In what are called the new schools…all individuals have an opportunity to contribute and to which all feel a responsibility.

—John Dewey

We do not always create “works of art,” but rather experiments; it is not our ambition to fill museums: we are gathering experience.

—Josef Albers

It is nearly impossible not to feel great affection for Leap Before You Look. It is a flush curatorial offering of art and artifacts, timelines and supergraphics, props and performances that celebrates the influential arts curriculum of Black Mountain College, an independent liberal arts institution that emerged in the United States in the 1930s, when progressive educational philosophy was at its peak. Re-introducing an alternative history of creative learning today, when all ranks of public education in the United States are under a full-on assault from both state and federal governments, curator Helen Molesworth presents a timely exhibition that is perfectly engineered to trigger a sentimental affect in its viewers. In the new vertical shadow of accountability mandates, such as the No Child Left Behind Federal Act and the Common Core State Initiative in primary and secondary education, which has trickled up to art schools and art departments across the country, the power of experimental education as practiced by Black Mountain College is dead-in-the-water, a progressive relic of the twentieth century. “What was encouraged, what was engaged in at Black Mountain College—both by student and by artist/teacher—was experimentation.” 1 Experimental learning, the touchstone of Modern progressive education, has pronounced Enlightenment roots that emerged out of the stultifying conventions of pedagogical rigidity, rote memorization, and punitive discipline. Jacques Rousseau’s Émile (1762) radically destabilized the foundation of traditional French education, and his belief in the philosophy of natural goodness altered social conceptions of childhood and childhood development.

His treatise summoned educational reforms that spared children from lecturing teachers so that the lessons of nature could be absorbed. Rousseau wrote, “Our first teachers of philosophy are our feet, our hands and our eyes.”2 In continental Europe, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Friedrich Froebel, and Maria Montessori advanced the doctrines of natural education by evolving classroom practices, inventing teaching tools, and shaping curriculum. In the English-speaking world, William James and John Dewey were influential proponents of the belief “that knowledge arises from reflection upon our actions and that the worth of a putative item of knowledge is directly correlated with the problem-solving success of the actions performed under its guidance.”3

