Catherine Opie, In Protest to Sex Offenders 2005, 2004-2005. C-print, 16 x 20 inches image size. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Catherine Opie’s work first leapt to prominence through her 1993 series of portraits of the queer leather punk and dykes who formed her community. Luscious polychromatic photographs of alternative dykes, FtoM transsexuals and drag queens in their twenties unflinchingly returned the viewer’s gaze in classic formal compositions, both intimate and distanced. One self- portrait had Opie in a leather hood, shirtless, with the word “pervert” carved into her chest; a second was of Opie’s back with a carved picture of two women holding hands in front of a storybook house. A year later Opie’s Freeways series offered a powerful counter-punch: small, elegant, highly formal platinum prints of L.A.’s sweeping and monumental freeway interchanges in a golden light without traffic or humans, images even more formal but retaining a strange conjunction of intimacy or nostalgia and distance. In these two strokes Opie became known as a virtuoso of both the portrait and the landscape, working through serial projects (iterations of a typology, such as houses or mini-malls) whose formality belies a basic set of socio-political questions that underlie and connect each set of images.

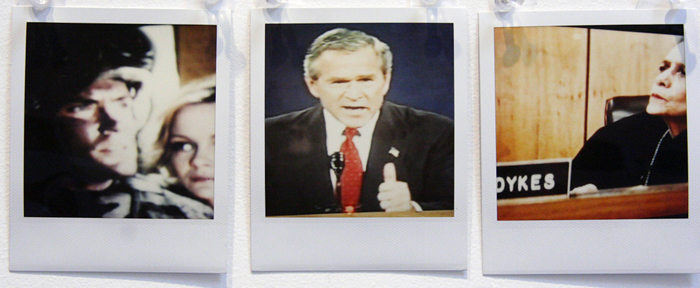

Over time however, it has become evident that her driving concerns exceed those of documentation and conceptual art, just as they have come to disregard the polarities of landscape and portrait. At the heart of Catherine Opie’s current show at the Orange County Museum of Art is the idea of home in its expanded sense—not just the house you live in, but your home within its social context and neighborhood. The title of the museum show, In and Around Home, is taken from the title of Opie’s 2005 series of photographs, which form the core of the exhibit: a set of 42 domestic and neighborhood images taken over the span of a year or so, “in and around” her home. House and Homeland are a heartbeat apart in this show, with Polaroids of George Bush on television punctuating the lush c-prints of the artist’s home and neighborhood, grounding a meditation on wartime America and Angeleno urbanism.

Catherine Opie, Dickason Family, 1988. C-print. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

The idea of community has woven through virtually all of Opie’s projects. In and Around Home has a layered, essayistic quality more critical than any of her work since graduate school and conveys a pungent sense of urgency around the political direction of the United States. The Polaroids include other topical issues of the last year such as the death of Pope John Paul and the polarizing Terri Schiavo case, an example of extreme media manipulation that penetrates to the core of personal issues such as the right to live and die as one chooses. These are balanced against lyrical domestic portraits of Opie’s home with her lover, artist Julie Burleigh, and their son, Oliver, as well as more documentary shots of their West Adams neighborhood, racially and economically mixed or “transitional,” as real estate agents call it. One triptych of c-prints captures three local events—the Martin Luther King Parade, the USC Homecoming and a street protest against a sex offender residing nearby. These three images resonate strangely together, and the viewer is especially drawn to the protest against the sex offender; hand-drawn signs object that even one known sex offender is too many, calling attention to the way in which a neighborhood, even one as eclectic as this, is still constructed in part through exclusion and scape-goating: certain perverts are not welcome here.

The OCMA show is a survey that spans seven of Opie’s major projects over the last twenty years, including the first public exhibition of her CalArts MFA show, Masterplan (1986-88). A broad, critical documentation of the planned community of Valencia, Masterplan studies the strategies and ideological structures of master-planned suburban developments. It’s a close look at white flight, documenting two families, the Dickasons and the Troidals, almost as a way of taking the pulse of the community. One more proper and bourgeois, the other more blue collar, the families are examined both in the portraits Opie takes of them, as well as through interior shots of their homes—one quite neat and the other messy. The Dickasons’ stiffness is underlined in the juxtaposition of Opie’s rather formal portrait of them with a photograph of the living room that includes a cold, waxen oil portrait of them on the wall. While not overtly judgmental, the two family portraits give the sense that the Troidal family members, slouching together on their sofa, are more comfortable in their skin—and their home.

