Before starting work go thru [sic] all the former material / many things of vital importance have been lost sight of…

-Charles Burchfield

This fall the UCLA Hammer Museum of Art features an exhibition of the work of Charles Burchfield (1893-1967), a well-known but peripheral figure to the histories of Modernism, curated by Robert Gober, an artist whose austere and unnerving sculpture and installations made him a central figure in an international art world at the turn of the millennium. The pairing of the two for Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield offers a chance to think about the diverse engagements of artists, to examine the machinations of history, and to reconsider what we might explore as contemporary.

In 1917, Burchfield’s self-proclaimed “golden year,” crucial themes of his practice emerged in his early works, many of which are linked to the natural environment. Several watercolor paintings from this time concentrate on sound: The Song of the Katydids on an August Morning (1917), Churchbells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night (1917), and Insect Chorus (1917). The synesthetic task of depicting such events seems to resonate across this period for the artist. Each subject is an immediate reminder of the complexity of looking at our world, or how one sensation becomes linked to another, experience as accumulation.

Charles Burchfield, The Insect Chorus, 1917. Opaque and transparent watercolor with ink, graphite, and crayon on off-white paper, 20 x 157⁄8 in. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art, Utica, New York. Edward W. Root bequest, 1957.

Burchfield’s process was also one of accumulation: images, journal entries, notes, drawings, sketches, doodles, and layers of paint. His early paintings would later serve as literal grounds for new paintings. As he painted he would often add sheets of paper to the edges of the work, accumulating space. At times these would become part of the image, at others they remained simply a context out of which the final work emerged, a fragment of the larger material–just as each image was a fragment of an experience, a marker of a complex physical and psychological space. For Burchfield’s accumulations included the vast array of mental difficulties and imaginations that accompanied the external and visible world, like a chorus of crickets that could never be located but was emphatically present.

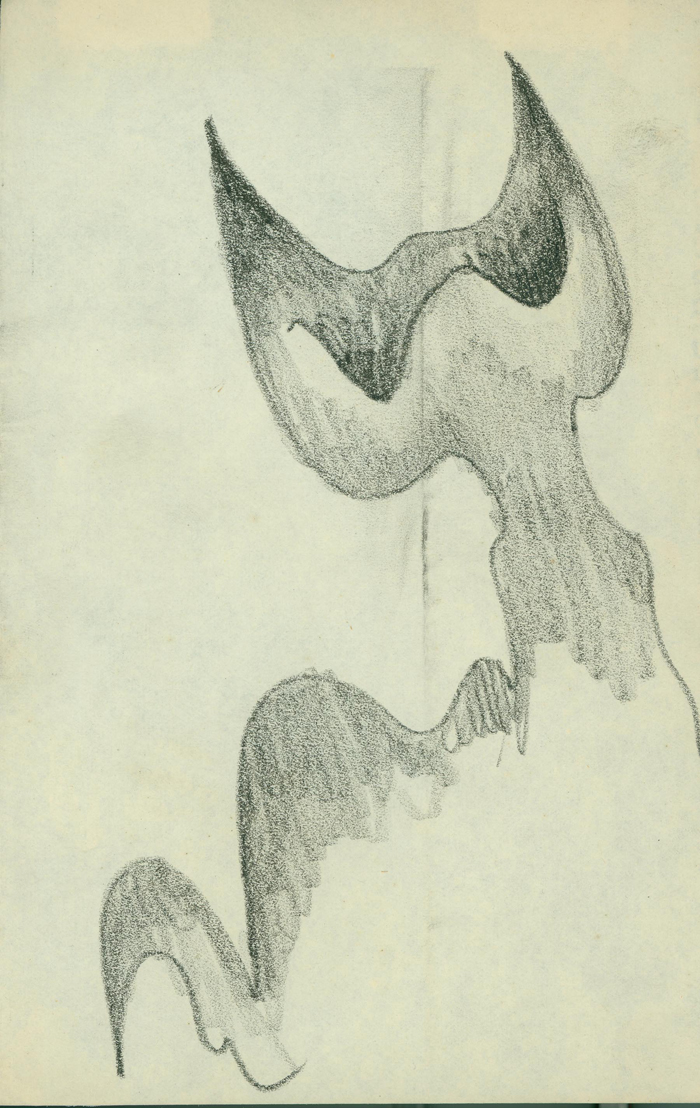

In 1916, he began a series of drawings in which he explored the material possibilities of the immaterial. These “conventions for abstract thought” presented visual forms for a variety of invisible sensations, fear for example, as in The Fear of Loneliness (1917). These studies reflected an ongoing interest in recognizing internal experiences as well as those of a more concrete nature. In a journal entry from 1911, Burchfield wrote, “In writing a diary I first thought that only events should be written; then gradually I began to put descriptions in which led me to describe my feelings at seeing different scenes and objects; now I think I ought to put in my imaginings, for they are part of a person’s life.” The weight of this invisible realm in Burchfield’s work becomes apparent as it is manifested materially in words, in journal upon journal over the course of his life. A stack of facsimiles of these journals graces the center of the final room of the exhibition. * A glass-enclosed vitrine encases bound and closed notebooks that function as metaphorical stand-ins for the still inaccessible mind, even as the walls shine with Burchfield’s own reckoning with psychological space in painting.

