Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.

—Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida1

Taryn Simon’s monumental text and photo installation A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I-XVIII is an extraordinary work: intellectually sophisticated, meticulously plotted, beautifully produced, poignant and excruciating in its details, and overwhelming in its cumulative effect. It is relentless in its pursuit of what we might call the presenting power of art. By that I mean art’s ability to make its stories present as aspects of a lived, historical world unbounded in its spatial and temporal extension, as well as carefully crafted features of a framed and bounded artifice.2 In that sense, the installation itself, as an entire enterprise, is nothing other than a serial instantiation of its own paradoxical (and literal) title. It is the expansive image of a living man declared dead (through art, by law, as history), whose death may yet be recuperated (also through art, by law, as history) and whose life, if not entirely restored, may at least be given a kind of provisional yet hauntingly powerful artistic presentness.

In many of its chapters, A Living Man Declared Dead is concerned with the issue of identity and the myriad ways through which it can be lost or effaced. It presents the stories, inter alia, of an Indian farmer declared legally dead thanks to judicial corruption; an Iranian man coerced to become the body double of Uday Hussein; “anonymous” victims of the Srebrenica Massacre identified by forensic science; a woman disguised by plastic surgery to facilitate her role as an airplane hijacker; an indigenous Filipino induced to appear as an anthropological exhibit at the 1904 Saint Louis World’s Fair; and a South Korean sailor kidnapped and “disappeared” by agents from the North. Likewise, we see any number of strategies through which lost or effaced identities can be restored or, depending on circumstance, forged anew.

Yet for all of its complexity, A Living Man Declared Dead is also in many ways a problematic work, deeply implicated in any number of contentious and contested issues related to the theorization of photography. In the worst possible case, it can be argued that the work intends to make itself visible as history in a way that is denied to photography simply by virtue of being what it is. Alternatively, it might be possible to read these historicizing claims more positively as pointing toward an important interpretive “pressure point,” a way of opening up a reading through applying stress to the structure of the work at a point of apparent weakness. Nevertheless, before engaging some of these theoretical and interpretive issues directly, it seems appropriate to work our way through one of Simon’s eighteen Chapters, as a way of teasing out exactly how meaning unfolds within the individual sections of the work.

