Much hubbub and a million positive reviews later (the LA Times alone covered this show three times), Masters of American Comics, the illustrious two-part exhibit co-hosted by the Hammer Museum and MOCA, has finally come to a close. Rarely have I heard so much discussion about the brilliance of a museum show. Who would’ve disliked seeing over 900 works of comic art by fifteen artists, including yellowed, turn-of-the-century newspaper pages; proofs delicately marred by artists’ blue pencil under drawings and whited-out mistakes; cases full of ephemera and out- of-print comic books; sketches that inspired some of the most classic comics ever rendered; and even some sculpture by Chris Ware? Some friends of mine made multiple trips in order to absorb the cornucopia of information. Others tamed the beast head-on by seeing the show’s two parts—the first half-century covered by the Hammer and the latter-half by MOCA — back to back. (In Milwaukee, the massive collection will be housed in a single venue and back East the two halves will be divided between Newark and New York City.) After reading endless press declaring that “Comics Are Finally Considered Art!” I can return to my crates of silverfish-infested comic books feeling slightly less isolated in my fascination with the genre’s newspaper-based beginnings and to wistfully reminisce about that time I got to see Winsor McCay panels in the papery flesh.

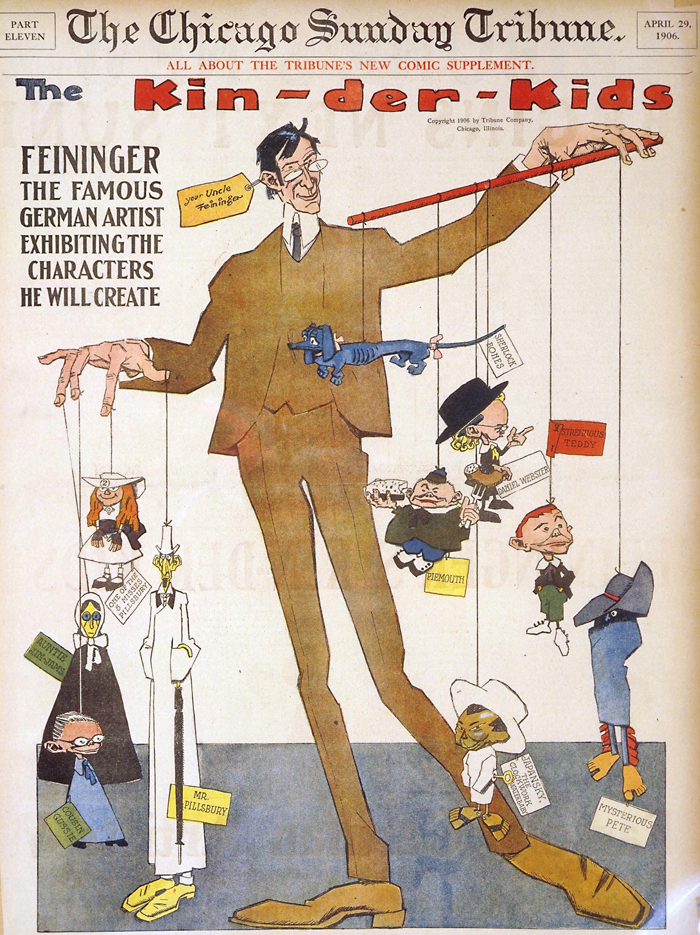

Inevitably, a critical controversy arose as a result of the one semi-elitist facet of the show: all the artists selected were white males, with the exception of African-American Krazy Kat creator George Herriman. How to avoid fiery debate when an entire world of female (think Julie Doucet) and non-white (Los Bros. Hernandez) comic artists are also considered pioneers in their genre? The artist selection process, however, was actually quite judicious. Co-curators Brian Walker, Cynthia Burlingham, Michael Darling, and John Carlin consulted Art Spiegelman before bestowing “master” status upon McCay, Lyonel Feininger, Herriman, E.C. Segar, Frank King, Chester Gould, Milton Caniff, Charles M. Schulz, Will Eisner, Jack Kirby, Harvey Kurtzman, R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Gary Panter, and Chris Ware. There aren’t many comic lovers alive who would dispute the qualifications of these selected few.

