The truth of the matter is that you always know the right thing to do. The hard part is doing it.

—General Herbert Norman SchwarzkopfThe only adequate war memorial would be peace. —Ehren Tool

The exhibition title Production or Destruction quotes a Navy propaganda poster from World War II.1 The slogan’s pithy message is clear: our nation’s survival depends on what we make. While he agrees the stakes are life and death, ceramicist and Gulf War veteran Ehren Tool changes the nature of that production. He makes cups by the thousands, battalions of them. Each is formed by hand, stamped and stenciled with slogans and insignias—military and antiwar, death, protest—ringed with a sandbag pattern, and glazed with the colors of combat. After five years in the Marine Corps, including deployment in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, Tool earned his MFA at the University of California, Berkeley, identified as an artist, and since then has made over 14,000 of these cups. Nearly all have been given away. Tool wants you to have one. There are many like it, but this one is yours.

Ehren Tool, Cup for Fred, 2012. Stoneware with ceramic decals, 4 × 4 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Stoneware cups covered two full walls of the gallery; their surfaces were decorated with everything from bald eagles to Guy Fawkes masks, oil drums, bombs, skulls and crossbones, the seal of the President of the United States, burned corpses dangling from a bridge, Kissinger on the phone, Cronkite in a GI helmet, the Death tarot, Osama bin Laden, the words “Rest in Peace,” George W. Bush visiting a scarred soldier, porn actresses draped with the Stars and Stripes, portraits of soldiers in dress uniform, a black chess pawn, and a hole leaking red glaze. The details can be misleading. They are seductive yet jarring; their earnestness looks like irony. Family portraits clang against psychotic Mickey Mouse heads. One cup is stoic and elegant, funereal in its depiction of war; its neighbor is deflated and cracked. But ain’t that America? Don’t these contradictions melt into the ambiguous patriotic wasteland of one common culture?

Other works in this exhibition at the Craft and Folk Art Museum (CAFAM) include a “platoon” of twenty-five unglazed stoneware cups made from local clay in Biên Hòa, Vietnam—some decorated with the hexacomb motif of Agent Orange. Four porcelain cups, Porcelain Fireteam (2012), sit backlit and glowing on a black shelf; their surfaces are stenciled with formal military portraits. One wall presents red, white, and blue cups in the form of the American flag. And on the floor in the center of the gallery is 393 (2004), an array of shattered black cups— one for each combat death from the first year of the Second Gulf War, smooth inside, raw outside, gridded like grave markers. These cups have been shot with a pellet gun, one by one, and nearly all exploded. Nearby, highspeed photographs of breaking cups only point out the fragility of these objects while stripping them of their paradox, which is their precarious place between eternity and waste.

Ehren Tool, 393 (detail), 2004. Stoneware with ceramic decals, dimensions variable. Courtesy the Craft and Folk Art Museum. Photo: Noel Bass.

Fired ceramics can last for thousands of years, yet an instant separates a cup from shards. An instant separates a soldier—a father or mother, a son or daughter, a friend—from a body. Tool’s vessels, once broken, are no longer cups, barely metaphors, dust to dust. Indeed, a quasi-Christian mysticism animates these objects, like Saint Sebastians pierced by Tomahawk missiles or shrapnel. In another sense, the cups proffer cliché anti-war sentiment with the profundity of bumper stickers—overly sentimental, simply ironic, or in bad faith. They are more, but the viewer must first meet Tool’s gesture with equal generosity. The cups occupy an uncomfortable middle ground that implicates the military in the civilian and the civilian in the military, ultimately asking that we all share the burden of our nation’s wars.

+

In his 1991 essay “War Without Bodies,” Allan Sekula dissects the groomed image of General H. Norman Schwarzkopf (Tool’s ultimate commander in the First Gulf War) as a warrior retrofitted with sensitivity: an androgynous yet decisive hero able to sweep aside Vietnam Syndrome as deftly as he repelled Saddam Hussein. The General keeps T. E. Lawrence on his bedside table, loves Classical and country music, is a member of Mensa, enjoys wearing Arabian robes—in short, is “feminized” to a degree that lends him complete understanding of peace and domesticity.2 Yet his active participation in conflicts from Vietnam to Grenada to the Persian Gulf also provides a privileged grasp on the complex realities of battle. When faced with the unrelenting ire of Peg Mullen, the mother of a soldier killed in Vietnam by friendly fire while under a young Schwarzkopf’s command, the then-Lieutenant Colonel treated Mullen with patronizing empathy.3 While he shared her grief, he had also been a soldier; he knew what she could not possibly know. True to his hyper-civilized pose, the general demanded hysteria give way to reason. Tool is a parallel figure: a generous and sharp-witted potter in a camouflage apron who calls himself the “kiln bitch” of UC Berkeley; the ex-Marine who weeps with strangers, who loves the warfighter but detests war, and who makes art.4 And not just any art, but one both sturdy and penetrable. Ceramics, housewares, crafts in general are considered part of a domestic and feminized sphere supposedly antithetical to the masculine world of war. Tool’s cups slip into the civilian world with ease, but, decorated with emblems of destruction, they do not entirely disappear. Tool the artist is a craftsman-philosopher akin to the warrior-statesman of Schwarzkopf. Yet he turns the mobility of such a persona toward peace. He has done his duty, he has seen war, he has experienced its alien and masculine rationales—and he got out when he could, requesting posts guarding United States embassies in Paris and Rome. Now, from the realm of craft, emotional and artistic, he deploys his cups.5

Ehren Tool, Ehren Tool: Production or Destruction (installation view), 2012. Courtesy the Craft and Folk Art Museum. Photo: Noel Bass.

