Multiple visual perspectives span the drawings, animations, and gaming PC that are distributed across Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s solo exhibition, Second Sex War, at Gasworks, London.1 The works combine the point-of-view of the 3D avatar EVA v3.0 with pose sets (predesigned 3D animation poses based on human actors) in what the artist describes as “post-human porn production.”2 Second Sex War explores the politics of female and non-binary sexuality and pleasure through Hansen’s newly commissioned works and collaborations with animator James B Stringer, designer Nikola Dechev, artist and producer Kepla, and Nkisi (Melika Ngombe Kolongo), a female artist, DJ, and producer. The exhibition’s title refers to Simone de Beauvoir’s pivotal feminist text of 1949, The Second Sex, which argues that women have historically been treated as secondary to men. Hansen extends this line of inquiry into the continuing objectification and commodification of embodied experience that finds new forms through digital technologies.

In DICKGIRL 3D(X) (2016), EVA v3.0 brandishes a phallic sex toy, which she uses to penetrate a large clay-like form; the act is seen in different positions from different viewpoints. The 3D model protagonist cuts the abstract form with a scalpel, seeming to sculpt and mold it to reflect and fulfill her desires. This animation plays on a hanging monitor that is suspended by a structure that evokes a hybrid of exhibition display and BDSM hoist. On the soundtrack “Exotica,” by Nkisi, samples of breathing suggest EVA v3.0’s pleasure as it breaks into high-powered beats that insistently underline the forceful acts portrayed on screen.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, DICKGIRL 3D(X), 2016. Virtual reality production and CGI animation. Courtesy of the artist. Credit: Werkflow Ltd, London. Commissioned by Gasworks in partnership with Trondheim kunstmuseum.

Nearby hangs Methylene Blue Diluted by Female Ejaculation (2015), which combines body fluids with a loose drawing style to offer a non-binary form of genitalia. The resulting drawing represents a body that exists outside of normative medical classifications of sex by anatomy, which is also reductively used to assign gender. The artist describes a related series of laser-cut drawings on plywood as “low-tech manual craft.”3 These works share the freehand expression of bodily experience, as compared to the outsourced skilled digital labor of Hansen’s other works, although they are mediated through laser-cut technology. The loosely drawn outlines of non-binary bodies contrast with the slickness of her CGI works, but in all of these projects, her characters float in a decontextualized void. The drawing iSlave (non-dualistic) (2016) asserts non-binary gender identity and submissive and slave positions in BDSM. Its title also alludes to the individualist consumer ethos of products with the “i” prefix and suggests how contemporary expressions of non-binary and BDSM sexuality are mediated or enabled by digital technologies; this includes online forums and apps such as KNKI and Whiplr used to communicate, share fantasies, and organize IRL meet-ups. In combination with the 3D avatar and virtual reality gaming set of DICKGIRL 3D(X) and SECOND SEX WAR ZONE (2016), the artist also alludes to avatar identities and the simulation of more extreme BDSM activities in the virtual realm, such as within Sims and Second Life.4 In another drawing, a figure penetrates a car petrol tank in an expression of commodity desire and fetishism, or mechanophilia. In No Baby (2015), we see a sleeping female-bodied figure. Above her head floats a dream bubble in which a fetus has been circled and crossed out, as if the protagonist dreams of sexual pleasure liberated from functionality and the consequences of procreation.

The Gasworks press release calls No Right Way 2 Cum (2015), a CGI animation that Hansen made with James B Stringer, a “feminist ‘cum shot’ video.” Kepla’s grinding and pulsing soundtrack—“Selfplex”—suggests the body and its industrial complex and the ideology of individualism at the core of neoliberalism. Like the other digital works in the exhibition, this animation features Hansen’s 3D model protagonist EVA v3.0, which was created by designer Nikola Dechev as a stock avatar for the adult entertainment company TurboSquid. In No Right Way 2 Cum, EVA v3.0 appears at first to conform to the straight male gaze; her blank face allows for projections of stereotyped gender roles, such as the “passive” female. But Hansen empowers her protagonist with female-bodied actions that undermine this perception. She is depicted masturbating and experiencing female ejaculation as a proclamation of self-pleasure. Hansen’s representation of the act of female ejaculation should be viewed in the context of the recent attempts in the United Kingdom to censor and regulate representations of “non-normative” female-bodied climax in pornography, as well the use of “slut shaming” in wider media as a form of regulating female desire.5

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, No right way 2 cum, 2015. Virtual reality production and CGI video. Courtesy of the artist. Credit: Werkflow Ltd.

