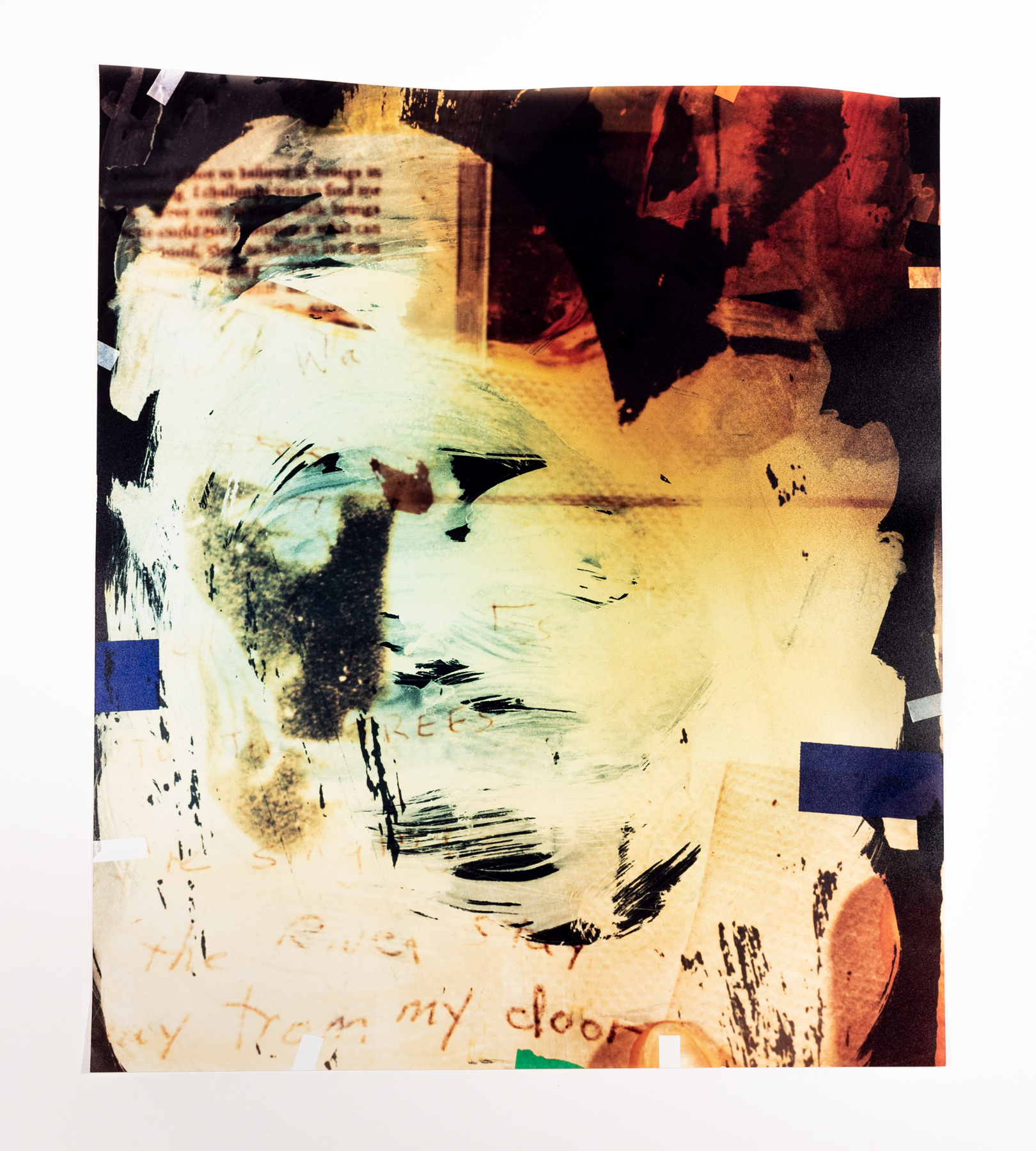

Carrie Schneider, Tender and Tenderized, 2021. Unique chromogenic photograph made in camera, approximately 25 × 20 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

KAJA SILVERMAN How does your new body of work relate to your previous work?

