“Beauty comes first. Victory is secondary. What matters is joy.”1

–Sócrates (Brazilian midfielder, 1979–86)

As the Liverpool manager Bill Shankly once famously remarked, football is not a matter of life and death, “it is much, much more important than that.” This maxim, probably football’s most frequently quoted, reflects the seriousness with which insiders take the sport. But football’s impact is broad as well as deep, and whether referred to as soccer, fútbol, or one of numerous other regional variations, more people around the world participate in and consume the game than any other collective cultural activity.2 Fans derive enormous emotional fulfillment from following their club and national teams—and perhaps, too, a disproportionate dissatisfaction at not winning often enough. The emotional release in either case, winning or losing, is intense.

Since football is the world’s game, and since, as I will argue in a moment, it involves a vital aesthetic component, it seems plausible to claim that football is also one of the world’s chief sources of aesthetic experience. It is not for nothing, after all, that football has come to be known as “the beautiful game.” Match commentary is often peppered with the language of aesthetics, appreciating a “beautiful” pass, a “lovely” header, a “sublime” goal. Likewise, commentators frequently express distaste for approaches to the game that seem crude or overly functional, that merely get the job done. This includes defensive play whose aim is to stifle the creativity of the opposition, as well as tactics such as the long-ball, where the ball is “hoofed” forward to the team’s striker, often from deep within a team’s own half, circumventing the need for more skillful, creative play in midfield. Even when this style of play succeeds, it is often disparaged in aesthetic terms as “winning ugly.”3 It is beneath the aesthetic standards implicit in the ideal form of the game, there is no artistry in it.

