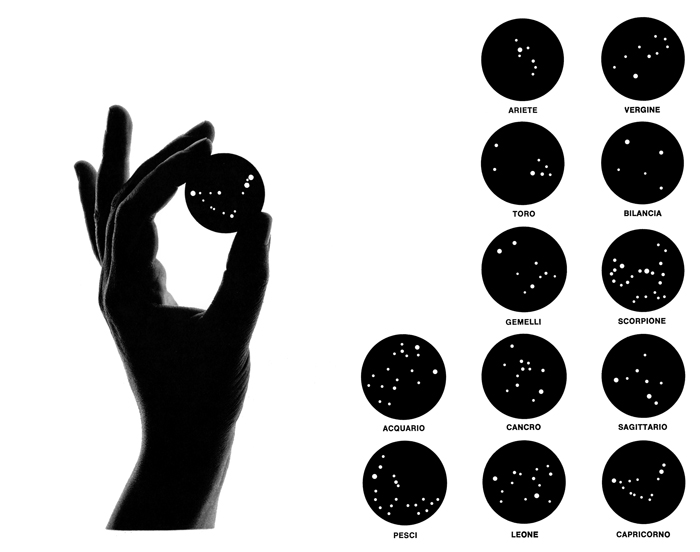

Bruno Munari, Constellations of The Zodiac, 1975. Pierced silver discs. © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

The egg has a perfect form even though it comes out of a butt.

-Bruno Munari1

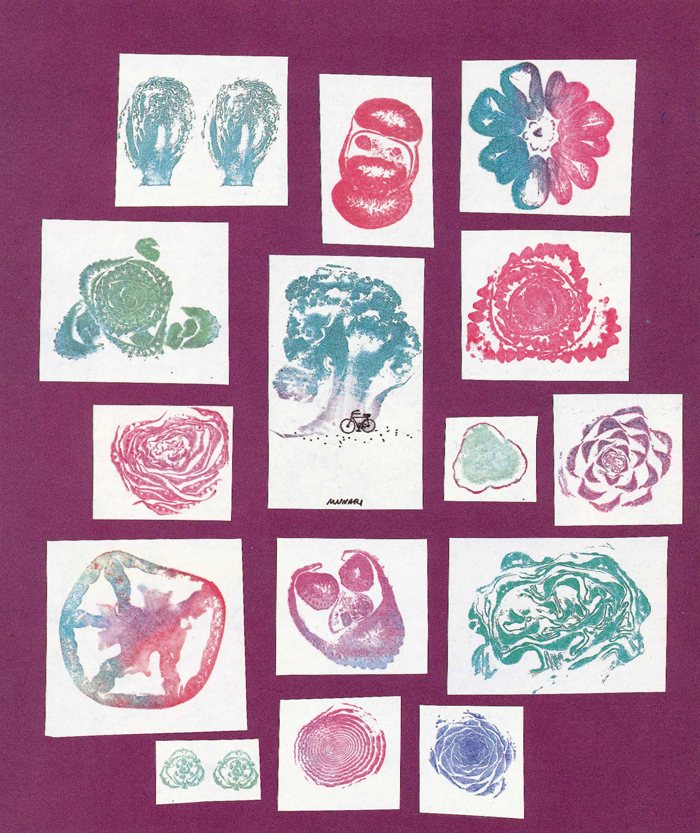

I never thought looking at a Xerox copy made in the 1970s of some string swirled around on a copier’s glass would lead to months of research, slide lectures, and inspiration for several projects, plus a class syllabus. At the public library, I stumbled across Bruno Munari’s Roses in the Salad (1973), which opens with the invitation: “Let’s go to the greengrocer and get: three Treviso radicchio plants, a cabbage lettuce, a Romaine lettuce and some chicory.” Out of the book, into the produce aisle–I like that. In Roses, Munari’s dissected vegetable matter turns into a visual record of rainbowinked vegetable stamp prints: child’s play is transformed into hybrid design-craft and free-spirited studies of color and shape.

