My place is the Placeless, my trace is the Traceless;

’Tis neither body nor soul, for I belong to the soul of the Beloved.

I have put duality away, I have seen that the two worlds are one;

One I seek, One I know, One I see, One I call.

—Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi

Standing in the center of Sherin Guirguis’s One I Call (2017), a modest SuperAdobe structure sited in Whitewater Preserve in California’s Coachella Valley, one noticed an absence of pigeons.1 This was not a strange observation to make considering that Guirguis patterned her sculpture after the pigeon towers that dot the countrysides of the Middle East and North Africa like giant tapered beehives made of earth and plaster. Everything about these pigeon towers has a purpose: the sticks thrusting out of the top are there to support anyone wishing to make repairs; the oculus in the roof allows birds to fly in and out; cubby holes where pigeons might roost are placed decoratively around the interior. But Guirguis’s sculpture breaks from the morphology of pigeon towers. First, where the towers’ purpose (dubbed “useful but unromantic” by one historian2) is to collect the birds’ droppings, which are used to add nitrogen to fields, their interior would normally be inaccessible save for these collection times. Yet here the artist has placed three large oval apertures at ground level leading into the interior of One I Call. Guirguis has also applied gold leaf to the inside of the roosts, a flourish missing from the pigeon towers of Iṣfahān or Siwa. Due to heavy rains in early 2017, this leafing wept down the inside walls, like the droppings of the animals so conspicuously absent.

Sherin Guirguis, One I Call, 2017. Earth, burlap, PVC pipe, barbed wire, gold leaf. In collaboration with Bob Dornberger, wHy Material Experts, Hooman Fazly, Don Worley. Whitewater Preserve, Whitewater, CA. © Sherin Guirguis. Courtesy the artist and Desert X. Photo: Lance Gerber.

Although the interior of One I Call is bare, its media and form are replete with history and meaning: medieval Persian poetry, the colonial history of the Middle East and North Africa, the utopic projections of lunar architecture, and the Western discourse of land art. It calls forth particular personages, from the Iranian-born earth architect Nader Khalili to the poet Rumi—while also marking the expansion of Guirguis’s politically oriented practice. In its form, materiality, and site-specificity, One I Call presents a useful counter to the imperial durabilities and neocolonial impulses of the large-scale art biennial that commissioned the work—Desert X (which ran from late February through April 2017). Instead, Guirguis’s sculpture asks viewers to become familiar with a history that references and acknowledges the politics of postcolonial critique.3 This essay attempts to take up this challenge, and so circles around the myriad histories opened up by One I Call, crisscrossing disciplines, geographies, and temporalities—before coming to roost upon it.

Sherin Guirguis, One I Call, 2017. Earth, burlap, PVC pipe, barbed wire, gold leaf. In collaboration with Bob Dornberger, wHy Material Experts, Hooman Fazly, Don Worley. Whitewater Preserve, Whitewater, CA. © Sherin Guirguis. Courtesy the artist and Desert X. Photo: Lance Gerber.

—

“The desert is god without man.” With this quotation, Neville Wakefield, curator and artistic director of Desert X, introduced the inaugural edition of the biennial across a variety of media platforms—web and print.4 The quote makes for good copy, but it is not sui generis; like the idea of the desert, it has a context. These words end a short story written by Honoré de Balzac, entitled “A Passion in the Desert” and published in 1830, the same year France invaded Algeria. Balzac’s story is a frame narrative in which a man relates to his beloved the tale of a French colonial soldier escaping capture. This soldier is subsequently cornered in a cave by a panther, whom the soldier must kill to escape. Filled with “tireless Arabs” and the “dark, forbidding sands of the desert,” the work is a textbook orientalist fantasy, wherein the dangers and erotic pleasures of Egypt are manifested in the figure of the blood-smeared panther, referred to as both an “enemy” and a “courtesan.”5 We find an echo of Balzac’s closing line in the infamous final words of Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness—“The Horror! The Horror!” Both represent a fantasy of the sublime inhumanity of the other place: there are no people in the desert, or, perhaps, the people who are there are more panther-like than human—shifty like sand.

