Traveling during the Thanksgiving holiday period, the main topic of conversation amongst my fellow travelers seemed to be about going home. As a “resident alien,” it made me feel curiously homeless, a kind of stranded ET, and when I stepped on board the plane and the attendant asked me if I was on my way home, I was stumped for a second. Not only was I not going home, but it occurred to me that I’m not entirely sure where home is. I live in LA but, like ET again, it feels more like a way-station before I get to where I should really be.

With such thoughts in mind, I landed at Detroit, a city whose landscape suggests not the extra-terrestrial, but the day after they’ve landed. The overwhelming impression is of space, which in itself is not a bad thing, but here there is space where there shouldn’t be, empty lots run into one another forming improbably vast fields between one building and another. With its trashed warehouses and burnt-out homes, its image of irreversible urban blight, it’s no accident that Detroit is the setting for the Robocop films and their familiar toying with proto-fascist solutions. (A new urban warfare videogame was described as “Detroit having elected Joseph Stalin for mayor.”)

And yet, like other human no-go zones, it’s apparently good for wildlife, and I heard one tale of pheasants finding refuge in the city from hunters. Like pheasants in the city, dereliction can be picturesque. An exhibition of paintings by Robert Gniewek at the Lemberg Gallery consisted of photorealist Detroit street scenes that are impeccably painted yet face that familiar problem of aestheticizing poverty and neglect.

There are still grand remnants of Detroit’s heyday, markers of abundant wealth and unfettered ambition that seem somehow quaint in their humanist paternalism— monuments to the human spirit and all that. They might be relics of a bygone era of plenitude, but they remain undeniably powerful as presences.

The Guardian Building downtown, completed in 1929, is a forty-story Monument Valley butte that’s dropped out of the sky, and with its “tangerine” masonry, seems bathed in early morning desert sun. It’s an expressionistic mélange of whatever hit the fan: a whole lot of Aztec, big chunk of Deco, a little Native American, some riffs of jazz, sprinkle of Dutch, a drizzle of Arts and Crafts. I walked into the main lobby… and wanted to laugh. It’s so exuberant in its obsessive detailing, its bursting forms and vivid colors that it borders on the absurd, and yet the effect is of being uplifted by the sheer excess. Not for nothing is it referred to as a cathedral to finance.

Conversely, the 1913 Beaux Arts-style Michigan Central Railroad Station has been abandoned since the ‘70s. When seen at dusk, it loses all detail of its interior decoration and thrusts out of the ground with gothic splendor like a (Ku)brick monolith. With most of its windows smashed, one can see right through, the portals of dark gray sky like phantoms against the hulking black. Protected by chain-link fencing topped with razor wire and surrounded by, again, empty lots and deserted streets, I felt I was a trespasser at a massive tombstone.

It also made me rethink Gniewek’s paintings; after all there is an undeniable sublime pleasure in witnessing destruction. One is awed by its power and extent, and thankful that one can walk away, leaving others to suffer it. It’s the same with looking at the paintings: they have a certain beauty and I’m so glad I don’t have to live there.

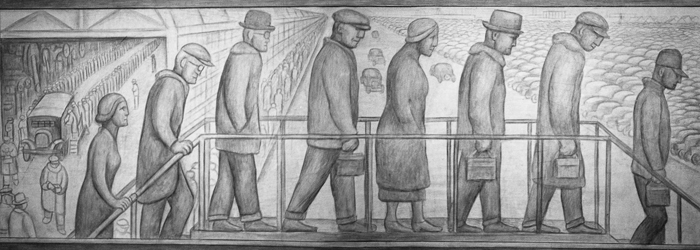

Allan deSouza, Attempt to represent Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Frescoes (1932), 2004

The Detroit Institute of Arts houses The Detroit Industry Frescoes by Diego Rivera (1932). But to get to them one has to pass through the central hall where the permanent collection has been “mixed and matched.” I’ll say. On the left was the large and instantly recognizable Painting, 1951, by Clyfford Still. But why was it hoisted nine feet up the massive wall, and why was there a cabinet display of swords beneath it? Try as I might, I could find no logic for the odd coupling. The collection continued with these peculiar juxtapositions that defied any classification system, but which nevertheless made the works strangely memorable. Maybe other museums should try this; just stick the work anywhere and let the viewer figure it out. It might make for multiple visits just to see what they’re going to do next.

