Whether in painting or in print, much of Mira Schor’s practice over the last twenty plus years has involved writing. Be it her now classic 1997 text Wet: On Painting, Feminism and Art Culture1 or her word and punctuation paintings dating from the early nineties, Schor’s ongoing use and interrogation of the written word has informed cultural production via a feminist discourse. The exhibition “Mira Schor: Paintings From The Nineties To Now” at CB1 Gallery is the first survey of Schor’s work to be shown in Los Angeles, and it offers a rare look at a practice equally dedicated to its creative and its critical implications. For Schor, meta-signification is an act of resistance, a dogfight of meaning that questions the discursive dimension of the social and the part it plays in the formation of the personal. It’s clear that while being deliciously seductive, these works (and their implications within the wider culture) do not rest easy on the wall.

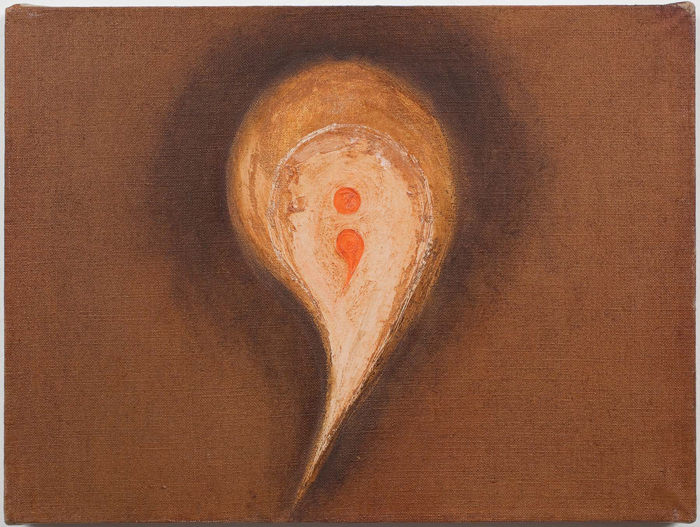

Mira Schor, Semi-colon in a Flesh Comma, 1993. Oil on linen, 12 x 16 in. Courtesy of the artist and CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles.

Beginning with Semi-colon in a Flesh Comma (1993) and moving chronologically through some thirty paintings that end with A Life (2010), CB1’s focused retrospective highlights Schor’s relationship to the language of painting. Her early word and punctuation paintings from the nineties transition to a haunting series of works where the word (and its reference) come to be replaced by thought bubbles in the late oughts. These paintings then set the stage for the exhibition’s final series of figurative works.

In the exhibition’s early works, Flesh (1997), Lack (1997), Trace (2000, 2001, 2004) and Sign (2005), Schor presents trademark terms from French psychoanalytic philosopher Jacques Lacan’s discourse of difference. Within this discourse, Lacan built upon Freud’s template of unconscious drives (in this case with respect to language and the construction of subjectivity) and in doing so, afforded early seventies feminism a working model from which to describe, represent, and in turn resist the machinations of patriarchal oppression. It’s with this resistance in mind that Schor brings Lacan to the conversation. Given painting’s conspicuous history with respect to gender and Schor’s well-established position on that front, one appreciates that Schor is taking on the entrenched terms of signification head-on.

For example, in the case of Schor’s three paintings entitled Trace, the single word “trace” is written/painted differently across the center of each canvas. We look to assess what “trace” may mean both literally (via the mark made on the canvas) and metaphorically (with respect to recording a past event, invoking the relationship of signification to memory). Is it, in Lacanian terms, the residue of a traumatic episode? If so, whose trauma? Schor’s? Mine? Yours? All of the above? Or, is she invoking “trace” as a type of repetition? In these works, Schor presents the creation of meaning as a type of accumulation that defies stability or convention.

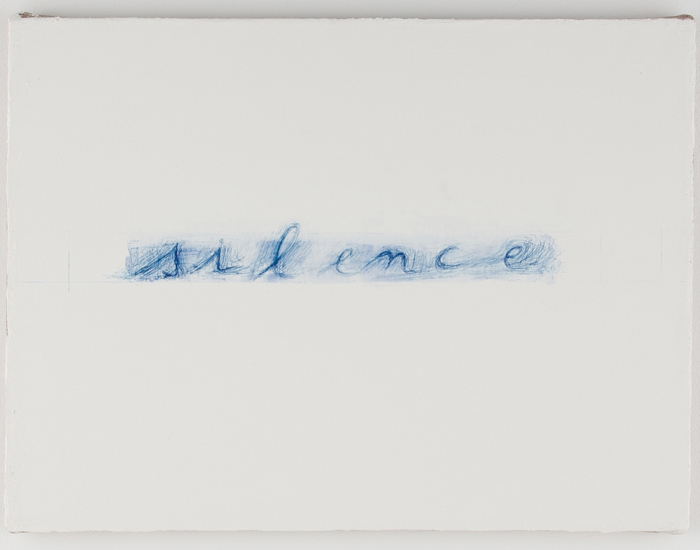

Mira Schor, Silence, 2006. Ballpoint pen and oil on linen, 12 x 16 in. Courtesy of the artist and CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles.

I am referring to these early paintings as the “word and punctuation series” because that’s pretty much what’s represented on the canvas…and then some. In addition to the usage of the word, it is important to note the part that punctuation also plays within Schor’s oeuvre. Assuming an assertive, and at times even aggressive, role in the show’s early works, punctuation echoes the body as an orifice, a clitoris, or a cut. In Semi-Colon in Flesh Comma or Mirror in the Flesh (1994), commas and semi-colons are surrounded by pubic halos. These works conflate the female body as a unique signifier with punctuation. And in doing so, they suggest that the sorting out of the body is a proposition that is as open to interpretation as it is unstable.

For Schor, the surface of her paintings is a skin. Or to borrow a Lacanian phrase, a “stadium”2 upon which subjectivity comes to be written by an ever-shifting series of conscious and unconscious events. And it is upon this public surface/space/body where pre-linguistic meaning—in other words, affect—meets the signifier head on. In Schor’s iconic painting Flesh (1997), we see the word literally carved into the surface of the paint— representation itself as an act of mutilation. Like instinctual hairs that stand on end when one feels either threatened or seduced, the body has its own language. The material qualities of Schor’s paintings both reflect and provoke such a response. As if the paint were icing applied with a spatula, Schor’s surfaces are one part marzipan and one part wound; a membrane that provokes the mouth as well as the eye. Flesh in particular marks this link between the oral and the visual. And since language is spoken as well as seen, these works can’t help but inhabit the mouth. It is in the mouth where the idea straps on the chute and takes one last look back before leaping forth as expression, identification, or subjectivity. However when words fail, the idea—as desire—sits heavily in the front of the mouth, stopping-up the hole. Lacan used both language and its limitations to try and give voice to that stopping-up. Likewise, Schor punctuates her body of word works by placing a modest white painting at the end of the gallery wall. Etched in ballpoint pen across the painting’s creamy white surface is the word “silence.”

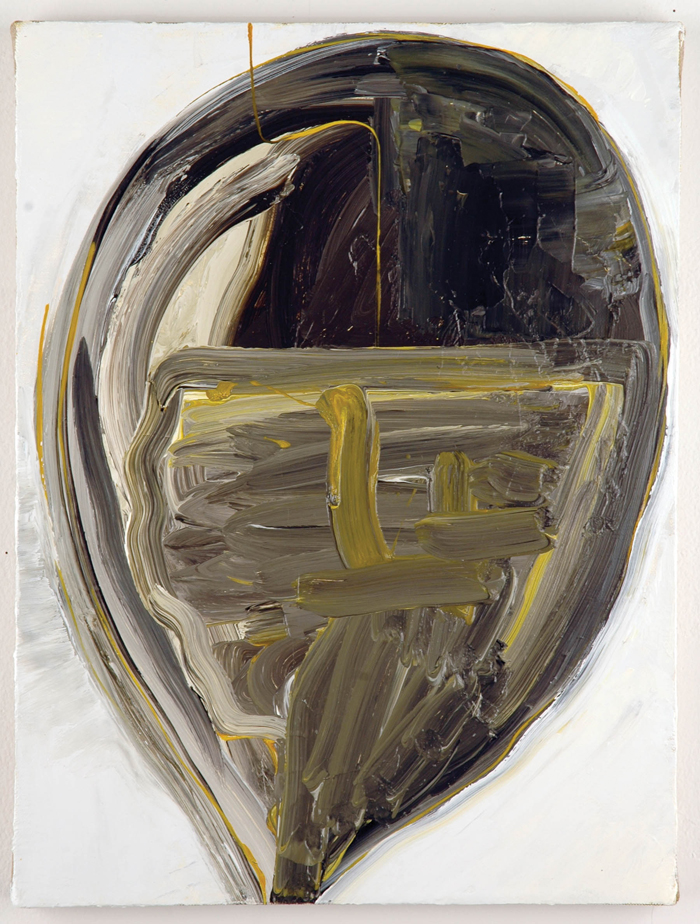

Mira Schor, I’m Fine, 2008. Oil on linen, 16 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist and CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles.

Silence (2006) is a pivotal work in that it foreshadows the following three paintings: Blank Slate (2007), Portrait of My Brain (2007), and I’m Fine (2008). These works offer a provocative transition between Schor’s word paintings and the exhibition’s final figurative works. Where the word paintings tackled Lacanian terms of subjectivity, now the words are gone. In their place are empty thought bubbles soiled with gunked-on paint. The bubble becomes a head or lumpy balloon whose tail runs off the canvas, suggesting a permeability between that “empty” space within the bubble and that which exists beyond the picture plane (real or imagined); in effect representing thinking (or not)…outside the box. What Schor is painting within that space is not empty. What the viewer is facing are marks on the canvas (traces?) as some form of communication before or beyond speech. And when one considers Schor’s dedication to art as a social practice, the seepage between real and imagined, between pre- and para- linguistic (and representation’s contribution to that negotiation) looms large. Be it Shock & Awe, Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, the collapse of the world’s financial markets, or a more intimate, personal trauma, I’m Fine reads as a portrait of denial born of desperation.

In these three works, the textual gives way fully to affect. Not only has “what one says” or “what one thinks” left the scene, but so has “how one says it.” In place of the assertive criticality seen in Schor’s earlier word paintings, one now reads vulnerability and the creep of abstraction. What are words for? What are pictures for? What is paint for? How does one paint their failure?

Two friends are stranded on a deserted island. Starving, each stares longingly at the other. A thought bubble pops-up over each friend’s head showing the other dressed like a Thanksgiving turkey.

In cartoons, desire rises up like a bubble, floating just above a character’s head, creating a place to speak. Though separate, the bubble always maintains a connection to the body it speaks for. Within Blank Slate, Portrait of My Brain, and I’m Fine, the act of painting asserts its necessity most emphatically. No longer feeling served by the word or its critical implications, Schor looks solely to the medium that is painting and courts abstraction. Yet abstraction traffics in a wholly subjective realm of signification. And given Schor’s awareness of the narcissistic bent that such a realm poses to her historically critical project, such a move is telling. No longer knowing what to say, but having the confidence in the tools with which to say something, Schor now stands with one foot in the muck of abstraction and moves cautiously towards figuration.

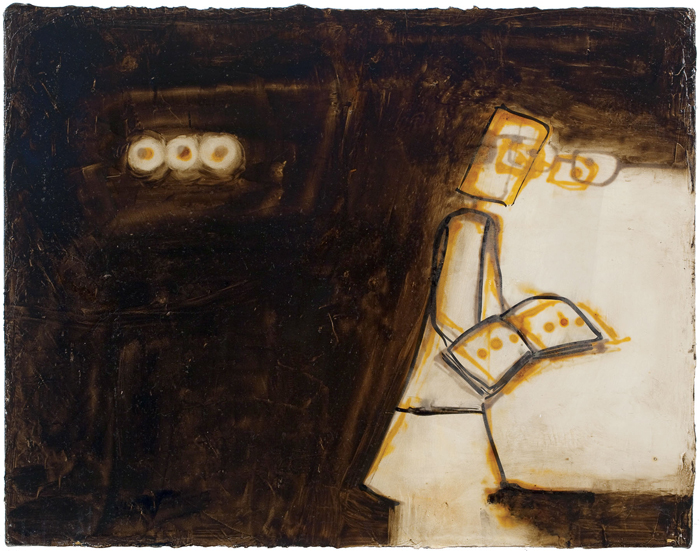

The exhibition’s final series of paintings can best be described as self-portraits. As comic as they are tragic (and thus, revelatory), Schor now paints herself as a stick figure. In these works, the figure (Schor in a dress wearing her trademark glasses) is seen sitting, reading, writing, thinking, and walking. At first glance, the paintings come across as a type of storyboard or hieroglyphic; presenting the self as a diagram: “This is me sitting”; “This is me reading.” However, when seen within the context of the full exhibition, what is actually happening is much more complex. Somewhere between a comic strip and cave painting, Schor is representing the self as a schematic. In effect, by rendering a sketch of what one does, one sees one’s self…as in a mirror. It is through this act of recognition that the self is then spoken. No longer stopped up, now the idea is free to leave the mouth: “This is what I do”; “This is me.”

Mira Schor, Three Periods, 2010. Oil and ink on gesso on canvas, 14 x 18 in. Courtesy of the artist and CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles.

It is important to note that in these recent figurative works, punctuation reappears as an ellipsis or, as stated in the painting entitled Three Periods (2010), a series of three consecutive periods. How does punctuation figure into figuration? How can we read this almost twenty-year transition from Semi-Colon in a Flesh Comma to Three Periods? Is it an arc that leads from a signifier of inclusion, addendum, or coda to a point of closure? Or can we interpret three periods as an affirmation of a future, an unknown, a vulnerability? As “to be continued…”? Or do we see them as repetition, an echo of a single period, as in “end of story. Period.”?

Again, Schor presents meaning as a collision of possible readings and moves forward. Three Periods may well be a metaphor for closure or repetition, but it is also one that offers up three distinct points of departure. Where the word may have failed Schor in I’m Fine, these later works reveal a coming to terms with those limitations in favor of the pictorial. It is this truce (however provisional) that makes Schor’s hybrid practice, as both a painter and a writer, seem all the more fitting.

Mira Schor, A Life in the Mirror, 2008. Oil on linen, 18 x 25 in. Courtesy of the artist and CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles.

Hanging behind the front desk in the gallery is a single, pale, grey-white painting titled A Life in the Mirror (2008). It depicts a balloon hovering in front of a mirror. A thin string of paint tethers the balloon to its reflection. On the balloon’s face are the words “a life” written in cursive; its verso reflection, “efil a,” stares back from the mirror. As if all the paintings in “From the Nineties To Now” have found their way into this one piece, the work offers a sober portrait of the self existing both within and outside of language.3 In A Life in the Mirror, the balloon is a figure is a bubble is a floating word that gains or loses presence by collecting and losing air (as in breath). Again, Schor’s painting asserts the body (specifically the mouth) as both beginning and end point. Written on the balloon—”a life”— recalls balloon-a-grams (“Happy Birthday!”) but its dignity (sans exclamation point) resonates with Schor’s earlier explorations of the pre-linguistic and affect. The painting echoes Schor’s appreciation for the critical terms and conditions that inform the discourse surrounding the body and its interiority. It speaks eloquently to her awareness that “a life”—as a painter, a writer, a witness— is an elusive confection of affirmation and approximation.

Michael Minelli is an artist and educator living in Los Angeles. He is currently a member of the artists collective WPA and teaches both critical studies and studio methods in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts.