Following is an excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book, Concrete Comedy: An Alternative History of Twentieth- Century Comedy.

“There are already enough first-class painters. Martin Kippenberger only wants to be the best second-class painter.” — Burkhard Riemschneider

A society that reduces the human experience to two poles, Winning and Losing, proceeds from the assumption that each individual, by his or her own efforts, succeeds or fails. The “sink or swim” credo of the free-market state is founded on a tiresome assumption, however. To win, mustn’t one know how to win? And doesn’t acquiring that knowledge — knowing what winning feels like, why that might be a desirable feeling, the effort demanded to secure it — require, somewhere along the line, personal contact with an experience of winning? One of the purposes of children’s games, for instance, is to expose kids to artificial situations that carry the potential for early, formative contact with winning. Games are designed not just to get kids used to being around each other but to spark very particular sorts of ambitions in enough of them to, eventually, when their turn comes, Keep Society Operating. Subtle and ingenious this training system may be but it has one important drawback: it doesn’t work for everyone. Many children simply don’t acquire personal experience with winning. The reasons vary. Some will be thwarted by circumstance; some will lack ability within the only theaters that the adults around them will think to offer; in others the instinct to win will be, inexplicably and through no fault of their own, absent. More profoundly, a certain percentage of kids will find the basic set-up—the Game itself, with its orientation toward competition, points and goals, training and trophies — seriously wanting; for them, games of any kind will be, literally, a waste of time. Of those who actually do win, some will find the experience, at least as far as they’re concerned, devoid of satisfaction — i.e. “hollow.”

The truth of the matter, then, is that some people in fact don’t learn how to win. While there’s no shame in this, try telling that to anyone who hasn’t made contact with the experience of winning. Each faces a difficult self-appraisal. For if not a winner then…you must be a loser, right? Possibly, yes — but (as the above histories indicate) not necessarily. For the non-winner, this “not necessarily”— this complication— becomes, in place of Winning, the formative experience. A person formed by this complication will be inclined to regard Winning as nothing more significant than a system of values which has been agreed upon by enough people (or, equally effective, by a smaller number of people with enough power) to impose their agreement on everybody else. A person formed by this complication will view with detachment the system of values on which Winning depends and of which it is its expression. That person will perceive Winning not as a goal but as a mere component in a theater.

At that point things get interesting. That person might decide to explore his sense of detachment. He might opt to foreground his complicated relationship with success. If he emphasizes it furiously or cannily enough that person might succeed in establishing himself as a symbol of a complicated relation to success and, in that way, universalize his situation.

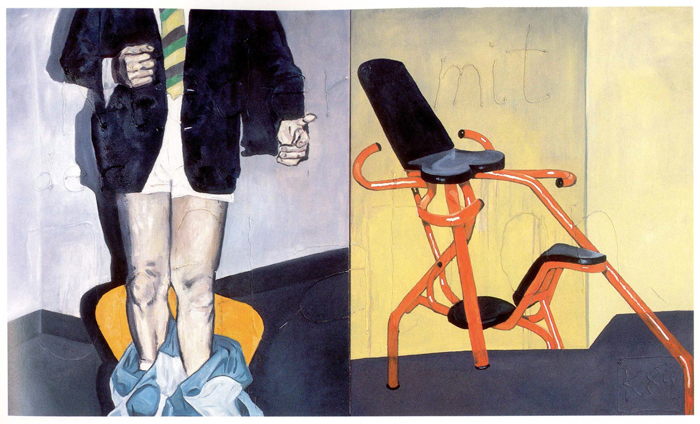

Martin Kippenberger, Broken Child, 1985. 130 x 120 cm. Dispersion, rubber, stickers on canvas.

Admirable as it may be, successfully establishing oneself as a symbol of a complicated relation to success does not entirely override the comic symbol’s sense that he or she is dwelling inside a joke situation. To dwell inside the joke situation is to perceive everything through the prism of the joke situation. Everything exterior to it will seem “a joke,” i.e. something designed to serve, maintain, or extend the system that values Winning. Any thing that forms, maintains, reinforces or extends such a system cannot be taken seriously. Only the condition of being in the joke situation is to be taken seriously. This is because those who have been condemned to live inside the joke situation rightly understand their sentence to be a serious thing. They intuit—rightly—that only an experience as powerful as the formative experience of Not-winning can free them, and the chances of that diminish with each passing year’s march deeper into the forest of adulthood. They’re already formed.