Charles Burchfield, Untitled (Fear 2), from Conventions for Abstract Thoughts, 1917. China Marker on paper, 81⁄2 x 55⁄8 in. Burchfield Penney Art Center. Gift of the Charles E. Burchfield Foundation, 2006.

The exhibition follows Burchfield’s career in roughly chronological order–through drawings, paintings, doodles, and commercial work–and ends with a series of paintings from late in his life, each weighted with the process of accumulation. Across this spectrum of practice, Burchfield anchored his visual media to the landscapes of his experience. Most of his work portrays the everyday natural world as encountered in an early twentieth century life, first in Ohio and later in upstate New York. These spaces became a field in which Burchfield grappled with his existence, which was often a struggle. At times, the link between the external and internal are strikingly literal in Burchfield’s work, as in The Night Wind (1918) where the landscape literally morphs into a monstrous shape, blackness setting a tone of unease. White Violets and Abandoned Coal Mine (1918) is even more striking in its depiction of a dark, gaping hole as subject. This capacity for visual metaphor, “conventions of abstract thought,” served Burchfield well over time. In the 1930s he took a commission from Fortune to portray modern industry. He depicted it as dark and somber in its labor, such as in Black Iron (1935), and The End of the Day (1938).

Charles Burchfield, The Night Wind, 1918. Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, 211/2 x 217/8 in. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of A. Conger Goodyear, 1960.

But Burchfield’s natural world is often more subdued in subject matter, less didactic in its intent. He proposed, “[I]t is as difficult to take in all the glory of the dandelion, as it is to take in a mountain or a thunderstorm.” Speaking to the complexities of representation itself, Burchfield’s comment also reflects upon the profound aspects of a seemingly pedestrian natural environment–a dandelion seedpod as an impossibly delicate and robust sphere capable of taking to the wind, as rendered in Dandelion Seed Heads and the Moon (1961-65). A weed becomes as microcosm of both the natural structure of the world and of our desire.

In the 1937 painting View of the Garden Plants beyond the Fence, Burchfield depicts rows of organized nature just out of reach, as vertical fence railings mark the plane of the canvas like bars. Separate but intertwined, nature both recedes from and shares space with the plane of our perspective. Here is the unbridgeable gap and inextricable link between our internal selves and external experience. Here also is the potential of Burchfield’s natural subject matter: seemingly singular events layer complex aesthetic possibilities and become multiple. By this point in his career, seasons, even years, combine in his landscapes. A series of works from 1943 emerges from those of 1917, and sets up a working method where works routinely encompass multiple decades. These chaotic but singular images reflect shifting temporalities and moods, accumulations across time. If, for example, The Coming of Spring (1917-1943) promises a new birth in 1943 from its original start of 1917, this spring, or reemergence, will be inextricably linked to the darkness and coldness of winter, and of war.

Walking through the exhibition raises the question of what we accumulate and what we discard as the years wear on. Such is the process of history itself, and although Burchfield sits staunchly ensconced in history, with the honor of being the subject of the first one-person exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1930, this current exhibition marks the first monographic exhibition for the artist on the West Coast, and arguably his first substantial introduction to the contemporary realm. Why in classrooms, in surveys, in discourses, and in theories of art and its histories have we not accumulated Burchfield? Perhaps this exhibition will affect that historical choice. Here is an artist who insisted on the vitality of representation in an era of abstraction; whose abstracted designs for wallpaper also bring the question of pattern and decoration to the fore; who addressed the psychological at the moment of surrealism and with certain resonances with that endeavor, although distinct; whose Christmas cards and Johnnie Walker ads speak to the role of the market in American culture; who in an age of big industry created small watercolors that you might just want to hold, as Annie Philbin, Director of the Hammer, did when she picked up a Burchfield in curator Gober’s home for a closer look. Accumulating both the possibilities and burdens of the twentieth century into his practice, Burchfield is a refreshing window onto questions of art that are strikingly contemporary.

The story of this exhibition begins with a cocktail between an internationally renowned artist and a dynamic director, and becomes one of how casual admiration became immersion. Once Gober began to talk to Philbin about Burchfield, he decided to propose an exhibition. The end result reveals one artist’s admiration for another, and the depth of Gober’s engagement is evident in the depth of knowledge we gain about Burchfield from the exhibition. The question remains as to how to think of the relation between the two as artists, for their intersection seems to be something other than mere influence.

Charles Burchfield, Sun and Rocks, 1918–50. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 40 x 56 in. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1953.