It’s a predictable quote to begin any desert endeavor with, but a telling one, nonetheless. And so we must turn, perhaps just as predictably, to Orientalism, Edward Said’s signal study on the colonial literatures of France and Germany in the nineteenth century. Said notes, “The Arabian desert is thus considered to be a locale about which one can make statements regarding the past in exactly the same form (and with the same content) that one makes them regarding the present.”6 In other words, the desert’s mythology is that of timelessness and its character, at least in the colonial imagination, is that of an uninhabited and uninhabitable place. We might add to this Romantic fallacy the way that the desert is framed as a place of opportunity by virtue of its untapped mineral resources.7 Desert X’s publicity campaign traded on this understanding of land, ignoring or marginalizing any history of habitation by indigenous groups, preferring instead the mindset of the later settler colonialists travelling west, swayed by the imperatives of manifest destiny—land and gold.

Douglas Aitken’s Mirage (2017) became the emblematic project of Desert X.8 The piece was a purpose-built ranch-style house of which every surface—interior and exterior—was covered with mirrors. Mirage accelerated the already clichéd use of reflective surfaces endemic in public art projects since Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate (2004) opened in Chicago’s redeveloped Millennium Park.9 Indeed, Aitken’s structure was received as “A Funhouse Mirror for the Age of Social Media,” as one headline aptly put it, and was the most photographed artwork among Instagram posts tagged with the #desertx hashtag.10

Doug Aitken, Mirage, 2017. Acrylic mirrors, steel, plywood, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Desert X. Photo: Lance Gerber.

To reach Mirage, visitors drove through a security gate and up newly constructed roads for a speculative housing development called Desert Palisades, which was one of the major sponsors of Desert X. The development’s online promotional materials describe it, in high-colonial fashion, as “the last hillside enclave in Palm Springs.”11 In this imagining of an affluent neighborhood, homes “choreograph fluently with their surroundings,” buyers are encouraged to “enlist the world’s most prominent architects,” and the development as a whole “blend[s] with the landscape rather than reshape[s] it.”12 Aitken’s Mirage makes an appearance several times on the Desert Palisades website as a literal stand-in for the homes to be built there. While Desert X’s didactic materials acknowledge Mirage’s relationship to land development, describing it as a “latter-day version of manifest destiny,” I would deny that this amounts to a critical stance on the part of either the biennial or the artist. Rather, Mirage cynically reproduces the logic of land use, exploitation, and development intrinsic to manifest destiny. In this way, the surface of Mirage not only reflects the exterior landscape and the people moving in its interior, but also the class fantasies of the thousands of people who visited it—whether virtually through social media or directly in person.

In her 2016 book, Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times, anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler describes the reiterative character of postcolonialism—that is to say, colonialism’s continuing presence—via a sequence of Foucauldian genealogies. She asks: What have been the boundaries between camp and colony? How do concepts such as security, race, and truth mutate and come to mean differently in different eras? How have colonialist and imperialist formations rested on the enduring notions of states of exception? Duress is a key concept for Stoler, being “neither a thing nor an organizing principle so much as a relation to a condition, a pressure exerted, a troubled condition borne in the body, a force exercised on muscles and mind. It may bear no immediately visible sign or, alternatively, it may manifest in a weakened constitution and attenuated capacity to bear its weight. Duress is tethered to time but rarely in any predictable way.”13