The joke situation is itself a system of sorts, of course. This is an irony. One of the discoveries of our time is that irony expands. Due to the expansive nature of irony, establishing oneself as a symbol of a complicated relation to success is no guarantee of release from the joke condition. Martin Kippenberger seems to have grasped the situation at a very young age. Based on the evidence—i.e. the finesse with which he manipulated his own symbolic relation to questions of success and of failure—it appears that he’d had plenty of time to get used to the exquisite torture of living inside the joke situation; time to get used to the idea that coming in second is better comedy than coming in first; time to become comfortable with the dimension of sacrifice attendant upon his own symbolic condition. He’d had time, in other words, to set up shop inside the joke condition.

Martin Kippenberger, Down with Inflation, 1984. 160 x 266 cm. Mixed media on canvas.

Can anyone say with certainty that Kippenberger’s transformation into this sort of comic symbol began on the day that his Essen, Germany, elementary school teacher awarded him a second-place prize in art? In his own mind the little boy must have been convinced that he’d deserved first prize, because his disappointment at not receiving it had the weight and scale of real injury: thereafter, young Martin skipped the art class. There are limits to the usefulness of unlicensed psychoanalytic speculation about a specific incident’s exact significance to anyone’s psychology. We know only that an unmistakable disillusionment pulses through all of the man’s work. His massive oeuvre of drawings, paintings, sculpture, multiples, photographs, books, posters, and recordings reeks of smart-aleck provocation, strategic insult, calculated messiness, exquisite error, self-aggrandizing self-pity, and the swaggering inventiveness of the genuinely gifted: Kippenberger was an extraordinary draughtsman and highly original colorist.

Identity formation isn’t limited only to the events of an individual’s private biography, of course; collective experience contributes its own special touch. Martin Kippenberger was a German, and in a span of just thirty years Germany, twice demonstrating a capacity for pursuing bad ideas to calamitous ends, had lost two world wars. Judging strictly from the evidence of history anyone would be justified in concluding that, in the nation-state sweepstakes, Germany should be assigned to the “loser” category. At any rate, Kippenberger, born in Dortmund in 1953, a child of the generation directly affected by the more recent war, inherited a situation already painfully athrob with complication, confusion, and self-doubt. Mama and Papa had participated in the war! Were they guilty of anything? If so, how guilty? And guilty of what, exactly? Being German?! And what relation to war guilt did innocent baby Martin have? As his own generation matured, what model of national identity were they to draw upon — the post-war identity (which in its Marshall Plan, pulling-itself-up-by-its-bootstraps way directly referred to the tragedy and thus to pervasive, corrosive guilt) or some other fantasy identity that didn’t yet exist but which the nation sorely needed? The problem of postwar, peacetime Germany was, most emphatically, a problem of the model.

Such thoughts and anxieties were by no means the private reserve of young Kippenberger; they would have been alive in the mind of any German in the years after the war. It’s Martin Kippenberger, though, who intuited that the comedy of values to which he was already attuned for other, deeply personal, finally unknowable reasons, echoed across the entirety of postwar German society. A man of his time and place, he resonated as an especially compelling symbol in Germany because of that country’s own confused legacy of success and failure, of winning and losing.

An aggressive, willful complication of values thus fermented inside him. Courageously throwing himself headlong into that complication, Kippenberger would become postwar Germany’s most influential comic figure.

Ironically, he settled on the art system — the special bubble-world of galleries and museums, curators and collectors—as his base of operations, and as might be expected, his relation to it was complex. A context that canonizes a slate of classic “winning” values — beauty, refinement, taste, prestige, uplift — art provided him a permanent, sturdy, and yet (art being an abstract human pursuit) finally elusive target for his rebellion. At the same time, his immersion in that system continually charged the battery of his private joke-condition. It reinforced its masochistic component. (He was well aware that it did. The image of a crucified frog appeared in more than one of his works.)

And yet Kippenberger’s public persona wasn’t only a juvenile “acting out” stemming from some deep personal need that’s finally none of our business; it also drew power from a more objective condition, one intrinsic to art.

Martin Kippenberger, Street Lamp for Drunks, 1988. 280 x 40 x 40 cm. Steel, glass. Photo: Nic Tenwiggenhorn, Carmona-Sevilla.