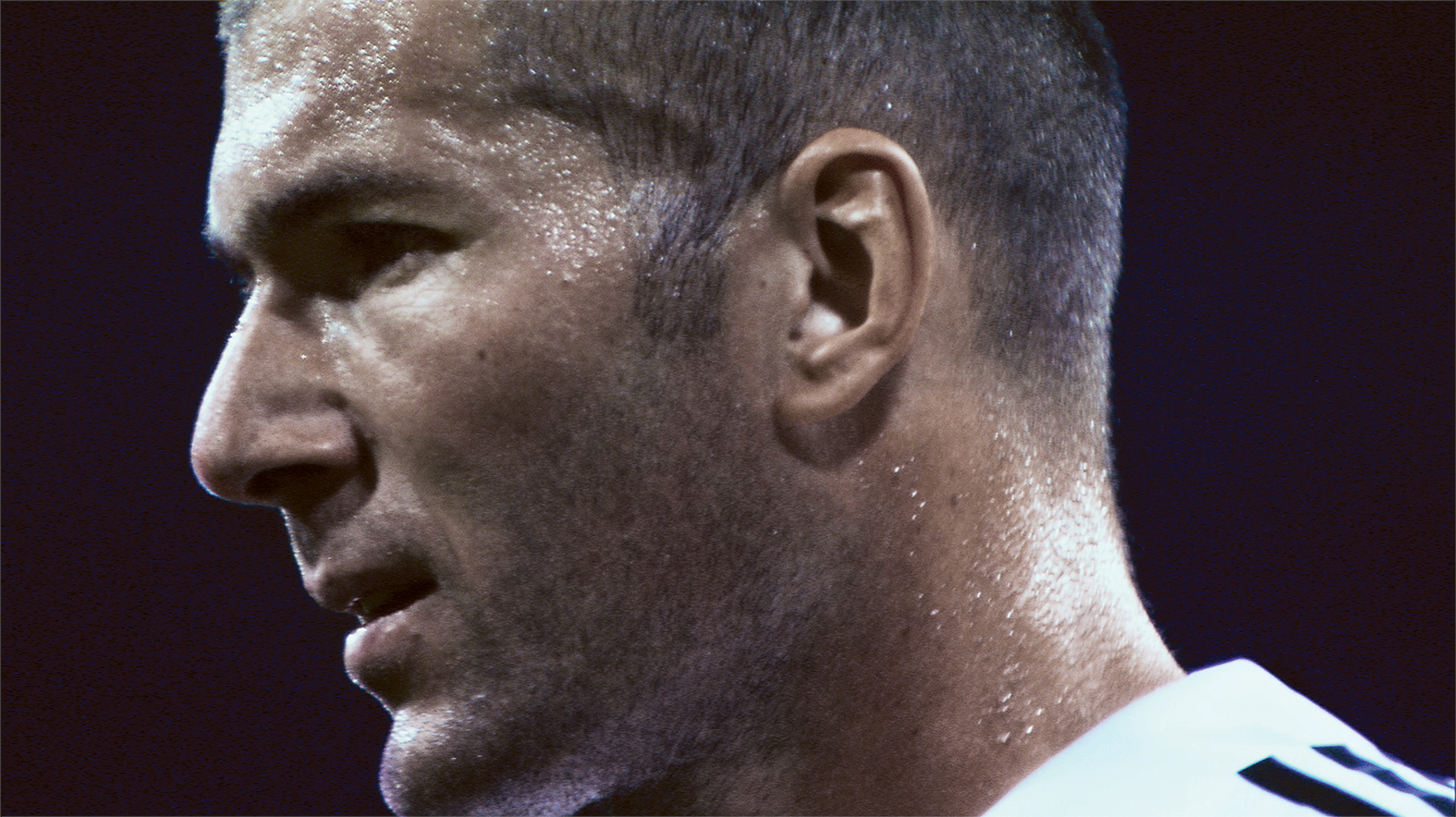

Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon, still from Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, 2006. Digital video, 91 mins. © Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon.

Yet in spite of the fact that players are sometimes identified as artists, football does not merit a place in Rosalind Krauss’s expanded field as an art form in its own right.4 (Shankly, meanwhile, would certainly have insisted that it was a lot more important than that.) Still, the game deserves to be taken seriously as an aesthetic practice. The recent exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Fútbol: The Beautiful Game, was predicated on this very assumption. Though my primary interest here is in the nature of football per se, rather than art about it, many of the works in the exhibition offer us a perspective on the aesthetic issues I wish to tackle. Additional historical perspectives will help to elucidate these issues further, especially the game’s origins in Victorian England and its subsequent development in South America. From an aesthetic standpoint it seems significant that modern football and modern art emerged at more or less the same moment—in mid-nineteenth-century England and France, respectively. Such a coincidence points to a common set of conditions giving rise to both phenomena. Football and modernism, both products of an industrial, urban age, can in part be understood as responses to the increasingly alienating environment that these conditions produced. Central to each was a unifying synthesis of the rational and the natural—a complex duality that has long been recognized as integral to artistic modernism.

The Aesthetic Dimension

In fact, for much of the history of football, concepts of beauty have gone hand in hand with the more functional outcome of scoring goals. The most efficient tactical solutions are frequently the most visually elegant as well. In this regard, Herbert Chapman, manager of Arsenal in the 1920s and ’30s, is of considerable interest. Chapman’s team was enormously successful during this period due to the innovative principles he implemented, which later prompted football historian Jonathan Wilson to identify Chapman as the game’s first modernist.5

The innovation for which Chapman will be best remembered is his development of a tactical formation called the “W-M,” so called because when seen from above its 3-2-2-3 arrangement of players forms those two letters. This radical formation was defensively stable (important at a time when teams were coming to terms with the uncertainty of a new off-side rule), as well as potent in attack.6“Breaking down old traditions,” a commentator at the time observed, Chapman “was the first manager who set out methodically to organise the winning of matches.”7 Wilson observes that analysts frequently identified the machine-like precision of Chapman’s Arsenal team, its functionalist approach, and the efficiency of its transitions from defense to attack. He draws an analogy with the modernist aesthetics of Le Corbusier: if, according to the great modernist architect, a house was a “machine for living in,” Chapman’s tactics were a machine for winning matches. The implication of this modernist principle, of course, is that functionality also brings beauty in its wake, and Chapman’s W-M certainly possessed a pleasing symmetry that complimented its tactical effectiveness.