We might therefore surmise duress and its lexical mutations—endurance, durability, and duration—as a performative language naming the tensions and flexions of colonial power and its linguistic post-conditional. And as the writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, points out, colonization is something that happens not only in the external world, but in the mind and imagination as well.14 Describing the places where these colonial presences are felt is a key component of Stoler’s project, as she productively pushes against the notion of colonialism’s “abstract ‘legacies,’” instead preferring to “make room for the complex ways in which people can inhabit enduring colonial conditions that are intimately interlaced with a ‘postcolonial condition’ that speaks in the language of rights, recognitions, and choices that enter and recede from the conditions of duress that shape the life worlds we differently inhabit.”15 But the potential pitfalls of such postcolonial projects are many. For example, one might only look for the places in which the colonial mimics the nation-state from which it sprang, rather than the other way around.16 Notions of internal/external—so important to a world order in which we are always home, and the other is always from elsewhere—would therefore be produced as stable and unconditional. Thus, we might want to invest some energy into thinking about the core difference between building a sculpture in the form of a three-bedroom house sited in the midst of an actual housing development, and building a home for pigeons on a nature preserve, a place protected (for the time being) from development.17

—

One way in which the architecture of everyday life can be reformatted is through acts of political dissent, which transitions a familiar place into a site of extraordinary significance and enduring cultural relevance. This process is alluded to in Guirguis’s 2013 series Passages // Torroq, which reproduce architectural details from Cairo’s main train station. Untitled (lahzet zaman), (Untitled [moment in time] ), is fashioned after one of the most prominent features of the station, the windows and clock of the corner tower. In making this work Guirguis cut intricate patterns similar to those appearing in the screens of the station’s many windows into large sheets of paper. She then used an air pump to blow a multitude of colored inks around the paper, forming organic, branching structures. These ink passages encrust the otherwise carefully reconstructed geometric ornamentation. The edges of these architectural details of Cairo’s train station, are leafed in gold, like the pigeon roosts in One I Call, and the fluorescent-colored backside of the paper emits a glow when floated off the wall or frame.

Sherin Guirguis, Untitled (lahzet zaman), 2013. Mixed media on hand-cut paper, 108 x 72 in. © Sherin Guirguis. Courtesy the artist.

These works are not just formal reiterations of a place; they also connect to the continuing political presence of Egyptian feminism. The Cairo train station is notable because, in 1922, it became the site where Huda Sha’rawi publicly removed her veil upon her return from the International Woman Suffrage Alliance conference in Rome. A year later, Sha’rawi founded the Egyptian Feminist Union. The act of Sha’rawi’s unveiling is often overinterpreted by Western feminists as an ur-feminist performance—a removal of the patriarchal structures that would otherwise cordon women’s bodies. In this interpretation, veiling is assumed to be the central sign of women’s oppression, standing for more structural inequalities such as access to education, limits on property ownership and finances, and familial piety.18 As Leila Ahmed notes, the veil is “fraught with ancient patriarchal meanings,” but at the same time, Ahmed grants that “it also serves as a banner and call for justice—and yes, even for women’s rights.”19 Most accounts of Sha’rawi’s unveiling fail to mention that she was already well known in nationalist and anti-colonialist movements. (Sha’rawi had organized an anti-British women’s rally in 1919.) She was also a widow. Both gave her greater social flexibility in public expression.20 More than an uncritical celebration of Sha’rawi’s act, Guirguis’s series renders in dichotomous geometric and organic forms—ruly and unruly—the ambiguity and ambivalence with which Sha’rawi’s act has been interpreted.

Two works in a parallel series, called Coops (also 2013)—Untitled (Noor El-Huda I) and Untitled (Noor El-Huda II)—stand out in this regard as well, and they arguably mark a transition from Passages // Torroq to One I Call. The cut-paper matrices in these works resemble both Egyptian pigeon towers and covered bodies. As such, these works speak to the presence of people, in particular veiled people—women—as vital and necessary as indigenous architectural forms. Here, the gold-leafing of the figure’s edge breaks out of its strict architectonic deployment, and bleeds to the paper’s border. The boundaries—between wall and window, between figure and ground—are called into question.