As a human activity lacking a priori worth, art is genetically uncertain and volatile (a truth reflected, vulgarly, in the marketplace: careers ebb and flow, the jury can be “out” during an artist’s entire lifetime, artists who are crucial to one generation mean nothing to the next whilst the stock of other, neglected artists climbs…). Arrangements of forms, arrangements of color—meaning ebbs and flows in them without ever attaining stability; art permanently teeters on the brink of meaninglessness. Ironically, this very wobbliness is one of the endeavor’s chief virtues; art doesn’t only institutionalize the incontrovertible condition attained by historical evidence but, as well, the perfect unpredictability of imaginations yet unborn. It was one of the contributions of modern art to recognize this fierce duality and make it part of the artist’s arsenal. The stratum of modern art known as the “avant garde” is defined in part by the desire of certain artists to intensify questions about the determination of meaning and to deploy them in an effort to destabilize the status quo included in their inheritance. Kippenberger was of this tribe. He applied art’s natural uncertainty strategically, using it as a battering ram in a gradual, cumulative, persistent assault on the question of valuation — on, in other words, the very idea of coming in first. There was an element of revenge in his ambition, to be sure, but revenge is a complex affair. Cruel toward art his comedy may have been but it was exceedingly generous to humans.

In contrast to the likes of Piero Manzoni, Jeffrey Vallance, or Bruce Nauman, three examples of comic imaginations who favor highly specific and exact gestures freighted with existential weight, Kippenberger adopted an all-over, “field” approach. There’s a sloppy, carnival atmosphere to his output, with multiple rings of activity. Although he did have a consistent style (the oil paintings were usually made by hand painting collaged, distorted images or image-fragments onto messy, painterly grounds, while the sculptures—dryer, ramshackle affairs, frequently of wood or metal—favored forms that suggested hybrids of furniture and architecture) consistency as such, whether of materials, forms, or “look,” was neither his point nor his aim. He did whatever occurred to him, got the thing made any way that he could. Some of the pieces were handmade, others made by assistants, still others jobbed out and fabricated by contract. With Kippenberger, it was always “anything goes,” and all of it was equally consequent. Which also is to say that each individual object was equally inconsequent; whereas Manzoni’s, Vallance’s, Nauman’s things give the sense that they couldn’t have been done any other way than this way, Kippenberger’s creations convey a sense that they might have been done almost any way at all. Existential specificity gave way to from throttle production.

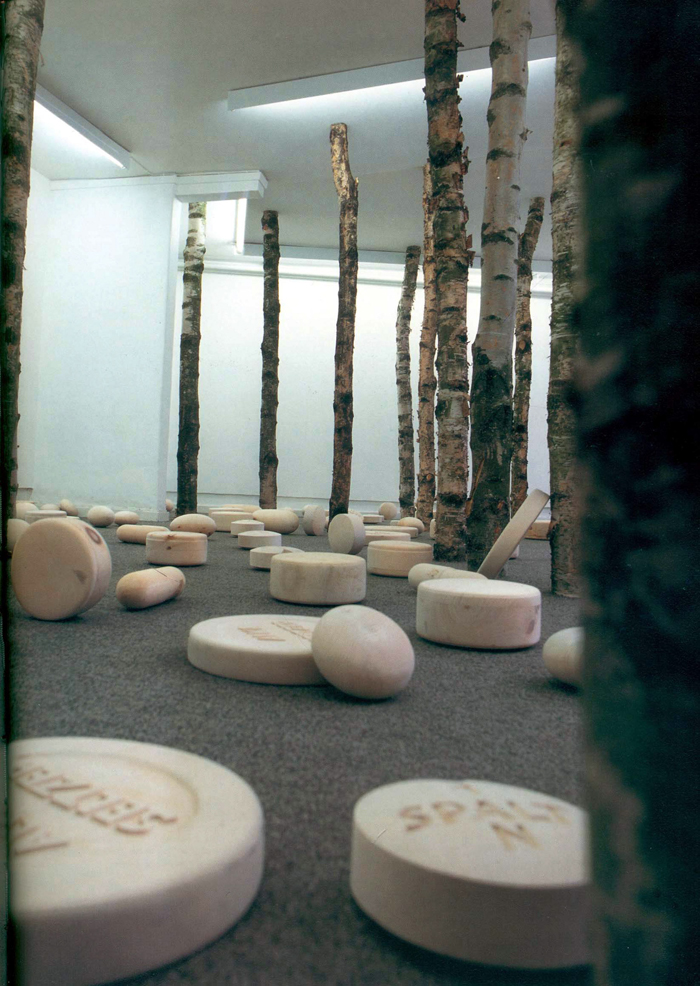

Martin Kippenberger, “I am going into the birch forest as my pills will be taking effect soon,” 1990. Installation consisting of 20 birch trunks and 111 wooden pills. Installed at Anders Tornberg Gallery, Lund, Sweden.

