Roland Barthes understood that photography’s seeming promise to give form to loss is also a great cruelty. Photographs only flirt with restoration; they cannot stop time or return the beloved.1 The past, in photographs, remains otherworldly in its incompleteness. What follows is an examination of the work of two contemporary art photographers—An-My Lê and Sally Mann—who address two past American conflicts, the Vietnam War and the American Civil War, respectively. In doing so, they point to the complicated construction of historical narrative, highlighting what is knowable and unknowable about the past. Lê and Mann’s pictures make apparent that histories, particularly traumatic histories such as war and expansionist ideologies, are not clean, clear, or simply understood through retelling. Rather, their work acknowledges that these histories have aesthetic dimensions; their pictures provide a powerful visual experience that derives some of its power from its visual references to the photographs of past American wars.

Sally Mann is a Virginia-based artist best known for her 1992 book, Immediate Family, an idyllic, wild, and at times violent series of photographs of her three children. Mann’s work is grounded in the Southern Gothic, a genre that focuses on the more macabre elements of Southern culture. Her work visually hints that the dead might not be fully at rest, and the living not untouched by decay. “The repertoire of the Southern artist,” she writes, “has long included place, the past, family, death, and a dosage of romance that would be fatal to most contemporary artists.”2

In the 1990s Mann transitioned from photographing her children to the landscape around them.3 The landscape photographs are often aggregated with other images that highlight her preoccupations. Mann’s 2003 book, What Remains, is divided into thematic groupings within a larger conversation about death and mortality. One grouping shows the decomposition of Mann’s dead greyhound, Eva. Another, which is identified as being taken at a “forensic study facility,” shows bodies that have been left out to decay for research purposes; these images have a broad tonal range, with evocative detail in the shadows that only comes into focus on close examination. Published in 2005 as a collection titled Deep South, Mann’s landscape series begins with her family’s land in Lexington, Virginia, before moving further south to Georgia, and then to “the deep south” of the title, Louisiana and Mississippi. The final section, “Last Measure,” contains images of Civil War battlefields. These pictures are named for the places that have become synonymous with the violence carried out there: Antietam, Manassas, Wilderness, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville. Mann’s titles direct the viewer to the pictures’ historical significance, but the viewer—given little other information, visual or written—is asked to fill in Mann’s landscapes with the past. Personal reflection becomes crucial to the pictures’ meaning.