The links between modern football and artistic modernism go deeper still, however, suggesting a common set of principles underlying both practices. It is an irresistible coincidence that the two phenomena were initiated at about the same moment: Modern art got going on May 15, 1863, when the doors of the Palais de l’Industrie in Paris opened on the Salon des Refusés, exhibiting, among other works, Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863). Manet’s work represented both an engagement with the contemporary environment and a frankness about the methods used to depict it that has continued ever since. Modern football began five months later in the Freemasons’ Tavern in Great Queen Street, London, with the creation of the Football Association, the English game’s governing body and the oldest such institution anywhere in the world. By codifying its laws, the F.A. laid the foundations for the sport as we know it today. Manet’s sporting counterpart, therefore, is Ebenezer Morley, a lawyer who had formed Barnes Football Club the previous year. On October 26, 1863, Morley convened a meeting of representatives from teams around London, who had hitherto played their own variations of the game, to resolve their disputes by “establishing a definite code of rules for the regulation of the game.”8

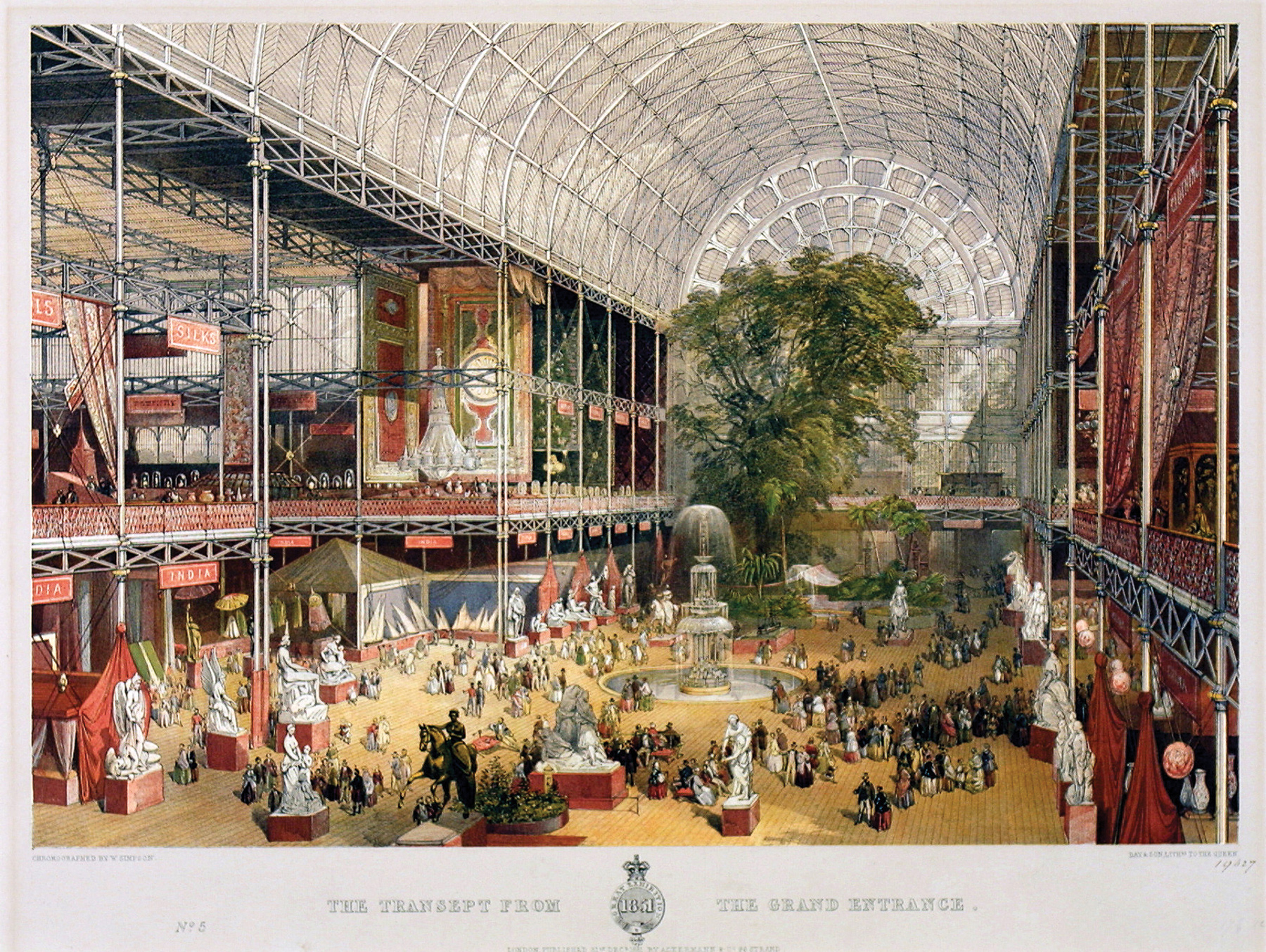

If we take this codification as central to the modern game, ushering in an era of order and regulation (as many other modern phenomena did—the railway, for example, had introduced a similar standardization in timekeeping), we might see its development as a symptom of an underlying Victorian condition. As such, a more productive touchstone by which to judge football as a modernist practice might be the Crystal Palace, a building that matches the Football Association’s impulse to order and clarify. It was its sense of order, in fact, that led Donald Preziosi to identify the Crystal Palace as “the first fully realized modernist institution.”9 Constructed in London in 1851 to house the Great Exhibition, this glass exhibition hall was the archetype for the Palais de l’Industrie; both buildings served as sites for rival exhibitions of industrial prowess in the 1850s. The Crystal Palace was by far the more radical, however, and was built with astonishing pragmatism. Erected entirely from standardized manufactured elements of glass and cast iron, forming modules from which the whole structure derived, it exemplified British utilitarian principles of functionality and technological improvement.10

Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Crystal Palace nave, Hyde Park, 1852. Albumen print from calotype (waxed paper) negative, 18 ½ × 22 ½ inches. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