“Anything goes” isn’t meant to indicate that Kippenberger’s production model was perfect; his all-over, “field” approach occasionally led him to disperse his energy over too wide an area, resulting in creations that, for all their material inventiveness and visual flash, felt hermetic, arbitrary, or half-baked. Yet these imperfections didn’t really matter, since what he was after isn’t contained within the limits of the picture frame or embodied in a sculpture anyway. Like all comdedians, his sensibility was essentially theatrical. Indeed, in early adulthood Kippenberger, who at the time bore a passing resemblance to the movie actor Helmut Berger, had briefly entertained the idea of pursuing an acting career. The role of “professional contemporary artist” better suited, for it allowed him to be author as well as performer. And, of course, being an artist had the notable advantage of playing out in real materials, real space, real time…. His entire production is thus to be considered as a prop, in a theater starring the one and only Martin Kippenberger, the globe-trotting, continually-improvised performance of which enjoyed a twenty-year run prior to its lead’s death, from liver cancer, in 1997, at the age of forty-four.

Kippenberger didn’t just make pictures and objects, then, he played the guy who made them. Just as the working actor must find ways to keep himself before the public, so did Kippenberger’s performance similarly depend on commanding the art public’s attention. Fortunately, he understood that his part in the theater of the art system didn’t have to be confined to what he made in the studio, or to paint, wood, and sculptmetal. The successful artist has other tools at his disposal. Exhibitions, advertisements, announcement cards, catalogues, interviews, the art opening, the dinner after the art opening, the morning after the dinner after the art opening, the story about the morning after the dinner after the art opening…. —Kippenberger treated all of these as points of contact between performer and audience. Immersing himself in the official rituals of production, distribution, exhibition, and reception by which the art system is manifested, via one hundred fifty solo exhibitions, thousands of objects, a few dozen artist’s books, and scores of exhibition posters, he managed to stay almost continually on stage, and in the public eye.

Thus to a conceptual foundation laid just a short decade before by the Belgian Marcel Broodthaers—the idea that the rituals of the art system comprise a theater—the young German added a thick frosting of personality. One of the great mysteries of life, what we call “personality” is constant and at the same time elusive, a force of nature that isn’t manifested with equal force in all. Some have too little of it, some “too much.” Kippenberger’s own compelling, demanding, entertaining personality, the angles and volumes of which were determined by life inside the joke situation, became the “logic” unifying all his output, a glue holding together not just his hyper-varied output but also the casually outrageous extra-curriculars that added, with high theatrical self- consciousness, to his legend: the incessant traveling, the public drunkenness, the standing on chairs in restaurants and singing, the funny-dance inventing, the curating and collecting of other artist’s work, the founding of museums on tiny Greek islands, the conspiring to establish artists’ lodges (with just three members the Lord Jim Lodge — its motto, “Keiner Hilft Keinem, in English “No One Helps Nobody,” signals the psychology of the brutally competitive German art world — was surely the world’s most exclusive)…. Apart from Warhol, has any artist posed as frequently for another’s camera or been as frequently interviewed?

Kippenberger, like Warhol, was in the myth business. When in 1984 he hired a writer to relate his supposed activities and experiences in an haute bourgeois Belgian beach town, the result, The Way It Really Was: Example Knokke suggests a tell-all. But the book, whose cover echoes the design of a line of paperback classics published for use in academic institutions, casually mixes fact and fabrication; “The Way It Really Was…” wasn’t the way it really was. It didn’t matter; authenticity is the concern of journalists, and Kippenberger was in another line of work. “Accommodator Leader Longtime Painter Show-off Over-reacher Performer Deliverer” are the self-descriptions listed on one of his posters. (“Wastrel, host, self-portrayer, …ringleader and go-between…” a newspaper later added.)1 Kippenberger’s pictures and objects are always more than just funny, then; they’re indicators of a human being living in a joke situation. He scaled up the joke to life’s weight and mass.

