Zoe Leonard, February 27 2012, frame 30, 2012. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 10 inches. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain and Galleria Raffaella Cortese.

With the Cold War space programs under way, 1960s and 1970s Land art offered a reinvestigation and renewed attention to the territorial human on earth and in space.1 In addition to institutional and post-minimal critique, Land art emerged as a discourse of landscape—associated with nature and dealing with grand scale, remote location, and difficulty of making—to reclaim the earth as material.

In contrast to the panoramic aerial view from above, the work of Zoe Leonard and Katie Paterson reverts the kinesthetic toward an act of looking upward to the starlight and cosmic darkness of the skies. Unlike the land, which is coded heavily with national and territorial impulses, the sun and its cosmic cycle are overlaid with romantic, symbolic, religious, spiritual, humanistic, and scientific values. By attending to the sun as part of the aerial view, as an affective dimension of our lives on earth, and as a singular source for illuminating representational discourse, these artists have shifted Land art’s emphasis from the spatial to the temporal. They show the ways in which we are asking and permitting the sun to do, and the ways in which the sun is always already performing.2 The landscape tradition is one of colonizing distances; Land art’s tradition is one of territorial critique. Leonard and Paterson want to bring down in miniature form more than a token of their findings, but to bring the sun itself to Earth, as a new kind of landscape.3

If imagining the grandeur of earthworks was a response, in the 1960s and 1970s, to the miniaturization of Earth via NASA images, then seeking out the unbridgeable spaces and times of cosmic length is a response to today’s instantaneously networked world. We have come back to Modernism’s utopian universalism and nineteenth-century concerns with romance, poetry, and the picturesque. Indeed, we can go further back and declare that this reversion to gazing upward, seen in Christian paintings well past the Renaissance, may reintroduce through a formal compositional back door, even if inadvertently, the kinesthetic of the sublime and spiritual.

At the Camden Arts Centre, three projects of Zoe Leonard’s from 2009 to 2012 are spaciously installed in three discrete galleries. The works are centered on viewing and how we view what we view, and they reveal a photographer beholding the sun to focus her thinking about the origins of photography and its uses. The first room encountered is an expanse of white, with light from seven skylights flooding the white walls, which in turn are punctuated by ten pale silver gelatin photographs of the sun. These prints, from 2011 and 2012, are from an ongoing series, together called Available Light, and are appropriately presented with no artificial light, unframed and pinned to the walls. Each photograph has its negative’s edge printed black to form a visual boundary, signifying how photography relies on the sun—for subject and process, both the power and significance of the sun—taming its light to the expanse of sky contained within.

The sun pictured materializes as a hazy pale gray blob or a hotspot of near white in an even-toned, vaporous sky. The photograph presents pure light as a subtle sfumato without modulations of shape and shadow. It is commonly held that the first hazy sky in Western Art is none other than Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.4 “For a century before Leonardo, with the exception of a few religious scenes depicting the fires of hell, every Renaissance painting pictured skies with unlimited visibility.”5 Da Vinci incorporated atmospheric obscuration to create compression of the far distance through aerial perspective. However, in Leonard’s photographs, the haze places the sun at a remove—veiled and aloof—and yet corporealizes it; it is both a body that can be veiled and an unattainable sun; it is both indexically present and experientially absent. In fact, these are photos not of the sun but of the “Sun” as sunlight and obfuscation, lens glare and negative grain, and are colorless, like white light and dry heat.

Zoe Leonard, June 3 2011, frame 33, 2011. Gelatin silver print, 13½ × 18¾ inches. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain and Galleria Raffaella Cortese.

Even more interesting is the paradoxical proliferation of a cold, dying sun in the interior of an art viewing space. The portraits and landscapes of the sun are arranged equidistant from each other, punctuating the white walls with hazy gray rectangles, the effect of sameness intensified by the lack of color and the regulated arrangement. What is the meaning of multiple suns, when we live under one sun? Specificity matters since each photograph is titled by date and frame number, and yet, the iterations seem to create an equivalency of time and vision, each day repeated as another, changes in weather or season remarkably going unrecorded.