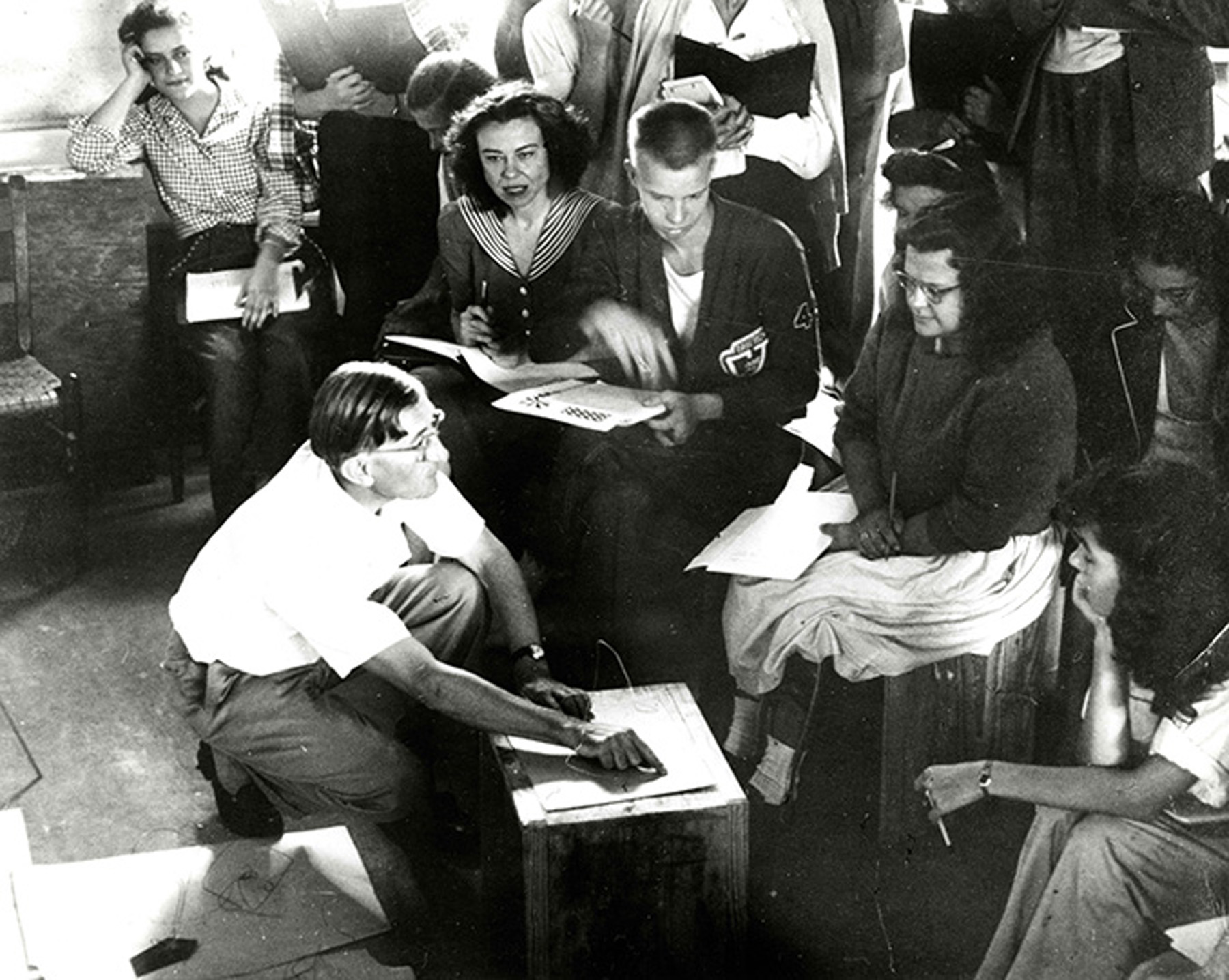

Josef Albers’s color-theory class with Nancy Newhall, Ray Johnson, and Hazel Larsen Archer, n.d. Courtesy Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina, Ashville, NC.

Dewey’s Experience and Education was published five years after the 1933 inception of Black Mountain College. His seminal Art and Experience was published in 1934, nearly contemporaneous to the college’s beginnings. The college’s founder and first rector, John Andrew Reed, was a colleague of Dewey and an educational theorist and scholar in his own right. Through Reed’s invitation, Dewey sojourned at the college in southwestern North Carolina multiple times, joining its advisory council and personally supplementing the school’s library. Reed affirmed and implemented Rousseau’s once radical principle that “each student is an individual who blazes his or her unique trail of growth; the teacher has the task of guiding and facilitating this growth, without imposing a fixed end upon the process.”4 Moreover, the belief that knowledge is built through play, direct experience, and social interaction involved a political dimension that was “essential for nurturing an individual’s capacity to participate in a democracy.”5 Black Mountain’s founders championed the doctrine of “education for democracy” and the moral aspects of firsthand engagement in creative work by engaging the professional and the amateur participants with utopian principles.

Barbara Morgan, Photography Class in Cabbage Patch, n.d. Courtesy Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina, Asheville, NC.

Of course, the twentieth century’s most notable design school—the Bauhaus—threaded its influence through Black Mountain College’s structural bones as consciously as the underpinnings of education’s progressive movement. But the Bauhaus’s vigorous professionalizing métier differed greatly from the philosophical ethos taken up in the American school. Black Mountain was the new institutional home for exiled Bauhäuslers Anni Albers, Josef Albers, Xanti Schawinsky, Lyonel Feininger, Stefan Wolpe, and Walter Gropius. And works by Paul Klee, Herbert Bayer, and Wassily Kandinsky were frequently on view at the college. Despite its shared human resources, Black Mountain College celebrated the creative, nonprofessional artist with individuated ambitions while Bauhaus training developed specialists dedicated to the production of art and design. If the Bauhaus “is the servant to the workshop and will one day be absorbed by it,” Black Mountain was its antipode where classes quickly gave way to independent creativity and unguided work.6 This difference was demonstrated both in classroom curricula and in pedagogy. Josef Albers’s teaching at the Bauhaus was dedicated to technical mastery; he shifted to perceptual exercises imbued with the ethical underpinning of personal achievement in the American school. And, as I will later address, it was also an ideological shift that Albers adapted for his own studio practice at the college.