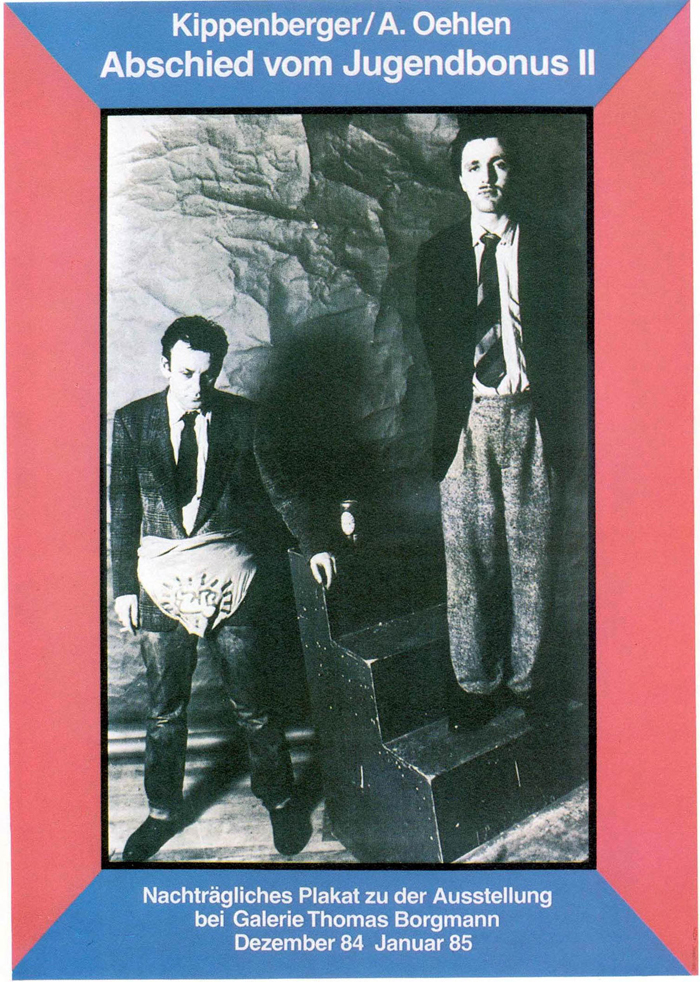

Martin Kippenberger, Farewell from Yought Bonus II, 1984. Exhibition poster, Galerie Thomas Borgmann.

It needs to be mentioned that his approach didn’t go down particularly well with the art establishment during his lifetime. Kippenberger’s work sold, but to adventurous private collectors, not museums. (Now that he’s dead, of course, institutional support has come swooping in.) This isn’t especially surprising, as the art establishment prefers its iconicity neat, neutral, self-sufficient, and separable from an artist’s personal story. Within that context, persona, a theatrical construct centered in people rather than things, has always read as foreign matter, an irritant, a distraction from what visual art is “really about”; persona directly violates the neutrality of form that art celebrates. In making it the organizing principle of his output Kippenberger thus guaranteed himself that 1st Prize would always elude him. Which, of course, is exactly the way that any self-respecting comic figure really wants it. Kippenberger was hardly the sorry victim of a deck hopelessly stacked against him, since emphasizing persona in a context disposed only to tolerate it ensured the distance in which the Non-winner recognizes himself, and on which he thrives. As painful as it must be to perceive oneself as living inside a joke, the right to decide the type and degree of that pain remains the joker’s. It’s what compensation is offered.

In other words, while the situation may have been tragic it was also hilarious. These were matters of life and art merely, not life and death. Moreover Kippenberger, who was more than capable of taking care of himself, gave as good as he got. If the independent artistic imagination ranks near the top of the list of World’s Most Gratuitous Occupations—lacking any real need or justification (without art, the world would still turn, and nicely), the existential actor referred to as the modern artist is always obliged to force his way into the world, insist upon his place, and hold on tight—Kippenberger shoved that sheer gratuitousness into the audience’s face like a cream pie. Emerging in the ‘80s, he presented a German high art version of the ‘70s punk scene in which he’d been schooled. Never directly thematized in the work itself, punk’s skepticism was stained deeply into his attitude. Art might be a noble endeavor, sure, but to assume its nobility was to give off (to quote J.D. Salinger on another topic) “a pious little stink.” Kippenberger preferred to fart. “You really can’t bring about anything new with art,” he said. “I knew that already as a child. One can try to change the world for oneself, but exhibitions are actually, quite superfluous. If one didn’t have to feed a family….”2 He would be indulged in well over a hundred solo shows of his paintings, drawings, and sculptures yet dismiss the exhibition format as “a running gag for the artist. No more.” To the genuine clown punk, a career will be something to put up with. When in Rome: Kippenberger costumed himself for the role not in black leather but in tailored suits.