Through this hall of art historical sacrilege, one enters what used to be known as the Garden Court, its four walls bearing the fabled frescoes. Walter Benjamin would have loved this. Aura? The frescoes were practically glowing. You can’t reproduce a fresco since the image doesn’t reside upon the surface but within it. It simply has to be seen on site in its original and only form. Of course, the mythification of Rivera adds to the glow.

For the most part, the frescoes are a celebration of (hu)man and machine—this after all is before WWII and before Stalin’s state machinery. The centerpieces are heaving depictions of the factory floor, intricate mazes of pistons, gears, cogs and conveyors all set in motion by heroic workers. The upper sections provide an agricultural complement, with depictions of bountiful harvests clasped by equally bountiful women. So far this is standard Social Realism, yet it’s a curious and unwitting celebration of capitalism by the singularly communist Rivera. He does, however, add idiosyncratic touches that upset too easy a reading. On the south wall, one machine rises triumphantly, resembling the Mexican Rain God, Tlaloc. Although Rivera still believed in a technological utopia, viewed now through our post-Terminator (and post- Gubernator) lens, this vision of mechanical power can only be sinister.

At the top right on the north wall, a curious scene unfolds. It appears to be a nativity complete with barn animals, but the golden haired, diaper-clad infant is actually being vaccinated by a Joseph-like doctor, while the three Magi are scientists working in a lab. Preceding the furor over the Rockefeller Center murals in New York, this scene in particular stirred the ire of the 1930s version of the Religious Right.

Rivera also includes a fetus, what he called a “germ cell,” as progenitor of human and cultural possibility. Some have seen it as a reference to Frida Kahlo’s miscarriage while she accompanied Rivera in Detroit. Kahlo, apart from this loss, also hated Detroit for its nouveau riche provinciality and liked to stir it up a little; she once asked the notoriously anti-Semitic Henry Ford (Ford Motor Company having funded the frescoes) if he was Jewish. But the image I like to take away with me, and one captured in a photograph, is of the two of them, Rivera and Kahlo, tenderly smooching atop the scaffolding during a break in painting.

Out in the suburbs of Detroit, past the Eight Mile city limit, I visited a show of large-scale drawings at Oakland University. From Susan Goethel Campbell’s ethereal clouds, Tony Hepburn’s sprayed and disc-sanded hospital beds, and Stephen Talasnik’s spiraling architecture to Joseph Stashkevetch’s close-ups of fish, the works all used recognizable imagery though not necessarily for representational ends. At the same time, the process and the qualities of the medium itself were equally important. Michigan artist Larry Cressman pushed farthest the possibilities of the medium. Against the eloquent but not unexpected gestures of the other artists, his work stood out as ugly, finicky, obsessive (though I also worried about Stashkevetch’s unnatural concern with fish), and it looked like the walls had been shredded prior to demolition. But perhaps because of having just seen the Riveras, I was attracted by Cressman’s particular disdain for the neatly contained drawing, turning it instead into site-specific installation. The fact that his works were individually cut lines of graphited paper that were pinned, glued, wired and sewn to the wall in controlled explosions recalled the methods of fresco painting, of indelibly mixing the adherent into the adhered.

At nearby Cranbrook Museum of Art and Cranbrook Academy, where I was invited to give a lecture, the first impression is of an English country estate with cultivated woods and rolling fields. Until, that is, the museum comes into view. With its brusque formality, slab-like walls, hard-edged pillars, and flanked on one side by bronze figures cavorting around a fountain, and on the other by a bronze of Europa playing with her bull, it has all the delicacy of an Albert Speer building. Inside however, it’s another matter. The walls are edged top and bottom with extruding wood skirts that must make hanging any artwork a challenge since one’s eyes are constantly drawn up or downwards, yet they lend a reassuring warmth and weight to the walls. In contrast, I’ve heard that at the new MoMA in New York the walls appear to float.