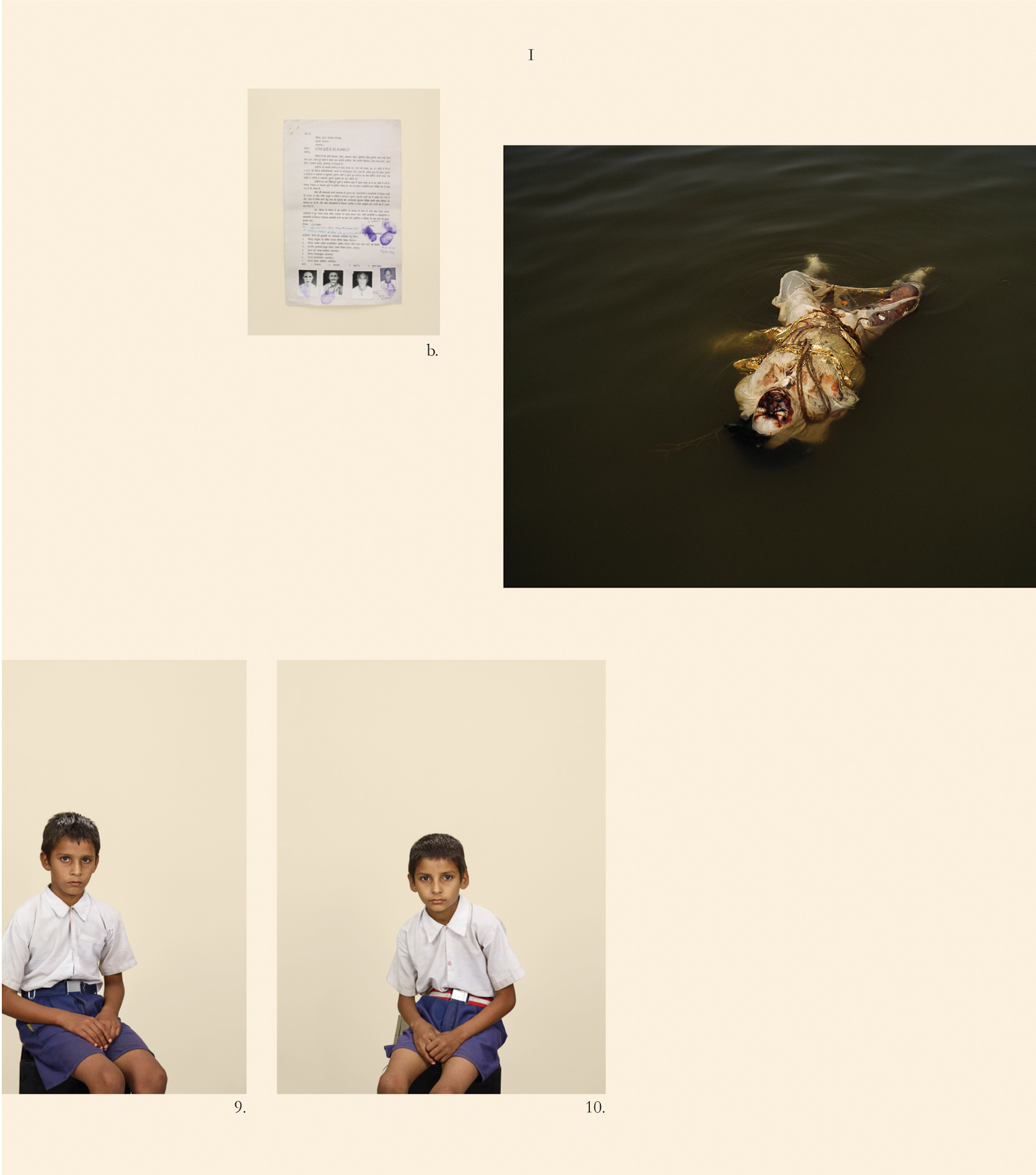

Taryn Simon, Excerpt from Chapter I, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII. 9. Yadav, Babloo, ~11/12 (birth date unknown). Student. Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India. 10. Yadav, Mukesh, ~10/11 (birth date unknown). Student. Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India. d. Corpse of a person with leprosy floating in the Ganges River. The dead are cremated on the banks of the river or tied to heavy stones and sunk in the water. Dhanaiy Yadav, Shivdutt Yadav’s father, was cremated along the banks and his ashes were scattered in the river. Ganges River, Varanasi. b. Letter to the chief judicial magistrate of Azamgarh demanding official recognition that Shivdutt, Chandrabhan, Phoolchand, and Ram Surat Yadav are living and maintain legal title to their land. The letter also requests that legal action be taken against all officers and family members who filed false information. Family file, Azamgarh. © 2012 Taryn Simon.

What better place to begin than with Chapter I, the case of Shivdutt Yadav, a farmer from Uttar Pradesh, India, and the living man of the work’s title, literally declared dead, thanks to a well-placed bribe, in the course of a dispute over the title to some ancestral farmland.3 Shivdutt is hardly alone in his ticklish existential situation. Not only are fraudulent declarations of death apparently common in Uttar Pradesh, where rising population and a complex system of inheritance have made intrafamilial competition for available land especially intense, but also two other Yadav brothers and a cousin have also seen their existences erased in the unfolding of this case that, thanks to bureaucratic and judicial incompetence and dishonesty, may well drag on for years.

Yet the “dead” Shivdutt is especially important, since, as the oldest of the three Yadav brothers, he forms the linchpin from which the all-important photographic “bloodline” descends as we move from a rather elliptical text to the rigorous grid of isolated photographic portraits.4 This ruthless pruning of the traditional family tree provides Simon with a perfect set of relationships to constitute the linear grid, the predominant formal ordering principle for the piece and the literal “picture of history” that we might imagine as its intended object.

In his introduction to the catalog presentation of the work, the Harvard professor and post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabha describes this bloodline as the embodiment of an “ineluctable order” endowed with a “blind authority,” itself challenged by the “random and contingent events, accidents and violence” of everyday life here represented in Simon’s so-called footnote photographs, which appear in the exhibition to the right of the narrative texts that separate them from the bloodline photos.5With all due respect, this does not seem to me to be a sustainable analysis. The “sanguine seriality” of the bloodline does indeed give the appearance of a rigid linear order, but that order is clearly an artifact of the photographer’s decision to provide precisely that appearance.