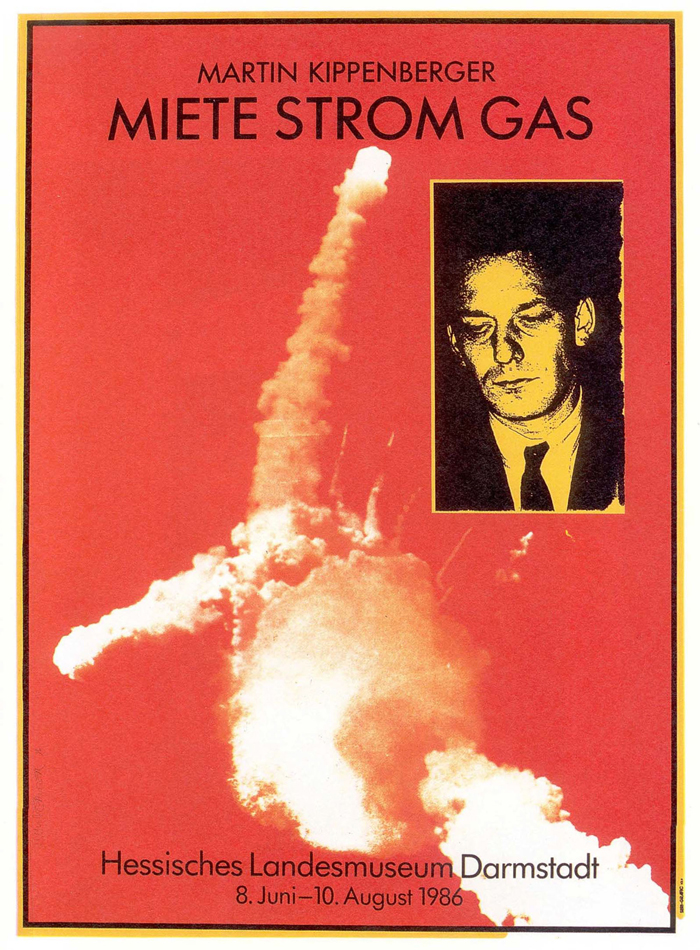

Martin Kippenberger, Exihibition poster for “Rent, Electricity, Gas,” 1986. Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt.

His skepticism was not ill-founded. The sometimes noble, essentially idealistic endeavor of artistic creation had always played out in an all-too-human context, and during the 1980s, the decade of Kippenberger’s emergence, that context had expanded to global proportions. The theater of rituals comprising the art context was understood and accepted by ever increasing numbers of people. What some of the new players had discovered was that their theater could be wedded to and manipulated toward ambitions as old as art itself — wealth, power, and fame. A flood of cash from newly moneyed private collectors floated an elite of artists, dealers, and curators who lived a glamorous international life of constant travel, bohemian freedom, media attention, and privilege. The machinery of art had been scaled up. Techniques for stabilizing the market were being discovered and established. Avant-garde artists began to expect middle-class incomes annually. Clown punk Kippenberger perceived that a context that had been sufficiently systematized to enable anyone to think in terms of having a career as a “professional contemporary artist” was, had to be, something of a racket. One might become an art star within such a system, sure, but what exactly did stardom within a racket amount to? Well, more comedy, for one thing.

Was there a better way to confound the high regard in which art is held than by making deliberately “bad” oil paintings? Painting is perennially the gold standard in fine art. (Books are written and movies made about painters, not video artists!) During the 1980s, the decade of Kippenberger’s emergence on the international scene, ideas about “bad painting” found adherents on both sides of the Atlantic. The sort of intentionally awkward canvases offered up by American artists like Jedd Garrett or Julian Schnabel and Germans like Kippenberger and his frequent co-conspirator Albert Oehlen were influenced by the still fresh and influential punk aesthetic’s embrace of those aspects of life that evade redemption by bourgeois standards of taste. These and other painters sought non- academic approaches to style and subject matter more rudely vital than the middlebrow preciousness and brittle decorativeness that marked ‘70s painting.