After the Great Exhibition closed, the enormous building was moved from its original location in Hyde Park to suburban Sydenham, where it reopened in 1854 and remained until destroyed by a fire in 1936.11 In 1861, however, a group of workmen from the building formed a football team, naming it Crystal Palace after their place of work.12 Two years later Crystal Palace was one of the twelve clubs that took part in the famous meeting at the Freemason’s Tavern, which formed the Football Association. Though there is no causal connection between the two institutions, it is easy to see how the principles underlying the Crystal Palace—the impulse to order and classification—may also be perceived in the codification of the laws of football. These principles can in turn be seen as the very foundations of modern knowledge itself.

Their Football, or Ours?

But let’s step back for a moment. Just as art historians would argue that isolating the Salon des Refusés or the Crystal Palace as watershed moments oversimplifies the development of modernism, some historians of football would no doubt object to the valorization of Morley and the English F.A. above other significant trends and moments. Football-type games, they might say, have been played all over the world for millennia.

In his history of the game in South America, Soccer in Sun and Shadow, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano emphasizes just this historical and geographic diversity.13 He points out that the Chinese juggled balls with their feet five thousand years ago, while later the ancient Egyptians, Central Americans, Amazonians, Greeks, Romans, and Medieval Europeans all played similar games, which often incorporated ceremonial elements. These were rituals as much as pastimes and were carried out according to the demands of their local situation. This point is underlined very neatly by Brazilian artist Nelson Leirner’s Maracaña (2003), a sculpture included in LACMA’s Fútbol exhibition, consisting of a scale model of a football stadium populated with a multiplicity of action figures and statuettes from all kinds of religious and cultural origins. The players facing off against one another are, on one side, a team of Incredible Hulk miniatures, opposed on the other by a team of red Power Rangers. In the crowd, meanwhile, are serried ranks of Buddhas, Disney dwarfs, Roman centurions, and Virgin Marys, among countless others. The diverse mixture of institutions from which these figures derive speaks eloquently both to the complex and hybridized origins of the game, as well as its contemporary ubiquity.

Nelson Leirner, Maracaña, 2003. Installation view, Fútbol: The Beautiful Game, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2014. Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA.

