Make Me Feel Mighty Real: Drag/Tech and the Queer Avatar, installation view, Honor Fraser, Los Angeles, March 3–May 27, 2023. Courtesy of Honor Fraser. Photo: Jeff McLane.

A flash summer storm overtook the Bowery. But refuge was at hand. We ducked into Howl! Arts/Howl! Archive, which was exhibiting Brian Butterick {Hattie Hathaway} And All They Loved. Hattie was the drag persona of Brian Butterick, who, from the late 1970s into the early 2000s, moved through a cat’s lives of downtown venerations: co-founder of the performance party Jackie 60, at the Meat Packing District club Mother; creative director at the East Village proto-club-kid mecca, The Pyramid Club; co-founder of Night of 1,000 Stevies; bandmate with (and paramour to) David Wojnarowicz in 3 Teens Kill 4; and member of the Blacklips Performance Cult, recently eulogized in a catalog and LP by co-founders ANOHNI and Marti Beaut. Butterick passed away at the beginning of 2019, and life-sized cut-outs from her memorial, both in and out of drag, loomed uncannily within the space. My companion was the long-time Bowery dweller, artist, curator, and burlesque historian Scott Ewalt. Soon, we were pleasantly surprised to be joined by superstar DJ Honey Dijon. There began an intimate, insider walk-through with some of the quickest minds (and tongues) in this particular underground. Honey had recently acquired some pieces that Ewalt co-curated, with Jamison Edgar, into the exhibition Make Me Feel Mighty Real: Drag/Tech and the Queer Avatar, staged at the Los Angeles gallery Honor Fraser earlier this year. And so, before our stroll began, a bit of tea needed to be spilt.

Tea is a form of drag divulgence, typically relegated to speech and not fit for print. However, considering that this online review concerns the dance of drag and trans lives from the streets to the white cube, forgive me a touch of flagrancy, for that gossip wove a context that proved more than meaty enough to untuck here. Press notes for Make Me Feel Mighty Real muse upon the concept of technology as it applies to historical drag performance, online fantasy ideation and gender-bending play. Pushing this concept further, the curators propose that drag is a technology, one of transformation and world making. But in the Howl! office space, Ewalt purred to us the real story that inspired all this exploration: the Scottish gallerist saw her teenage son gaming as a buxom and bodacious female-presenting avatar. When she inquired as to why he had selected this female multiple for his online play, he retorted with the pugnaciousness of a teenager: “It’s not a woman, mom! It’s a drag queen. Besides, all my friends do it. We’re normcore in life and drag queens online!”

Fraser’s resulting confusion led her to reach out to Ewalt, to see if that perplex could a good show make. Drag is an action, an ethos, an aesthetics, and a discursive space (hence my spilling of tea). It can be and typically is a minoritarian lens applied to popular objects that create fissures or cleave space that otherness might occupy. It is funny, critical, and lends itself to parody. When it comes to science, drag has come into conflict with contemporary biological nomenclature in pivotal public spats (can trans people be drag queens?), although the drag stage is often the first step for such explorations of identity. I wondered too, with my allegiance to the humanities and ignorance of science, how drag could possibly be engaged as tech-play.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines technology as “the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry.” I can actually think of no better example than the viral video, “Best Drag Queen Entrance EVER!,” which was filmed at the 2001 Miss Gay Black America Pageant and is represented in Make Me Feel Mighty Real on an iPad.1 In the performance document, Tandi Iman Dupree drops ten feet from the rafters into a splits or “death drop” on stage, dressed like Wonder Woman, to the accompaniment of the Bonnie Tyler track “Holding Out for a Hero.” Her dance partner is Superman. Dupree brings together the physical rigor of her gymnastic feats and the artisanal paint that good drag mimicry commands in an industry born underground (this was a decade before the mainstream explosion brought on by RuPaul’s Drag Race). The performance pushes virtuosity through a sissified lens so totally that you can’t help but throw your bills. Also on offer is the wry humor of this uncanny camping and, for a popular culture that still lacked diversity in its superhero(ine) casting, a racial critique.

