Philip Guston, Untitled, 1971. Oil on paper mounted on panel, 29 × 40 in. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of the Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

If Philip Guston’s 1970 trip to Rome wasn’t conceived as an escape from humiliation, it served that purpose. His first few months as artist-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome were spent in recovery mode after the opening of his October 1970 show at Marlborough Gallery and the round rejection of his astonishing new figurative paintings by the New York art world. Despairing and searching, he wandered Rome, revisiting the old-world art so formative to him in his youth. Then, at the turn of the new year, he got back to work.

A new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles unites two significant series undertaken in this year of recuperation and return. The Roma paintings are a set of forty-three modestly luminous oil-on-paper works produced during his residency at the Academy. The Richard Nixon drawings, nearly two hundred joyfully grotesque illustrations of the president and his accomplices, were created upon Guston’s return home to Woodstock, New York. These include the seventy-seven he selected for the Poor Richard series, which had initially been planned as a book until Guston thought better of publishing it. (The images were not shown publicly during his lifetime.) Curated by Guston’s daughter Musa Mayer, Resilience: Philip Guston in 1971 asks: Who was Guston and what did he produce in the aftermath of what he described as his “excommunication” from the art world?1

In spite of their temporal proximity, the Roma and Nixon series, both of which have been shown separately in various assemblies, initially seem to present two very different Gustons. The Roma paintings offer evidence of the painter regrounding himself in his practice after his upsetting (albeit temporary) tumble from art world eminence. Chronicling his evolution as a figurative painter increasingly favoring objects, the works are grouped into four categories: Hoods, featuring Guston’s iconic Klansmen; Forms, charismatic studies of stones, sticks, and other found shapes; and Ancient Fragments, followed by Gardens and Landscapes, which together capture a range of sites and structures seen during his explorations of the city, many of which play with scale and composition to subtly comic effect. These are displayed in the first two rooms in one wing of the gallery’s complex.

Marching merrily across the other wing are the Nixon drawings, satirical images that launch furious, mirthful shots at the pre-Watergate president. Compared to the vibrant yet muted object studies of the Roma paintings, the Nixon drawings are freewheeling and frenetic, louder, and less studied. Together, the two series show Guston redoubling his commitment to figuration and topicality in the context of a modernism that largely spurned both.

“There are times in one’s life that you begin, all over again, from the beginning—a true turning over—a heave in my case,” Guston observed after his decisive break from abstract expressionism in the late 1960s. “As if I had metamorphosed again, perhaps from something in flight into some kind of grub.”2 The break, which came after a mid-career Guggenheim retrospective and, by all accounts, tremendous success, was motivated by a sense of his own political futility as an artist. “When the 1960s came along,” he said later, “I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”3 Amid the cultural upheaval of that decade, from the civil rights movement to the Vietnam War and the rise of Richard Nixon, Guston became convinced of the impotence of abstract expressionism. He pivoted resolutely away from the constraining purity of that school and toward a winking, flatly figural mode that combined his earlier social realist work as a muralist with his love of caricature and cartoons.

The initial critical response to this late-stage “heave” registered suspicion at Guston’s seemingly abrupt transition from one thing to another, apparently having forgotten that this was not Guston’s first metamorphosis: an earlier transition, from figuration to abstraction, occurred during his first stint at the American Academy in Rome from 1948 to 1949. Of course, periods of transformation occur in most artists’ careers; more interesting, perhaps, is how Guston deployed transformation as a key element, even a pursuit, of his visual approach. In a conversation with poet Bill Berkson, Guston described his late paintings as “not pictures—but a ‘substitute’ world which comes from the world.”4 This surrogate reality appears distorted, de-realized, and populated by invented and uninvented characters. In a context where any return to representation was considered a regression, Guston dug in his heels and painted regressively with gusto, combining deliberately naive figures with flat perspective and distorted scale to transform reality into something else—maybe even “some kind of grub.” Where many of his contemporaries still burdened art, and painting in particular, with the obligation to transcend the real, Guston’s new work proposed a kind of reverse transcendence enacted formally and rooted in the personal and the topical. In Resilience, we see Guston doubling down on this break with abstraction’s purism and embracing more firmly the crude and the cartoonish.