CARRIE SCHNEIDER I started creating these chromogenic monoprints in October 2020, and it is ongoing. It’s easiest for me to connect its lineage materially to the process-oriented work I’ve made since 2014, where I “shoot paper” in large format cameras, building up textures and obliterating images through multiple exposures. For this new body of work, I built a view camera with a special back that could accommodate 24-by-30-inch photographic paper cut from a large roll. I basically made an abstraction device. The theoretical connections to my previous work are harder for me to put a finger on. Ongoing threads I can identify are located more in the imagery I’m choosing, which might give insight into an interest in the history of art, specifically the way artists have pointed to their role in a social sphere, in performance and the body, and in holding ambivalence and the feminine.

SILVERMAN I assume that when you say “process-oriented” work, you are referring to Summer Drawings (2014–15), and that makes sense, as long as we limit the discussion to process. But the new work is in color, on a much grander scale, and feels very different to me affectively. If I were asked to relate them to an earlier series, it would probably be Burning House (2010–12), or perhaps Recession (2009).

SCHNEIDER I am astonished to hear you make these connections. Sometimes I have a block on previous bodies of work. I think there’s a usefulness to rejecting the past, at least temporarily, in order to move forward—but what you’re saying really resonates. Yes, there is a connection between Burning House and this new work in the use of what you, in our previous conversations, have called “ecstatic color,” but you’re also tapping into the theoretical and psychic underpinnings that allowed that work to take shape. Process was, of course, central to that work, too. The quietness of the final photographs and video makes the intense amount of labor less visible, but for me it’s important to the understanding of the work that I personally built and burned each of those shacks with my own hands, over years. While making Burning House, I often thought about Robert Smithson’s characterization of Marcel Duchamp’s reassembling of panes of broken glass as “a gesture against entropy.”1 Perhaps this ethos also guided my new work, as I grasped for meaning in a pandemic. Is this what you’re tapping into?

Carrie Schneider, Burning House (August, raining, early), 2010–12. Chromogenic print, 40 × 50 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

SILVERMAN Yes, but also this: When I look at the Summer Drawings, I feel as if I am once again a young girl lying in the backyard on a very warm day, with a slight breeze, half asleep, and watching the play of light and shadows cast by the movements of the trees. The affect in Burning House and the new work, on the other hand, has a very “late night” feel to it. The pile up of images that happens in the new work in a synchronic way also happens in Burning House in a diachronic way. Both feel destructive as well as creative, and slightly dangerous.

SCHNEIDER I love your read. For me, layering exposures is the closest I come to understanding synchronic time. As for Recession, your intuition is, again, spot on. The ambivalent ecstasy/exhaustion performed by a white woman under accelerationist late capitalism? What could better describe the new work, too, than me pressing myself against tempered glass?