Leap Before You Look, and the brawny exhibition catalog that accompanies this traveling show, highlights the college’s educational successes and its utopic clichés in equal parts. It does this in a non-hierarchical patchwork of objects, artifacts, and numerous terse scholarly contributions. A compelling and wistful feature in the exhibition and the catalog is that both are generously punctuated with black-and-white images from a cache of historical photographs documenting the school’s everyday moments. At times these pictures reinforce Molesworth’s loose historical sketch, but they also operate independently of it, eliciting their own narratives and storylines. This is especially the case with a few iconic photos, which depict the school’s creative exercises and social interaction and make repeat appearances as exhibition didactics and catalog illustrations. These are not important photographic artifacts, but they conjure the Black Mountain College ethos more effectively than most of the artwork on display. Two examples of this sort of storytelling include the charming picture of students with cameras exploring a cabbage patch and a selection of Kodachrome slides depicting portraits of students and faculty creatively adorned on the occasion of a Valentine’s Day Ball. One of these ochre-tinged images discloses a formally posed Josef Albers wearing a sea-sponge beard and mirrored eyeglasses.

Buckminster Fuller arrived in 1948 as a first-time teacher, and students’ active engagement with his geodesic architecture is well documented. Popular with colleagues and the student body for his grand mystical vision, Fuller employed his aluminum sphere models as specimens of a totalizing geodesic future. “The models were visual metonyms for the quantum or atom-age thinking that Fuller promoted from the postwar period until his death in 1983.7 Two of these spherical models are included in the exhibition, along with a pen-and-graphite drawing by Fuller that features a loose, freehand delineation of his systemized geometry. The drawing also includes a definition of the word “synergy” (“behavior of whole systems…”) written out in red alongside the irregular symmetry. The many photographic images that record the students’ playful interaction with his large-scale exterior models, which appear to double as the college’s jungle gyms, convey Fuller’s impact as a spellbinding metaphysician as well as a teacher of architecture.

Geodesic dome held aloft by students, summer 1949. Photo by Masato Nakagawa. Courtesy Black Mountain College Project Papers, Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina, Asheville, NC.

The inclusion of a shuttle loom retrieved from Black Mountain’s weaving workshop, an example of the wooden desk used by the college’s students, and a dance floor, complete with a companion piano used for live performances, stretch the already heavily didactic exhibition into a faux campus atmosphere. This illusion is reinforced by the deployment of five monumental vinyl backdrops picturing the college’s working milieu and marking the exhibition’s thematic transitions in the galleries. Also culled from the school’s photo archives are super-sized documents of classroom instruction, group work, leisure, and the college’s rural environment. Graphically seductive, these monumental images bolster the utopian ideals of the college’s progressive philosophy toward education and, to a great degree, demonstrate the schism between the experience of the school and its artistic output.