Indeed, the use of a series emphasizing equivalences also forces the artist’s hand. Compare Leonard’s series of hazy suns to Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents, his photographs of clouds, which were also always shown in groups.6 The Equivalents are commonly recognized as photographs intended by their maker to free the subject matter from literal interpretation, and are historically significant for being among the first abstract photographic works of art.7 In Leonard’s work, it is as if Stieglitz’s clouds are replaced by the sun, or the clouds have thinned into an obscuring veil over the sun. The conceit of abstraction survives the thinning or replacement. Not including a horizon and centering each sun gives a sense of levitating vertigo.8

In photographing clouds, Stieglitz demonstrates how “to hold a moment, how to record something so completely, that all who see [the photograph of] it will relive an equivalent of what has been expressed.”9 Rosalind Krauss has argued that the photographs in Stieglitz’s Equivalents series constitute “masterpieces of Symbolist art,”10 even if Stieglitz’s notion of “equivalents” transformed a Baudelairean and Symbolist concept into an ostensibly personal and “American” one.11 As symbolic works, Leonard’s sun pictures direct our attention to the fountainhead of photographic exposure. What I have elsewhere noted in reference to the work of a fellow artist—who photographed the sun closely cropped and printed c-prints the size of wallet pictures—applies to Leonard’s photographs too. The artist “displaces the ostensible subjects of other photographs and zooms in directly to the very source from which photographs are made, light, and the ultimate source, the sun.… For this photograph cannot be an aid to memory, but an aid to vision.… [T]he photographs achieve a species of divine simulacra, by their failure to reveal an impossible but wonderful origin, the sun.”12

Leonard’s choice of black and white points to their existence as Ur photographs. They index the process of capturing light on paper in slow time, sequentially laid out, unfolding in time for the spectator.13 Viewing black-and-white photography today sets up a situation where a nostalgia for analog infects and occupies the present. Eerily, the photographs feel as if they are long nighttime exposures of the sun, as if the sun could exist in night. The expulsion of color drives the photograph away from light towards nocturnal shades, the pallor of dull grays, as if hinting at the cold alienation and empty subjectivity that faces these blank pictures. These pictures challenge our ability to scrutinize.

The photographs moreover allow us to consider—in our contemporary digital moment—the ontology and genesis of the photographer’s desire to image light. The history of photography is entwined with the sun, conceptually, visually, procedurally, and substantially.14 The sun and its light are ontological subjects for a camera rather than merely figuring the primary source for the work it does. It is not the camera that is heliotropic but Zoe Leonard herself. The sun’s concrete and metaphorical luminescence coalesce in her photographic vision. However, if the camera can render the sun in normal scale within the “landscape” of gray sky, the camera obscura reveals the sun as all-pervasive. At Camden Arts Centre, I was thrust from the bright white room of sun photographs into the dark chamber housing Leonard’s Arkwright Road, 2012, a room-sized camera obscura.15 I was blinded by darkness, before being engulfed in the time of the street. One is reminded that without darkness there is no light.

In her photographs, the sun’s light scatters and fixes; yet it is the sun itself that matters, the shape and look of it. In the camera obscura, it is the light that matters, its arrival on earth refracted and repeated. In Arkwright Road, Leonard extends and reveals the corporeality of replication, giving a new dimension to our reception of time and space through movement and light.16 An unsuspecting spectator might understand the darkened space as a projection room, the lens to the outside as a movie projector, and the real projection as a deferred or delayed recording. Even though Leonard’s camera obscura offers the highest degree of indexicality, with no intervening recording media, paper, or framing device, the wondrous thought is not of objectivity but of the subjectivity of expectation and the affective dimension of real light. It is not a matter of the real and the removed, but of allowing that whatever we do see is indeed part of our reality.

Zoe Leonard, Arkwright Road, 2012. Camera obscura installation: lens, darkened room; dimensions variable. Installation view at Camden Arts Centre, 2012. Photo: Andy Keate. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain and Galleria Raffaella Cortese.