Guston’s original dumb, lumpen Klansmen were sensational and unnervingly ambiguous, their hateful inclinations undercut by their dopiness, their terrifying significations transformed into unsettling, uncertain comedy. In Flatlands (1970), for example, two hooded figures ghost a violent scene, their triangular bodies roving menacingly like shark fins rising from a sea of bloody debris. But where sharks are calculating, these hoods are witless, crude—their eyes twin exclamation marks with no dots, their faces unblinkingly blank. Flat hoods, flat clouds, a flat sun, a flat gloved, pointing hand: Flatlands is busy, irregularly scaled, the canvas a dumping ground for disparate objects and events. Behind a salmon-colored clock, the legs of a body sprawl, a pose that recalls the four students massacred by the National Guard at Kent State University, Ohio, on May 4th of that same year.

Philip Guston, Flatlands, 1970. Oil on canvas, 70 × 114 1/2 in. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Byron R. Meyer. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel.

Guston grew up in Los Angeles, where he sustained his first terrifying encounter with the Klan as a Jewish kid witnessing a KKK parade in the 1920s. When he debuted his hood paintings in 1970, Klan iconography was considered as dated as the social realism of Guston’s 1930s work, some of which also featured hooded figures. Shadowy and grim with old-world shades of the Inquisition, these earlier hoods represent unequivocally the evils of persecution. By comparison, his newer hooded figures are more morally ambiguous, symbolic at once of rogue racism and white vigilantism, of hate-driven antiauthoritarianism, of unrestrained bigotry and anonymized terror, of malignant, unaccountable buffoonery—and of the potential evil lurking in all of us. “What would it be like to be evil?” Guston said in a 1978 talk. “To plan and plot.”5 Guston drew connections to cinema, speaking of himself as a filmmaker setting stories in motion. “I was like a movie director. I couldn’t wait.”6 He envisioned himself living with the Klan, a thought experiment that led him to conjure a shadow city overrun by Klansmen and to develop a cast of characters, some of whom were artists like him. There they are, on the way to a cross burning (Central Avenue, 1969); driving away from a pile of bodies, white hoods spotted with blood (Dawn, 1970); flanking an enormous bottle of liquor, one hood threatening to whip the other (Bad Habits, 1970). There’s another, solitary in a wooden chair, his head fallen on one red hand, lit cigarette in the other (By the Window, 1969). And again, alone in the studio, painting a self-portrait (The Studio, 1969).

Plopped into this surrogate world, Guston’s paragons of flatness were caricature more than character. Reviewing the Marlborough show in The New York Times, critic Hilton Kramer dismissed the hood paintings as “cartoon anecdotage,” a description both contemptuous and accurate.7 Guston had turned away from abstract expressionism not towards realism but towards another anti-mimetic mode: cartoons and comics. Yet, though he was indebted to both traditions, having grown up with a love of Krazy Kat, Mutt and Jeff, and Mickey Mouse, Guston distanced himself from their influence, aware of their status as “low art” and their denigration by critics like Kramer.8 In fact, Guston’s decision against showing the Poor Richard series in his lifetime was largely motivated by the reasonable fear that it would lead to more charges of lamentable “cartoonishness” against his paintings.9 Even as his turn to the cartoonish was in part a sharp rejection of prevailing aesthetics, his subsequent rejection by the art world was upsetting enough that he had no desire to repeat it.