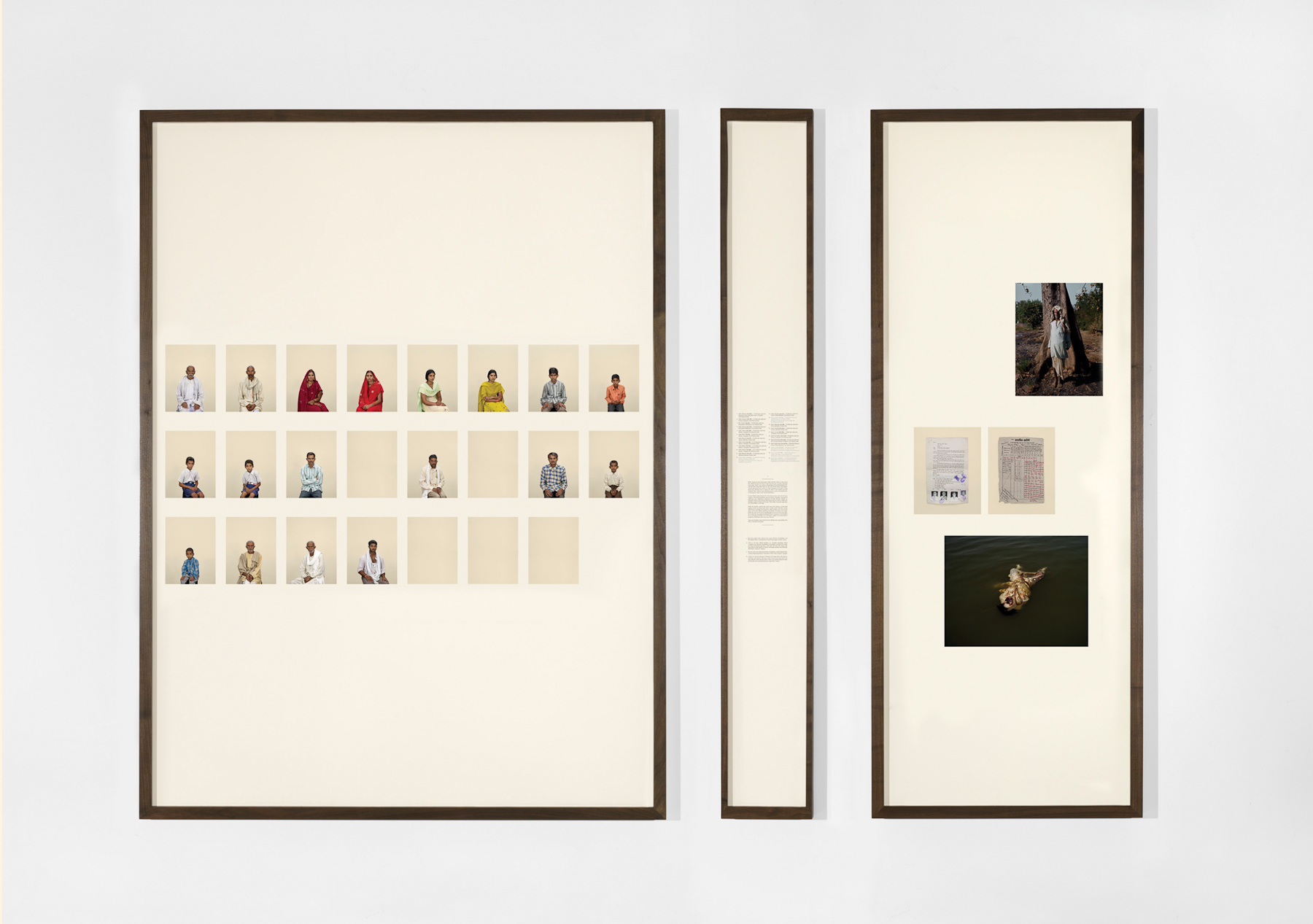

As presented by Simon in the catalog,6 Shivdutt’s story is first given a brief narrative form in the introductory text, which provides an overview of the case as well as a modicum of contextual material. The text is information rich,7 but open ended (perhaps necessarily so since the case was unresolved at the time of its composition) and in some important ways incomplete—for example, it fails to provide much information about the “other living heirs”8 of Yadav’s father, whose machinations are the cause of the brothers’ difficulties. On the other hand, the bloodline photographs to which the text introduces us are information poor, and making any specific narrative sense of them depends finally on the identifying information provided in their captions. But they do perform one quite specific job, at least in relation to the introductory text. They confirm our suspicion that the aggressors in the inheritance case are at once heirs of Shivdutt’s father and yet not members of Shivdutt’s bloodline; in short, that they are relations from the maternal side of his family.9 This insight into laws or customs governing inheritance in Uttar Pradesh does not solve all our interpretive problems with respect to the text, but it does importantly enrich our understanding of the familial dynamics that underlie it.