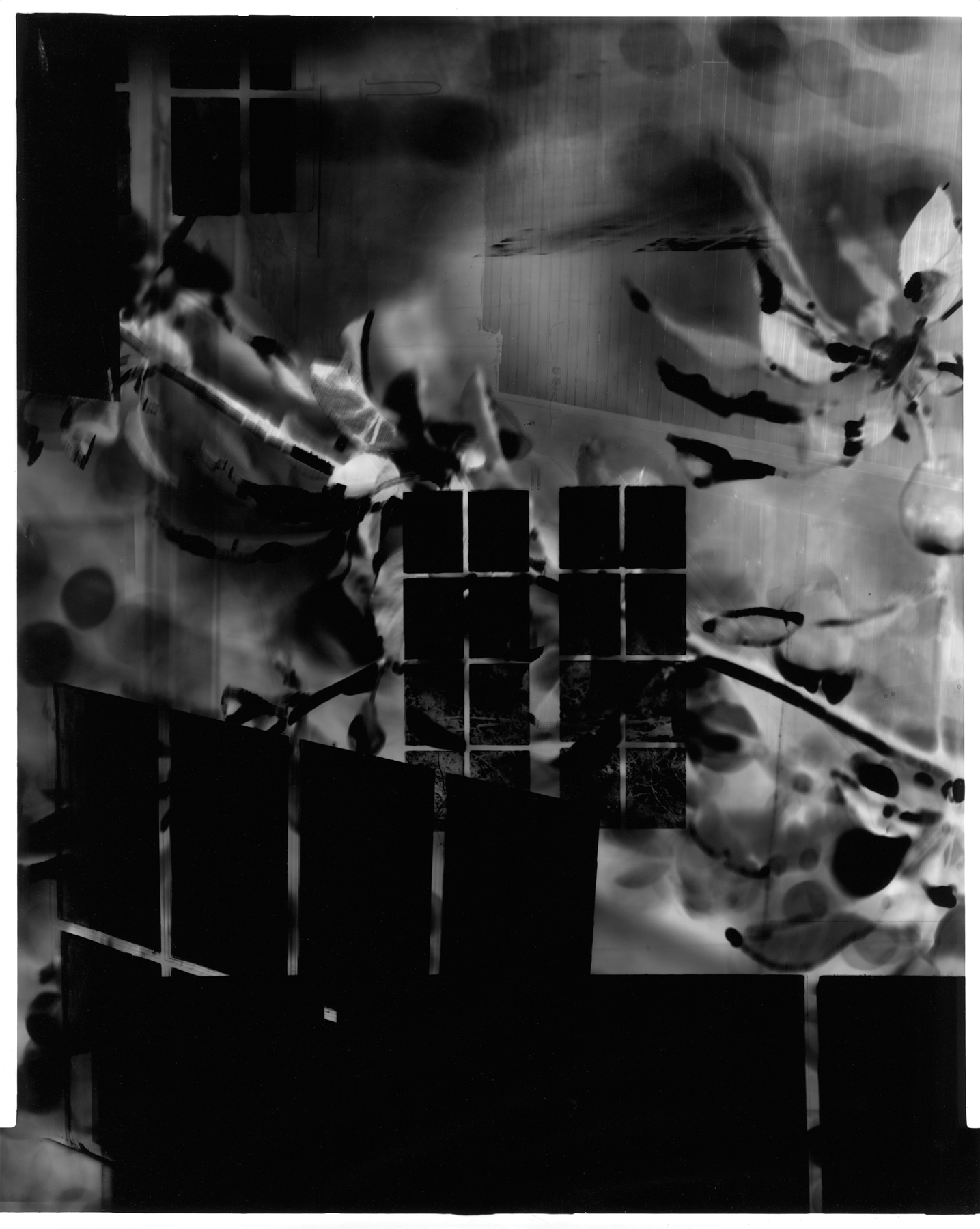

Carrie Schneider, Black Windows (Ox-Bow), 2014. Unique gelatin silver print made in camera, 10 × 8 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

SILVERMAN And, once again, it might be called the “2 a.m. affect.” As you have just suggested, through your reference to tempered glass, Recession can also be read as a proleptic allegory about our present relationship to the cell phone, and your use of the cell phone to produce these images. The white outline around each of the store windows has the shape of a cell phone, and the scratches on the surfaces of the windows analogize those on a phone screen. The windows are like those that I dream of lining up on a huge computer screen, so that I can compare the different versions of a document. They recede, but at an odd angle, and like the windows on a computer screen, they can be “recalled.” They don’t—in other words—vanish. The figure is “glued” to the store window, as many of us are to the computer screen. The half–formed images in the recent works beckon, seductively, like those that we glimpse out of the corner of our eyes while racing through a website or fast forwarding through a video. And as you say about the glass in the shop windows, there is nothing behind the glass . . . except digital “dust.”

But how does using images from a phone function for you, in this new body of work?