Like the Cairo train station, the pigeon tower is not without political significance in Egypt. Most noteworthy are the events of 1906, when a clutch of British soldiers in the village of Dinshawai found easy sport in shooting pigeons as they emerged from their towers. To defend their livelihood, villagers attacked the British troops; during the clash, a soldier shot and wounded a local woman. Another soldier, running back to camp from where the fighting was taking place, collapsed and died—most likely of a heart attack. The British Consul-General of Egypt used this as a convenient opportunity to quash growing Egyptian nationalism, executing four villagers and sentencing dozens more to life imprisonment, hard labor, and public torture.21

Pigeon towers also have a long history in Persia—and their feathered inhabitants were likewise the subject of colonial appetites. The number of pigeon towers increased during the Safavid Dynasty at the end of the sixteenth century, with the reign of Shāh Abbās, who was known as a great builder of infrastructure.22 When Thomas Herbert, a minor aristocrat traveling with a party of royal ambassadors from England (and thus welcomed into Abbās’s court), published the first English-language account of Persia, in 1634, he made note of the pigeon towers outside Iṣfahān.23 His observations were echoed by subsequent travelers, such as James Justinian Morier, who journeyed through Persia in the early nineteenth century and noted: “In the environs of the city to the westward, near the Zainderood, are many pigeon-houses, erected at a distance from habitations, for the sole purpose of collecting pigeons’ dung for manure… The Persians do not eat pigeons, although we found them well-flavoured.”24

To build her pigeon tower, Guirguis called upon the ingenuity of architect (and Rumi-translator) Nader Khalili. Born and raised in Tehran, and subsequently educated in Turkey and the United States, Khalili was an innovator in the realm of earth architecture. One I Call is made using Khalili’s SuperAdobe construction system, wherein burlap bags packed with an admixture of wet earth and stabilizers (such as lime or cement) are layered on top of one another, and the entire structure is covered with a mud and straw or lime plaster. For the project, Guirguis worked with a crew of the architect’s apprentices. (Khalili passed away in 2008.) This choice to reference Khalili through the sculpture’s production and materiality marks one of the primary ways in which One I Call diverges from the modus operandi of Desert X’s organizers.