Bruno Munari, Roses In The Salad, 1983. Stamps issued from salad. © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

You might wonder why a trip from the library to the grocery store ends up in art, not in salads. If so, you haven’t yet met Bruno Munari, or you don’t know you have. You might have been brought up on some of his children’s books or seen his Calder-like mobiles called Useless Machines. These hanging sculptures illustrate his artistic beginnings as a Futurist in the 1920s and ’30s with a deep interest in the malleability of time and form. His Futurist beginnings also informed his ongoing rejection of avant-garde elitism, which informed his long career as one of the most influential designers of the 20th century. Born outside Milan in 1907, Munari developed a lifelong interest in the connections between product and process, between the maker and the user. According to Timo de Rijk in the design catalog, Bright Minds, Beautiful Ideas, Munari “loathed the pseudo artistic attitude of artist-designers…and designers who accepted the commercial fashionability of products.”2 His products, graphics, and artists’ books served as sly commentary for his support of “consciously unconscious design.”3Munari was a fan of simplicity, which he believed was found in both nature and children. He eventually renounced his design career to lead international children’s workshops he called Laboratorios, beginning in 1977.

Munari also published articles and books of essays about the overlap of art and design and the changing roles of art in contemporary society, perhaps the most famous being Design As Art. His creative life was guided by a Zen principle that “change is the only constant in the universe.”4 While I don’t know what Munari’s religious beliefs were, there is evidence that he admired Japanese culture’s rejection of modern consumer society, and that he had many fans in Japan as a result of his travels there.5 I see the critically astute philosophy of Zen Buddhism, which could be misconstrued as carelessness, as a self-aware, easygoing bravery that comes with relinquishing control. This courage seems to infuse Munari’s art, design, and writing processes. He is and should be a continuing inspiration for contemporary artists interested in books and zines and collages.

Bruno Munari, The First Children’s Workshop In Brera, Milan, 1977. © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

I started making zines as a teenager, not as diaries but as practice journalism, as a way to fix my stance on fantasy topics. I made newspapers that gave equal, front-page space to politics and poetry. I made a Haiku chapbook collecting works penned beside a local stream, and, like zillions of other teen girls, I made fanzine dream journals about rock stars. Later, I mocked my girlie style by overemphasizing it, curating other artists’ works into photocopied magazines about unicorns, werewolves, and women mirror-gazing in horror films. Until recently, I was embarrassed by my shoddy design style and wannabe editorial goals.

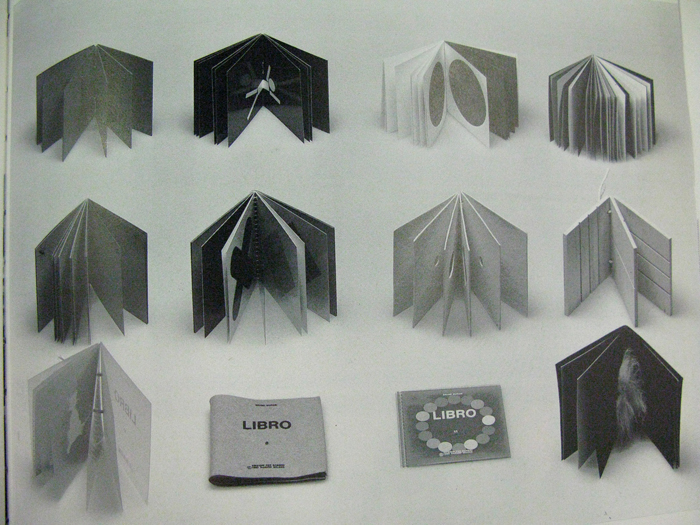

But as I become more entrenched in my text-based writing career, my zine-making has become an escape from verbal thinking. I now think of my handmade books as play projects crucial to my overall creative practice. Munari’s Pre-Books (Prelibri), first published in 1980, encompass this sensibility much more capably than my zines by creating spaces for tactile play to encourage musing and contemplation. The twelve small Pre-Books are made of “materials like transparent plastic, cloth, paper, and wood. They are meant to tell stories through the visual, tactile, sonorous, thermal, and physical.”6Munari’s Pre-Books offer sensory exercise in such a way that I think of them as zines. While the Pre-Books were intended for pre-verbal play, zines are, obviously, intended in general for older audiences. Yet many hand-built zines, mine included, can arguably be considered small acts of tactile rebellion against text-based books, relishing in the idea that one can do much more with books than read them.