In the late nineteenth century, the global spread of football—a classic piece of British cultural imperialism—sparked a complex phase in this process of hybridization, producing a multiplicity of forms of the game. Introduced to Uruguay by British traders, football was initially regarded by the locals as an eccentric national quirk. According to Eduardo Galeano, it was seen as “that crazy English game,” its characteristics “as typically British as Manchester cloth, railways, loans from Barings or the doctrine of free trade.”14 For this reason the first internationals between Uruguay and Argentina were actually put on by British expatriates living in Montevideo and Buenos Aires; the teams were clad for these occasions in kit literally imported from England. The language used during matches in South America was English too. The first rulebook available in the region stated that in the case of a “foul,” an apology would be accepted only “as long as his apology was sincere and was expressed in correct English.”15 This state of affairs would remain for many years, a symbol of the perceived British stewardship of the game.

In 1935, the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García was still referring to the game as alien to South American culture, its influence potentially deracinating and contaminating: “If we ask what this game contributes to our country,” he opined, “the answer is zero.”16 The essay in which he made this comment, “The School of the South,” was an emphatic statement of Uruguayan cultural autonomy in which the painter attempted to identify an authentic indigenous artistic tradition. Torres García grew up in Montevideo around the time football was first introduced there. At the age of 17, however, his family moved to Europe, where his artistic training occurred, taking him first to Barcelona and Paris and then back across the Atlantic for a time to New York. When he returned to Uruguay in 1934, Torres García was keen to make a break with the old world, to close the door and leave the European influence behind. He singled out football for particular disdain: “What has [it] got to do with us?” he asked.

In fact, Torrés García had failed to appreciate that during the time of his absence from Uruguay, the country had adopted the English game and radically transformed it.17 As Galeano explains, after football was taken up by the youth of Montevideo and practiced in cramped alleys, on beaches and in the fields, what emerged was a new form. Unlike the English, the players in Uruguay “chose to retain and possess the ball rather than kick it, as if their feet were hands braiding the leather.”18 This new, free flowing style—criollo fútbol—was a game for everyone, its inclusivity in marked contrast to its upper-class origins in England.19 This accessibility, as well as the way football insinuates itself into everyday life, is apparent in Oscar Murillo’s film Perreo (2013), another work exhibited at LACMA, which documents a simple pickup game of football played on a sectioned off stretch of alley in the artist’s native Colombia. The game is very much a part of the life of the street, with players coming and going, alternately intensely focused, then casually oblivious to it. The sounds of the city give further texture, whether the catcalls of spectators or the music pumping from a sound-system somewhere down the street. Everything is integrated into the syncopated rhythm of the game—players sometimes even stop to dance.

World Cup Final, 1930, Montevideo, Uruguay; Uruguay 4 versus Argentina 2. Members of the Uruguayan team celebrate after winning the Jules Rimet trophy by beating rivals Argentina in the first ever World Cup Final. Photo: Popperfoto/Getty Images.

The process of appropriation and enrichment the game’s export had produced was replicated in other South American countries as well, notably in Brazil, adding further cultural influences to the mix. “And thus was born the most beautiful soccer in the world,” concludes Galeano, “made of hip feints, undulations of the torso and legs in flight, all of which came from the capoeira, the warrior dance of black slaves, and from the joyful dances of the big-city slums.”20 Such a conclusion reinforces the idea that football is a distinctively modernist practice not least because it emphasizes that the game is a synthesis of new and old, the manufactured and the corporeal. Like the Crystal Palace, football’s origins were rational, the product of an industrial age of standardization. Even the way Englishmen originally played the game, mechanically passing the ball and running back and forth like a military exercise, seemed to express this quality.

Yet this is only one half of the story of modernity, as it is one half of the story of football. As the grandfather of modernism Charles Baudelaire pointed out, modernity has two parts, one half “the transient, the fleeting, the contingent, the other being the eternal, the immutable.”21 The Crystal Palace, likewise, possessed just this combination. Though clearly very modern in conception and construction, it also felt timelessly mythic: in places the glass structure was built over existing elm trees, creating the impression for some visitors of an enchanted forest. Lewis Carroll, for example, commented that it looked like “a sort of fairyland.”22 It was, in other words, a building that seemed to exist in harmony with nature in its oldest and most primeval form, not in opposition to it.