—

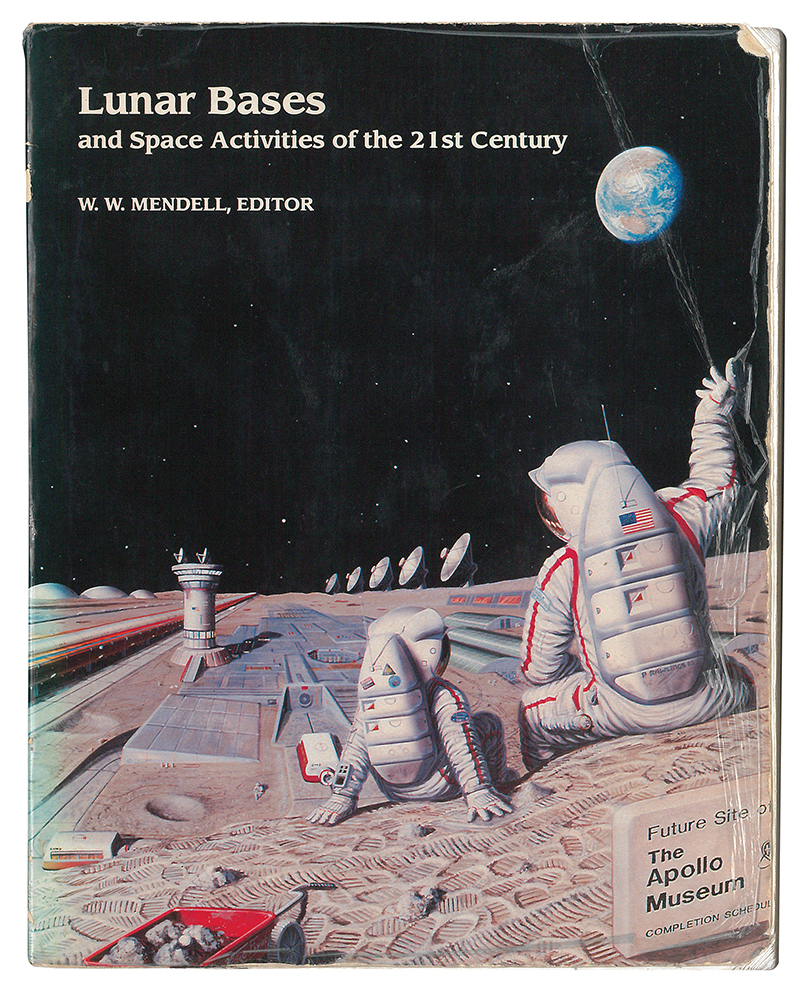

In a 1984 conference sponsored by NASA, entitled Lunar Bases and Space Activities of the 21st Century, the majority of presenters merely transferred the logics of mining, military base-building, and industrial materials onto the new landscape of the moon. As if to highlight the colonialist rhetoric on display in the presentations, the published volume of the conference proceedings closes with a Ben Bova science fiction story, “Address Given at a Tricentennial Celebration 4 July 2076, by Leonard Vincennes, Official Historian of Luna City,” in which the narrator compares the settling of the moon with “Columbus’ landings in America that actually awakened the Europeans to the fact that a whole new world existed on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.”25 The volume’s cover is aptly illustrated by Pat Rawlings, who describes his image, in part, thusly: “Two inhabitants of the Moon overlook an advanced lunar installation from a museum construction site.” These two inhabitants, an adult and a child (evidenced by the Radio Flyer wagon filled with moon rocks), are the speculative fruits of NASA’s Apollo missions, now memorialized in said museum. The cover fancifully compresses the central tenets of the colonial imagination and familial transmission. Following Stoler’s genealogical excavation of camps and colonies, it would be interesting to add bases and installations to the list of colonial concepts that continue to signify—not to mention museums.

Pat Rawlings, Two Inhabitants of the Moon overlook an advanced lunar installation from a museum construction site. The original, primitive lunar base lies to the left of a large electromagnetic launch facility, which dominates the vista. An array of solar dynamic generators on the horizon supplement the power from a nuclear reactor to operate greenhouses, industrial processing plants, scientific research laboratories, and a spaceport, 1985. Cover illustration for Lunar Bases and Space Activities of the 21st Century, edited by W. W. Mendell (Houston, TX: Lunar and Planetary Institute, 1985). © Pat Rawlings. Courtesy of Andy Campbell.

In contrast to his peers, Nader Khalili presented a paper at the same conference in which he elaborated his observations of adobe building techniques that he encountered in rural Iran. In that paper, “Magma, Ceramic, and Fused Adobe Structures Generated In-Situ,” his aim was to apply these centuries-old techniques to the lunar surface. Because of the lack of atmosphere and water on the moon’s surface (eliminating two of the four elements central to Khalili’s mystic notion of Yekta-i-Arkan, or unity of elements in architecture 26), Khalili proposed that focused sunlight could be used to heat and melt the lunar surface, creating shelter and roads. He also proposed a “giant potter’s wheel” for the “dynamic casting of ceramic and stoneware structures.”27 But his real breakthrough was surmising that housing could be built from the principles of earth architecture—dry-packing, corbelling, and leaning-arches.28 He counters the confabulist fantasies of his scientific colleagues with a proposal grounded in the indigenous building traditions of Persia—of which the pigeon tower is but one example. In characteristic style, Khalili spoke the academic language of his audience (“ceramic-glass and/or other lunar fluxes may be added to the main composite for lowering the melting temperature”), but also pushed them toward more plainspoken arguments for a responsive architecture made from lunar regolith: “Each person going to the moon, regardless of his or her work, must be aware of these fundamental [earth-architecture] principles and techniques to participate in creating an indigenous architecture to form their communities, not only because of economic benefit but also because of spiritual reward.”29