Taryn Simon, Chapter I, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII. © 2012 Taryn Simon.

Of the four so-called footnote photographs, the first literally fills out our picture of the four related living dead men; the last, which shows the body of a dead leprosy victim floating in the Ganges River, serves no evident purpose.10The middle two are both central to the plot of this particular story and key to our understanding of the place of photography within the problematic of this narrative, and of the project as a whole. The first of these (labeled “b.”) is a photograph of a document submitted to the Azamgarh magistracy demanding the reinstatement of the three Yadav brothers and their cousin to the ranks of the living. This plea is supported by snapshots of the four “dead” men along with what (I assume) are thumbprints. The second (“c.”), which appears to predate the first in terms of narrative sequence, captures photographically the fraudulent land record asserting the Yadavs’ deaths and deeding the contested land to the appropriating cousins. This looks to be a printed official form, filled in and annotated in red and black ink, and comprises a purely textual record.

What exactly do these two photos tell us about the “history” to which they bear witness? That text (necessarily) trumps image? That seeing is not necessarily believing? That ink is thicker than blood? Indeed, but perhaps first of all that a “living man declared dead” is not necessarily all that different from a living man under sentence of death, in this case Lewis Payne, the condemned would-be assassin of Secretary of State W. H. Seward, whose pre-execution portrait photo was made famous by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida.11 Like the photograph of Payne, the photos of Shivdutt and his relatives attached to their existential attestation are, by their very nature, images abstracted from the stream of time.12 In short, they cannot tell us, or (more importantly) the Azamgarh magistrate, anything about the state of things in the now attested by the document. And, in more theoretical terms, that means that they cannot of themselves constitute a history.13

Taryn Simon, Excerpt from Chapter VI, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII. © 2012 Taryn Simon.