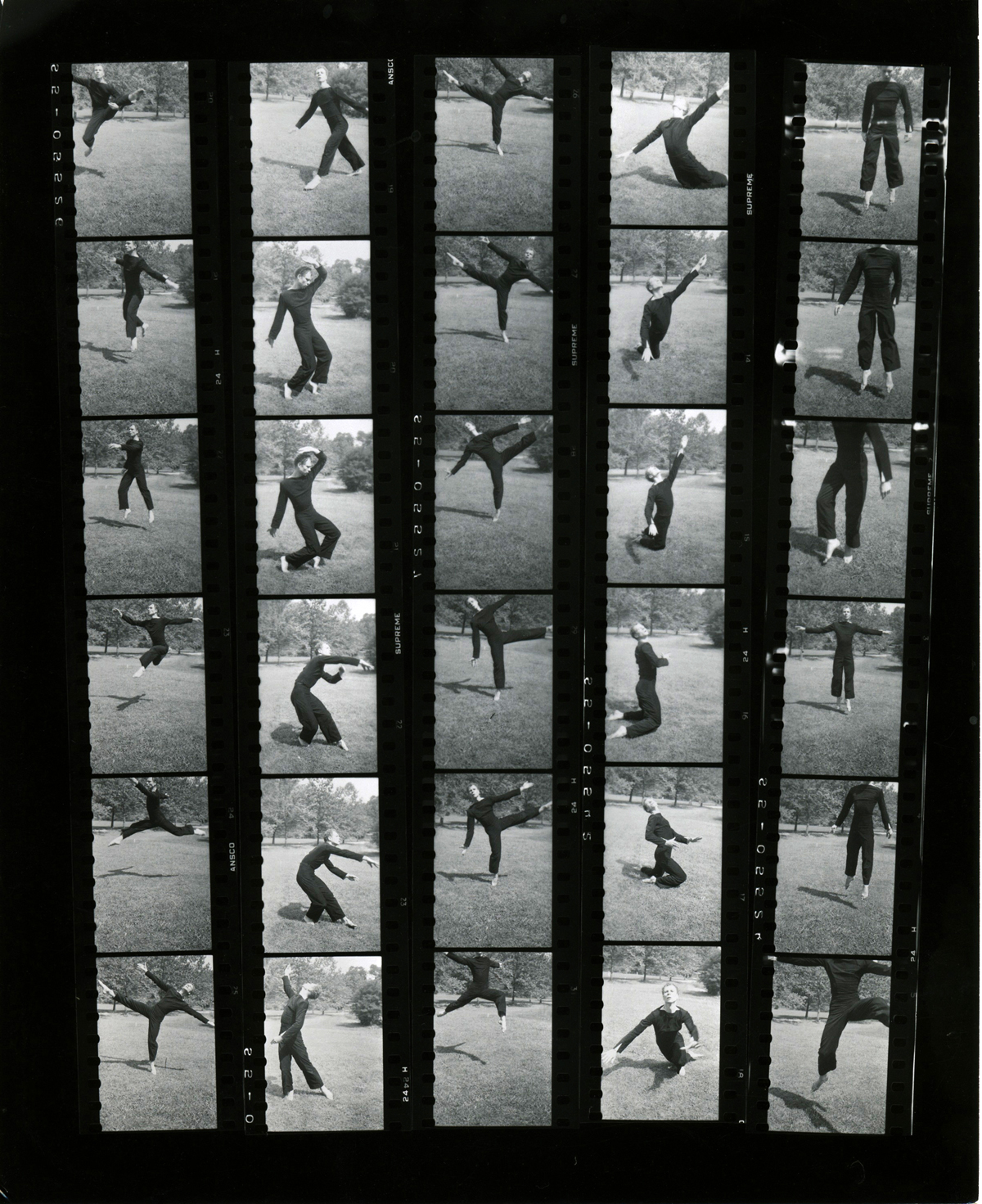

Photographic documentation is an important part of the Black Mountain story, but photography was also a component of the school’s curriculum. Leap Before You Look includes 13 photographs by a less famed participant—Hazel Larsen Archer. Archer arrived in 1944 and maintained a continuous relationship with the college until 1953. She learned from Fuller to understand and value the structural principles inherent in nature and to see the “essence of invisible relationships.”8 Several of her small silver prints depict patterns of shadow and light falling over the surfaces of campus architecture. These intimate photographs evoke an elegant interrelationship between timeless geometries and the continuous flux of nature. Together with her iconic images of Merce Cunningham’s singular dance movements and the soft-focus, low-contrast portrait of colleague Ray Johnson, these photographs demonstrate her belief that art and experience are built on “continuous moments of touching the unknown.”9 And for Archer, fine printing and compositional clarity were as essential as capturing those continuous moments of process and experimentation in a photographic language. Despite publishing her photographs widely and achieving “national recognition through a solo exhibition at the Photo League,” Archer abandoned photography a few years after leaving Black Mountain College and “turned her full attention to education.”10

Hazel Larsen Archer, Katherine Litz in Dining Hall, ca. 1952–53. Gelatin silver print, 7 × 6 inches. Image courtesy of estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.

Varied and numerous, the examples of Anni and Josef Albers’s work in the exhibition offer a satisfying understanding of the experimentation that was foundational to Black Mountain College. The breadth of their works represented develops a rich trajectory of influence and imagination that was both inspired by and led to new strains of American modernism. Anni Albers’s woven room dividers, the neck pieces made in collaboration with Alexander Reed—symmetrical jewelry built with commonplace sundries such as paperclips and corks—and her humorous and illusionary knot drawings extend an imaginative scope to her no-nonsense approach to textile construction and her dedication to and mastery of loom craft.

Anni Albers and Alexander Reed, Neck Piece, 1940. Aluminum strainer, paper clips, and chain. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society New York. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art.