According to the artist, No Right Way 2 Cum was inspired by a series of female ejaculation workshops that pro-sex feminist Deborah Sundahl has been running for over 30 years.6 In 1984, Sundahl and Susie Bright founded what they described as the “first lesbian erotica magazine,” On Our Backs, and a poster for the publication can be seen in the background of No Right Way 2 Cum’s CGI room. On Our Backs was founded amidst the collective feminist debates and “sex wars” of the 1980s, which questioned, among other things, whether representations of porn and BDSM in popular culture constituted forms of empowerment or subjugation for women. The magazine’s title was chosen in response to another journal, Off Our Backs, which included a number of articles by anti-pornography feminists who argued that pornography was violently exploitative of women who were already systematically oppressed.7 In contrast, On Our Backs forcefully debated sex-positive interpretations of porn, arguing that it was—or could be reclaimed as—a medium for feminist sexual expression.8 In her use of porn industry images and methods to create her own iconography, Hansen manifests the latter position.

Toward the end of No Right Way 2 Cum, the CGI footage of EVA v3.0’s body begins to break up. Shots of the interior and exterior of her body merge, invert, and take on the appearance of stretched skin. As the camera breaches the surface of her skin, it suggests that she is merely a vessel. But her subjectivity and desire are forcefully re-asserted when spurts of her CGI cum hit and trickle down the screen, forming the letters that comprise the title of the work.

In SECOND SEX WAR ZONE, which Hansen made with the digital arts studio Werkflow Ltd., gallery visitors engage with EVA v3.0 by wearing an Oculus Rift Virtual Reality headset while reclined on a cushion on the floor. Through tilting the headset at different angles and in different directions, we explore the terrain of EVA v3.0’s body in close-up, viewing her from above and below. We can see EVA v3.0’s face, but her eyes are obscured by or replaced with reflective discs. When we try to engage with her in virtual reality, “we” are not visible in the mirror reflection; instead we see only the same empty CGI studio as in No Right Way 2 Cum. The figure of EVA v3.0 suddenly backflips and stands upright at a further distance, evading our gaze and escaping the proximity that VR promises. At other times, the avatar’s cis-female body possesses a prosthetic phallus lit up by a swirling blue pattern; we are positioned as her submissive counterpart in an act of role-reversal. The “war zone” of the title suggests the ongoing renegotiation of the power dynamics of dominance and submission, with EVA v3.0 moving between being the subject and object of the work. The viewer’s full-body engagement in the VR animation of SECOND SEX WAR ZONE heightens the impact of its sudden switch of perspectives. The artist uses the sensory, immersive dimension of the work to create tension between the viewer’s potential sexual arousal, in response to its hypersexualised imagery, and the stymying effects of experiencing the works in a public exhibition space.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, SECOND SEX WAR, 2016. Installation view, SECOND SEX WAR ZONE, Gasworks, London. Gaming PC, Oculus Rift headset, beanbag, vegan leather beanbag. Credit: Werkflow Ltd. Commissioned by Gasworks. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

In DICKGIRL 3D(X) (also made with Werkflow Ltd. in 2016), EVA v3.0 molds and remolds a brown clay form; she penetrates it and aggressively cuts it until it appears to seep blood. Her actions present the female-appearing body not only as the site of violence and control but also of retaliation and resistance. This violence between EVA v3.0 and the clay object also relates to a broader structural violence. In both No Right Way 2 Cum and DICKGIRL 3D(X), the artist explores the processes of 3D modeling as a parallel to how human bodies are socially constructed and altered to conform. EVA v3.0 is created by scanning actual body parts separately, fragmenting and isolating them, and recombining them through software to reconstitute a “whole” and idealized form. Scans of “flesh tones” (as they are referred to in the cosmetics and prosthetics industries, and now also in CGI) are mixed together to generate a new skin, which is then mapped onto the outline of the template body. The skin has elements of photorealistic textures and color variations, and it appears glossy and reflective, perhaps with sweat. But it also bears traces of reconstruction that have not been completely smoothed out, appearing in parts like skin grafts.