Khalili’s ideas, expounded upon five years later, in the Journal of Aerospace Engineering, was illustrated with a drawing of the “giant potter’s wheel” and mock-ups of shell structures. Also included was an architectural detail from the nineteenth-century Borujerdi House built by Ustad Ali Maryam in Kashan, Iran. This image is left strategically uncredited in the journal, and is accompanied instead by the caption: “Natural Lunar Contours Sculpted Using Magma Flows to Create Shielded Light Scoops and Radiation Vestibules.” In eliding the historical origin of the image, Khalili allows his audience to envision a future lunar architecture. Likewise, Khalili’s “Plan for Crater Base with Habitation and Workspace for 70 People,” a circular structure with radiating apses, shares much in common with the floor plans of Persian pigeon towers. In both instances, Khalili relies upon the visual and material culture of Persia without explicitly pointing to a place that was still aligned, in the minds of many US scientists, with religious fundamentalism and the hostage crisis at the US Embassy in Tehran.

It was Khalili’s hope that this lunar architecture would spur an interest in earth-architecture on Earth proper. As he remarks in his memoir, Sidewalks on the Moon: “To put it very simply, if I can prove that to build with soil or rock is valid on the moon, it will become valid on the earth. …It means they will once again seriously use and improve on earth as a material to create shelters for the homeless. …The Third World does not need to buy building systems, it needs to get a cleaning job on their brain-washed opinions.”30 In this respect, decolonization underlies Khalili’s revival and rearticulation of the vernacular building traditions of his homeland as filtered through the utopic imaginings of a lunar architecture. By making his work available to the galactic colonial ambitions of the United States, he hoped to accomplish something else altogether. This circuitous route towards solving some of the enduring concerns of global poverty evidences above all a resourceful rerouting of colonial logics.

Khalili could not afford to wait for others to catch on. In 1991, he founded the California Institute of Earth Art and Architecture (CalEarth) in Hesperia, California, an hour’s drive away from the Coachella Valley, site of Desert X. There he, his family, and his apprentices built prototypes of emergency housing, lunar and Martian shelters, communal meeting rooms, and, to prove to the American consumer that these techniques could result in a habitable first-world domain, a traditional three-bedroom, two-bathroom house (named, perhaps winkingly, Earth One), all utilizing his SuperAdobe system. In 1998, Khalili and his academic collaborator Madhu Thangavelu (conductor of the Space Concepts Studio at University of Southern California’s Viterbi School of Engineering) staged a series of photographs around the exterior of Mars One, a structure built on CalEarth’s land simulating what a lunar or Martian shelter might look like. In these images, Thangavelu, outfitted in a NASA space-suit, poses peering out of the window of the SuperAdobe domicile, looking as at home as the parent and child on the cover of the Lunar Bases book. Yet this speculative photoplay in San Bernadino County is an attempt to redirect the colonialist impulses displayed by the visuality of that book cover and the many papers contained therein. This brown spaceman, feet planted firmly on the ground, has brought lunar knowledge back to the galactopole, making a decolonial case for the work yet to be completed on Earth.

—

Guirguis’s One I Call operates similarly. Its presence among the sixteen projects commissioned by Desert X is unique in that it points to a history of building at once ancient and contemporary, and tied to the politics Khalili’s decolonial building practice. When it came time for the structure to be demolished, Guirguis insisted that the construction team, comprised of Khalili’s apprentices and the artist herself, demolish the structure. The hands that made One I Call were also the ones that unmade it, returning earth to earth. The sculpture’s temporal existence, unlike Aitken’s Mirage, won’t be replaced with a parody of mid-century modern design. Rather, it was there, and now it’s gone. The discourses of speculative development (one of colonialism’s favorite forms) ventriloquized and promoted in Aitken’s project are as likely to endure as any other colonialist project, but under these conditions of duress, those of us who seek a better world turn toward rethinking and reengaging with the past. In doing so, we make a far more durable home.31

Andy Campbell is Assistant Professor of Critical Studies at USC-Roski School of Art and

Design. He lives and works in Los Angeles.