If Arkwright Road in fact participates in the drama of landscape, it does so while turning the scene on its head.17 Without the correctives of putting the image right side up or brightening the dim visual, the work proclaims its identity as a camera obscura piece, no illusions.18 And so it should dawn on the viewer that what is on view is not a projection of a prerecorded landscape concept, but is rather, uncannily, an imperfect view of life and scenography from the ordinary London high street right outside the gallery—with no time delay. What matters here is not the construction of an idealized or instructive landscape, but rather a technological organization of viewing and a specific use of interior walls decorated with archways to interpose the public on the vaguely domestic, to allow us to be both ensconced and alfresco. The work is not a record. It is a dislocated and truncated experience, one whittled down from the all-immersive to a strictly one-way visual. It is an act of viewing without a chance of the gaze being returned, a distillation of Modernist alienation. Insofar as the work is comprised of a disembodied and decontextualized image, one captured within the art gallery if not actually recorded, it is an instance of phantasmagoria not unlike Roland Barthes’s notion of photography as presenting reality in a past state, an ectoplasm, “a reality one can no longer touch.”19 But while Barthes spoke of a past state, that is one with time as the distancing factor, Leonard’s camera obscura renders a current and present street activity as no less a reality one can no longer touch. The gallery is a redoubt from the real world, a dark room in which action is visible but unresponsive to us.20

Unlike the sun photos, where the level of abstraction is so high that there is little to see, Arkwright Road opens up reality for as long as the sun is willing to share. The greatly magnified cars zooming about the ceiling amused me more than seeing the sky at my feet, because it suggested the urban as transported to the heavens—billboards, construction, traffic lights, and all. One acquaintance was amused that that the sign on the cinema across the street read: “IN IMAX 3D EXPERIENCE” in reverse. Although the stereognostic, and thus the proprioceptive, experience of walking down an uninspiring London high street is withdrawn, the gain is cousin to the floating feeling afforded a viewer spending time in Available Light. Arkwright Road burbles and levitates; it is photography in and of the present.

In 1859, Alphonse de Lamartine famously declaimed, “Photography is more than an art. It is a solar phenomenon where the artist collaborates with the sun.”21 If Zoe Leonard’s work relies on the sun’s light, Katie Paterson’s work relies on the possibility of such a light never arriving on earth.

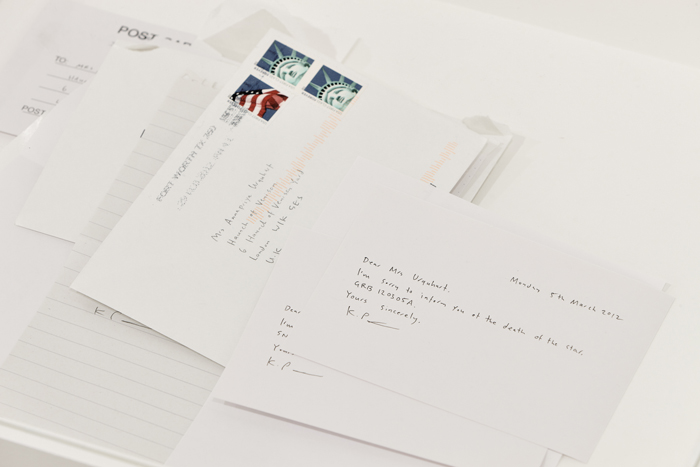

Katie Paterson, The Dying Star Letters, 2011. Ink on paper; dimensions variable. Installation view at Haunch of Venison, London, 2012. Photo © Peter Mallet. Courtesy of Haunch of Venison, London.

The Dying Star Letters, 2011, are a series of letters handwritten by Paterson and addressed to her gallerist at Haunch of Venison, “Mrs. Annapriya Urquhart,” upon learning about the demise of a star from her scientific contacts around the world. The work reflects a very human desire to record and communicate the moment when a scientist notices the transmission of light from a star has stopped arriving on earth, thus intimating its death. The unvarnished truth is announced thus, “I’m sorry to inform you of the death of the star GRB 120305A. Yours sincerely, K.P.” The bland announcement, the serial nature of the communications, the contemporary formality of analog mail—postcards, letters, envelopes laid in a row on a shelf in a gallery—all contribute to a generic matter-of-fact feeling of resignation. Claude Lanzmann’s comment on imaging human death is useful here: “I used to say that if there had been—by sheer obscenity or miracle—a film actually shot in the past of three thousand people dying together in a gas chamber, first of all, I think that no one human being would have been able to look at this. Anyhow, I would have never included this in the film. I would have preferred to destroy it. It is not visible. You cannot look at this.”22 And so we do not look; we write—calmly, mechanically, and acceptingly. And yet, one would hope that one couldn’t help but “look” upon the death of a star without experiencing a twinge of insecurity. Our own star may follow this fate, after all. The Dying Star Letters communicate, from one earthling to another, an awareness of the death of stars beyond our sun, and so by extension, an awareness of the fate of our own solar system. The “unreachably remote” is made even more remote with its passing, but the artist and her human contacts are drawn closer.23