In SECOND SEX WAR ZONE, the camera zooms in close on EVA v3.0’s skin. It’s amalgamated appearance and mottled pink-brown color leads one to question not only the obvious idealization of the female body but also the inherent racial bias in 3D models, which are frequently designed to be “white” by default. Across the gallery, Cite Werkflow Ltd. (2015), a clay relief sculpture with a flattened impression of a face, has similarly blotchy skin tones; its physical, handmade imprints echo the digital scans required for EVA v3.0’s fabrication. In the animation, the grid-based design of the body seen under the avatar’s “skin” recalls the obsession with measuring and comparing inherent to the disciplines of anatomy and medicine. In Hansen’s 3D animations, EVA v3.0’s new skin appears to be continuing to grow in excess of the underlying structure, suggesting that it won’t be constrained, as well as suggesting artificial skins produced or grown in laboratories for grafting. The avatar’s skin then assumes the earthy tones of the clay form that she was manipulating, suggesting that both skin and clay are mutable.9

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Cite Werkflow Ltd., 2015. Face imprint in clay, terra sigillata, and wax. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

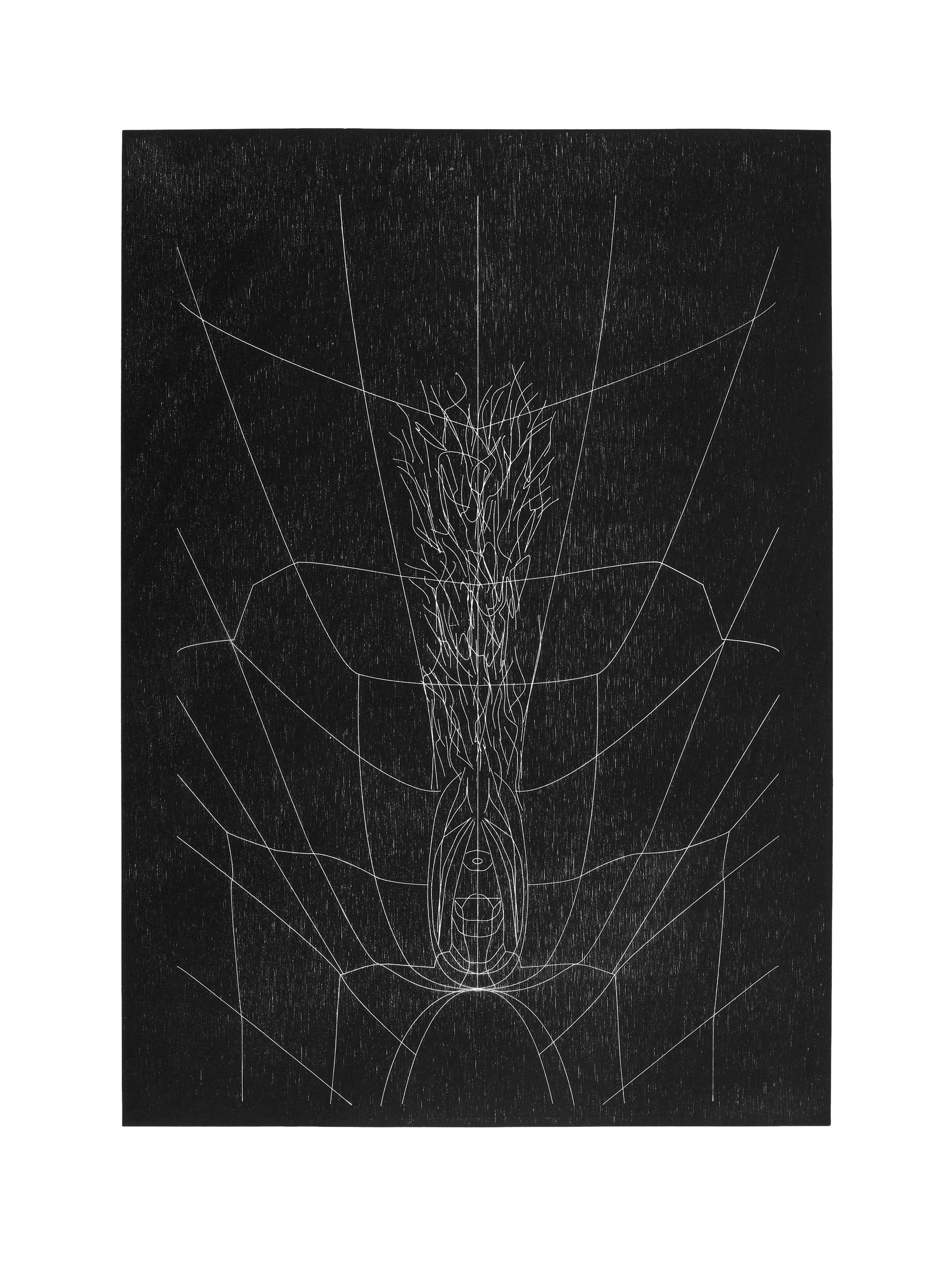

Hansen’s woodcut print series HIS CORPORATE CUNT ART, credit Nikola Dechev (2016) is based on an image from the user manual for the “morph control” function of EVA v3.0’s vagina. These tools allow the user to choose not only which 3D model to use but also the internal workings of her body for his or her own simulated sexual pleasure. Consumer demand for anatomical accuracy in the creation of sex dolls and avatars has been increasing, including detailed mimesis of the physical affects of sexual activity. Hansen’s print series brings to mind the manipulation of non-virtual female-bodied sexual organs (including increasingly popular cosmetic procedures, from waxing and piercing to surgical labia removal and vaginal “tightening”) and questions who is the audience for the production and ownership of representations of female genitalia.

HIS CORPORATE CUNT ART, credit Nikola Dechev takes an image of Dechev’s EVA v3.0 out of the commercial context of 3D model design and translates it back into a physical form, then re-positions it as a commodity for sale through the gallery. Hansen appropriates from the socially and financially more accessible gaming sector to produce an art object that is rarified yet at the same critically evaluates the mode of its production.10 The title also acknowledges the wider infrastructures of contemporary art in which commercial and nonprofit art institutions are complicit with the corporations that fund their activities that support artists. This resonates specifically in relation to the funding of