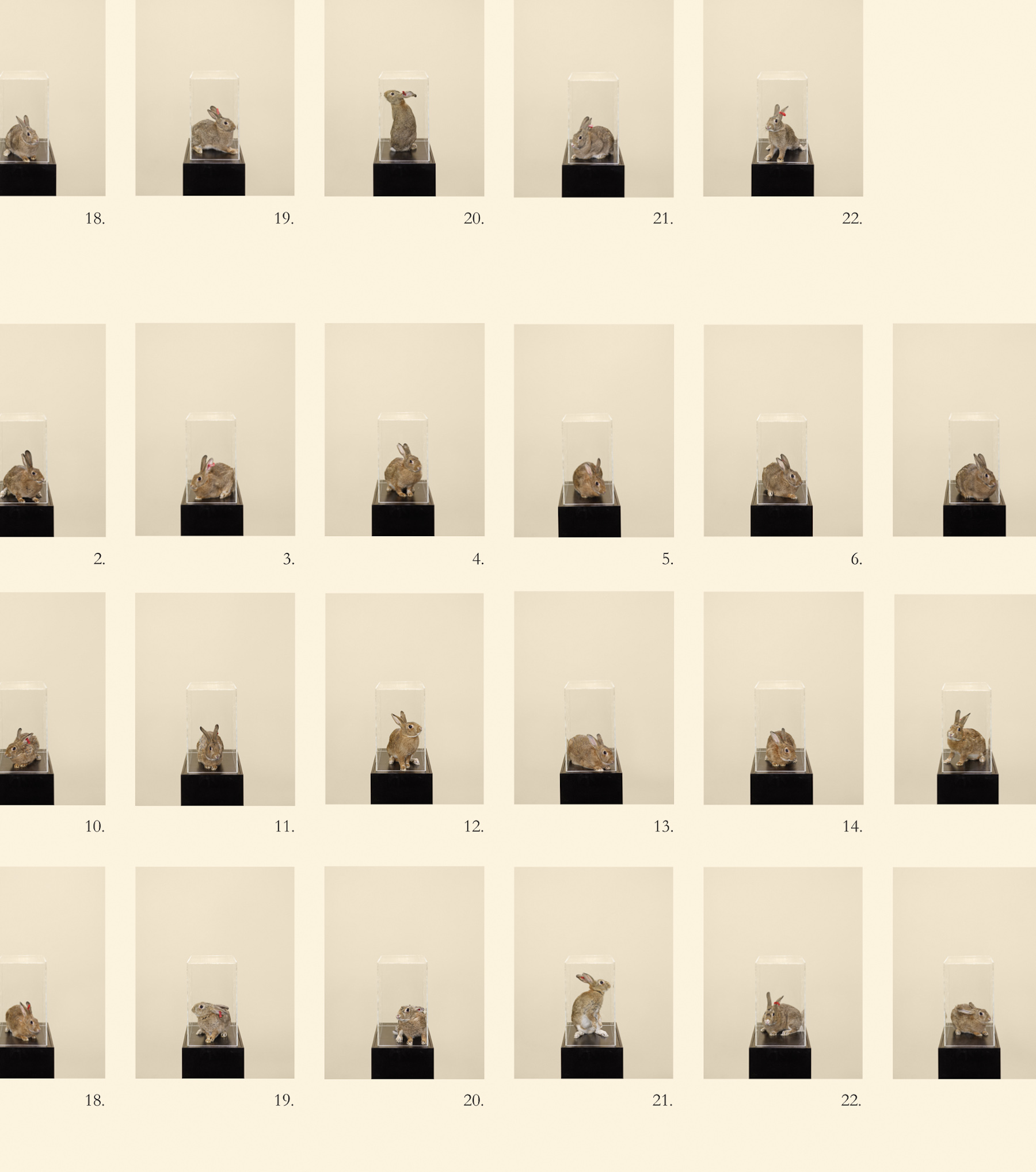

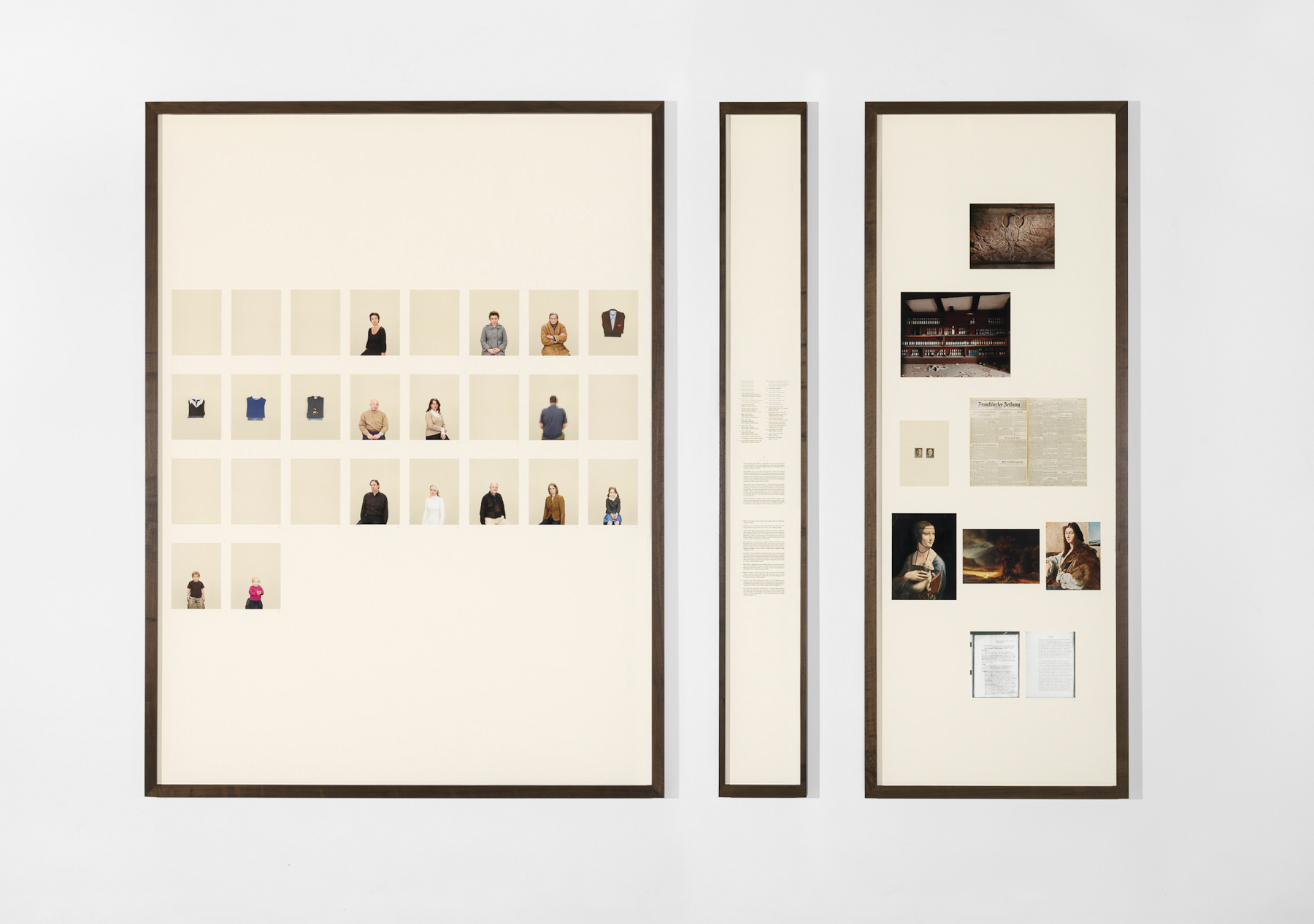

This brings us, at last, to a consideration of all of Simon’s sequential grids of bloodline portraits that, in the museum installation, occupy the opening panels of each of her eighteen chapters. All photographs can make those absent appear in some sense as if present, but they cannot provide evidence for the living immediacy of that presence since the images are inevitably and ineluctably indexed to the moment of their making, a moment that perforce exists as time past. Considered as a general class of pictures, Simon’s portraits constitute an amazing gallery of uncanny (unheimlich, in the Freudian sense) images. Although they conform to the simplest formal conventions that bind “high art” portraits as they have been produced since the Renaissance to millions upon millions of amateur snaps, Simon’s portraits almost universally present a relentless lethargy and ill-at-ease-ness, an interior blankness, an existential reserve (not to say void) that I eventually found quite disconcerting. (Conversely, I found the taxidermied rabbits of Chapter VI in their vitrines to be by far the “liveliest” of Simon’s subjects.) Against this blankness within any given bloodline, it is possible, in a way no less disconcerting, to watch the play of physical similarity and difference, of resemblance and its absence as it washes across the generations like breaking waves washing across the sand. But the effect of this analytical registry never constitutes the embodied experience of lived history.

And this, I think, is the point where we come to experience the maximum tension within the project as a whole. The seriality of the portraits always struggles to constitute itself as history, but is only an unfolding temporal narrative rigorously controlled by the transmission of the genetic code, or, in the most poignant case (Chapter VIII: the thalidomide triplets born to Dorothy Gallagher), through the eventual transmission of its distorted fragments.14 From a theoretical perspective, we can understand this failure as a result of what Michael S. Roth has termed “photography’s inability to conceive duration.”15 As Roth cogently argues in his discussion of Michel Frizot’s observations on photography’s power of attestation: “Photographic power is the power of segmentation,” the power of capturing the imperceptible instant, which thereby defeats both the idea of duration and the operation of memory.16 Without memory and without duration, there can be no history, only the mechanical trace of a catastrophe (whether a life or a death) that is always already both present as image and absent as event, forever fixed and never lived. But things, I think, are not quite this simple.