Bruno Munari, Prelibri (Prebooks), originally published In 1980. Currently published by Corraini Edizioni. © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

Munari prepared the world for the idea of taking craft-based experiment seriously. For him craft meant using meager materials, like paper, to build artworks by hand. In the 1977 essay Fantasia, Munari states what can be thought of as his design philosophy: “To discover means to find something that one didn’t know about before, but which already existed.” Munari was a fan of “destroying all that he had said and done in the past, [to] rouse the creative spirit to action again.”7 In the two decades prior to publishing his 1971 treatise, Design As Art, Munari had influenced a move towards the eradication of prejudice against humble material, which led eventually to the work by a group of artists christened Arte Povera. In the mid 1950s-’60s, for example, Munari was concurrently in Milan with Arte Povera artists such as Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni. He was certainly part of the times in offering art with an ” optimistic, technological, progressive approach, with a smattering of irony and lightness.”8 Munari and many other Italian artists began to publish their ideas in journals, some which are still published, and to make art renegotiating the definition of the true artist as separate from an outmoded, elitist avant-gardism. In his 1966 essay, “Programmed Art,” Munari wrote:

Artists who care about the uniqueness of the work of art and its corresponding value, about personal style as a commercial investment, about gestures, chance discoveries and artistic scandals… All this is on the way out; it belongs to a vanished world and no longer has any prospect of establishing genuine communication with the public. In my view, we now need to conduct researches with a view to re-founding a true, objective visual language that can naturally and intuitively communicate the dynamic factors determining our new knowledge of the world. A true visual language, that is, comparable with that which characterized old-fashioned static art in the days when it was thought of as a craft.9

By the time he published Design As Art in 1971, Munari had already lived this practice and had faced its repercussions. In Design As Art’s preface, he recalls:

All my friends rocked with laughter, even those I most admired for the energy they put into their own work. Nearly all of them had one of my useless machines at home, but they kept them in the children’s rooms because they were absurd and practically worthless, while their sitting rooms were adorned with the sculpture of Marino Marini and paintings by Carra and Sironi. Certainly, in comparison with a painting by Sironi, scored deeply by the lion’s claw of feeling, I with my thread and cardboard could hardly expect to be taken seriously.10

While this apparently self-deprecating (or subtly sarcastic) quotation refers directly to Munari’s hanging sculptures (which he first experimented with in the 1930s), we can apply it to his sculptural book-making practice. Both are both counter-creations, provocatively titled Macchine Inutili and Libri Illeggibili, respectively. His Illegible Books, known also as Unreadable Books, were books made as visual treatments and experiments in form. They seek the same “harmonic relationship between all the parts” that his kinetics did. The same could be said about his children’s books.

Bruno Munari, Libro Illeggibile (Unreadable Book), 1966. Proof and actual edition for The Museum Of Modern Art. © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

Roses in the Salad is one of a series of books referred to as The Workshop Series. This series, recently back in print, also includes Drawing a Tree, about plant symmetry, and Drawing the Sun, a meditation on shadow, color, and ways to portray the sun. The first four books in the Workshop Series were drawn from Munari’s educational workshops offered for children. In these workshops, Munari focused on the positive creative imagination of kids “who come out of school happy and laughing,” rather than dwelling on institutionalized Modern Art. In his essay “Mystery Art,” he asks of Modern Art:

Is this not perhaps the mirror of our society, where the incompetent landlubbers are at the helm, where deceit is the rule, where hypocrisy is mistaken for respecting the opinions of others, where human relationships are falsified, where corruption is the norm, where scandals are hushed up, where a thousand laws are made and none obeyed?11

With this set of books in hand, I was hooked.

Another book in The Workshop Series, Original Xerographies (1977), which Munari described as “methodical studies performed on an electrostatic copier,” was comprised of what he called original copies.12 To generate these copies, he moved paper around on the platen glass and turned the photocopied errors into discreet works of art. Munari’s simple but brilliant concept was rooted in his love of play and movement.13 During the golden age of the photocopy art movement (from the 1970s to the 1990s), artists such as Joan Lyons, Penny Slinger, and Johanna Vanderbeek widely regarded Munari as the founding member of what is referred to in a 1979 photocopy art catalogue Electroworks as Generation One: the first artists to experiment with this new medium. The curators of Electroworks used Munari’s Xerox tests as a springboard to organize a print exhibition of artists who used copier techniques. In Marilyn McCray’s introductory essay, Munari is hailed as the one who “discovered he could use a machine like a pencil for a new type of drawing.”14

Bruno Munari, Original Xerographies, 1977. © Bruno Munari. Courtesy Corraini Edizioni.