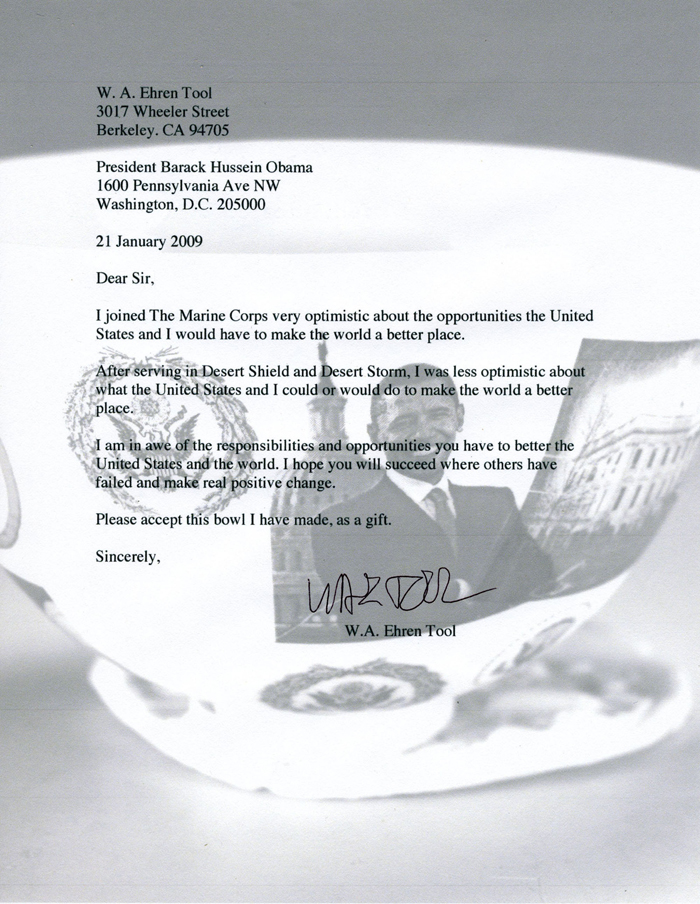

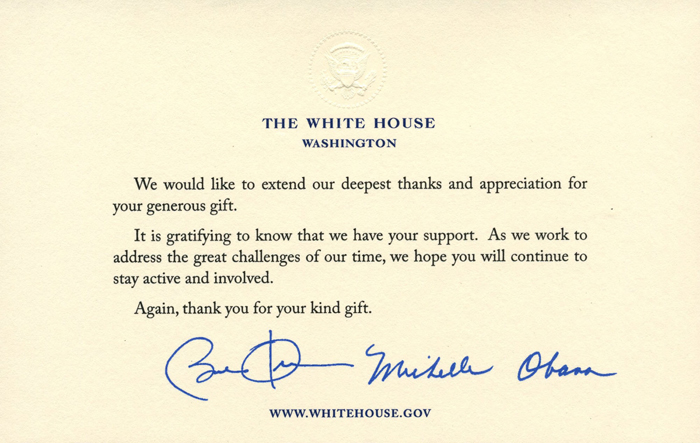

Those who have seen combat up close don’t need atrocities painted on a cup to remind them of the cost of war. Says Tool, “The nasty cups are for the rest of us.”6 In 2001, as war in the Middle East again seemed imminent, Tool mailed a cup and a letter to each member of the United Nations Security Council, urging them to choose peace. China refused the package; many others went unacknowledged; but a few replied. A Tool cup reportedly sat on the desk of the United Kingdom ambassador to the UN, and another was beside the Secretary of the Navy’s sign-in sheet at the Pentagon.7 In all, he has sent dozens of cups and letters to government officials and other public individuals across the globe. The CAFAM exhibition includes three such letters and their responses, along with photos of the pieces. Riley Bechtel, CEO of a construction firm that received huge infrastructure contracts in Iraq, thanks Tool for appreciating his company’s work for the people of that nation. Donald Rumsfeld thanks Tool for the mug and for his service. The Obamas sent a signed form letter.8 In this correspondence, the cups and bowls “inflict”—in the doubleedged way of the gift—if not a proximity to the front lines then at least a proximity to the lives war shatters. The cups sent to these powerful men and women are stand-ins for Tool, a soldier, putting a face to a number. In what Sekula calls a war without bodies, Tool’s cups become the bodies.