Intentionally assembled as a provocative museum exhibit meant to set a precedent for other shows to challenge, John Carlin told Art On Paper’s Leslie Jones that he wanted to create an “old-fashioned type of art exhibition that I would never organize or curate if I were working in the art field. I really felt the canon hadn’t been established in a coherent way. This attempts to do that and to create something that people can criticize and move beyond.” Moreover, Spiegelman was one of his own harshest critics, telling Modern Painters that he lamented the exhibition’s omissions, but that this was an “early draft of an effort to understand the typography of a medium that has its own needs and logic. Once comics get to storm the citadel, one will have room for all kinds of eccentric creators.” The main problem, as I saw it, was that this should have been the first part of a ten-part show. At least the citadel has been stormed.

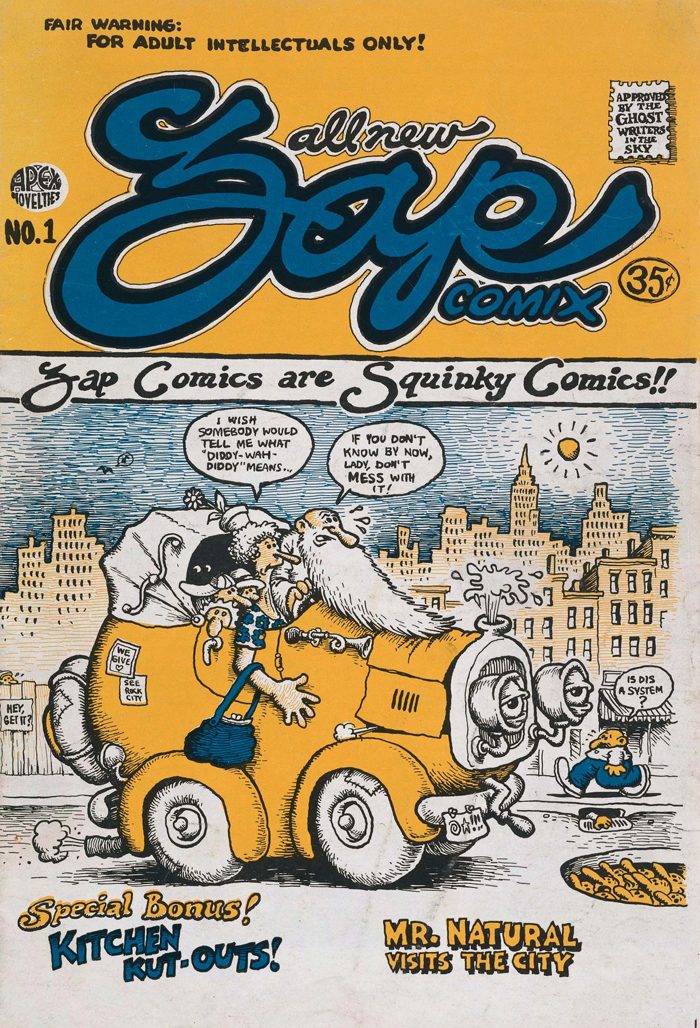

Simultaneous to the MOCA/Hammer exhibits, curator Brian Tucker took the cue to enact the first response to Masters of American Comics, in the form of a Love and Rockets show at Pasadena City College Art Gallery. The Hernandez Brothers are well loved primarily for their 65-issue run of Love and Rockets and for, consequently, helping to develop what is now known as the graphic novel through their perfection of soap-opera- like narrative in long-form comics. Perhaps more importantly, they’ve concurrently widened the indie publishing world’s role as a haven for freaks of all cultural varieties (Mexican-American in Los Bros. Hernandez’ case) as well as white, hippie, Zap Comics spawn (i.e. Crumb). “It was clear that the museum show was going to contain fantastic material,”Tucker told me via email, “but it was equally obvious that many worthy artists were not included, and there were some glaring categorical omissions, too: no women at all, and, with the exception of the very great but long dead George Herriman, no non-white artists and nobody from Southern California. Los Bros. are important figures in the history of comics…whose work is rooted in Southern California Mexican- American culture.

Tucker organized Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez’s art into a cohesive exhibit that both highlighted common themes in the Brothers’ work and helped to accentuate their stylistic differences. Walls dedicated to each artist showed original panels arranged in sequential narrative fashion, basically pulling apart their comics. A couch with coffee table piled with the books containing printed versions of the displayed panels enabled viewers to, as Tucker put it, “understand how a given page figured into a larger narrative.”Therefore, the show’s subject matter — featuring complex female protagonists, Latin American families, Southern California punk rockers, and characters with diverse ethnic backgrounds, sexual preferences, and economic classes, said the press release — made clear that the Love and Rockets exhibit was meant to provide a new, more elevated context for contemporary underground comics.

Masters of American Comics didn’t aim to concern itself too much with contemporary underground comics. Rather, the MOCA portion of the exhibit traced the historical development of an underground. Starting with panels of The Spirit by Eisner (clearly a huge influence on contemporary artist Raymond Pettibon), MOCA featured Marvel Comics man Kirby, MAD Magazine’s Kurtzman, and, of course, Crumb, as a way to set up the ‘80s as an historical moment when underground comics once again — following the 60s boom — became radical.

RAW magazine founder Art Spiegelman, Jimbo’s Panter, and Acme Library’s Ware were the elected spokesmen for the contemporary underground, since all three have cultivated the non-linear, abstract narrative style so popular in comics today. A humongous room split between Spiegelman and Panter housed issues of RAW magazines, oversized panels of Panter’s masterwork, Jimbo in Purgatory, along with some fantastic pen and ink collaborations between Panter and Charles Burns from their book, Pixie Meat. One surreal nightmare from this series showed a man getting stabbed in the brain by a knife while zombies lurked in the background. Ware’s room, much more subtle, featured Ware’s sculptures of invented characters and non-comic related oil paintings, but the real gems were his flatly-painted, somber panels for Rusty Brown, which exemplified his masterful use of type. The two words “Rusty Brown” repeated on each panel were transformed into art by Ware’s invention of various warped cursive and serif letters. In the center of the room, three huge cases held the plethora of books he’s made, proving that he is, hands down, a serious master of graphic design.

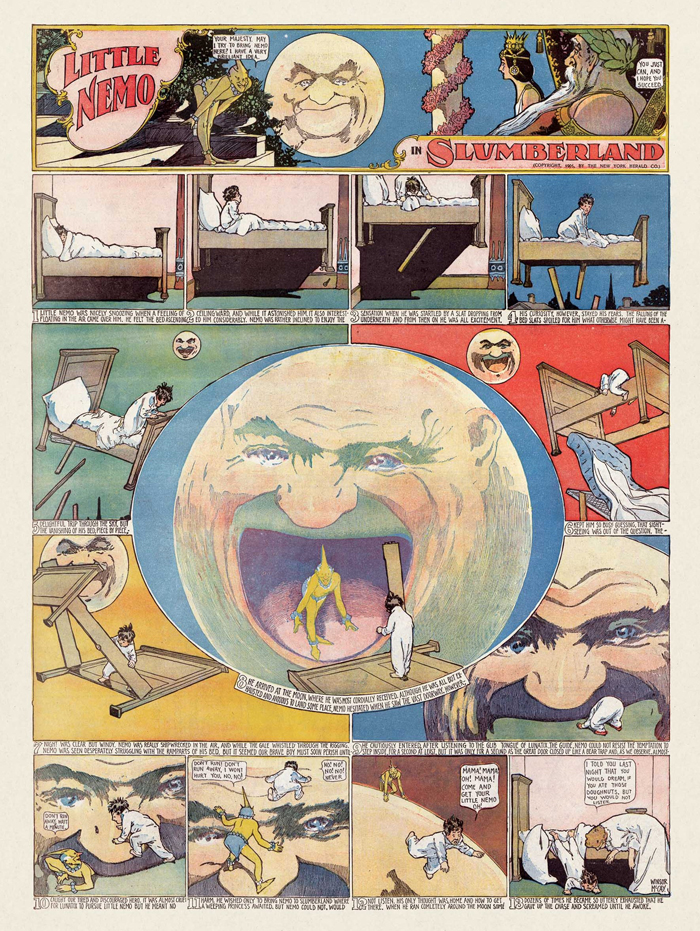

The earliest and greatest works were featured at the Hammer, though — McCay’s Little Nemo In Slumberland, Feininger’s Kin-Der- Kids, Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and Segar’s Popeye — and they eclipsed the rest of the show. In fact, I found one aspect of Masters of American Comics highly unfortunate — the best artists were the first featured in the exhibit! For example, if one saw the show in its intended chronology, McCay came first; his room was simply unbeatable, not only for its ahead-of-its-time psychedelia but also because his work has long been impossible to see.

