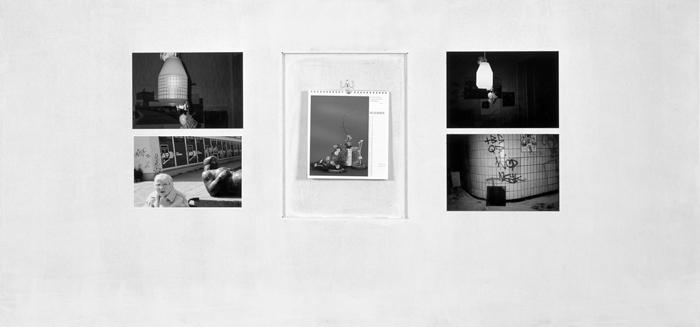

Manfred Pernice, exscape, installation view, 2006. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White.

Manfred Pernice’s (German, b. 1963) new multi-part installation at Regen Projects requires of the inquisitive viewer—or more saliently in this case, the conscientious reviewer—significantly more reflection, research, and wrestling than do most exhibitions. To say that the conceptual aims and aesthetic commitments of this installation are obtuse and elliptical is to understate the case. Were one to take a casual five-minute stroll through the gallery, one might quite easily leave feeling bemused, unmoved, even resentful, such is the opacity of the work. This is not to suggest that Pernice’s aesthetic strategies are without merit and reward. It is, however, to suggest that those rewards arise from a type of deep, laborious, at times even unpleasant engagement atypical in an art market that once again places a high premium on craft, careful finish, and beauty. None of these descriptors applies to exscape, an exhibition title which riffs on the little-known Chilean Surrealist artist Roberto Matta’s (1912-2002) pictorial exploration of the “inscape,” a three-dimensional space emblematic of the human psyche. The objects Pernice has gathered, fabricated, and arranged at Regen Projects do not dazzle, bewilder, or provoke wonder in any conventional sense; at first glance, in fact, their appeal is not at all optical. Rather, they seem to resist, even repel, close aesthetic scrutiny. The primary imperatives of the show, then, are to look searchingly, to think hard, to persevere despite initial discouragement, and to hope that a reward of some sort eventually materializes.

On one’s immediate right upon entering the gallery is a hastily painted white wooden board that leans informally against a wall. Of the nine images displayed on the board, four are photocopies in both color and grainy black and white of paintings by the self-taught French Surrealist painter Yves Tanguy (1900-1955), whose practice might understandably be confused with his eminently more famous Spanish counterpart, Salvador DalÌ (1904-1989). But while DalÌ’s forms are more often than not mimetic and recognizable, if distorted, Tanguy’s uncanny forms—which are frequently strewn throughout somber, indeterminate landscapes—have only the faintest connection with recognizable objects in the world. Pernice includes one such image, the aptly titled Metaphysical Landscape (1935) on his whitewash reference board of imagery. The fanciful idea evoked in this work-that a pictorial landscape might simultaneously make visible the profoundly invisible human psyche, while also representing (to some extent) the observable world—provides a key to Pernice’s project. While there is no doubt that such a key is required for an installation as conceptually elusive as exscape, the crude story-board aesthetic Pernice has elected to use here is so devoid of charm, craft and visual interest that its deliberately provisional character reads less as an aesthetic device than as a floating afterthought. It becomes clear as the rest of the installation unfolds that Pernice takes as one of his ostensible subjects the beautiful decay of European urban spaces. However, while Pernice’s decision to mimic this timeworn character in his installation allows his work to operate in aesthetic consonance with his subject, this tactic does very little to generate visual or intellectual interest.

The artist’s attempt to evoke this beautiful decay aesthetic is far more successful elsewhere. Adjacent to the whitewash board is a steel sculpture entitled ikebana 1 (2006) centered on a white pedestal affixed to a large, slightly raised, black platform. The presumably found elements of elegantly quirky contorted steel that compose this sculpture are rusty and blotted with patches of white paint that enliven the slowly decaying steel to create an unlikely—and unintentionally—arresting abstract surface. Ikebana, the Japanese art of floral arrangement, has been traditionally committed to attenuated, linear compositions radically different from the bursting, volumetric arrangements most common in the Western tradition, and this interest is echoed quite obviously in Pernice’s sculpture. More subtle and provocative, however, is the simple fact that over time flowers inevitably degrade much like the industrial materials in various states of collapse that evidently interest Pernice. The implication that there is beauty in the ephemeral lends a melancholy aspect to this work, especially when one considers that this sculpture may represent the ultimate fate of the metropolises in which we live.