While frequently synonymous, bad taste and kitsch aren’t automatically so; to use “bad taste” as a concept isn’t kitsch, it’s a more conscious and calculated position. To render painting in a deliberately awkward manner, intentionally “stupid” and “ugly,” while combining it with sophisticated ideas, was, therefore, to infuse style with

strategy and to transmute strategy into style. “From the very beginning,” Burkhard Riemschneider writes of Kippenberger, “his pictures punish the viewer’s expectation of pleasure and maintain their adamant stance: I am not beautiful. I’m badly painted on purpose, and yet, I’m there!”3 An important effect of this strategy was to make of “quality” just that: a quality, nothing more and nothing greater. A painting, in the modern era, is at once a bourgeois artifact and an arena of experimentation; to emphasize the “materiality” of quality was to crank up the volume, to headache-inducing levels, on a conflict intrinsic to painting. Kippenberger painted that conflict. Riemschneider: “A picture didn’t need to be authentic or ‘good,’ only strategically correct.” 4

The coordinates of Kippenberger’s joke weren’t scattershot, then, but consistent and specific. A displacement or complication of the notion of quality was central to it. A sister strategy was inflation. Kippi, all energy, replaced the spare, tasteful, some would say stingy existential restraint of a Manzoni with, instead, a perversely generous experiment in overproduction. This was not someone who knew the meaning of the word restraint. With his thousands of objects, Kippenberger consciously floods his own market. The deluge of paintings, drawings, photographs, editions, and sculptures has the effect of devaluing all his production—one thing becoming just as good as another—while simultaneously re-investing all of it with value since he’s consciously engaged inflation as a subtext. As goodness isn’t really his aim, the question isn’t whether it’s a problem that one thing is just as good as another; the formulation becomes, instead, that one thing is as “Kippi” as another. Purposely engaging the problematic of inflation he becomes both a willing victim of his inflationary practices, and the wily victor. His own mythology becomes the standard by which his output is measured; in his hands the existential may have become bloated and nearly unrecognizably distended but it’s existential nonetheless. His is still an innovative life lived in a specific way.

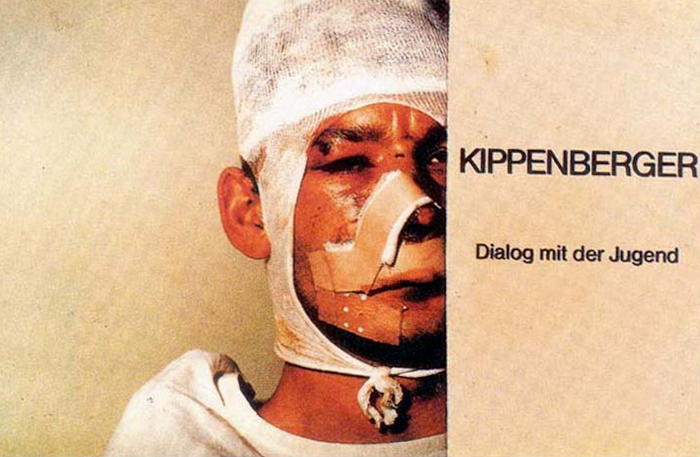

Martin Kippenberger, Dialogue with the Young, 1981. Exhibition announcement card, Achim Kubinsky Gallery, Stuttgart.

While his body of work is always solidly inventive, anyone looking for a “great” Kippenberger — that single work or series that has penetrated deep enough into the history of objects and images to alter the course of that history—will likely be disappointed. There seems to be no work that, in its concept and execution, towers above the others, either in his own oeuvre or those of his competitors. Was that by choice and design? Someone whose identity is so bound up with the Non-winner’s status may not be able to bring himself to produce an obvious winner…. Or perhaps he couldn’t take the context of his operations, with its religion of quality, seriously enough. Of course, that he may actually have lacked the ability to knock the ball out of the park can’t be ruled out either. Is Kippi’s self-designated ambition “not to be the second winner” a confession that he knew himself to be essentially a pastichist, albeit one of superior abilities? If so, the estimation would help to account for the restless search, the manic inventiveness, the constant turnover of ideas….

In fact the question is moot. True, none of the individual works is Great, but they’re all “great” by virtue of the brilliant construct they comprise. Kippenberger— foregoing the existential quality of “this action as opposed to that action,” subordinating his production to his persona through the strategy of inflation, atomizing the performative aspect of comedy across a field that bears his signature — succeeded in transposing himself into a quality. Martin Kippenberger’s great, original creation was himself. To make any of the bits work, the viewer had to buy the premise. A similar logic applies to his comedy. Whether or not any single work happens to communicate anything clearly comic, let alone any clear comedy, it’s comic by virtue of being part of the larger comedy that was The Life of Kippenberger; it’s comic because he was comic. Whether his sloppy slapstick delivered anything as substantial as the specificity it replaced is something of which he is not himself sure. “Please don’t send me home,” the title of one work implores.