Ehren Tool, Letter to Obama, 2008. Letter. Courtesy the artist.

Ehren Tool, Bowl to Obama, 2008. Photograph. Courtesy the artist.

Ehren Tool, Letter from Obama, 2008. Letter. Courtesy the artist.

Tool has no commercial gallery representation; his work is often first encountered in a museum setting such as CAFAM. Cups given away there or at one of his lectures or studio residencies can be used and handled; they hold coffee and bourbon and water, and as you drink, you will remember war. The cups are unique but not priceless—they are gifts from Tool. More than images of war, more than fine-art objects we are reticent to touch, the cups, intimate and corporeal, are absorbed by the home. A binary between craft and fine art in some way corresponds to the division of the domestic and the military. Yet we might conclude that this division is not only artificial—it is upheld and reinforced by the myths of art and war alike. Tool’s interlacing of the feminine-domestic with the masculine-militaristic allows his work to inhabit both spheres—as do we.

This conclusion is not self-evident, or is at least ugly enough to inspire denial— to the extent that, in 2004, Martha Rosler found it necessary to reprise her classic collage works from the early 1970s, Bringing the War Home (House Beautiful)—this time with a bombed-out Iraq rather than Vietnam viewed out the windows of impeccable suburbia. The housewife with her vacuum became a model with a smartphone, reframing consumer culture as the home front and us as the aggressors—as do the bloodied-dollar designs on some of Tool’s cups. Rosler’s original series first appeared at an intimate scale in underground publications and as photocopied leaflets. But even before their thorough canonization, Rosler’s collages maintained a critical distance, tweaking the ploys of media far from the glossy pages of House Beautiful. Meanwhile, ceramics has remained largely consigned to the status of housewares. The ambiguous pedigree of Tool’s objects suggests his chosen medium has not entirely lost its feminine gloss. In part, this Schwarzkopfian image, refitted for pacifism, allows Tool’s pieces to infiltrate the domestic—to “bring the war home.”9

+

Since the Soviet invasion of 1979, Afghani rug makers—chiefly women—have incorporated tanks, planes, grenades, assault rifles, bombs, and other armaments as motifs among the flowers and other patterns. Today these socalled Afghan war rugs are mostly a tourist trade, directed at Westerners for whom the Afghan conflicts are a distant reality. Yet the rugs were at some point intended for use in Afghani homes. Their Western buyers often display the rugs on their floors. The rugs have much in common with Tool’s cups, in that they blend the imagery of war with traditional crafts that then occupy the domestic sphere, serving as constant reminders of war. That their weavers have witnessed conflict first-hand only adds to their authority. In the United States, our leaders must account for their military service, or lack thereof: Clinton’s draft-dodging, the John Kerry “Swift Boat scandal,” Kennedy shirtless in the Pacific Theater, George W. Bush’s questionable Air Force record, and so on. We hold our “war artists” to a softer but comparable standard. Trevor Paglen’s blurry, illegible telephoto images of military “black sites,” for example, rely on an indexical proximity to actual defense installations. For better or worse, Tool’s cups find recourse in their maker’s “having been there.” Fellow veterans have accused Tool of impersonating a soldier. He is proud to correct them.10 Sekula, Rosler, and Paglen aren’t veterans. For that matter, neither is Obama. Tool is.11 But rather than remain aloof towards the uninitiated, Tool wants to show us war—not in the spectacularized fashion of photojournalism, movies, or video games, but in an intimate way, through a dispersed monument, a memorial to an unknown soldier. Tool extends to his audience the privilege of the witness—if not to battle, then to the internalized atrocities of a nation geared for war. On these terms, Sekula was raised in a struggling aerospaceindustry household; Rosler’s kitchen is a battleground of a different sort, where internalized consumerism fuels imperialist aggression; Paglen, albeit cynically, reiterates the obscure distance from which most citizens view the military. Tool’s cups allow that not only the Schwarzkopfs of the world are capable of knowing loss—nor are they alone in bearing responsibility. By extension, it is every citizen’s right to speak about war.

The efficacy of Tool’s cups lies not in their wit or overwrought sentiment but in their persistence—even as they are abstractions of war’s irreducible price (and even as the Pentagon strives to eliminate that price, at least for the United States, through robotics and special ops). As the cups fan out, Tool’s hand-to-hand community grows. Over ten thousand war cups are at large and embedded in the world—in the homes and offices and studios of heads of state, CEOs, artists, and other folks. Tool’s audience forms through chance encounters as much as through deliberate visits to museums. The cups constitute a new folk art akin to Afghan war rugs, or to the elaborate beer steins of Germany, which incorporate images of battle into a full-spectrum cultural mythos. America lacks a contemporary war monument at this scale. And so, Tool sets out to remind us of war simply— contradicting spectacular visions of bodiless combat with a metaphorical campaign of his own.

Travis Diehl lives in Los Angeles. He edits the arts journal Prism of Reality.