If the Marlborough show and its scenes of grubby, hooded Klansmen were the beginning of Guston’s imagined film, the Roma paintings see the film nearing a tentative end. Neither as widely shown nor as frequently written about as their Marlborough counterparts, the smaller, late-stage hood paintings of 1971 augur a phasing out of these icons from Guston’s visual vocabulary, perhaps suggesting they had approached the limits of their capacity as ambiguous signs. Now that the spectacle of their appearance had dimmed, Guston’s uncomfortably comic troublemakers no longer made much trouble. In Rome, as Jeffrey Cudlin notes in his review of a 2011 exhibition of the Roma paintings, the hood has its own set of meanings, associated with freethinking martyrs like the sixteenth-century cosmologist Giordano Bruno.10 In Guston’s Roma works, the hoods seem incapacitated, immobilized, even grieving. In Untitled (Rome) (1971), twin hoods huddle together, the usual eye slits converted into dark pyramidal windows. These hoods appear to have blended into the architecture: concretized, they stare out mournfully, beseeching, their bodies taking on the pained pink of a Rome still reckoning with the legacy and collapse of Italian fascism just twenty-five years prior.

Philip Guston, Untitled (Rome), 1971. Oil on paper mounted on panel, 19 × 27 1⁄2 in. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. Private Collection. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

The hoods on display in Resilience are anxious, uncertain lumps, neither as smug nor as laughable as their predecessors. If Guston’s 1971 hoods are less actively violent, less sensational than their predecessors, they are still bloody—indeed, seem to sweat blood. In another 1971 painting called Untitled (Rome), the first of two paintings that, as arranged, invite a sequential reading, a blood-stippled hood points at a floating piece of paper torn out from a notebook. In The Picture (1971), the (same?) hood is locked into place within that piece of paper. A signature Guston hand enters the frame to offer the hood a cigarette.

These new hoods read as abject remnants, not unlike the ruins that are integral to the Roman landscape. As the show progresses, the hoods fade out and other forms take over: stones, tablets, fragments of statues. These forms presage the objects that Guston obsessively gathered in his late work: shoes, lightbulbs, mugs of coffee—the shapes that made up his life. Like the hoods, the Roma objects have a subtle humor, not just in their crudely brushed forms but in their friendly, imperfect shapes and crowded, disproportionate arrangement.

Philip Guston, The Picture, 1971. Oil on paper mounted on panel, 30 × 39 1⁄4 in. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. Private Collection. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The hoods return, in a pointed reprise, in Poor Richard, no longer actors themselves but as costumes for actors on the world stage. The hood is one of several outfits Guston gives Richard Nixon and his dimwitted sidekick Spiro Agnew by way of ridiculing their general hoodwinkery. Here the hoods are not as ambiguous or philosophical as Guston’s cartoon Klansmen; rather, akin to his earlier expressions of the Inquisitor-era persecuting hood, they illustrate his sense of Nixon’s “overt racism, homophobia, sexism [and] anti-Semitism,” which would soon emerge barefaced in the Watergate recordings, as well as his hypocrisy.11 What’s beneath the hood? Guston depicts Nixon tilting back Agnew’s head, and vice versa, revealing only emptiness. When they no longer confer any advantage, Nixon and Agnew dump their hoods in a trash can.

Resilience: Philip Guston in 1971, installation view, Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, September 14, 2019–January 5, 2020. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of the Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