Catherine Opie, Days, Thumbs Up, and Judge Dykes, 2004-2005. Three Polaroids, 11 x 17 3/4 inches. Unique. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Masterplan is a nice contrast to Opie’s recent work, showing how true her focus has remained while revealing a turn away from serial typologies and documentation toward a more eclectic, critical photo-essay. But In and Around Home was originally meant to be paired with the series 1999, which does not stand up to it as a consideration of home. A moody set of 28 images embarked upon in the all-but-impossible task of capturing “iconic” America on the verge of the new millennium, most of 1999 looks back to a rural America of shuttered storefronts, lonely landscapes and weathered signs that we recognize from the work of Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and William Eggleston. More a study in nostalgia than on the idea of home or even community, what is most notable here is the prospect of a lesbian revisiting this mostly masculinist territory, provoking reflections on how male-centric the iconic American road trip is. Still, one might ask what is this lone lesbian photographer traveling toward, or away from? These images investigate a set of male modernist sensibilities as they haunt both photography and the American landscape.

Notably missing from the OCMA show is Opie’s series Domestic, a set of casual interior portraits of “ordinary” lesbians and their families across America, which I believe was made on the same cross-country road trip in 1999. Though they are cited in the curator’s statement, Opie’s early queer Portraits, focused as they are on identity, are not as noticeable in their absence as Opie’s significant body of work on lesbian domesticity. The one portrait missing here is arguably the self-portrait of Opie’s back with the carved lesbian couple and the little house—perhaps a commentary on home so blunt it would derail the show—but Domestic probingly ties in questions of identity with those of the home. The wall placard for In and Around Home identifies Opie as a “lesbian mother,” but the viewer might miss the fact that she is part of a lesbian couple if he didn’t scrutinize the images. There is no family portrait at the end of In and Around Home. Instead we find a trio of related portraits of Opie, her lover, and her lover’s grown daughter, each playfully posed with a different pet dog. The family in this house doesn’t want a formal portrait, and one clue as to why might be found in the chilly family portraits of Masterplan. In place of an idealized nuclear family, these recent images propose a looser confederation of individual interests, negotiated as much in a sense of tradition as by a sense of play.

Catherine Opie, Oliver in a Tutu, 2004. C-print, 24 x 20 inches image size. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Conceivably in place of Domestic, the Orange County exhibition includes Opie’s 2003 series Surfers, which is the weak link in a show otherwise well curated. It somehow stands apart, with one wall of crisp portraits of a great variety of surfers of various ages, races and genders, facing another group of images of just the water with hazy groupings of surfers waiting for a wave. No doubt they were included because they depict a sort of iconic nomadic community with all its utopian potential, but their interrogation of home is minimal. Beautiful images, well mounted, but out of place in a show otherwise well thought through. The exhibition’s other series, Houses (1995-96), flat façades of the fancy mongrel architecture of houses in Bel Air, contrasts provocatively with Mini-malls (1994-95), strangely affectionate black and white images of the ubiquitous LA mini-mall, with its hodgepodge of contemporary folk vernacular architecture.

Perhaps the defining image of Opie’s recent work in In and Around Home is “Oliver in a Tutu” (2004). The artist’s son stands on a chair by the washing machine, backlit by a ray of sun, and wearing a princely paper crown, a USC football t-shirt and a bright pink tutu. Revisiting all the questions of gender performance and identity in Opie’s original queer portraits, “Oliver in a Tutu” recasts the questions more lightly, in terms of play and domesticity; behind him a woman sweeps the porch steps, so the image is both wholesome and provocative. Compare this to the “Dickason Family” portrait (1988), in which the similarly blond son, also ensconced in his home, sits primly in a starched button-down shirt by his mother’s stiff knee, with his father standing ceremoniously behind them. Like the trio of portraits mentioned above, Oliver appears three times, but on different walls. Each time he is at play and curious, inhabiting a safe but open world that rectifies some of the harsh realities of both the neighborhood and the history of families.

Matias Viegener is a writer who teaches in the MFA writing program at CalArts, a founder of fallenfruit.org and co-director of an annual conference on experimental writing at REDCAT.