Tom Rubnitz, Pickle Surprise, 1989. Video still. Single channel-video. © Tom Rubnitz. Courtesy of Video Data Bank, School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Elsewhere in this room at Honor Fraser, which traces historical drag approaches from female mimic magazines to Wigstock festival posters (print technology!), RuPaul appears in her originary, communal context, not running the show but mugging with her sisters in the internet-famous Pickle Surprise (1989) by Tom Rubnitz.2 Rubnitz acquired one of the first consumer-grade video camcorders in the early 1980s, way before social media, and the resulting body of work hums dizzyingly between eager drag performances for the camera and the giddy nightlife antics of queens just thrilled to be along for the ride. In this section of the exhibition, a keen and cloying relationship to media and materiality explodes across bustling vitrines, salon-style photography, and the exemplary tools of the trade, such as the elaborately styled wigs of drag queen Perfidia. The posters, flyers, and magazines are at once practical and tactical, as they spin queer worlds out of printmaking, wig-weaving, and even pissing. Andy Warhol is a natural here, and the Ladies and Gentlemen series (1975), which applies his famous print approaches to divas of a different fame game, is a welcomed go-to for any exhibition focused on the drag arts. But the curators’ decision to include the Oxidation Paintings (1977–78) is smart, probing, and randy, even. These copper-painted wall works are alchemical in their causal production (Warhol directed male visitors to the Factory to urinate on them). Yet the absent penis of their making haunts the finished product as it does this room, where it’s echoed by the myriad drag queens and trans women hoodwinking out from their photographic documents.

Tom Rubnitz, Pickle Surprise, 1989. Video still. Single channel-video. © Tom Rubnitz. Courtesy of Video Data Bank, School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