McCay’s masterpiece, Little Nemo In Slumberland, which ran in the New York Herald from 1905 to 1911, is considered to be among the first examples of the paneled narrative form we have come to call The Comics. McCay experimented with the sizes and shapes of his panels, sometimes elongating them, sometimes stretching them horizontally across the newsprint page, as a way to emulate Nemo’s oneiric state. (The strips took place during Nemo’s sleeping hours, and always ended with his waking up in bed, dazed.) In one panel, for example, the panels grow larger and larger to accommodate Nemo’s metal bed frame, which eventually grows bigger than the skyscrapers it flies by like some magic carpet. In another, panels drawn tall and skinny like the stripes on a circus tent are filled with a circus-like narrative showing Nemo and his buddies distorted in funhouse mirrors. McCay’s room also contained amazingly bizarre panels from Little Nemo in the Palace of Ice and Dreams of A Rarebit Fiend, the prototype for Nemo. (Formatted similarly, in each strip the protagonist, in this case a Rarebit Fiend, falls asleep and has outlandish dream-adventures.) It was inspirational (and a bit tragic) to see how colorful, smart, and entertaining newspaper funnies used to be.

(For further exploration into the world of vintage newspapers, check out The World On Sunday (Bulfinch Press, 2005), a unique look by authors Nicholson Baker and Margaret Brentano into the New York Herald’s great competitor, Pulitzer’s World. The book shows great comics by McCay’s friend and colleague, George McManus.)

The other highlight of the exhibit was the Herriman room. Wall-to-wall Krazy Kat, from its 1913 debut onwards, showed how Herriman took McCay’s sense of experimentation further by adding to innovative panel design formal patterns on the page. These artistic flourishes are distinct from the narratives in which Krazy Kat seeks, in vain, the love of a mouse named Ignatz. (Krazy and Ignatz are Itchy and Scratchy’s ancestors.) One framed strip seemed especially magical. In it, Krazy Kat is Don Quixote (or Kiyoty, in Herriman-speak) and the main panel consists of a giant red sandstone mesa, interrupted by smaller panels showing Krazy Kat and his shamanic animal friends telling stories and pondering the universe. Text running down the left side of the piece reads:

The Clocks of the Universe are Chiming the How of “Now”= and “Joe Stork,” who dwells on the topside of the enchanted mesa, in the desierto pintado = and who pilots princes and paupers, poets and peasants, puppies and pussycats across the river without any other side to the shore of here = is telling Krazy Kat a tale which must never be told, and yet which everyone knows.

No other artist in the exhibit used language in such a stream-of-consciousness way as Herriman, just as no one else innovated the panel structure like McCay. The artists exhibited right after these two had some tough competition!

Masters of American Comics succeeded, to say the least, in its goal to elucidate the “four distinct periods” in the history of American Comics (as defined by John Carlin in the catalogue’s introduction). The 1900s-1920s was a time of unparalleled experimentation with exemplars such as McCay and Herriman. Comics from the 1920s-1940s portrayed both a Norman Rockwell America, as in Frank King’s Gasoline Alley, and Noir, with scenes of violence in Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy reminiscent of the novels of Raymond Chandler. Bound comic books such as Captain America and MAD emerged between the 1940s-1960s. The fourth period, still ongoing, started in the 1960s with the rise of independent comics.

To see the beginnings of the genre in comparison to what has happened in the past thirty years was, to me, the most relevant politically. Starting in the ‘60s, continuing through the Vietnam War-era counterculture, and into Punk, the main function of comic art has been to provide an outlet for humorous, outrageous, cheeky, or even offensive (see Mike Diana’s awesome Boiled Angel strips) political commentary. Similarly, McCay’s work was politically based in Social Realism. As Richard Marschall points out in his book The Complete Little Nemo in Slumberland, some fans read Nemo’s “response to squalid conditions — magically transforming tenements into temples, for instance, and healing the lame…as gently offering a fantastic escape from daily horrors.” McCay did bookend his career as a comics page artist with the making of political cartoons, and many fine examples were in this exhibit. McCay’s art, as much as the druggy fantasy comics of today’s newest comic artist crop like Paperrad and Fort Thunder, combats urban crises and problems with modern industrial life with alluringly escapist plots and settings. In the scope of the exhibit, Schulz’s Peanuts strips were, of course, fun and lovely, but they weren’t testimonials to the transformative powers of art in the same way McCay’s strips were.

Nevertheless, this show offered a rare opportunity to witness the evolution of the comic book as we know it and looking at the exhibit through that critical lens, Masters of American Comics has already become an instant classic.

Trinie Dalton lives in Echo Park. Her two books are Wide Eyed (Akashic), a short story collection, and Dear New Girl or Whatever Your Name Is (McSweeney’s), an art book based on students’ notes she confiscated as a high school teacher.