Carrie Schneider, Recession, 2009. Chromogenic print, 30 × 36 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

SCHNEIDER I mean, it’s no mistake that the apparatus is so seductive. What does surprise me is the physical sense of home that the phone produces. As much as we’ve been at home in past months, we’ve been spending time HERE [gesturing to phone]. The immediacy of the phone and its social function, particularly during the pandemic, are undeniable. I often think of a Guardian article about a recent anthropological study with the clickbait title, “Smartphone Is Now the Place Where We Live.”2

SILVERMAN Many people also go to bed with their cell phones. I sometimes reach for mine in the middle of the night—and find it under my pillow, although I don’t remember putting it there.

SCHNEIDER I will too. My awareness of its insidiousness can’t completely counteract the comfort that this device can provide. In practical terms, when I’m working in my studio at four in the morning, trying to expose a new image to light sensitive material before the sun rises, there is an ease and honesty with simply pulling up any image that comes to mind on my phone. The flatfooted ugliness of showing the phone, its lack of preciousness, appeals to me. Showing the apparatus also flattens the imagery, in a cultural sense (thinking of Michel Foucault via Giorgio Agamben). Every image that comes to me through my device is vernacular.

SILVERMAN Many of the photographs feature an image at the center of the works that derives from a different source and is important to you, such as Jeff Wall’s Stereo (1980). How would you describe these images? What kind of inner space is that?

SCHNEIDER I have been working pretty intuitively, and I’m hesitant to attach too much language to my decision-making process. However, I believe I’m choosing images that feel immediate but unsentimental. Among the images I’ve sourced are photographs from my own archive—older snapshots, or images I would likely not show as my own work, have now moved to the center. Same goes for images I’ve screengrabbed, from the news and from friends’ social media feeds. Taking screenshots is my form of note-taking: there’s a timestamp, a randomness, a collision of high and low, capitalist guilt and pleasure. It’s a private process that isn’t really personal either. I can best describe it via Lauren Berlant’s “intimate public sphere,” in that the affective ties of an attempted autobiography are, in fact, anxious and ambivalent.3 Also appearing are excerpts of art and artists that have been formative to my thinking about art and making: Wall, Sigmar Polke, Francisco Goya, Rosemarie Trockel, and Chantal Akerman all make appearances. I’m interested in where these artists’ practices overlap—for example how Wall sources Edouard Manet, Trockel sources Arnulf Rainer, and Polke sources Goya. The spirit of “fair game” is irresistible, in that it is at once an homage and a theft.

Carrie Schneider, Stereophile, 2020. Unique chromogenic photograph made in camera, approximately 25 × 20 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

SILVERMAN Titles have a very different status here than in your previous work. Where do they come from?

SCHNEIDER I write every day. First thing in the morning, I’ll write several pages, alone or alongside friends from At Louis Place.4 I collect titles from this ongoing stream of thinking, and sometimes they attach themselves to the images. My process for producing this new body of work has a similar stream-of-consciousness quality, and people who know the work and what I do have likened it to automatic writing. For me, the titles reveal something of this interior space and also position a solid point of contrast or conflict within what might otherwise be a largely abstract field. So, I’m not trying to lock down meaning, but I hope that providing some locatable specificity could produce a more expansive, open read.

SILVERMAN Your titles seem very biographically specific. They are clearly drawn from your life, but many of them also point in other directions, as well, and they feel “symbolic.”

SCHNEIDER Yes, for sure. For example, Hashface (he died first) (2021) is an abstracted wash through which you can make out fingers holding a phone showing a detail of a marble sarcophagus lid with two reclining figures. The male figure has a fully articulated face, with a lopped off nose. The face of the woman, who is turning toward him, adoringly, resembles common American diner hash. Cubed and piled—and as violent and everyday as misogyny. Hashface was the first term that came to mind, and it rings like hashtag. It’s tacky, it stuck. Visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the middle of winter in the pandemic with my close friend Dana DeGiulio, we lamented the pillaging that brought these incredible objects in front of us. We stared at the sarcophagus together, for a long time. Masked and distanced, I’ll never forget it. After some time, Dana shrugged and turned, saying over her shoulder, “He died first.”