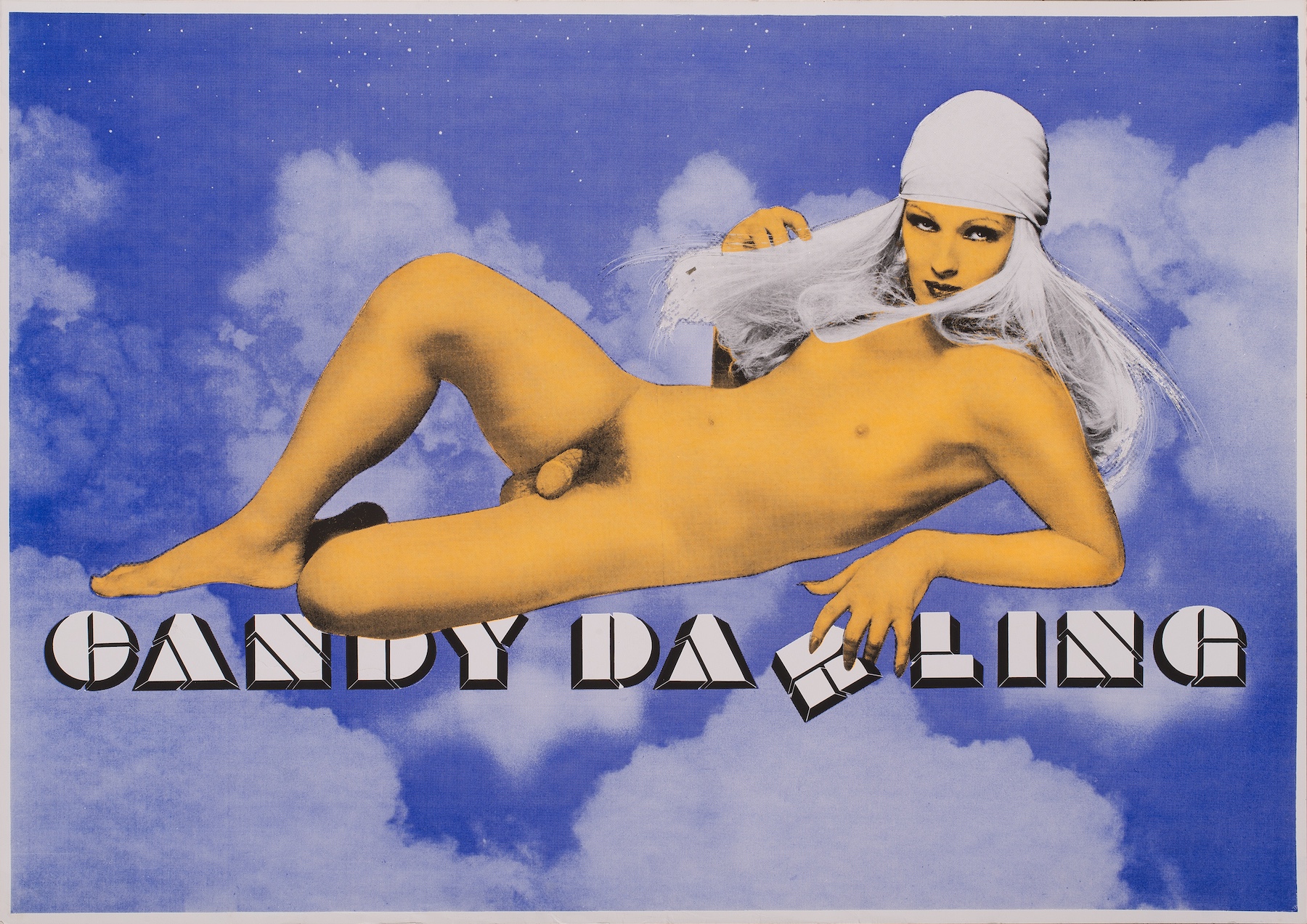

This candy tension adds a charge to the roster of queens represented in the exhibition, which includes many that you would hope to see and live for: Divine, Sylvester, the Cockettes, Candy Darling, Jayne County, Joey Arias, Lady Bunny, Leigh Bowery, and Greer Lankton, who give way to the following generation of queendom, such as Octavia St. Laurent, Mona Foot, ANOHNI, Miss Guy, and International Chrysis. Candy plays the foil in a remarkable dayglo lithograph by Interview Magazine illustrator Richard Bernstein. The trans icon’s nude body is printed in vibrant orange against a cloudy blue sky. Her penis tilts limply towards the viewer, as her eyes glower outward. It’s a defiant, radiant glare—her eyes paper white against the golden glow of her body. It’s also an image of zeal and joy. A fabulous painting of Aretha Franklin by the drag queen Tabboo! bursts with color and the kind of ecstatic gestural energy that fandom conjures. In a deftly drag move, this is Aretha as Tabboo! sees her, proving that drag is a verb—as in world making—and not tied exclusively to the transformation of self. Such joy can come from self-love and diva worship but also contains multitudes (lest we forget the shady pleasure that queens incur at others’ expense). With such threats in mind, Warhol’s absent penis can become the drag version of psychoanalytic lack, the cunty barb that anxious spectators at a drag show are always keen to thwart as the queen looms in. Looking about the room, there’s as much dare as celebration. To paraphrase the Kylie song, it’s in their eyes.

Richard Bernstein, Candy Darling, 1969. Offset lithograph in colors on wove paper, 23 x 32.5 in. © The Estate of Richard Bernstein.

This room courses with intoxicating tension between document and persona: Who is the world maker? Is it the performer, who ostensibly commissioned the attire, beat the mug, and directs the look? Is it the person who is credited as the creator of the work on the checklist? And what part do those craft objects play as they impart this transfiguration? So much of the imagistic power of these artworks lies in the transformation and performance of identity that they immortalize, especially considering that so many of these artists and performers are no longer with us. “I never dreamt that I would get to be the creature that I always meant to be,” the Pet Shop Boys eulogized in their AIDS anthem, Being Boring, “but I thought in spite of dreams you’d be sitting here with me.” In a room stacked with mugs, I gravitated toward the contemporary, glittering assemblages by Max Colby, which I instinctively intuited as portraits. These vibrantly colored wall works are all called “shrouds,” dated 2022. They clutter together the junk of drag life. “Fabric, flowers, garland, costume jewelry, buttons, plastic flowers, beads, sequins, thread, fabric, pine,” reads the checklist. In this room, their abstraction becomes ceremonial. Colby’s ritual objects proffer that such fabulous lives are an assemblage of (and ascension from) all of this trash. These bedazzled collages are personal portraits, configuring afterlives for the ancestry that they usher over.

In the remaining three rooms, which are filled with more contemporary output largely displayed on flat screens and through projected imagery, in tromps the internet—and drag morphs into a cyber-blur of cultural referents. This has always been a quality of the culture, but here a real tech patina sets in. Glam is gone for gleam (or glean). The darkened south gallery is dominated by a multichannel projection by House of Avalon, best known for their members Symone and Gigi Goode, contestants on RuPaul’s Drag Race. Intricate 3D models of their apartments, festooned with Madonna and RuPaul posters, wigs, and other fab detritus, spin like small worlds, crudely rendered to appear like a children’s book illustration of Pee-wee’s Playhouse. On the opposite wall pulses a computer rendering of a brain, inside of which plays trashy, cult scenes from the 1990s, moments that constructed a nascent queer imaginary, including Lexi Featherston’s death in “Splat!” an episode of Sex and the City and footage of Anna Nicole Smith and Rosie O’Donnell all mashed-up with Barbie ads and The Wizard of Oz. After gorging on all of these layers of consumption and projection in one room, the viewer’s body becomes the threshold between this mental overload of camp and its physical manifestation in sugary (but humble) domestic interiors.