In the first place, if we turn from theorizing about the work to actually looking at the work, we encounter all these complexities in a way that seems appropriate to our earlier invocation of the word struggle. The unfolding of the bloodline is really (at least in many of Simon’s cases) a recapitulated cascade of events (the sequential birth of individual offspring, the reiterated passage from generation to generation17) that makes up a fragment of a genetically constituted family history. Indeed, on a superficial inspection, the serial portraits might easily be said to “look like history,” in a kind of under-theorized or seat-of-the-pants way. When we focus our attention on a specific series, taking the images one by one, this incipient narrative is irreparably fragmented. On the one hand, the individual images, as uniform units in the series or grid, retreat into an abstract world of Minimalist repetition. On the other, as portraits, they seem to comprise the nominally replicative members of a genre or type: police mug shots or high school class pictures. Nevertheless, they assert (despite all structural, formal, and familial resemblances) an aggressive, or perhaps better a passive/aggressive, individuality. We can see this even in pairs of most closely related sitters: Shivdutt Yadav and his son Nageena, or Shivdutt’s daughters, the sisters Gayanti Devi (married to an absent husband off the bloodline) and Suneeta Yadav.18 Each portrait offers itself up as an object of study, contemplation, and reflection. Despite, perhaps even because of, the sitters’ apparent lack of affect, their ability to meet our gaze without acknowledging our existence, their obvious confinement within the rectangle of an image which comprises a fictive world virtually flat and inarticulate, every detail of dress, every nuance of pose, every trace of individual presence (whether exultant or abject) becomes significant as a momentary irruption into the putative flow of history. Thus it becomes not so much a case of individual existences within the fictive history of the bloodline being impacted by the accidents and contingencies of everyday life, but rather of their photographic “catastrophes” exploding the continuity of a history implicit in the serial grids. Finally, these grids of contentious individuals fail to “translate” the narrative embedded in the texts.