Manfred Pernice, ikebana 2 (detail), 2006. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Joshua White.

Another whitewashed bulletin board, ikebana 2 (2006)—this one affixed to the wall to the rear of the black platform—provides a segue of sorts between the steel sculpture and the remainder of the exhibition. The central image is a garish calendar page that shows a synthetic, Ikebana-like arrangement of materials in a configuration that clearly informed the composition of the adjacent sculpture. Though manifestly different and not as seductive as Pernice’s sculpture, the formal relationship between the two is apparent. This image is flanked by two luminous photographs of bamboo and paper lamps, and additionally by two unrelated images that describe in an uncompromising documentary manner two variously decaying urban landscapes. One of these photographs shows an old woman, her mouth open animatedly, sitting next to a figural bronze in the manner of Henry Moore, with a wall of modular red squares in the background that has been over-written with graffiti. The other photograph captures a wall of light yellow tiles covered with graffiti in what looks like a subway station, the frequent use of the space palpable in the littered floor and stained wall. Because the content and presentation of this information is so insistently prosaic, and because the internal logic that links the imagery is so personal and thus inaccessible, ikebana 2 does not settle into an argument or thought, but rather appears arbitrary and ultimately stultifying.

The remainder of the show is dominated by oversized, architectural maquette-like objects, distributed with an eye for subtle spatial awkwardness (evocative of Tanguy’s paintings) across two distinct planes. One is slightly elevated and covered with rough carpeting, and the other a matte, gray linoleum triangle almost flush with the gallery floor. These quirky polyhedrons incorporating altered tetrahedrons, off-set rectangles and flattop pyramids, all of a roughly human scale, are washed with a layer of thin white paint, and overlaid with roughly taped passages of yellow, red, blue, green and black that pick up knowingly on the clean modernist lines and tired urban colors seen in the aforementioned photographs. The correspondence is far from exact, but that is not the objective. In exscape 5 (2006), for example, a broad conical form layered with interlocking strips of light blue, green, yellow and black sits atop a dirty white polyhedron inscribed with passages of like colors. The strategy here seems quite similar to that employed by Tanguy in his metaphysical landscapes. However, while Tanguy invented nebulous, organic forms and distributed them at will throughout his desolate, arid landscapes, Pernice presents unidentified fragments of nonspecific architectural shapes, which—though unmoored and functionless—nonetheless manage to evoke through color, shape and feel the rich, used texture of an urban environment.

Manfred Pernice, ikebana 1 (detail), installation view, 2006. Photo: Joshua White, Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

With exscape Pernice suggests that the abundantly decorated modern urban landscape, in all it’s discordant, hodge-podge glory, records in its surfaces our history, and as such may also provide a basic visual vocabulary to describe the existential experiences and concerns of those who have lived and will live there. While Roberto Matta and Yves Tanguy sought to describe the interior space of the human mind using a pictorial language of their own invention, Pernice, by contrast, draws on the incidental, quotidian details of the manmade world to achieve a similar effect, and in doing so suggests, perhaps, that we are as much a product of it as it of us. That said, Pernice’s self-consciously abstruse visual strategies do very little to make some of his more interesting ideas accessible or compelling. His consistent use of quotation, for example, becomes a sort of shorthand for conceptual ideas that are not adequately parsed out in the objects that comprise the exhibition. Ultimately, the complexity of this installation arises less from the concepts that drive Pernice’s project and more from the elliptical, obtuse language he has chosen to represent them.

In the work of many contemporary artists, a premium is placed on developing a formal language consonant with—or honest to—one’s subject and/or conceptual motives. Though heavily criticized, Matthew Barney’s megalomaniac CREMASTER series is a signal example of this strategy. Barney’s conceptual premise—to describe the social and biological development of a (presumably) American male—is rendered in highly personal, metaphoric terms that harmonize with the myriad complexities of his chosen subject matter. Whether his epic series is ultimately convincing or not, Barney has conjured an inordinately complex visual language, which, when used to describe his narrative, appears not as arbitrary pastiche of elements, but rather as a persuasive system of thought with sound internal logic, despite—not due to—its complexity. Barney understands that visual art allows for certain frivolous leaps in logic and faith, which in turn allow artists to suggest arguments and establish connections far too laborious, tedious, or patently absurd to propose in, for example, academic writing. Pernice uses a similar strategy in this installation, but the opacity of the presentation obscures rather than emphasizes his ultimate argument—whatever that might be—and the unfortunate result is that one wants to be anywhere but inside the exscape.

Christopher Bedford is a PhD student at the University of Southern California and a Curatorial Assistant in the Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the J. Paul Getty Museum.