Make Me Feel Mighty Real: Drag/Tech and the Queer Avatar, installation view, Honor Fraser, Los Angeles, March 3–May 27, 2023. Courtesy of Honor Fraser. Photo: Jeff McLane.

In her text, “Dungeon Intimacies,” trans theorist Susan Stryker writes, “I envision my body as a meeting point, a node, where external lines of force and social determination thicken into meat and circulate as movement back into the world. So much that constitutes me I did not choose, but, now constituted, I feel myself to be in a place of agency.”3 Stryker’s essay questions how the ebbing histories of the outside world and the actions that ricochet through it write the trans body. Eva Hayward follows suit in her essay “Spider city sex.” First pondering how the immediate qualities of city life (concrete, stench, neon, threat) become part of the body, she pivots to celebrate trans-speciation, how animal genomes and animal testing have always been a part of trans life, and the surgical evolutions that construct it. She writes, “Changing sex, then, is also always about changing senses and species in the flesh.”4 The deeper one moves into the contemporary artworks included in Make Me Feel Mighty Real the more Hayward’s polemic resounds. Science fiction and the queer(ed) avatar are conjured in Antigoni Tsagkaropoulou’s Dentata Pearls (2021), a queer VFX fantasia, where bodies explode into technicolor creatures. The embodied sense of that science fiction is made all the more palpable by the inclusion of the various costume pieces used to make Dentata Pearls, which are displayed in the exhibition alongside the video. Forgive my need for a tether, but the gamer scene’s lack of indexicality has always thwarted my total immersion. These horned glove-claw-hooves, crafted in synthetic, primary-colored vinyl, give me that life. More exciting still are the motion capture avatars created by Huntrezz Janos, whose worlding brings to mind the Sun Ra vehicle Space is the Place (1974) by way of Reboot (1994). Here, the body is no longer finite but rather rendered as an astral bleed into the VR realm through live motion capture. The dazzlingly ornate quality of the artist’s digital renderings is matched by her own fleshy embrace of those virtual lqqks, going so far as to purchase jumping stilts to bridge the gap between ideation and manifestation.

This brings us back to the goss that gave way to the exhibition (and this resulting response). The desire to play drag while gaming signals the explorative ethos of contemporary youth culture and their permissive attitudes towards queerness. The kids are alright—at least as far as gender is concerned. But the real teeth in this show emerge from material productivity, in the tangible, beyond the gaming console and outside of the entertainment room. For many, drag is real life—painful, joyous, and still taboo.

Scott Ewalt, Wigstock 1997, 1997. Digital image, 18 x 24 in. © and courtesy of the artist.

As the rain began to die down on our stormy Howl! sojourn, Ewalt and I gagged over the illustrated layout for the Pyramid Club programming calendar for September 1987 in the Brian Butterick {Hattie Hathaway} exhibition. All of the design was done by hand in pen and collage on paper. Under Plexiglass, the flyer mock up brimmed with drag heavyweights: Lypsinka, John Sex, Alexis del Lago, International Chrysis, Kembra Pfahler, Lady Bunny, Wigstock, Dean Johnson, Frieda the Dancing Disco Doll. And this was just one month! At stake for this set was more than play. Oh, they played alright. And hard. But the resonant tech laid bare in Make Me Feel Mighty Real is the zeal of industry. Industry need not be a capitalist construct. As Hattie taught us that day at Howl! (as she had for five decades prior), industry can be another word for community. Industry means refuge, survival. And this mighty, real community was forged from sweat, tears, and wig glue, in billowing flesh and blood. x

Bradford Nordeen is a writer, curator, and the founder of Dirty Looks Inc. He has written for Frieze, Art in America, Afterimage, and Butt Magazine; and was a 2018 recipient of the Creative Capital / Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. His publications include Because Horror (with Johnny Ray Huston), Check Your Vernacular, the Dirty Looks Volume series (editor), and the forthcoming novel Blessed Western. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Film and Digital Media at University of California, Santa Cruz.