Gasworks’ recent £2.1 million redevelopment, which made possible the gallery’s commission (in partnership with Trondheim Kunstmuseum) of the newer work in Second Sex War.11 Hansen’s work brings to mind the male-dominated technology sector, in which the 3D model was made, and its often slick, corporate aesthetics, and it implies that the likely buyer of the prints will be male and work in the corporate sphere. In a talk called “Possible Objects of a New Feminist Art Practice,” which accompanied Hansen’s exhibition, Josephine Wikstrom claimed that, in questioning the notion of formal labor relations and inequalities between different sectors of art, technology and corporations, and given its sex-positive feminist content, Second Sex War also points to the “hidden labor” in women’s roles in biological and social reproduction.12 This includes affective and emotional labor in interpersonal relationships and unwaged domestic work and childrearing, which still are undertaken predominantly by women.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, HIS CORPORATE CUNT ART, credit Nikola Dechev, 2016. Woodcut on paper, 25¾ x 8¾ inches. Courtesy the artist.

Hansen produced the ceramic sculpture CULTURAL CAPITAL COOPERATIVE OBJECT #1 (2016) in collaboration with artists Manuela Gernedel, Alan Michael, Georgie Nettell, Oliver Rees, Matthew Richardson, Gili Tal, and Lena Tutunjian; the artists collectively own the finished work. The surface of the large, rectangular, black-and-white wall-mounted relief is scored into imprecise grids that skew the tightness of those used in CGI animation.13 The work’s scraped clay surface mimics the processes of cutting the clay object in DICKGIRL 3D(X), and impressions left by shoes evoke the bodily imprints in Cite Werkflow Ltd. By including a collectively produced work in the context of a solo show, Hansen and her collaborators lead viewers to question the status of artists as “brands” in the contemporary art market. The project is representative of Hansen’s ongoing interest in exploring alternative strategies for artists to work in or around arts institutions. For example, she participated in a conversation with Nils Norman on the subject of the artist-led collaborative project Parasite (1997–98).14 Parasite, which was initiated by Norman and Andrea Fraser, used the infrastructures and facilities of the New York arts institutions PS1 Clock Tower and The Drawing Center’s Project Room in exchange for “cultural capital.” The project represented an attempt to reclaim autonomy over the distribution and value of artists’ work independently from commercial galleries. The inclusion of this collective work in Second Sex War also suggests parallels between the embodied pleasures of art making and sexual activity, and the vulnerability of these shared experiences to being co-opted and commodified by market structures.