Zoe Leonard’s collection of souvenir postcards of Niagara Falls, in the third gallery at the Camden Arts Centre, addresses and marks the limits of the overwhelming desire to communicate the experience of the ineffable. Unlike Paterson’s single-minded, handwritten address to her art dealer about what cannot be pictured, Leonard has gathered these used postcards because of what they picture. Neatly stacked in piles of varying heights, all facing one way, the 6266 postcards in Survey (2009–12) give nothing away. The title allows one to surmise that the table-top mapping is a survey of the various observation points of the falls, with the stack size graphing the popularity of each view point. It is tempting to turn the postcards over to read them, but one can’t. One has to imagine the variety of responses faced with the same postcard image and the various recipients of these personal notations.24

Zoe Leonard, Survey, 2009–12. 6266 postcards and table; dimensions variable. Installation view at Camden Arts Centre, 2012. Photo: Andy Keate. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain and Galleria Raffaella Cortese.

Paterson, on the other hand, addresses her letters to her art dealer rather than to a lover, say, or her mother, thereby revealing the public nature of her address. The end recipient of the news was always intended to be me, the gallery-goer. The Dying Star Letters intends to bridge several spatial and temporal chasms between the star and my delayed awareness of its death and to create poetry from the urge to communicate the ineffable sublime of a faraway transformative explosion or implosion that is the death of a star.

Is there a genealogy of mourning embedded in here, an “operative memento mori”?25 Paterson’s map work, All the Dead Stars, 2009, available as a limited edition poster, similarly gives vision to a science of unseeable loss. The Dying Star Doorbell (2008) plays a tiny hum close to middle C whenever the gallery door is opened, i.e., it announces a moment of transition. To continue this genealogy of loss, one must turn to the opposite of cosmic light source, which is ancient darkness. “Dark Matter” is the term astronomers invented to describe invisible expanses between points of visibility—an enigmatic darkness, or in the words of E. E. Cummings, “the wonder that’s keeping stars apart.”26