It’s in the posters and invitations that Kippi most directly acknowledges the performative construct on which his work relied, and reveals the centrality of his persona to that construct, whilst confirming our view of him as a comic figure. The posters, advertisements, and invitation cards that frame an exhibition and situate the working artist in the public mind are flashcards for complex and private psychological, emotional, and artistic dynamics. As such, they solicit efficiency of expression from even the least disciplined artist. Kippenberger took these paper ephemera as seriously as he took any form of communication; they’re part of his oeuvre, make a contribution to it, and enjoy a distinct character which is largely attributable to the photographic basis of offset printing. Photography’s effortless quotation of reality tempered his over the top, “more is more” aesthetic; temporarily relieved from making everything from scratch, he could relax a bit, and let straightforward depictions of himself in real settings do the communicating. Whereas many artists just stick their name on an announcement card or reproduce an image of one of their new pieces, Kippenberger took the opportunity to picture himself in one or another moment of private theater. We’re supplied glimpses of the charismatic figure familiar to those around him. Here’s Kippi twisting the night away on the dance floor; posing nobly on the beach next to a rusting, beached tanker; looking patient with the entire universe while seated on someone’s snow-dusted public sculpture; hung-over and stunned, in a diaper made from a Keith Haring “radiant baby” t-shirt safety-pinned to the sort of bespoke suit he favored; looking haggard with a cardboard box crowning his big head; joyously naked, in slim hippie youth; sweatily engrossed in intense barroom dialogue…. A motley parade of moods, actions, ideas, jokes, and episodes of self-involved self-reflection, the posters promote his comic gift via those perfect conflations of spontaneous theater (available to any of us) wherein the body becomes a performance vehicle, “reality” the stage, and history the audience.

That Kippenberger may have been a narcissist, always needing to be looked at, doesn’t mean he only flattered himself. If you’re working with the utterly human materials of personality and life-narrative, taking the scenic route to myth isn’t an option. For what heroics the comic figure may lay claim to are attainable only by anti-heroic means—that is, by consistently choosing vulnerability and an unprotected humanness. Life roughs up everyone, but it’s the comic figure that sticks his chin out, and waits. The announcement card for Dialogue with the Young, his 1981 show at Galerie Kubinski in Stuttgart, pictures Kippenberger’s stitched and bandaged face after he’d been attacked with a broken bottle by a woman at S.O. 36, the Berlin nightclub he ran for a while in the ‘70s. Of course, a willingness to look a fool isn’t the same as being a fool; displaying the effects of time and hard living on an elegant, charismatic, handsome man, expressly for his audience’s pleasure, was a recurring theme of the Kippenberger narrative. In a 1988 series of painted self-portraits, for example, he’d juxtaposed his expanding middle-aged physique with party balloons. Evil Dorian Gray hid his decay. Kippi, a good albeit difficult character, advertised it, and in so doing, lent it fragile dignity. Honesty isn’t easy and it isn’t pretty. “Warheit ist arbeit”— “truth is work”—was his knowing credo.

Theodore Gericault, The Raft of the “Medusa”, c. 1818/19. 65 x 83 cm. Oil on canvas. Musee National du Louvre, Paris

In the end, of course, the body disappoints. The balloon sags to earth, the party ends…. We all come in second to death. Toward the end of his own life an ill Kippenberger, pre-empting tragedy, had his wife Elfie Semotan photograph him as, one by one, he recreated the poses of the doomed passengers immortalized by Gericault in The Raft of the “Medusa” (arguably the greatest “dire circumstances” painting). He then—life mimicking a work of art and recycling the mimicry as a fresh work of art—based his own series of lithographs and oil paintings on Semotan’s photographs. In these 1996, works Kippenberger tries to take some of the sting out of his demise and offer us the option to feel something in addition to sadness at his passing. It’s as though the Pompeian dog had decided to arrange itself just so. Kippenberger tossed Gericault’s drifting losers—and himself too—the life preserver of comedy. He couldn’t beat death but he was free to laugh in its face. Granted, it was the second-to-last laugh only, but victory of a kind even so.

David Robbins is an artist and writer living in Milwaukee whose projects include the Ice Cream Social, a now twelve-year-long work most recently manifested at the Musee d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. A volume of his collected essays and interviews, The Velvet Grind, is forthcoming from JRP/Ringier Kunstverlag, Zurich.