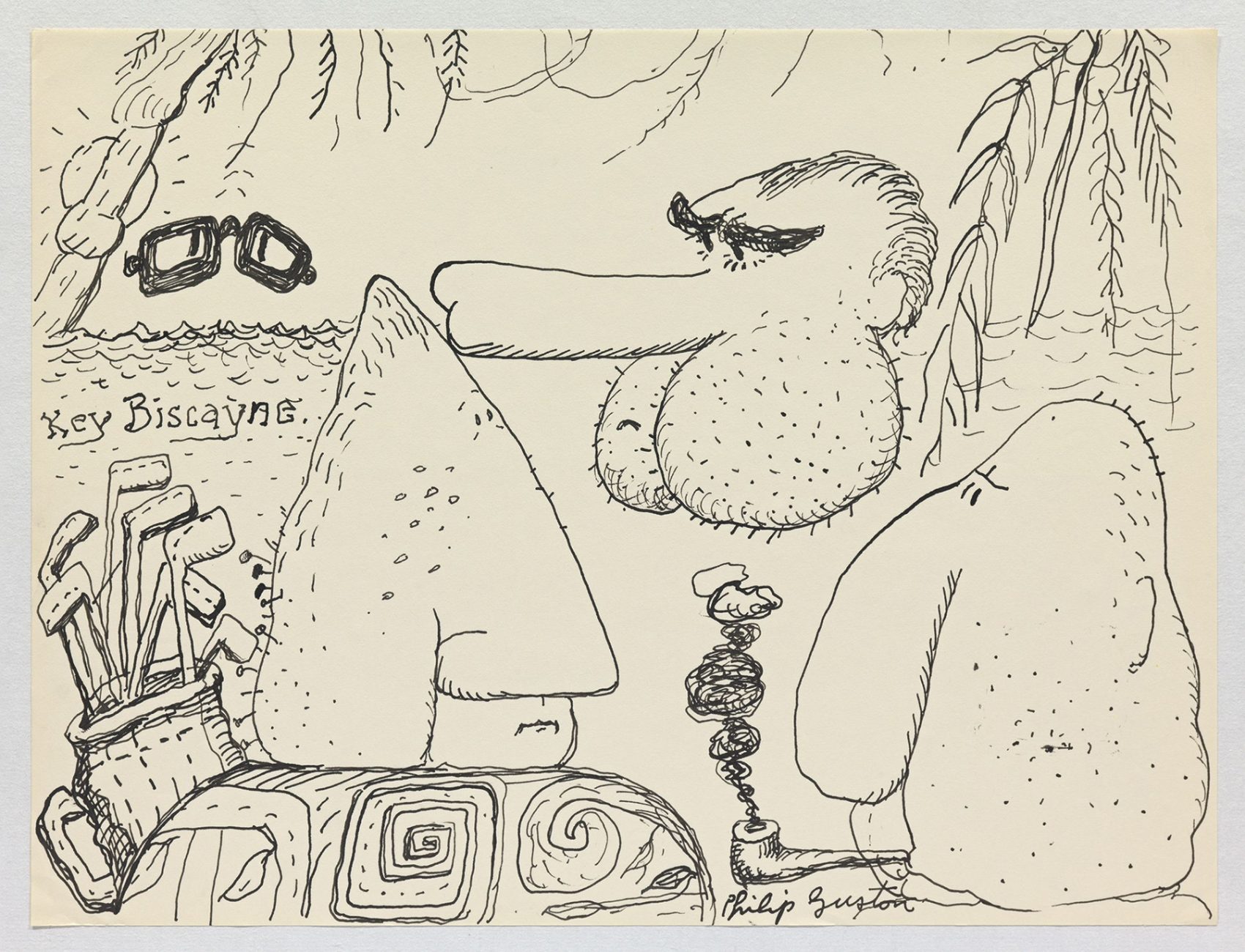

As hooded figures, Nixon and Agnew are grubby and grotesque, bulbous and pale. Indeed, the seventy-seven drawings that make up Poor Richard are exuberant in their ugliness. They feature a Nixon whose Pinocchial nose grows longer and more penile as the series progresses, his drooping jowls manifesting as a hairy scrotum. His entourage includes a cone-headed Agnew with nails hammered into the scruff of his neck and a droop-faced, pipe-puffing John Mitchell; meanwhile, Henry Kissinger floats around disembodied, emblematized by his signature horn-rimmed glasses. The sequence is ingenious and at times quite bizarre.