Consider the following trajectory. In the 1920s, Burchfield made wallpaper for M.H. Birge & Sons. The resultant patterns, one of which papers a room in the Hammer exhibition, are striking in their intensity and color. Burchfield seems to have projected his own understanding of nature’s patterns and their relation to the darker sides of psychological space into the unsuspecting middle class home as so many sunflowers. It is hard not to immediately think of Harold Rosenberg’s critical evocation of “apocalyptic wallpaper” in the 1950s. Considering the failure of certain abstract gestures, Rosenberg determined “wallpaper” to be an understandable and appropriate invective against surface decoration. Gober’s hanging of Burchfield’s Pyramid of Fire (Pyramid of Flame) (1929) on the papered walls makes such a leap to the apocalyptic quite literal. Which is to say that long before “wallpaper” might have been an insult to a painter, Burchfield had already made it interesting. Presumably, Gober finds that interesting as well. Rosenberg’s term in turn becomes the title of a 1997 exhibition at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Apocalyptic Wallpaper, in which wallpaper is recuperated as a generative realm for artists; Gober is included in the show. Evoking Marcel Proust and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, among others, in order to speak to its profundity, the curators chose wallpaper as an appropriate refusal of modernism’s white walls. Gober’s curatorial choice to juxtapose fire and wallpaper also relates to Gober’s childhood, when the repainting of his home after a fire resulted in a trompe l’oeil scene on a wall. Similar scenes began to show up in Gober’s installations in the 1990s. For example, a 1992 exhibition at the Dia Center for the Arts included a large-scale forest along the walls. The installation functioned to confuse the external and internal realms, and to explore the difficult interconnections between the two. It also featured a barred window that resonates with Burchfield’s own barred view from the porch to the garden in View of the Garden, a painting which Gober frames prominently in the exhibition.

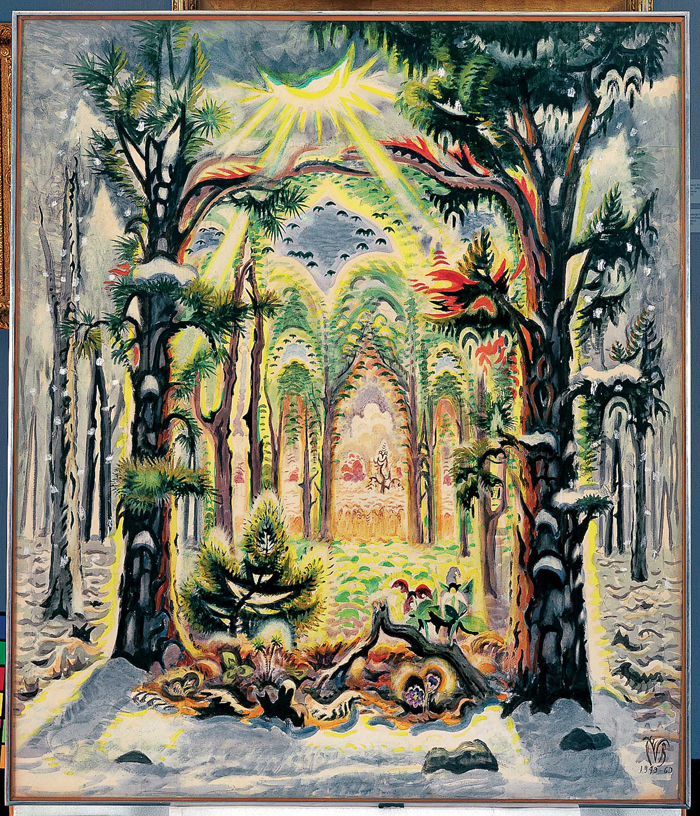

Charles Burchfield, The Four Seasons, 1949–60. Watercolor on pieced paper mounted on board, 557⁄8 x 477⁄8 in. Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavilion, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Festival of Arts Purchase Fund, 1961.

To see Gober’s Burchfield in 2009 then, is to be left in contracting time and space–from the artist’s studio in the early twentieth century to the great urban megapolises of Los Angeles and New York and their professional art worlds; from the artist as painter to the artist as curator; from artist to artist; from the external to the internal; and from the role of landscape in one practice to another. In thinking about how to paste all of this together, we might think of Burchfield’s process itself: adding and subtracting paper to the edges of the image in order to provide the conceptual space we need, picking up an idea seemingly decades old and reworking it again and again. Years exist on one plane. Perhaps the historians among us should take note.

Here then we might also return to the landscape, an arena in which change is constant and marked–across seasons, over years, from the effects of industrialization– exactly because of its grounding in space, in place. Each year recurs anew but resonates with the one before in the space of Burchfield’s experience, and in the landscapes to which he was drawn. October in the Woods (1938-63) speaks to this repetition of an event in a place, both familiar and new year after year. The landscape as genre was a place in which Burchfield could map his experience, in which he could anchor his imaginations and his conflicts, and in which he could accumulate himself over time. To do so was also a process of reworking. It is a reminder that to experience is to look, and to look again.

Jane McFadden is an art historian of modern and contemporary art. She serves as Assistant Professor and Director, Art and Design History at Art Center College of Design.

* The published volume of journal entries, Charles Burchfield’s Journals (1993), has a respectable material presence as well; it is a weighty, 700-page tome.