There’s mix and match at play here, too, in the exhibition of the permanent collection, but here it’s done with a finely tuned eye. A Charles and Ray Eames wooden screen (Folding Screen-Wood, 1946) ripples behind a cute Eero Saarinen-designed droplet of a chair (Tulip Side Chair, designed 1955-57, made 1977). Both seem to flow off an adjacent Bridget Riley (Shih-Li, 1975), which is already set in undulating motion by the stillness of a nearby Agnes Martin (Untitled, 1974). Facing the Riley is the equally energetically surfaced Bull’s Roar (1986) by Anne Wilson, a synthetic recreation of the ragged and flayed hide of said bull. Next to that, in a witty and poignant pairing, is a John Coplans self portrait (Back and Hands, 1984), a towering expanse of hairy and age-marked back, topped by gnarled and also-hairy knuckles.

While there’s an emphasis on Detroit and Cranbrook-affiliated artists (the afore-mentioned Wilson, for example), there are a lot of iconic works here. There’s a thrill of anticipation in seeing something like the Rivera murals, but I prefer this experience of walking into an unknown space and unexpectedly seeing works that I’ve admired over the years but only in reproduction. I like that surprise that stays with you for days, like when I dutifully visited the local museum of a town in Portugal’s Algarve, only to encounter Duchamp’s Bottlerack!

Allan deSouza, Art Outpost: The Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit, a community nonprofit, not to be confused with the Detroit Institute of Arts, 2004

The academy, literally next door, has an unusual system of a single faculty person per department that reflects its origins in a pedagogical system based on apprenticeship. Without formal classes, emphasis is placed on self-motivated studio practice. It seems to work. I walked around at ten on a Sunday morning and the studios were already bustling. Students show their work regularly and that weekend there had been an exhibit referring to recycling and human relationships to nature that included hay bales, mulled wine, and a couple of live calves tethered to a salt lick (a bucolic counterpoint to the previously encountered raging bulls).

Jane Lackey, the head of Fiber Arts, was busy in her studio. Her work has the precision of someone who has actually been trained in a discipline, and the scope of someone who isn’t restricted by it. There’s one work on the wall, SNPS/slips (2002), but it’s not immediately apparent what I’m looking at. Gradually it dawns that what looks like skin or parchment are actually Damien Hirst-like slices through the thickness of dictionaries, and the tiny mottling on the surface are cuts through the ink-thin printed letters.

Lackey incorporates slips of the tongue and spoonerisms; embarrassingly, the example I remember most—though it’s hardly typical—is “pun fart.” If Freudian slips reveal something about the speaker, what do they reveal from what one remembers? Lackey’s work also recalls the LA poet Harryette Mullen’s sizzling plays on words, and her one book in particular, Sleeping With the Dictionary. What fun if the two of them were ever to collaborate.

It’s been a whirlwind trip. At a Dull(es) layover, I’m walking past the “America!” store and feel compelled to stop in, feeling that it would be un-American to not do so. Forget the usual paraphernalia of patriotic pride, the White House key rings and First Lady t-shirts, FBI mugs and Secret Service baseball caps. I recommend the paper doll cutout book, with Bushy and Bushier in their underwear (though the twins-fortunately or not, depending on one’s tastes—remain decently clothed). The Great Unclothed (naked Emperors anyone?) come with a selection of costumes, from back-on-theranch to full formal wear. Hours of fun for Reps and Dems alike and, I think, a genuine tool for healing this divided nation.

On the final leg to LA, the on-board movie was Collateral, with Tom Cruise as a stereotypically pathological hired-killer, finally outwitted and outgunned by a regular-Joe cab driver. A by-the-numbers Hollywood fantasy of the gritty but ultimately heart-warming underbelly of LA life, it offers one moment of genuine interest for art insiders. One of Cruise’s targets—who gets bloodily dispatched amongst the carnage of collateral bodies (hence the title) in a crowded Koreatown nightclub—is the real-life Inmo, the owner of the now-defunct Chinatown gallery bearing his name. Welcome home, or welcome back to the way-station, I thought, and flashed back a couple of months to when I’d last seen Inmo, a kind of taller, bulkier Sammo Hung, doing an unlikely yet impressive karaoke rendition of Steven Tyler “walking this way.”

One of many failures with Hollywood is that, no matter how hard it tries, it can never quite capture the true unreality—the homegrown alien-ness—of life on its own doorstep.

As always with this column, I am grateful to a number of insightful and generous individuals for sharing and putting up with this tourist. Thank you all.

Allan deSouza is an LA-unbased artist and writer.