To make this final photograph, I exposed a painting I had made in my studio on top of a second exposure of another image I had initially considered a double mistake. It was overexposed and completely flooded red with daylight. This resulting image, made by rephotographing the previous, converts the original back to a positive, turning the flood of red and black into a wash of cyan and white.

Carrie Schneider, Hashface (he died first), 2021. Unique chromogenic photograph made in camera, approximately 25 × 20 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Chart, New York, and Candice Madey, New York.

SILVERMAN Can you talk about Drive Forever (2021)?

SCHNEIDER Here I’m incorporating a motif Sigmar Polke used many times, the old magic trick of scissors floating above a glass of water. I tore Polke’s photo out of a dilapidated book. I think Polke often raises questions about the human desire to be mystified and how that continues to captivate us. Suspension of disbelief is made visible here—a visual pun. That the scissors resemble a phallus and the glass is a wet, receiving vessel isn’t lost on us, either. And that’s my thumb.

SILVERMAN It looks like a little chimpanzee, poking its head out.

SCHNEIDER Ha, yes, it’s my hand holding up a phone just outside of the picture plane. I have a particularly artful manicure given to me by my six year old, Hank, during one of the many snowstorms that inundated upstate New York earlier this year. Here is an image I borrowed, a bokeh of head- and taillights, shot through a windshield at night. For the title, I’m paraphrasing the 1999 Smog (Bill Callahan) song “I Could Drive Forever,” which is, in short, about leaving town and not regretting it. This could seem like a very romantic work, but I was thinking about the death drive.

My dear friend, painter Molly Zuckerman-Hartung—who first introduced me to your work, actually—said my new photographs were more thinking than being. Maybe this is an attempt, again, and perhaps not even a successful one, to draw a distinction between photography and painting.

Carrie Schneider, Future Shock, 2021. Unique chromogenic photograph made in camera, approximately 25 × 20 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

SILVERMAN What about Future Shock (2021)? The phrase reverses the temporality of shock, at least as Sigmund Freud talks about it in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). But perhaps you were thinking of Walter Benjamin’s account of shock, rather than Freud’s, or Andy Warhol’s Disaster series (1963), or something else altogether.

SCHNEIDER I love the phrase “Future Shock,” but I can’t take credit. I borrowed it from Curtis Mayfield (“Future Shock,” 1973). I think the title functions in the ways you mention, and I was attracted to its internal contradiction, but maybe on a more literal register. Here, I source Francisco Goya’s Las Viejas (Old women, 1810–12),5 which I pulled up on my phone from Getty Images. In it, two old women are sitting, bejeweled and in ball gowns, reading the gossip rag Que tal? and gazing into a compact hand mirror. Father Time, also graying but powerful and six-packed, hovers above them, winged and holding a broom. He’s a silver fox. Again, the common misogyny—aging women are such easy targets. For Future Shock, I zero in on one woman’s face, which reveals the skull beneath her thin skin. To make the image, I exposed second- and third-generation reproductions of the original, so this work is simultaneously a third and fourth generation, a mirroring and a mirror. Las Viejas was a “personal” work of Goya’s, in that there was no commissioning patron. This painting was also a favorite of Sigmar Polke’s, and it is difficult for me to see this painting now without seeing it through his eyes. As was usual for him, he seized on this image and reprised it over and over—in painting, lithography, photocopy, photography—until he exhausted it.

SILVERMAN Richard Avedon once said that every face is a state of emergency. As I was listening to you, I suddenly realized that every female face is a future shock. The face that will cause that shock is already present, just below the epidermis. I once saw a video clip in which a fashion photographer talked about a recent photograph that he had made of Catherine Deneuve. “That didn’t used to be there,” he said censoriously, pointing at a tiny crow’s foot at the corner of one eye. I sat motionless for about five minutes afterward, too stunned to move. And then I understood why Deneuve’s beauty has always filled me with such anxiety. Her face is so flawless that there is no room for “error.” All that it would take to get the gravediggers working is a smudge of lipstick. Faces play a very important role in this new work—in Hashface, Future Shock, and this one, francahiga (pussyfoot) (2020). But there is also a strong countermovement—a drive to erase or “deface” these faces.