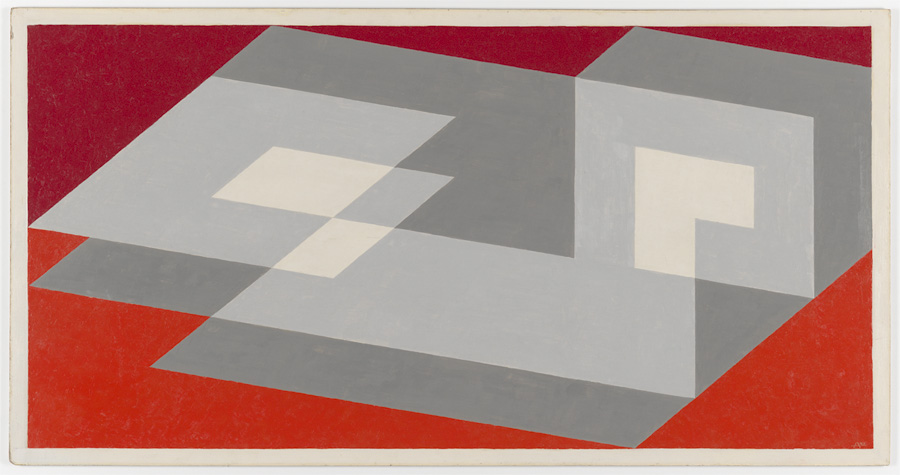

Josef Albers has been described as a dedicated pedagogue who believed art education should aim at “being something” instead of “getting something.”11 At Black Mountain College, his own technique and imagery opened up. It was a tremendously productive period for him, and he exhibited widely in the United States during his 16 years as resident faculty.12 There he “showed interest in a multiplicity of approaches, for example, demonstrating the geometric could be as free as freehand, and freehand as abstract as the geometric.”13 In color-motivated compositions executed in oil on Masonite and linear geometries cut from woodblocks and printed with black ink, Albers protracted the formal and material language of abstraction. Albers’s travels to Mexico and pre-Columbian architectural sites in 1942 inspired a series of optical prints titled Graphic Tectonic. Variant/Adobe (1947), painted toward the end of his tenure at Black Mountain College, reveals the seeds for his eminent series Homage to the Square. Vibrating orange and gray rectangles arranged in a slightly irregular horizontal symmetry indicate his growing preference for compositional simplicity and an emphasis on active color.

Josef Albers, Tenayuca, 1943. Oil on Masonite, 22½ × 43½ inches. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Purchase with the aid of funds from Mr. and Mrs. Richard N. Holdman and Madeleine Haas Russel. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Ben Blackwell.

Regrettably, much of the work by the college’s other widely celebrated faculty and alumni, including Kenneth Noland, Elaine de Kooning, John Chamberlain, Franz Kline, Ruth Asawa, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Jacob Lawrence, and Cy Twombly, occupied the exhibition in a scant and compulsory fashion. The works representing many of these artists are neither sufficiently experimental nor exemplary demonstrations of their practices. But some other individual works in Leap Before You Look stand out, including Carnivorous Plant #22 (1952), an amber-colored translucent polyester resin and wire sculpture by the Japanese émigré Leo Amino. This abstract three-legged figure posed on a two-tiered wooden base offered a clear contrast in material experimentation to Mary Callery’s bronze figurative sculpture Study for Pyramid (1949). Peter Voulkos’s Rocking Pot (1956), with its unsteady rocker base and its pierced and inverted hand-thrown volume, is a nod to rock and roll as well as to the avant-garde choreography of Merce Cunningham. The ceramic sculpture’s celebration of movement challenges the traditionally static nature of the craft. Rauschenberg’s Minutiae (1954/76), a sewn, painted, and collaged freestanding assemblage, which functioned as sculpture and screen for performances, is another exceptional inclusion. Of Minutiae, Molesworth writes, “It is simultaneously a summation of all that Rauschenberg learned at Black Mountain and a launching pad for the postmodern era.”14 It is also a teaser for a much more extensive look at Rauschenberg’s Black Mountain College experiments and collaborations with fellow artists Cage, Cunningham, and Jasper Johns in Rauschenberg’s forthcoming retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