In its own way, criollo fútbol matched this synthesis of the industrial and the natural, a quality that could plausibly be seen as part of the natural order of things. It is also in line with the conception of modernism as a combination of classically “timeless” structures that emerged out of unyielding contemporary forms. The prime example of this, of course, was Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. This dynamic was at the center of criollo fútbol, which brought another dimension to the rule-bound English game, unfolding a sensuous, corporeal element that seemed, at least outwardly, deeply spontaneous and even natural.

A Discourse of the Body

Like the Crystal Palace, though, criollo fútbol was a carefully constructed edifice, the result, inevitably, of a regulated set of attitudes and practices. The joyous freedom in which its aesthetic consists also contains a paradoxical element of discipline and control, which Galeano points to by alluding to the style’s connection to the Brazilian martial art of capoeira.23 Seen from this angle, the various conventions, rules and organizational bodies of the game of football can be viewed as systems of control and regulation that have profound effects on the bodies of players.

Thus, football can be seen as a cultural practice whose specific characteristics are generated not only by its context, but particularly by attitudes toward the body within that context. In an essay from 1935 called “Techniques of the Body,” the French sociologist Marcel Mauss identified a range of “bodily techniques”—actions as seemingly natural as walking, as well as more obviously embedded cultural practices such as dancing or marching—onto which each culture impresses its own distinctive stamp.24 These all arise in particular ways in different cultures according to their own customs and attitudes, Mauss argued. The Maoris and the French dance in different ways, he observed, but so too do they swim differently. Applied to the game of football, then, we can distinguish the stolid, industrious play of Liverpool’s Steven Gerard (an Englishman), tirelessly running up and down the pitch in support of attack, then defense, and by contrast the fluid, dancelike skill of Barcelona’s Neymar (a Brazilian), as products of different cultural attitudes toward the body.

In his 1975 book, Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault described the way attitudes to the human body are created through the repetition and practice of particular tasks in a vast range of different contexts—from the schoolroom, the factory, the hospital, or the army barracks—pointing out that discipline and control are at the center of each of these structures.25 Foucault also emphasized these institutions’ similarity to their archetype—the prison—in the way they all regulate physical behavior through a matrix of rules. Correction and instruction—how and where to sit, play, and sleep—mold individuals’ attitudes to their own bodies and their relation to the bodies of others. It is easy to see how the football training ground, with its drills and fitness regimes, fits into this conception.

A group of footballers practice heading the ball in Germany, circa 1930s. Photo © FPG/iStock.

Foucault’s genealogical approach to history sought not only to discover the origins of particular systems of knowledge but also the ruptures and discontinuities within them, the moments when alternatives to the dominant paradigm show through. Correspondingly, the creativity of football is always struggling against the rules, the tactics, and the physical discipline needed to perform at the highest level.

The most dramatic rupturing of football’s paradigmatic code of conduct occurred during the final of the World Cup in 2006 when, ten minutes before the final whistle, with the game already in extra time, Zinedine Zidane, France’s totemic attacking midfielder, was sent off after head-butting an opponent, Marco Materazzi, in the chest. France ultimately lost the game, and the championship, in a penalty shootout. Had any other player committed a foul as violent and ill-timed as this, on the biggest stage of all (estimates suggest that 715 million people around the world watched the game live), the shock would have been considerable, but that it was Zidane, the finest player of his generation, intensified the feeling. Zidane had been the fulcrum of previous French campaigns, most notably their World Cup win in 1998, and was arguably the reason they had reached the final in 2006. At the age of 34, he had come out of international retirement to participate in the tournament and had received the Golden Ball, awarded to its best player. He was also known as a man of integrity, a man of honor. Why then would he throw all this away in front of hundreds of millions watching on television, for whom he was a hero and a role model? Why, to put it another way, after so many years of training and discipline, subjecting himself to the rules that made winning possible, would he choose to transgress them at that crucial instant?