SCHNEIDER The photograph francahiga is a third-generation reproduction of a screen grab of Dana DeGiulio’s social media feed. She placed her foot on top of H. W. Jansen’s Introduction to Art History textbook and snapped a photo of it. The book cover features Leonardo da Vinci’s Ginevra de’ Benci (1474–78), the only painted portrait attributed to da Vinci in a public collection in the United States.6 I know this painting well. As a teenager, I reproduced this image in graphite for a sophomore art assignment, also from a reproduction in a textbook. It took me two weeks. My friend Sara Corda, who is married to painter Lui Shtini, helped title this work. Francahiga is hyper-specific Sardinian slang for the term pussyfoot or pussypaw. The title would be raw and hilarious to a few hundred people. During the pandemic, Sara and Lui brought me a manuhiga (fig hand or pussy hand) amulet from Sardinia, where they live. It’s a traditional miniature carving of a fisted hand with the thumb between the index and middle finger, to be worn on a necklace. Like the evil eye, it is simultaneously a symbol of protection and a curse to those who violate it. The amulet’s red coral is the exact color of this photograph, which occurred due to uncontrolled light bleed.

Carrie Schneider, Empty Mind Shit, 2021. Unique chromogenic photograph made in camera, approximately 25 × 20 in. © Carrie Schneider. Courtesy of Candice Madey, New York.

SILVERMAN Empty Mind Shit (2021), now this is a very visceral account of defacement.

SCHNEIDER Defacing can be an additive or a reductive process, which maybe relates to using images as material—I’m handling images as physical objects. Making this new work, I discovered early on that cannibalizing my mistakes—by rephotographing, enlarging, flipping, and reversing the previous images— allowed for many iterations through which the image begins to break down. We see residue of the reproduction process. Where repetition of an image or word or gesture can lead to a sense of absurdity or stimulation through which new meaning emerges, repeating and magnifying an image produces abstraction, and the meaning splays. I’m thinking about conversations I’ve had with choreographer Kyle Abraham about our shared interest in repetition, both in our own work and in Andy Warhol’s work. I’m thinking about repetition as a comedic device, in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow Up (1966), and Hito Steyerl’s essay, “In Defense of the Poor Image” (2009). Steyerl says that the poor image is uncertain and “tends towards abstraction: it is a visual idea in its very becoming.”7 Does my relocating digital images into analog in this anxiety-filled moment indicate that a seed-library impulse is fueling my making? Like everyone else, I read Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993) during the pandemic, just as I started making this new body of work. By producing a fourth-, fifth-generation image, maybe I’m searching for a future in the finite cache of materials at my immediate disposal.

Kaja Silverman is the Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Professor Emerita of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of nine critically acclaimed books on topics ranging from the female voice in cinema to the life and work of artistic visionary James Coleman. Earlier in her career, she taught at the University of Rochester, Brown University, Simon Fraser University, Trinity College, Yale University, and University of California, Berkeley. During this period, she wrote Speaking About Godard (1998) with Harun Farocki, with whom she also taught four seminars at Berkeley. She is currently working on a trilogy about photography. The first volume, The Miracle of Analogy, appeared in 2015. The second, which includes a discussion of Las Bedidas (2007), one of the most important of Schneider’s works, will appear in 2022, under the title The Three-Personed Picture. Silverman is based in Philadelphia.

Carrie Schneider has presented her photographs and videos at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki; Galería Alberto Sendros, Buenos Aires; santralistanbul, Istanbul; Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen; Pérez Art Museum, Miami; The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; The Art Institute of Chicago; and The Kitchen, New York. Her work has been reviewed in The New York Times, Artforum, VICE, Modern Painters, and The New Yorker. Schneider is based in Brooklyn and Hudson, New York.