Produced during the runup to Nixon’s reelection in 1971, after the Pentagon Papers but before Watergate, after the announcement of the historic trip to China but before it took place, Poor Richard possesses remarkable prescience. A loosely narrative work of furious, no-holds-barred satire, the series begins as mock political biography, charting Nixon’s political rise from boyhood to the presidency. It follows Nixon to his favorite presidential retreat, Key Biscayne, Florida, where he bobs and schemes, conjuring scenes from the anticipated China trip, which would be the first visit by a United States president since China’s communist takeover in 1949. In the same way he imagined his hood paintings as scenes in a film, Guston casts Nixon and his henchmen in all kinds of marvelous scenarios: at a Halloween party, with Agnew and Mitchell as crooks and an uneasy Nixon vying for Black votes in blackface; Nixon in China, slurping up food with his proboscis.

Philip Guston, Untitled, 1971. Ink on paper, 10 1/2 × 13 7/8 in. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of the Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

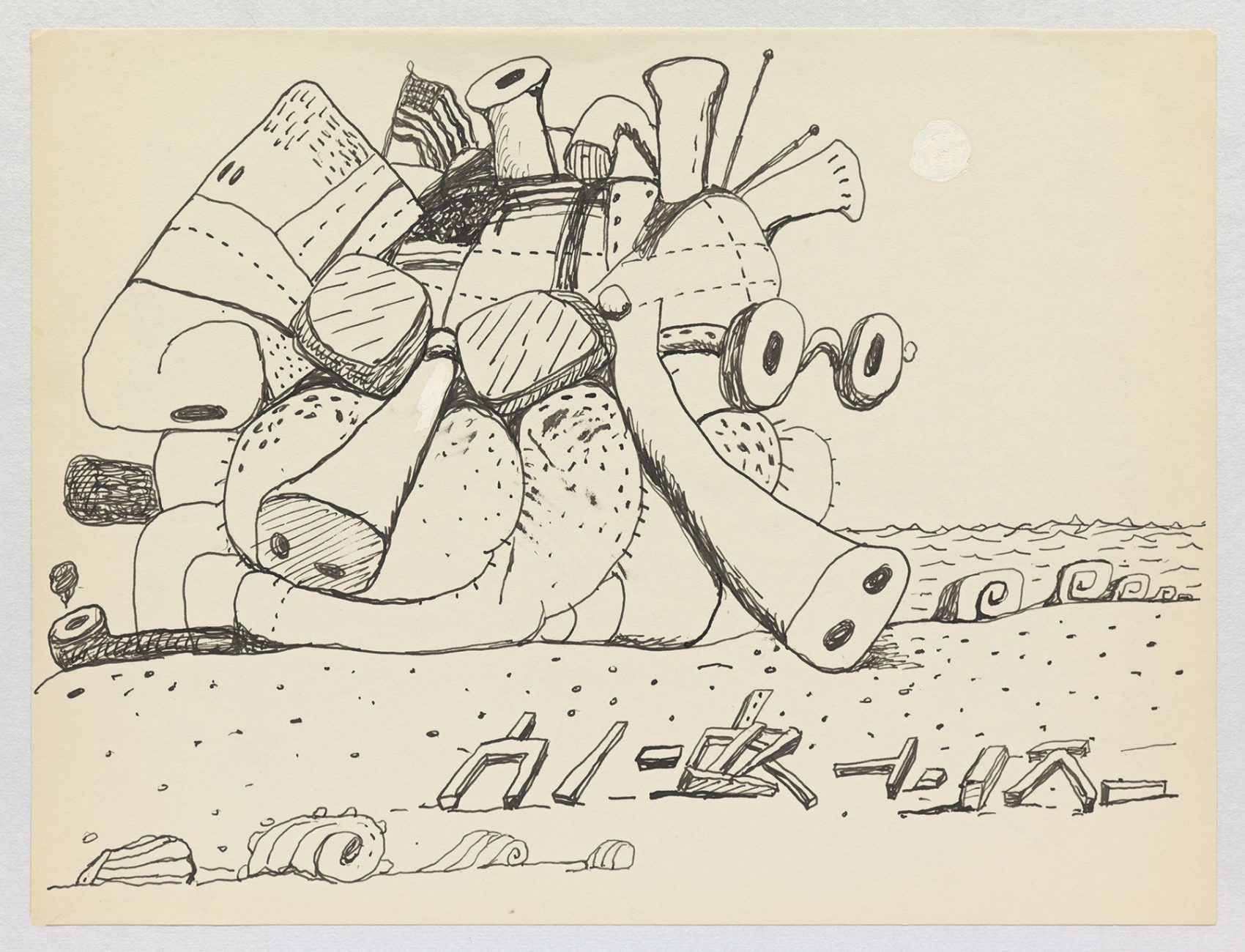

Resilience exhibits dozens of other Nixon drawings, too: many of them likely studies for the series, others one-offs and interesting in their own right. In Untitled (1971), Nixon, Agnew, and Kissinger are piled into a giant tangle of heads, their noses protruding like arteries to a three-chambered heart, or like bagpipes ready to be blown—a clump that anticipates the knots of boots and limbs that characterize some of Guston’s later paintings. In a similar image in the final sequence, the tubular noses become the muzzles of cannons and guns. As they do in his paintings, objects gain animacy, like Kissinger’s glasses skittering nervously across the scenes like overgrown spiders. Similarly, where in his paintings he obsessively repeats forms like hoods and boots until they transform, here Guston repeats his “Tricky Dick” visual pun until Nixon himself seems to get exorcised through transmutation into a containable form.

Philip Guston, Untitled, 1971. Ink on paper, 10 1/2 × 13 7/8 in. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of the Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