As it transpired, a deeper code had imposed itself on Zidane’s conduct. While at the time the verbal exchange between them remained mysterious, and subject to conjecture, it is now known that Materazzi had insulted Zidane’s family, calling his sister a whore, and possibly also wishing an ugly death on the rest of his family. As Zidane said later, “I am a man above all,” and so, despite the high stakes, he released the violence barely held in check by the discipline of the rules of the game.26 At that moment, then, the demands of the code of football and all its modern underpinnings fell away, returning Zidane to an ethos of chivalric virtue, however misguided in the wider context. From his perspective, the Olympiostadion in Berlin became as a Medieval tiltyard, and Zidane, a knight-errant, his head a lance, defending his honor and his personal integrity. But though he won this skirmish, the wider battle was lost; France failed to win the Cup.

Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon, still from Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, 2006. Digital video, 91 mins. © Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon.

This moment is foreshadowed in a film by the artists Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon, entitled Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), the centerpiece of LACMA’s Fútbol exhibition. The film documents a game played in the Spanish Liga between Real Madrid and Villareal in April 2005, a year before Zidane was sent off during the World Cup final. The film follows Zidane exclusively for the duration of the game from the shifting viewpoint of seventeen cameras trained on him around the ground, making the spectator aware of the elegance and decisiveness of the player’s touch and his masterful awareness of space on the field of play.27 We are also aware of how much of the time he is not in possession of the ball, and his intense mental and physical concentration, his body poised for potential action, as if continually anticipating its next move. Yet the film culminates in another moment of violence, when Zidane is sent off during the final minutes of the game after a brawl with an opponent. Taken together, these incidents seem to suggest that Zidane’s creativity and his transgression of the rules of the game are somehow linked, that his capacity to see the possibilities of the game beyond that seen by his teammates also caused him to step outside the rules, just as the young players of Uruguay in the early twentieth century saw beyond the way the English habitually played the game to create its modern form. Johan Cruyff, another of the game’s most creative players, once commented that he could never be a referee because he didn’t know the rules well enough. “I always make my own rules,” he said.

Total Football and the Gesamtkunstwerk

If individual creativity sometimes involves breaking the rules, the experience of watching a football match is profoundly collective and unified. As such, the game shares something with the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk—Richard Wagner’s influential concept of the “total work of art,” a theatrical synthesis of music, literature, painting, sculpture, and architecture. In his recent book on the history of the idea, Matthew Wilson Smith identifies collectivity as its central characteristic. Inasmuch as it sought to immerse its audience in a communal experience, the Gesamtkunstwerk expressed what Smith describes as “a longing for unity amidst fragmentation, for collectivity amidst alienation.”28 It was, in other words, the quintessential modernist response to the crisis that industrial modernity provoked. In tracing the lineage of this idea (through the Bauhaus, Brecht, Riefenstahl, Disney, Warhol, and cyberspace), Smith also identifies the influence of the Crystal Palace on its emergence. Though not a fully fledged Gesamtkunstwerk, lacking the theatrical control of the form in its truest sense, Smith is nevertheless keen to point out the way the Crystal Palace presented a totalizing experience. Housing lush foliage alongside the products of manufacture and the mass of humanity who came to visit, the building created “a new unity wherein nature was commodified, commodity naturalized.”29

J. McNeven and William Simpson, The Transept from the Grand Entrance, Souvenir of the Great Exhibition, 1851. Color lithograph, 12 @/5 × 18 ½ inches. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Aviva stadium, Dublin, Ireland, built 2007–10. Photo © sasar/iStock.

Football has followed in this totalizing tradition. Sports stadiums are in many ways the equivalent of the Crystal Palace in the way they synthesize the elements of the commodity (the ubiquitous commercial advertising), the body (the players), and nature (the grass playing surface), making them available to a mass audience that watches in the stadium itself or on TV elsewhere. Many stadiums even resemble the Crystal Palace in form, especially those with retractable transparent roofs. Notable examples of this type are the Amsterdam Arena, home of the Dutch club Ajax (of which more in a moment), and the Aviva Stadium in Dublin, a structure whose transparent polycarbonate façade and roof match the functionalism of its nineteenth century forebear, maximizing daylight to the building interior, the pitch, and the surrounding neighborhood.

As in the stadium, so on the pitch: During the early 1970s, football developed an attacking style of play known as Total Football—its own form of the Gesamtkunstwerk. Pioneered by AFC Ajax, its tactical innovation consisted in getting rid of fixed positions for outfield players: roles instead were interchangeable, players switching position as necessity determined. This approach was extremely dynamic and proved very successful. Its architect was the Ajax manager, Rinus Michels, but its chief exponent on the field was the Dutch footballing icon Johan Cruyff. In his analysis of Dutch football, Brilliant Orange, David Winner recalls watching Ajax play for the first time on TV in the final of the European Cup of 1971. “They ran and passed the ball in strange and beguiling ways,” he remembers, “and flowed in exquisite, intricate, mesmerizing patterns around the pitch.”30Clearly, then, the way Ajax played, which consisted chiefly of this innovative conception of space, produced a style with an inescapable aesthetic dimension.

We get a further sense of the importance of the space of the football field as a dynamic environment in Andreas Gursky’s Amsterdam, EM Arena I (2000). This monumental photograph was taken at Ajax’s current home ground and shows a match that took place during the Euro 2000 competition between the host nation, Holland, and then World Champions, France. Gursky’s image is typically cool and detached, showing a large portion of the playing surface from a very high angle with the players spread across it. The ball is not visible, presumably having gone out of play on the left side of the field, but the players continue to orientate themselves toward it. One of the players, France’s Christophe Dugarry, has fallen to the ground with an injury. Around him the others reorganize themselves in anticipation of what will come next: a throw in, a free kick, the trainer coming onto the field? Neither we, nor they, know. By focusing on the field and excluding the spectators in the stands, Gursky’s picture allows us to think about what seems, on the face of it, the fairly simple proposition of a football match: twenty-two players moving about in a space about 120 yards long and 80 yards wide.31 But as we consider the almost infinite tactical permutations available, and the enormous variety of possibilities for movement the game presents, the intense and creative awareness of space that it demands, the game’s simplicity is revealed as a lie. Cruyff himself was all too aware of this. “Simple football is the most beautiful,” he famously commented, “but playing simple football is the hardest thing.” Cruyff’s attitude reinforces the impression gained from Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait: making simple but decisive moves requires players to maintain an optimal position in relation to other players at all times. This in turn calls for extraordinary focus on the space around them.

As if to emphasize the high level of spatial awareness football demands, Barry Hulshoff, who won the European Cup with Ajax in 1971, 1972, and 1973, later recalled the way in which the team’s play was underpinned with a conjectural, abstract approach to the dynamics of the game: “We discussed space all the time. Cruyff always talked about where people should run, where they should stand, when they should not be moving.… It was all about making space, coming into space. It is a kind of architecture on the field.”32Yet the interplay between these two realms—between theory and practice—is part of what makes football a complex social practice, and the more intimately intertwined they are, the more aesthetically meaningful they become. In this sense, innovative tactical formations are the manifestos of football.

And so we return finally to the idea of the collectivity of the Gesamtkunstwerk. Arguably, Total Football, with its integration of the dynamics of space, its on-field egalitarianism mixed with individual flair, and the beguiling aesthetic that resulted, has come closest to the radical agenda that the Gesamtkunstwerk proposes. As one Dutch journalist put it, “Cruyff was the first player who understood that he was an artist, and the first who was able and willing to collectivize the art of sport.”33Yet what might ultimately mark football as a quintessentially modernist practice is the absence at its center. As I mentioned at the outset, the pain of losing often outweighs the joy of winning. Even the most ecstatic win is fleeting, to be followed inevitably by the disappointment of subsequent failures. This is the melancholy heart of any modernist work, as Baudelaire knew all too well—the unsustainability of satisfaction in a world marked by alienation and loss. And yet fans cling to it and its vestiges of community once a week. Football remains, after all, more than a matter of life and death.

Jon Leaver is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of La Verne. His research focuses on nineteenth-century European art and criticism as well as contemporary art.