Manuela Gernedel, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Alan Michael, Georgie Nettell, Oliver Rees, Matthew Richardson, Gili Tal and Lena Tutunjian, CULTURAL CAPITAL COOPERATIVE OBJECT #1, 2016. Ceramic relief, mixed clay. Commissioned by Gasworks in partnership with Trondheim kunstmuseum. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

SECOND SEX WAR ZONE’s floor cushion in the center of the gallery and the wire-suspended monitor and speakers of DICKGIRL 3D(X) explicitly reference the collaborative and sadomasochistic practice of artists Sheree Rose and Bob Flanagan. Rose and Flanagan’s works questioned the “non-normative” sexual desires of and toward the less able-bodied Flanagan, who had the condition cystic fibrosis, within the power dynamics of BDSM. DICKGIRL 3D(X) mimics the wooden structure of Rose and Flanagan’s 1991 installation Bob Flanagan’s Sick. In 2014 and 2015, Hansen organized a series of interdisciplinary events, This Is Not a Symptom, at South London Gallery. The themes were biopolitics, disability theory, and anti-Psychiatry—the critique of mainstream psychiatric treatment. One of the events included a screening of Sick: The Life and Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist (dir. Kirby Dick, 1997, USA).15 The seminars reflected on the biomedical construction and regulation of the body, including micro-level chemical alterations through hormone therapy and psychiatric medication. Hansen’s related work, Seroquel® (2014) also features the figure of EVA v3.0 and mimics a pharmaceutical infomercial in displaying 3D animations of micro-level biochemical reactions of the medication in the body.16 In a talk called “Always Already Undead: Unbecoming Object,” which accompanied Hansen’s exhibition at Gasworks, Linda Stupart explored alternative strategies of embodied defiance, such as bio-hacking.17 Stupart interlinked different scales of the techno-mediation of the body, from consumer uses of biofeedback technology in fitness and exercise apps to how these were developed by and to serve the military-industrial complex. Stupart also discussed grassroots subcultural subversions, such as DIY Transhumanism, in which people alter and enhance their own bodies without the intervention of healthcare professionals and institutions.

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, DICKGIRL 3D(X), 2016. CGI animation with sound, 3 min loop. 3D design and VR production: Werkflow Ltd. Soundtrack: Exotica by nkisi, 2016. Commissioned by Gasworks in partnership with Trondheim kunstmuseum. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Second Sex War investigates how technologies and the images they produce affect the human body by creating and satisfying sexual arousal. Simultaneously, the artist aims to disrupt those technologies and their modes of representation. Hansen’s works span a range of desires toward and mediated by mechanical and digital technologies, through the machine as fetishized commodity, the architectural structures of BDSM, and the use of interactive Virtual Reality. Hansen explores the co-option of artistic labor and collaborative practice by capital in the art market and culture industry, and possible strategies to evade or critique this from within. She also appropriates 3D model designs to question visual representations made by and for male consumers that reproduce and fulfill conventional aesthetics of the female body, within a wider culture that body-shames those who do not comply. In contrast to the clean lines of the designed body template is the messy discharge of bodily functions, from cum used in the drawing Methylene Blue Diluted by Female Ejaculation to the body fluids on the screen in No Right Way 2 Cum, in which EVA v3.0’s desires are fulfilled rather than the audience’s. We see beyond the superficial veneer of pornographic simulation and fleetingly inhabit the position of EVA v3.0, but our attempts to engage with her directly are refused. The videos featuring EVA v3.0 manifest the tensions between opposing feminist perceptions of pornography as a means of subordination and its potential to embolden female subjects. Hansen’s work engages with and represents the mechanisms of social (re)production and control, as mediated by labor and technology, and the possibility of claiming different perspectives and reformulating power relations.

Sophie Hoyle is a London-based writer and artist whose research explores biotechnology, anxiety as a psychiatric and collective cultural condition, and intersectional analyses of sociopolitical issues.