The first public viewing of Poor Richard, at the McKee Gallery in New York, opened on September 7, 2001, and was quickly overshadowed by the September 11 terror attacks. The sequence has been exhibited a number of times since then, most recently in 2016 at Hauser & Wirth in New York, opening before the general election and producing different resonances before and after Trump’s then-unfathomable win. Attending on November 1, 2016, critic Sarah Cowan reports, “It drew an amused crowd of boomers and millennials, the distance in their experience bridged by the convincing sense of security many of us had that doomed week.” A month later, “the drawings had turned on us: a joke at the expense of our smugness.”12

One legacy of Guston’s post-1968 work is its function as a barometer of cultural pressures and political turmoil. During Resilience’s run in late 2019, in the lead-up to the next presidential election, as the House planned to send articles of impeachment to the Senate, Guston’s sequence about a crooked, untrustworthy president in a pre-election year seemed timelier than ever. Likewise, in a fraught cultural moment defined by resurgent white nationalism and an unending barrage of domestic terror incidents, Guston’s hoods have again become contemporary. The late artist’s metamorphosis into a cartoonish, anecdotal figurative painter and creator of weird satirical worlds was not only coincidental with his historical moment, but an urgent and necessary response to it. So, too, thinking about his work in these terms is urgent and necessary now. In this sense, the exhibition’s title is apt. Letting go of the impulse to transcend the real, Guston instead used art to be present and resilient within it.

Poor Richard envisions Nixon’s presumptive dream of seeing his mug, along with those of Agnew and Kissinger, carved indelibly into Mount Rushmore. As a substitute for this laughable fantasy, Guston gives Nixon and his cronies two other speculative legacies: first, as fractured sculpted heads, reminiscent of the ancient ruins Guston painted only months before; second, as American novelty foods, “Kissinger Pot Pie,” “Spiro Sponge Cake,” and, in the series’ hilarious final image, the “Nixon Cookie.”13 What form would Guston give our current leader, who so readily seems to satirize himself? Perhaps the Trump “Hamberder.” Trump Taco Bowl. Trump Corn on the Cob. Plenty of Internet memes have transformed Trump in similar ways—but none, perhaps, with the vicious wit and crude imagination of Philip Guston.

Megan Milks is a Brooklyn-based writer and critic.