Taryn Simon, Chapter XI, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII. © 2012 Taryn Simon.

This is not to say that the subjects of the portraits are unaffected by the histories reported in those texts. The stories themselves are unfailingly engaging, occasionally gripping, and often just a bit eccentric. The relatives of Shivdutt Yadav and his brothers, for example, must feel a daily and substantial impact from the denial of access to the arable land under dispute. But their sense of loss must be quite different from that of the relatives of Choe Janggeun, the South Korean sailor abducted in 1977 by agents from North Korea (Chapter V, p. 165ff); and that sense of loss is in turn different from the guilt, anger, fear, etc. (the range of potential emotions or reactions here is hard to specify) of the living descendants of Hans Frank, Hitler’s personal legal advisor, lawyer to the Nazi Party, governor-general of occupied Poland, and executed war criminal deeply implicated as an agent of the Holocaust (Chapter XI, p. 425 ff). The experimental rabbits (Chapter VI, p. 181ff) of course felt none of this, although their fate in the wake of an accidental event, the acquisition of their bloodline ancestor by the Robert Wicks Pest Animal Research Centre in West Queensland, Australia, was easily the most extreme of that chronicled in any of the stories: 100% mortality as subjects in tests involving RHDV (rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus).19 Their blissful ignorance is delightfully if morbidly expressed in the liveliness and evident curiosity of the mounted specimens confined to their vitrines. Perhaps most interesting is the case of the indigenous Filipino Cabrera Antero, who was brought to the United States in 1904 to be displayed as part of a living anthropological museum at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis.20 Despite the evidence of an already complicated set of colonial cultural intrusions, embodied both in Cabrera’s Spanish name and in his attested ability as an English speaker, Cabrera was packed off to Saint Louis as a representative of the indigenous Igorot people, “known” for their head-hunting expeditions (recorded in elaborate tattoos) as well as their ritual consumption of dog meat, which, extracted from its ritual context and re-presented in a way that seems roughly equivalent to feeding time in the lion house, became one of the “ big hits” of the whole exposition.21

Since, for reasons unknown or unreported, Cabrera elected to remain in the United States at the close of the exposition, his bloodline experienced a major bifurcation, cascading toward the present along Filipino and American branches. Indeed, his descendants are now established in Guam, England, Australia, and Canada, as well as in numerous cities and towns across the Philippines and the United States. Descendent outliers also appear in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Vietnam. The ethnicities apparent in the portraits cover such a considerable range as to pose a question about conventional definitions of family, ethnicity, and race. This is a literally globalized family, a situation perhaps best embodied by the final two sitters in the series: the siblings Elizabeth Shizue Dirige (born March 25, 2005) and Claude Abraham Dirige (born December 22, 2006) from Bontoc, the Philippines, the original Igorot homeland.22 One of the two, Claude Abraham gazes warily out of his portrait wearing only an elaborate loincloth in a brightly woven and very colorful design that must be intended to evoke the traditional culture of the Bontoc Igorot, a return to cultural if not ethnic roots.23 His slightly older sister, who also seems a bit wary of the photographer’s presence, proclaims her cultural allegiance rather differently: she wears a short denim skirt, pink sun-glasses and a pink-and-white Material Girl girl top: a westernized Madonna to her brother’s traditional warrior.