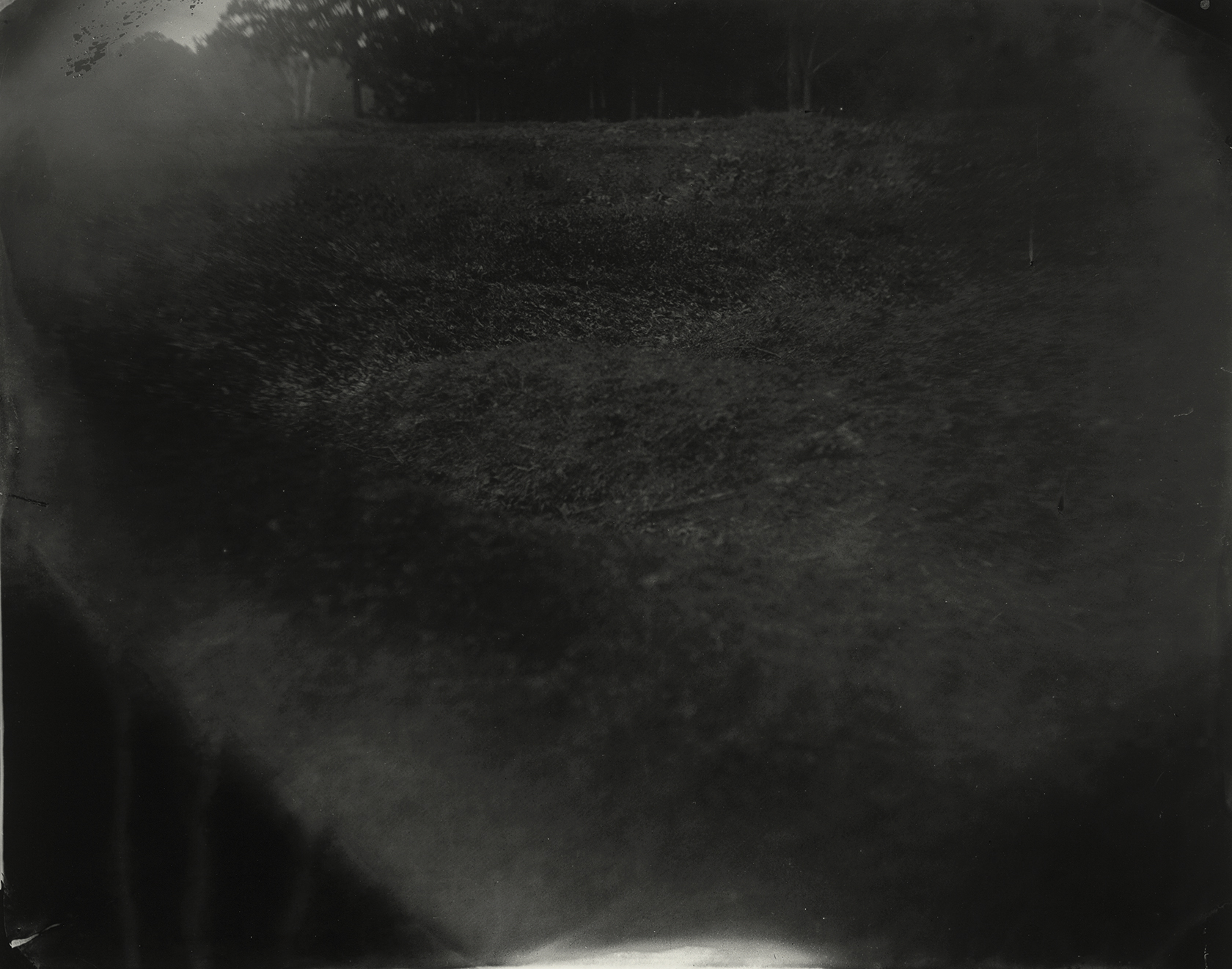

Sally Mann, Untitled (Antietam #11), 2001. Gelatin silver enlargement print, printed by the photographer from the original wet-plate collodion negative; dry-mounted, and finished with custom mixed Soluvar varnish; 40 × 50 inches. © Sally Mann. Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

The Antietam pictures, taken only a few hours from Mann’s Shenandoah Valley farm, depict fields where over 23,000 Americans were killed or wounded. When measured in American lives lost in war, Antietam is the bloodiest day in American history.4 Mann quotes Shelby Foote’s novel Shiloh (1952) in a text that accompanied her first showing of the battlefield pictures, in a 1997 show called Motherland: “We were in love with the past …in love with death.”5 The text places the experiential emphasis on the viewer rather than the historical actors. The pictures, the captions suggest, are a meditation on history and mortality. They do not provide an understanding of the lives and deaths of those on the battlefields of Antietam and Manassas. Rather, it is Mann’s and the viewer’s fascination with both the past and the certainty of death that makes the pictures compelling. Mann’s Civil War battlefield pictures explore trauma and the complications of narrating it.

For the last two decades, scholars have used a psychoanalytical framework as a mode of investigating histories of trauma.6 These scholars, predominately historian Dominick La Capra and literary theorist Cathy Caruth, have argued that traumatic histories of extreme violence create further difficulties for those interested in more traditional, non-visual forms of telling, because trauma—both at an individual and societal level—is by definition an experience that will not integrate into narrative.7 Academics have more recently become interested in ways of telling that take into account how violence lingers. Literary theorist Marianne Hirsch shows that trauma is not only the domain of firsthand experience.8 She uses the term “post-memory,” to characterize “the experience of those who grow up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth.”9 Additionally, Ulrich Baer, a professor of German and Comparative Literature at New York University, has demonstrated the usefulness of photographs as a framework for understanding trauma. In his 2002 book Spectral Evidence, Baer brings together Sigmund Freud’s understanding of trauma as a “reality imprint” and the highly theorized idea of the photograph as an “illusion of reality,” arguing that the photograph mimics the visual nature of traumatic memory.