We can regard Munari as another overlooked forerunner to several generations of contemporary artists whose primary tactics in regards to collage and printed matter are decentralization and decontextualization. Consider how the success of collage or appropriation in contemporary art is often based upon how well the reconfigured imagery subverts its intended symbolism in its new context. Take, for example, works from the late ’70s by artists like Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, who are often associated with the Pictures Generation. Their radical and sometimes politically driven appropriations and interventions are often associated with the rupture of post-modernity, but many of their strategies can be traced to the Berlin Dadaists, in particular, Hannah Hoch, Raoul Haussman, and John Heartfield. Is Munari missed as a precedent because of a Modernist firewall between fine art and design? I hope we have come farther than that.

I am aware of the influence in my zines of 1980s street graphics and DIY fanzine aesthetics, but Munari’s interest in the ever-changing, and his love of yielding unintended or unknown results through common means, makes me wonder if Munari has influenced me subliminally. Munari expressed a DIY attitude precisely:

Great art (bourgeois in conception, handmade by the genius only for the wealthiest) no longer makes any sense. Art for everyone is still this kind of art, at a lower price, still has the whiff of genius about it, leaving everyone else with an inferiority complex. The technological possibilities of our era allow anyone to produce something with aesthetic value. They allow anyone to destroy his inferiority complex in the face of “art,” to put into action his creativity, so long humbled. One of the duties of the visual producer will be that of an experimenter, of trying the tools and passing them onto the next, along with all the “trade secrets,” that assist the process of making.15

Giving away one’s technique is generous, but it also presents a challenge: Can you make something awesome? His instruction manual is a production call.

In Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism, author Alison Piepmeier claims that zines are more than a hobby-craft, and that they are, in fact, a burgeoning political strategy of third wave feminists. I found Piepmeier’s history of feminism’s “tradition of informal publishing” fascinating and informative. She traces the tradition from 1850 to the present, starting with women who worked as scrap-bookers, health pamphleteers, and mimeographers, in short, back to feminism’s first wave.16 During feminism’s second wave–the 1960s and 1970s Women’s Movement–mimeographs and pamphlets distributed by health collectives revolutionized information about female sexuality, giving rise to such classic manuals as Our Bodies, Ourselves. Piepmeier notes repeatedly that the love of the physicality of zines binds historical female self-publishers to a future, fourth wave of zine-makers who are “comfortable with art and media culture.”17

Trinie Dalton, from left to right: Touch of Class, 2004; Werewolf Express, 2005; Mirror Horror, 2008. All images courtesy of the artist.

Piepmeier’s text, in conjunction with my studies of Munari’s work, has encouraged me to consider zines as substantial critical contributions. I find it exciting to think of flimsy, photocopied pamphlets as works of art and feminism. Some artists, like the musician-collective Chicks On Speed, mock the notion of taking zines seriously with a consciousness and aesthetic I admire. Their It’s A Project (2003) is a Fluxkit of sorts that melds fashion with fanzine into a package that contains clothing patterns, posters and a catalog documenting their career. It’s designed under that DIY, cut-and-paste rubric attributed to punk and to feminist art aesthetics. While they are dedicated to their practice and career, the band does not take this zine-style overly seriously: their motto is “Fuck Art Let’s Craft.” This reminds me of Munari’s decision to renounce avant-garde art in favor of working with children, not because he favored naivete, but because he appreciated understandable, accessible art and design.

Munari’s ultimate call to production, Original Xerographies, along with the rest of his books, raise the bar for measuring book-art quality, especially in regards to those photocopied works we call zines. I’m glad Piepmeier elevated the conversation about zines, but some of the works she discusses in her book are not what I find aesthetically appealing. If zine-makers, especially females, don’t want to be “laughed at,” as Munari puts it, they must do more than scribble their political opinions onto 8 1/2 x 11 sheets of paper and run them through copiers. If anything, I hope my essay can serve as a new call to production. If Munari is great because he discovered a means to channel fun, lighthearted art practice into skilled engineering feats, it is up to contemporary artists, including myself, to marry rebellious concept and craft together into something as yet unfathomable. In Munari’s terms, that would be a work of art that offers a new take on what’s in front of us.

Trinie Dalton has authored and edited five books. She teaches bookbinding and artists’ book courses at Pratt and NYU, and teaches fiction writing in Vermont College’s MFA Writing Program. Her work can be viewed and read on www.sweettomb.com.