Taryn Simon, Excerpt from Chapter VI, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII. a. Haigh’s chocolate Easter Bilby replaced Haigh’s Easter Bunny in 1993. Haigh’s stopped making chocolate bunnies and joined forces with the Foundation for Rabbit-Free Australia in an effort to counter the annual celebration of rabbits. Product of Haigh’s Chocolates, Adelaide. b. Rabbits killed with .22 Magnum rifles by NatureCall, an organization hired to eliminate rabbits from private properties. Dead rabbits are laid out to record data, including sex, age, pregnancy, and active virus status. Cattle-grazing property west of Kingaroy, Queensland. © 2012 Taryn Simon.

As should be evident by now, I do not consider A Living Man Declared Dead to be a totally successful work. This is due, in part, to the way in which the photographic artifact has been theorized, especially in relation to the registration of duration and the structure of historical narrative, bolstered by my own experience of the specific photographs that are the major components of A Living Man Declared Dead. Photography’s power of attestation, its apparent ability either to witness on its own account, or to make of its viewers “virtual witnesses,”24 should make it a powerful tool for the construction of historical narrative or, invoking a slightly different vocabulary, for the archival preservation of an externalized cultural or historical memory. However, its ontological inability to register duration, its virtual fetishization of “the moment,” functions rather to disrupt history, to explode memory into incoherent fragments, to dissolve causal sequence into mere seriality. Against this theoretical critique, I can pose my own experience of these particular photographs. In one sense, I might simply affirm the substance of the theoretical critique, since A Living Man Declared Dead beautifully exemplifies the problems inherent in that analysis, so much so that it’s hard to escape the possibility that the artist has simply misconstrued the nature of her medium. But this seems to me unlikely, and in any case shortchanges my own experience.

What seems much more likely to me is that A Living Man Declared Dead represents a conscious attempt to move beyond the structure of a project like Simon’s earlier staged portraits of the wrongfully convicted, The Innocents25 (2002) with its narrative balance between text and image (one story: one photo) and its photographs that at least occasionally push the boundary of melodrama.26 In The Innocents, the idea was to show how photographs can be manipulated contextually to constitute a false history—although in that case Simon’s text seems to imply that she is in fact concerned with the (ontological) unreliability of photographs, not about how cops and prosecutors can misuse them to get a conviction—an ability that indeed depends on their having a sort of “aura” of indexicality: photos don’t lie, liars lie using photos. Here, on the other hand, the assumption seems to be that photos can in fact be used to establish truth claims about the effects of events on people, that is: about how they exist as actors within histories. Her choices in A Living Man Declared Dead strip the photographic portraits as clean as possible, control the choice of subject and the process of production as rigorously as possible, multiply their number and sequence their arrangement, and thus attempt to seize the narrative high ground, the ground of history, by the sheer dint of struggle. Indeed, theory aside, it is hard not to feel that sense of struggle, of straining after what is eventually an impossibility as one works one’s way through the stories one after another, through all the structural changes, all the permutations of and exceptions to, the ironclad rule of the bloodline. It is indeed an extraordinary attempt, and one that needs to be made, since theory, after all, is (or should be) grounded in practice, and not the other way around. If A Living Man Declared Dead is not in the last analysis quite theoretically successful, that strikes me as placing no onus on the artist. Rather, at least in this case, it marks her out as someone willing to articulate a practice according to her own lights, and theory will either come along, or it won’t.

In addition, it seems impossible to overstate the individual and cumulative power of the bloodline portraits themselves. If it is sometimes unclear exactly how the subjects portrayed have been buffeted by the accidents and contingencies of the event personified by the linchpin of the bloodline sequence, it is never unclear that these are buffeted people. Innocence is a characteristic very soon swept away by the world.27 It devolves quickly into wariness, defensiveness, a skittish curiosity, a sullen, brooding anger, a physical and an existential weariness, a deep and profound suffering, perhaps a barely perceptible hope or joy. These folks are representatives of a literally worldwide community whose Avatar is not so much a Renaissance portrait by Raphael or Titian, but a fifteenth-century north European Christ crowned with thorns. They evoke empathy, perhaps in some cases compassion; even the empty spaces in the sequences are resonant. In short, in the power of their combined presentness they seem to encompass and transcend their being as a unrealized history or fragmentary photo archive to attain existence as a kind of magnified Greek chorus demanding “not gratitude for our victories, but the recollection of our defeats.”28 If only it were possible for us to recollect them.

Glenn Harcourt received a PhD in the History of Art from the University of California, Berkeley. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles.