Recent shows in Los Angeles of work by Carey Young, Sharon Hayes, and Paul Chan offer three divergent visions of the contemporary public sphere. Each artist carefully carves out a relationship to “the people,” carefully playing on the line between cynicism and sincerity, illustrating views of the public and the possibilities of public speech. Young, Hayes, and Chan move beyond the prevalent ironic diagnoses of our failing political arena and towards something that might resemble faith.

Irony is an admittedly clichéd subject, but the English seem to understand it better than we do. I saved an article from The Guardian that has a rather lucid description of contemporary irony. The following excerpt on self-referentiality resonates, even if it makes the tired claim that postmodernism’s “core implication” is that “art is used up”:

Our age has not so much redefined irony, as focused on just one of its aspects. Irony has been manipulated to echo postmodernism. The postmodern, in art, architecture, literature, film, all that, is exclusively self-referential—its core implication is that art is used up, so it constantly recycles and quotes itself. Its entirely self-conscious stance precludes sincerity, sentiment, emoting of any kind, and thus has to rule out the existence of ultimate truth or moral certainty. Irony, in this context, is not there to lance a boil of duplicity, but rather to undermine sincerity altogether, to beggar the mere possibility of a meaningful moral position. In this sense it is, indeed, indivisible from cynicism.1

This is not the kind of irony that makes us marvel at the world, like, say, Beethoven’s loss of hearing. This is the kind of irony that preempts a moral position, and it is really bad for anyone desiring any kind of beginning or transformation—it’s bad for art, bad for politics, and depends on the assumption of a Habermasian bourgeois public sphere where felicitous or adversarial exchange is not even a possibility.

It was said by many pundits that 9/11 would put an end to irony.2 While irony certainly won’t vanish as a tool of critique, there does seem to be renewed interest in something more than the type of critique that irony affords. In the onslaught of horrendous policy decisions following 9/11, some artists are positing a different relationship to the public, one that suggests a reclamation of sincerity and establishes a possibility or imperative for a public sphere. Recent work by Mary Kelly and Andrea Bowers fits into this category. Kelly’s Circa 1968 and Bowers’ series Nonviolent Disobedience Training both look back at moments of protest and politicization that were dependent on an active public. Instead of situating the work in simple nostalgia, they re-present moments that might provide models or nodes for younger generations. Young, Hayes, and Chan are among a younger crop of artists looking at their own political climate. They’re self-consciously moving away from cynicism and irony and turning towards sincerity and faith, aiming to consider the resuscitation of a public or identifiable group in the present.

The last 35 years have seen the major institutions (political, financial, and cultural) thoroughly taken up by contemporary art; all have proven their ability to speedily absorb and neutralize ironic (as well as impassioned) art-attacks. Think of Hans Haacke and Fred Wilson, or more recent work by Christian Jankowski and Sam Durant. The possibilities for institutional critique have radically diminished over the past 30 years, but if we were to accept that in this post-postmodern period art has no effect on culture or politics, then art would have no audience- except itself. Maybe that is why the central question—How can an artist say something meaningful?—is by necessity totally self-reflexive, and the audience itself is often the subject of these works reconsidering public exchange. But, the inherent self-reflexivity in turning to the audience or participant as subject is something of a trap, since self-reflexivity is currently so closely tied to irony. How can one be self-reflexive without falling in to the quagmires of solipsism, narcissism, and didacticism? How does one actually say something, extend one’s hand, or propose an exchange between viewer and artist that is not equal in substance to a shared smirk or a bowl of Jello? There are many artists who are working around these issues with varying degrees of success; many are discussed in Grant Kester’s recent book Conversation Pieces.3 But few artists directly address the difficulty of finding a place from which to speak or deal with public exchange in a more standard gallery setting.

English artist Carey Young deals specifically with the delivery of speech, using well-worn modes of addressing the “public” in Everything You’ve Heard is Wrong.4 The 7-minute video from 1999 was included in the recent Champion Fine Art show curated by Walead Beshty.5 In the video, Young delivers a speech at Speaker’s Square, a historic Hyde Park site of public speaking. Once a center of debate for the likes of Marx and Lenin, it is now frequented by religious fundamentalists and tourists.

Young, having brought her own soapbox (a shiny, silver step ladder), steps up to speak. At first she is shaky and uncertain, wearing a rather large silvery suit (the artist calls it a “smart business suit” in her project description), repeating her desire to teach the ladies and gentlemen “presentation skills.” Eventually she starts rolling and, as a handful of onlookers gather around her, she begins her speech on “Public Speaking” at Speaker’s Square. She offers to provide the skills to enable anyone and everyone to climb up on the box and deliver their views confidently and effectively. And she doesn’t fail to mention that these skills are at least as useful in a corporate context. Young often utilizes corporate jargon in her work, applying business stratagems in unexpected situations.

In another piece on view at Champion Fine Art titled Incubator (2001), Young arranges for a Xerox venture capital specialist to work with the directors of the Anthony Wilkinson Gallery in London. The result of their meetings is a plan to get 10 new collectors a week. And while Incubator definitely rings of irony, Everything You’ve Heard is Wrong has a more nuanced quality. It is not because Young is “sincerely” offering free lessons to the public. The content of the lecture is kind of smirk-inducing; a bell goes off on the side of the disingenuous. The main ringer is her first bullet point: “Be aware of your audience.” Young’s audience is a random conglomerate of tourists, religious followers, and people on the way to somewhere else, and the corporate ploy of audience awareness is another one of her “misplaced” marketing strategies. The second point is almost as bad: “Have a message.” The self- conscious, meta-ness of her own message, highlighted by a religious speaker flanked by at least a hundred people in the background, does not, at first, point to a different kind of dialogue.

But why is it that Young’s performance tends towards the ironic? Perhaps it is because Young, “the artist,” is (so very literally) attempting to step into the speaking position. There is something in the re-play of the inherent vulnerability in the artist’s attempt to speak that conjures the yoke of the last 30 years of conceptual performance and video art. This restaging of the inadequacy of the artist, the “futility” in these “feeble” attempts to speak in the face of the powers of the institution feels like a well-worn strategy.

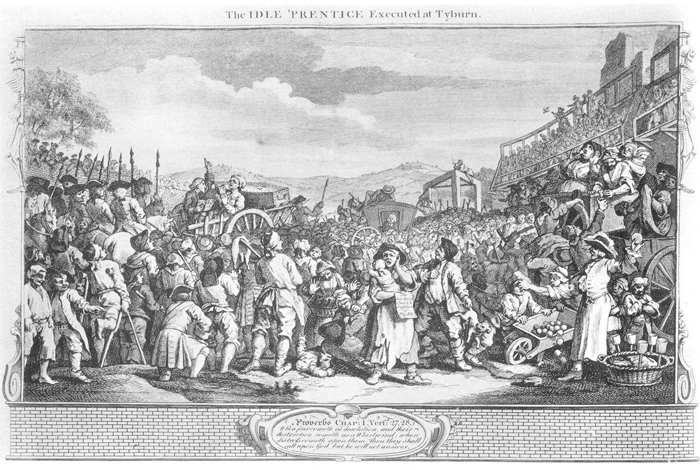

Interestingly, Speaker’s Square is very close to the former locale of Tyburn’s Tree, a major venue for public hanging in England. For hundreds of years, hanging days, like public holidays, would bring as many as 50,000 onlookers to the area of the square. It seems that this duplicitous history could have been called upon to render more depth in Young’s work. Young seems to leave the notion of the public unchallenged, allowing the people gathering around her to remain anonymous and unaffected. The humor (or irony) in her delivery of these “presentations skills” is dependent on a strict relationship between the artist and the other—a barrier between the two.

However, if Young is critiquing an approach to “public speaking” that is reliant on marketing strategies and designed for the effective delivery of pre-conceived messages, then the “failure” of her attempt, as recognized by both her outdoor audience and her gallery audience, has some gravity. Perhaps we as artists no longer have the tools to address a public or to be members of a public. But, if Young’s speech at Speaker’s Square is not successful in fostering some kind of meaningful relationship between herself and her audience, it does illuminate the lack of a critical public and the emergence of a manipulated one.

Sharon Hayes’ multi-channel, 37-minute video installation After Before directly addresses direct address, and contemplates problems of collecting, naming, and representing public opinion, whether it be critical or manipulated.6 Curated by Juli Carson, the “still in-process” installation was on view at Room Gallery at the University Art Gallery at UC Irvine.7 In her project essay published in the brochure, Hayes’ considers Ferdinand de Saussure’s diagram of the speech circuit, of “two people chained to each other by speech.” Hayes questions the way speech works—the way in which it is delivered and received — especially within the arena of politics and in relation to the kind of exchange inherent to the interview.

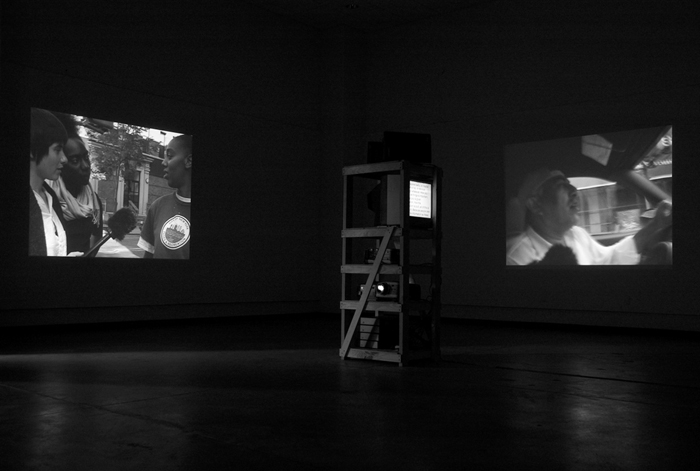

After Before is primarily composed of three large projections aimed at three of the gallery’s four walls. Two adjacent projections follow a pair of young women walking around New York City with a microphone—a typical documentary set-up—in the months before the nefarious election of 2004. The third projection shows a series of conversations between the two girls at a park table. A single audio track rotates between the three video projections, shifting the viewer’s gaze each time it switches.

The girls’ assignment is to conduct interviews with people on the street in order to find out how to speak to “The American Public,” and they seem to find a great number people, especially at this politically charged time, who are willing to stop for a moment and speak to them. The respondents stumble through answers to the girls’ awkwardly delivered questions: “How can I get a public opinion?” “What does it mean to be an American?” “How big is your TV?” What is the first political image you remember?” “What are you waiting for?” Throughout, the questions lead us to consider the “public,” its formation, and its representation in polls or on the television news. The girls constantly draw attention back to their own roles, glancing with uncertainty at the camera, seeking affirmation from the cameraperson and the viewer. Veracity is thrown into question through this constant reference to the scene’s construction, and this questioning was wholly intentional on the part of the artist. Hayes’ stated influences, Rouch and Morin’s Chronique d’un été and Chris Marker’s Le Joli Mai, address the same kind of problematic. Hayes wants to move beyond problems of representing a “typical” New Yorker or a truthful sample. In fact, the interviews in After Before seem to have been edited in order to enforce stereotypes, rather than feign objectivity. (In one sequence, a 40-ish woman in a business suit with white sneakers and a fluffy Standard poodle declares she knows that her candidate will win. One of the girls asks who her candidate is and she replies, “Bush.” The girl’s comment: “I didn’t even know there were Bush supporters.”) Hayes shifts the focus from documentary questions of truth to the limits of representation.

The third projection presents the girls’ own questions to each other. They sit at a park bench, facing one another, as in Saussure’s diagram, speaking of their positions in relation to the “interview.” On this projection, the sound is not quite synched, and the monologues delivered seem scripted or rehearsed. One of the girls says she is studying to be a psychoanalyst and considers the term “interview” in relation to her future profession. She concludes that the “interview” can be political, psychoanalytic, or market-driven, acknowledging that the interviewer must be trained to get the answers she wants and again highlighting this relationship between the critical and manipulative.

Hayes operates by undermining any superiority complex in the viewer by relying on an affect she calls the “quasi-fictional,” generating uncertainty about the motives of “truth-seeking” or interviewing. The naiveté or unprofessionalism of the interviewers and their charming, blank-slate demeanor, also prevents thinking in terms of a more official poll or typical sample. But at times, the “quasi-fictional” matures to the fully fictional, and the girls’ act of interviewing reads like an acting exercise. In these moments, the sincerity of the gesture, their thinking about speech and exchange that underlies the project, is threatened.

There is one more central element to the installation—the videos’ projection source. Instead of the typical ceiling or floor mount, the three projectors sit on a stocky, untreated wood scaffold in the center of the gallery. The structure, suggestive of a “man behind a curtain,” also holds a small monitor. The video on this monitor scrolls through transcriptions of the projected interviews but it is not quite synched to the audio track. The black text on white screen, constantly running, is generously sprinkled with typos and mistakes that may or may not be intentional. Strangely, it also reads like a teleprompter, generating the interviews. This “beforeness” points back to the highly edited tapes and the constructed journey of the interviewers. Here, we are brought back to the title: After Before.

Concurrently on view in a project space at the Hammer Museum is New York artist Paul Chan’s much celebrated My birds . . . trash . . . the future. 8 This large, two-channel video installation, also presented in 2005 at Greene Naftali in New York and in PS1’s Greater New York 2005, might seem to be more about silence than speech. But, like Hayes and Young’s videos, it also has a pointedness that approaches meaning or morality in relation to a public and the absence of a public voice or opinion in the current political climate. Chan creates a suffocating reality by way of an animated apocalypse, a sparse digital landscape inhabited by a rotating cast of characters. Its title suggests reading the work as a cautionary tale—as in, this will be the future if the current status quo is maintained.

In the center of the landscape is a large, stunted tree, most often serving as a roosting place to the various types of birds or a backdrop to the digital detritus blowing in the wind. At one point, this tree holds a number of bodies, swinging from nooses. The figures twist in the wind, their arms rising up. In other scenes, soldiers (or perhaps insurgents) move in and out of vans and pickups, guns waving. The soundtrack, in stark opposition to the voices of hopeful women in Hayes and Young’s videos, is a cacophony of car alarms, cell phone tones and birds. The silence of the human voice is so totalizing that the viewer is propelled by her repulsion to it to break that silence. In Chan’s political landscape, no one speaks, Tyburn’s tree grows over Speaker’s Corner and the public is constituted by a gaggle of Aristophanean Birds, Biggie Smalls, suicide bombers, and Pier Paulo Pasolini.

Like the three ghosts that visit Scrooge on Christmas Eve, Young, Hayes, and Chan might be seen as the Spirits of the public’s past, present, and future. If only they could have the same transformative affects upon art’s dependence on irony as Scrooge’s Spirits did on his stinginess…

Shana Lutker is an artist and the office manager at X-TRA. Her website, http://www. cataloguecatalogue.com, is still “in process.”