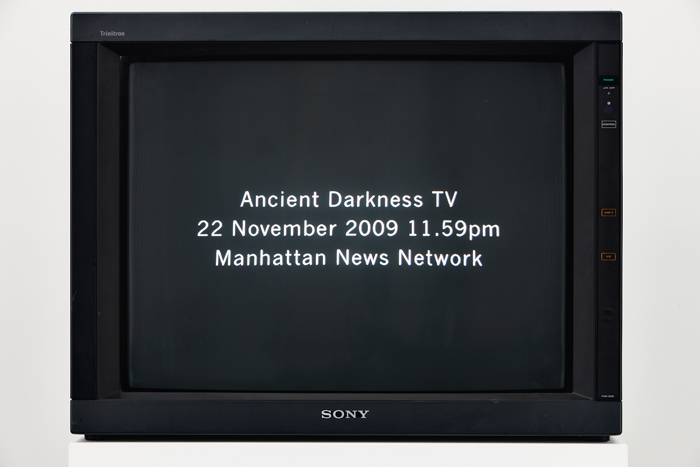

As one who has long been compiling a slide archive of darkness, it was natural for Katie Paterson to give us a wondrous media update to Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915). With the help of a television broadcast network and the astronomers at the Keck Observatory, in Mauna Kea, Paterson transmitted for one full minute the visual image of darkness from the furthest observable point of the universe, some 13.2 billion years ago, shortly after the Big Bang, and long before the Earth existed. Ancient Darkness TV (2009) is a six-minute-nine-second video recording of that television broadcast and is a perfect negative fulfillment of the Sky and Space Artists’ Manifesto.27 The new media version of Malevich’s Black Square is the transmission of darkness into the homes of contemporary Americans, thereby visually multiplying and proliferating the extremes of darkness in time and space. Indeed, the affirmation of the need for visibility of the invisible is ironically given art-historical roots in the 1968 Symposium organized by Seth Siegelaub. To Robert Barry’s proposition, “Nothing seems to me the most potent thing in the world,” Carl Andre responded with the statement, “I would say a thing is a hole in a thing it is not.” Andre’s observation was in turn used by Robert Smithson as the title of an article published later that year.28 Paterson’s Ancient Darkness TV is the Ur twenty-first-century cave painting, where the unlit cavity of the television monitor is the artwork. The color black is cleverly reinterpreted as the absence of light. And the color black has a “split identity” in the history of Modern art, “at once serving ultimate negation and the evacuation of meaning, and on the other being richly symbolic of inner and external worlds.”29

Katie Paterson, Ancient Darkness TV, 2009. TV broadcast, VHS transfer to DVD, 6 min. 9 sec. Installation view Haunch of Venison, London, 2012. Photo © Peter Mallet. Courtesy Haunch of Venison, London.

Katie Paterson exercises control over the anxieties we have about our extensive larger environment, communicating the invisible, the unseeable, and the mysterious. Paterson’s Ancient Darkness TV allows us to ask questions such as Jane Blocker raised in writing about Bruce Nauman’s corridor pieces: “What is the place of vision in works in which there is nothing in particular to see…, or in which seeing is frustrated…, or in which one is blinded…? And what is the function of representation in works in which nothing much seems to be represented?”30 Ancient Darkness TV absorbs our gaze and renews our capacity to receive light. If seeing triggers a cascade of reactions in our brain, what does not seeing do? The blinded viewer understands timelessness and infinity all the better when darkness is explored not as mainly ironic or dualistic or enigmatic, but as part of the primordial beginning and ultimate end common to life and art. On the other hand, a puzzled viewer may use that single minute to wonder about the blankness, may question if she is indeed viewing an emptied screen, and thus unexpectedly visualize and project her own subjectivities outward. One may quote again, “When I shut my eyes and look at darkness, even nothing becomes something: a star field, a fractal simulation, an indistinct halo. The fact of the real is another world from the figment of our imaginations.… Analogy satisfies our desire to place ourselves within the world—we link the known with the unknown to create an order that is dynamic and self-reflecting.”31 As Annushka Shani writes in describing other works examining darkness, it is “a void that is sometimes conceived as dreadful and nameless, a kind of mute otherness, beyond language and communication; or it might suggest a charged void replete with potential, a pause, an interval, a site for wonder and reflection.”32

To Otto Piene’s questions and concerns from 1973, “Why is there no art in space, why do we have no exhibitions in the sky? …Up to now we have left it up to war to light up the sky,” artists have answered with works in firecrackers, colored smoke, and light shows.33 However, Paterson goes the extra distance to set alight a Black Firework for Dark Skies at an unspecified location in 2010, and to display merely the ashen burnt firework in a box in the gallery. The event happened somewhere, remotely, like the death of the star. The smoke failed to communicate anything; the ashes index the event as past. It is as if the tattered firework remains are her miniaturized stand-ins for the explosions that heralded the star deaths. Indeed, the ultimate miniaturization occurs when the real is represented rather than figured. Paterson did just that for her 2011 Venice Biennale Project, 100 Billion Suns (2011), which involved a confetti cannon discharging 3216 pieces of paper with each explosion. Each colored circle apparently represents the colors of the various Gamma Ray Bursts, which are the brightest explosions in the universe, up to 100 billion times brighter than our sun’s. Paterson’s works are neither hopeful nor morbid, but transcend both states into an engagingly heady awareness of cosmic flux.

Both Leonard’s and Paterson’s works fold the wonder of the skies into Land art, by re-linking the body to the cosmic material. The massive is miniaturized to the scale of our body. We feel our bodies gazing and imbricated in Leonard’s sunlight. We feel the aging of our bodies in front of Paterson’s dying stars. Carl Sagan is proved right: We are all starstuff.34

Neha Choksi is an artist who lives and works in Los Angeles and Mumbai.