The college also incubated new forms of music, dance, and poetry, under the tutelage of many avant-garde talents including Cage, Cunningham, David Tudor, M. C. Richards, Charles Olson and Robert Creeley. Occupying the final gallery of the exhibition, a grand piano and an elegant copper and iron wire sculpture by Asawa populate the periphery of a large in-gallery dance floor where performers from L.A. Dance Project executed early chance-based choreography by Cunningham to music composed by Christian Wolff and Cage. This live programing was rounded out with Cunningham dancer Silas Riener performing a reassembled composition of Cunningham’s 1958 Changeling. When performers were not activating the gallery, a black-and-white video of an original performance of Changeling was projected onto the wall behind the empty dance mat as both an archival gesture and a live-performance simulacrum. Music in the form of a “Soundscape” was also available for the exhibition audience, including a range of pieces from Ludwig van Beethoven and Arnold Schoenberg to John Cage and Stefan Wolpe. After a quiet start, music at the College became pioneering. In 1939, only nine students enrolled in the college’s music program, yet five years later it hosted the consequential Schoenberg festival on the occasion of the composer’s 70th birthday.15 In 1948, Cage was in residence and deployed the ironic work of Erik Satie, redirecting the College’s Schoenberg cult and its infatuation with emotional tonality toward the impersonal and the inchoate.

Hazel Larsen Archer, contact sheet of Merce Cunningham dancing, n.d. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.

In the 1950s, poet Charles Olson took over as rector. His aim was to find a stratagem to keep the college vital and cohesive after the departure of the Albers’ in 1949. Olson hired Robert Creeley to teach and to edit the college’s literary magazine, The Black Mountain Review. Facing a dire need to increase enrollment and bring in badly needed tuition dollars to keep the institution operational, the magazine was designed to function as both a promotion piece for the college and a site for Olson and Creeley to self-publish. All seven issues comprising the publication’s history were on display in the exhibition. The fall 1954 issue was open to a short arousing poem written in the same year by Creeley, titled “The Whip.” It opens with “I spent the night turning in bed.” In opposition to New Criticism, the dominant poetic theory of the time, the radical Black Mountain Review was “intensive, reductive and sharp.”16 “Creeley’s editing and design turns it into an effective vehicle for his and Olson’s post-modern agenda.”17Yet despite The Black Mountain Review’s crucial contribution to the American midcentury literary scene, the school was forced to shutter its doors in 1957. By then, most of the college’s faculty and students had departed North Carolina, and many had become immersed in New York and San Francisco’s experimental post-war cultural waves.

As a school built on progressive pedagogy and animated by an experimental curriculum in rural American, the success of Black Mountain College was necessarily conditional. The numerous authoritative histories and dissertations that have aggregated over a half century crystallize the avant-garde institution into the exemplar of experimental arts education. Alternatively, this exhibition sought to restore what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari call the “nonsequential energy of lived historical memory and subjectivity” into the official chronicle.18Molesworth asserts, “I felt certain that there could be no definitive text that could tell the story of the years between 1933 and 1957 in the environs of Black Mountain.”19 In her catalog essay, she writes that her research yielded both facts and gossip. In addition to marshaling “the facts into a narrative,” she also embraced the fictional potential of gossip as a means to challenge the official truths of the college’s history.20 “Ultimately the logic of gossip spurred me to avoid the romance of a story with a beginning, middle and end, in favor of a tale structured by polyphony, fragments and a narrative strategy of alloverness.”21

Rather than perpetuating the existing narrative of the college, Molesworth pieced together a polyvalent project that undoubtedly enlivened the familiar history. But her rhizomatic treatment of the college’s history missed an opportunity to address the current crisis in education, especially the state of curricula in arts education. For those of us invested in arts education, debating assessments and outcomes in the studio classroom has become an all too frequent exercise, as we labor under the increasingly powerful institutional mandates to professionalize art degrees. Despite the organizers’ bricolage desires, Leap Before You Look left no room to question the educational and artistic value systems that shape the present. Instead, through archives and artifacts, it found a new way to further underscore Black Mountain College’s historically unique ethos by successfully fracturing a twentieth-century American success story into a multitude of stories, each of which originated from the Black Mountains of North Carolina.

Michelle Grabner is the Crown Family Professor of Painting and Drawing at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She lives in Milwaukee, WI.