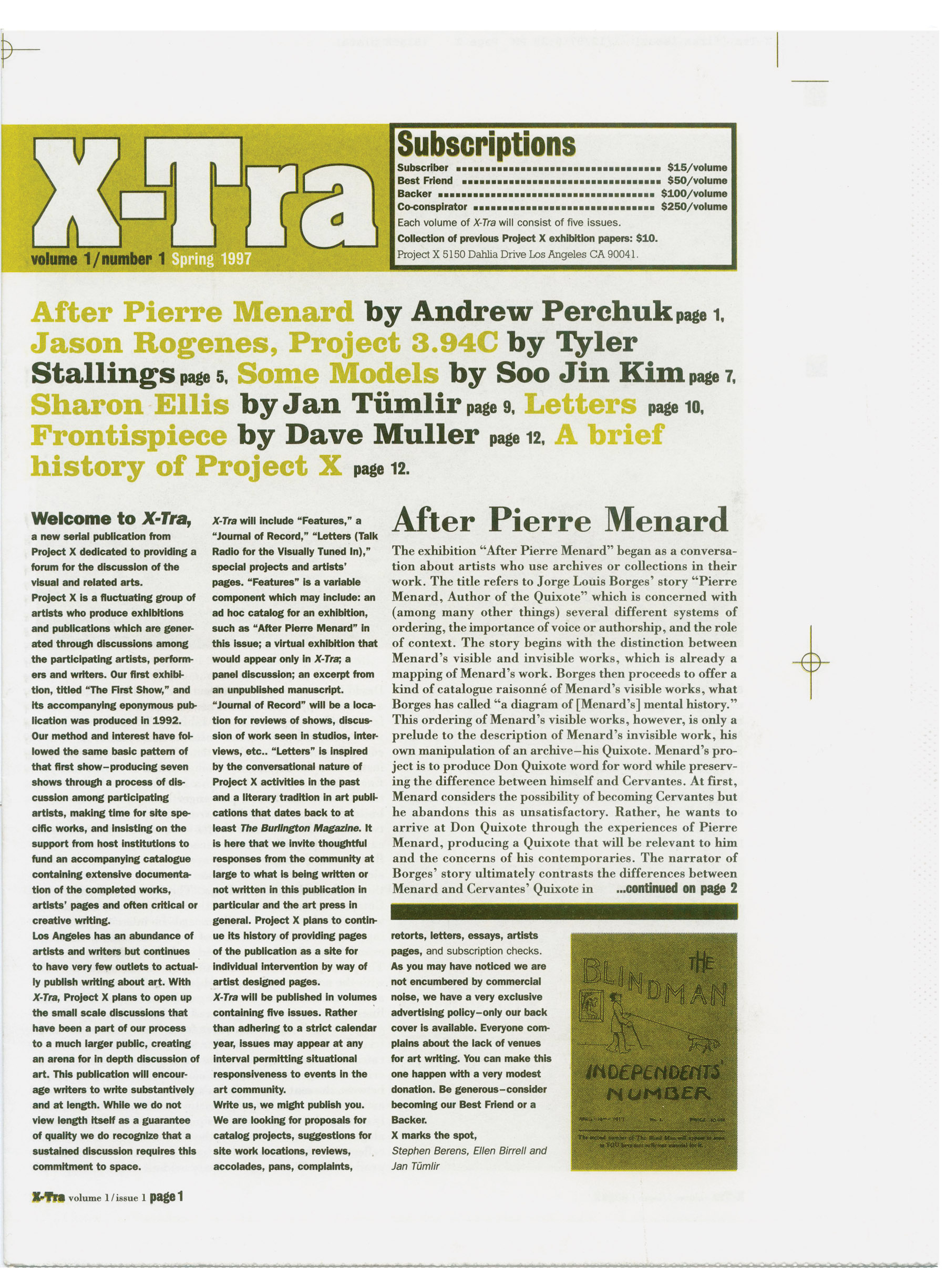

EB: Read all about it. You know, the reason why we called it X-TRA? As I recall, Stephen and I and Jan [Tumlir] and Jérôme [Saint-Loubert Bié] were all sitting around. One of the ideas that we were floating around for the magazine was that we would only put out an issue when we had a great piece of writing to run, that it would be an extra edition to a publication that didn’t otherwise exist.

SB: That was one idea. Another idea that never came to be was how we planned to fund the publication. We printed a lot of this first issue and said that we would only publish another issue when we got enough subscribers to pay for it. We had our publication party, and then a couple of months later we came up with a new business plan.

BW: As in, “I guess we’ll keep doing this, even though it didn’t go that way.”

SB: Originally our idea was to continue to do the exhibitions once or twice a year and print the magazine five times a year.

BW: So, sometimes the exhibition catalog approach would be folded into other content. But other times features and reviews would engage critically with exhibitions you hadn’t organized?

SB: That’s right: so we might have the catalog for a Project X exhibition wrapping around a section of reviews of other exhibitions. In the first issue of X-TRA, for example, there is a catalog essay for the exhibition Before Pierre Menard, written by Andrew Perchuk, which wraps around a series of reviews of other exhibitions happening at the time in Los Angeles.

X-TRA, volume 1, number 1, spring 1997.

BW: I was thinking about the artists’ projects and how they’ve changed throughout the life of X-TRA. Starting out as artist-run projects that included the exhibitions, how did that work once the focus was first and foremost the printed publication? It seems like the artist’s project wasn’t necessarily always there, but eventually became a standard feature of each issue.

EB: We have tried to continue the direct-to-print commissioning. Sometimes we ask people to invite people, but the core of the artists’ projects goes back, for me at least, to that early idea about site-specificity, both in terms of physical location but also in terms of print media. As an artist’s project for a magazine, it’s more self-consciously framed that way than many invitations for artists to show work in a printed context often are. It’s a pretty interesting library of stuff over the years that we’ve managed to do.

Micol Hebron started the 1 Image 1 Minute column, which was a different way that people got to contribute content to the magazine. What made me think of that in this context is that it strikes me as a way many artists, an extraordinary number of artists actually, have directly participated in providing content to the magazine. Sometimes the people who come to us as writers come from different formations than studio art backgrounds.

One thing that this fifteen-year mark represents is that core insight from those Project X days, which is if you give up some micro-managerial authority and instead share it collaboratively, you open yourself up to a much broader array of input and content. The editorial board still works on that model. Everybody on the editorial board sits down with an equal share of the discussion, an equal opportunity to generate content, either directly or through the agency of soliciting writings from someone else.

In our Saturday morning meetings, I often hear about stuff I don’t know about or that’s not necessarily in my area of particular interest. And often as I read a finished issue, I am interested in the way very different ideas about what’s important to talk about rub up against each other. The editorial board is an egalitarian and collaborative group. I think that makes us fundamentally different in terms of editorial structure from any other art magazine that I know of. That is one of the primary reasons why I think X-TRA has been able to sustain a lively vibrancy, flexibility, and nimbleness. That said, the population of the editorial board is constantly changing, so sometimes the interests around the table are more complementary than at other times. If you look through the history of the magazine, you’ll find times when there’s really diverse content. You’ll find other times when it’s really symbiotic.

SB: I think the magazine is really an outcome of the process. It’s a group of people that gets together and talks. Out of that discussion you end up with this [emphatically holding an issue], rather than an editorial process where you would sit down and say, “This is what’s going on; this major exhibition is happening in Europe; we have to have that covered, or this seems to be an upcoming trend.” I think a lot of magazines do that. There are magazines that set out to cover the market or cover who’s being shown or collected. I think those things are all interesting, but that is already being written about.

I also think there are publications that try to include art within the larger culture, writing about art, writing about fashion, and writing about music all in the same publication. X-TRA is in some ways, for better or for worse, really looking at what artists make and responding to that. Rather than looking at what museums are collecting of what artists make. I’m less interested in what museums collect and more interested in what artists make.

EB: Certainly, one of the things that makes me laugh every time I pick up yet another tome of Artforum is that, if you think about it as a site work, it clearly declares its investment in the market. Probably 95% of the physical content of any issue is ads about exhibitions. They place whatever critical editorial content they have within that envelope. That’s a business model. It’s a fact of living in American capitalism. It’s a fact of how collectively interested we are as a nation in where money goes and how money tracks or determines culture. Those are all really interesting things to think about, and Artforum does that in ways that are both aware and, I think, unaware, sort of blankly normative.

For a number of years now, I’ve been teaching a critical writing class for artists at CalArts, in part because of what working on X-TRA all these years has made me think about. I think that clearly we’re at a point after modernism and its various historical erosions, where we no longer think that the artist works with a single tool and doesn’t speak. The artist today doesn’t sit in an attic waiting for the lead paint fumes to kill her. She might pick up a musical instrument, might write, might paint, might perform. We understand the artist is somebody who occupies a creative periphery to mainstream culture that’s very fluid, using the most useful set of tools at hand to achieve a particular goal.

On the other side, the roles of critics and curators are no longer as fixed or separated as we have historically come to think of them. So, here’s my question: if we no longer limit the artist to working with her singular tool but rather think of her deploying any number of means, why aren’t artists the people to ask about what’s happening on the cultural edge, on the boundary of what’s not been seen, thought, or been thought about in quite that way before? It seems like the artist is one of the people who can tell us about what is going on on that frontier out there. By taking up the right to speak about what’s important in your field of practice and feeling confident doing that, we’re insisting that the conversation is about artwork that is grounded in a field of ideas, efforts, and speculations, some of which may be monetary, but not all. Writing about art is a way in which artists can build their own context for their works.

BW: Rather than being circumscribed.

EB: I could say you made something I thought was brilliant. Maybe five people saw it. If I can write a compelling argument for it and find a place for it, that thing has life. It goes back to my initial reason to participate in this, which is completing the responsibility to ephemeral but interesting artworks that might otherwise have no afterlife.

BW: Then, would you say the art historian or critic role we were talking about before is precisely on the same track, also trying to operate and be in a field of ideas because that’s ostensibly why they studied what they studied?

EB: Yes, but their methodology is very different from that of artists, which is why I find the conversations around the editorial board, which includes art historians, curators, critics and artists, very interesting. There’s a place in which, collectively, as an editorial group, we struggle to accommodate all sides of a conversation about art. I think this makes us editorially distinct, maybe not in every piece, but cumulatively throughout all the issues.

SB: I guess I see a slightly different history of writing about art. From around 1870 to the present, there are points in time, generally during points of drastic change, when it is the artists who are the main source of information. I look back and I think of Maurice Denis, whose writing on Cézanne was the best writing at the time. And when I go back to the 1960s, I look at Robert Morris, Donald Judd, and Joseph Kosuth.

EB: You are right, Stephen, and I didn’t mean to claim that artists speaking is brand new. In the first Project X paper, we wrote this mission statement: “Once again it has become apparent that artists need to take control of the processes by which their work is seen and understood.” It is still and again true.

SB: We’re actually reasserting the artist’s right to sit at the table and talk.

EB: Yes, and be a part of the big “durable culture” conversation.

BW: What are you both excited about with X-TRA now? Does it feel the same as it did five years ago in terms of your interest in how it functions and where it fits in the art world, or does it feel different?

EB: Yes. When we got the Warhol Foundation grant, for me personally, it was an endorsement of what we’d been trying to do, because sometimes it felt like what we were doing happened in an anechoic chamber where nothing came back to us—the problem of the letters again. To have this major foundation come and say, “This is deserving of support, and it needs to be helped to continue to exist,” was really powerful. I mark that as a move out of adolescence in a certain way. What has stabilized over this time is a clear sense of what the agenda for content is for the magazine. We have really long editorial lead times, so we cannot be informational in a dated material sense, we must aspire to a kind of deep speculative thinking about the artwork and about the world the work describes. That’s profoundly embodied in our new format as we go forward in volume 15 and 16. The new size and layout are hugely important to the quality of the reading experience. We have worked with many great designers who have listened closely to us, but our current form feels like the best fit we have collectively articulated so far.

The challenges that we’re facing at this point, of course, are the challenges that every small nonprofit in America is going through after the end of the big money drunk. We have a publication that is passionate about a very particular area of contemporary cultural production. Its base of support is understandably quite narrow, and we need to figure out some way to make it sustainable, at least until it is not needed or until someone does it better.

SB: In terms of a reading experience, I’m satisfied with the current magazine. The writing is good. We’re getting a broader range of people submitting materials to us. The artists’ projects continue to be really good. I think that this is a successful publication in that sense, but I also would like to see X-TRA, or the idea of X-TRA, reach a wider audience and produce more entry points.

EB: Among the things we’re thinking about is how our format works. The actual object we produce—the physical X-TRA—is good; but what other ways do people come to this? What other ways do people participate in this conversation about contemporary art? We’re going back to some of our Project X roots and really thinking about how and why we did events. We now do launches for every issue with some kind of original live programming, all of which is documented and archived. I am beginning to believe that we are broader programmers than we, or at least I, have recognized before.

SB: There are always personal things involved as well. When we did the first Project X exhibition, I had just turned 40. At that point, I thought, “Let’s just do this for now.” And then we’d ask ourselves every year, “Should we do this again? Should we continue or not continue?” There wasn’t the thought that somebody else would continue if we stopped. But that is part of the choice now. I’m not 40 anymore, and it’s not just a couple of us that are invested. There are a lot of people invested in what’s been produced.

To sustain X-TRA into the future we need to expand our support base and get new people involved. We probably had to be tightly focused to get the project off the ground. But now that is accomplished, we can afford to open up and reach out to new people. I hope people will realize that X-TRA, like the Project X exhibitions it grew out of, is an open system and we welcome their participation.

Ellen Birrell is an artist and lemon farmer. She lives in Santa Paula, California.

Stephen Berens is a Los Angeles artist and the co-founder of X-TRA.

Brica Wilcox is an artist and assistant managing editor of X-TRA.