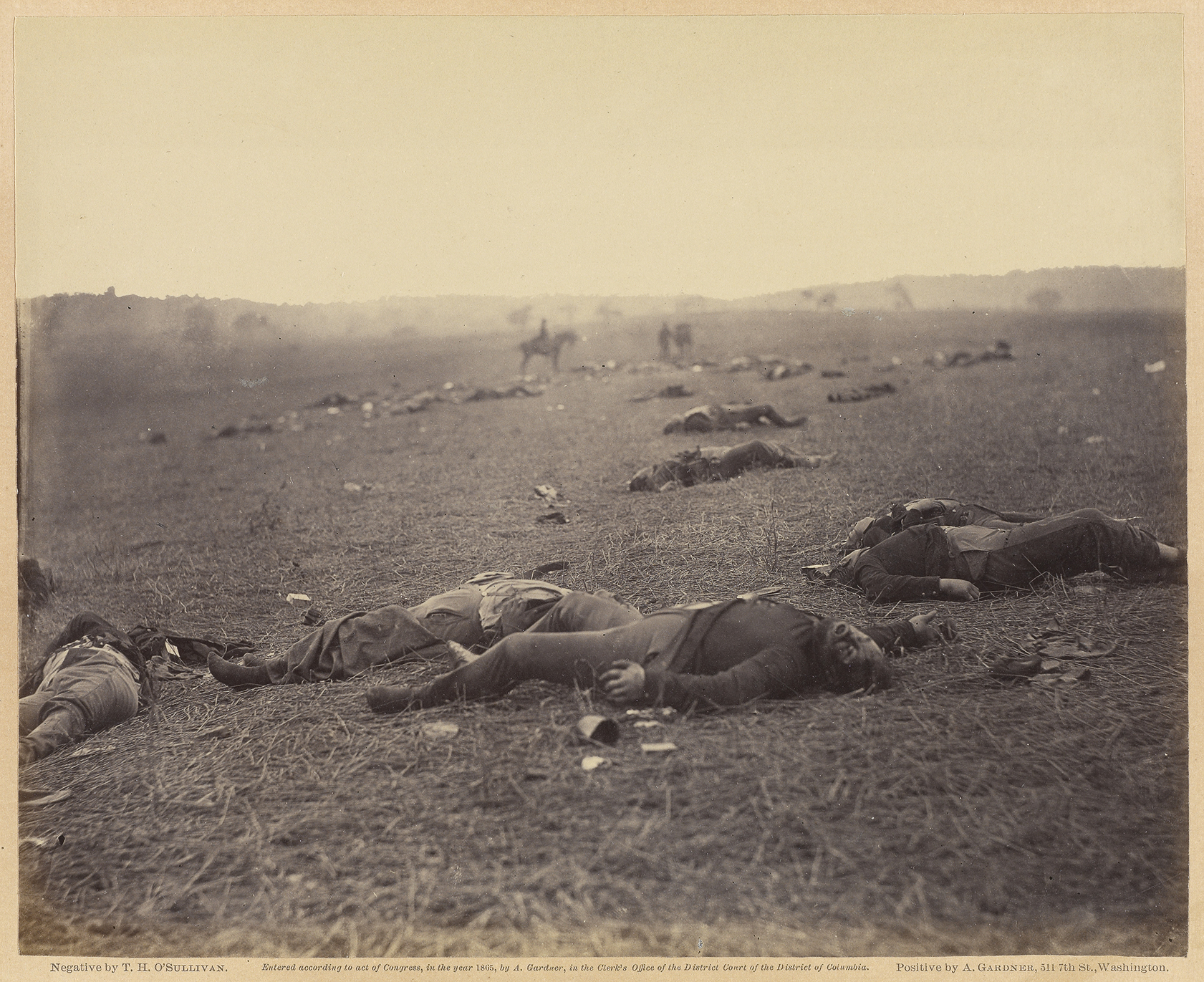

Timothy H. O’sullivan, A Harvest of Death, negative: July 4, 1863, print: 1866. Albumen silver print, 7 × 8 inches. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Mann’s photographs contain many of the same landscapes that appeared in the work of the great Civil War photographers, including Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan. Historian Charles Royster argues that Gardner and O’Sullivan’s photographs served for contemporary viewers as “partly a flight into unreason: into visions of purgation and redemption, into anticipation and intuition and spiritual apotheosis, into bloodshed that was not only a pursuit of interests of state but also sacramental, erotic, mystical, and strangely gratifying.”10 Mann’s pictures, like those that Royster describes, are landscapes—sweeping views in which land and sky merge at a distant vanishing point. O’Sullivan’s photos show bodies spread out across battlefields in poses that feel strangely precise, almost poetic. (It’s been established that the Civil War photographers contrived some of these poses, moving dead bodies.) Mann’s pictures, on the other hand, are a kind of counterpoint to O’Sullivan’s; while his are documents of violence, her pictures conjure an absence, into which the viewer is left to read meaning. In Mann’s pictures, the war dead of Gardener’s and O’Sullivan’s photographs have been replaced by empty space—suggesting, as Mann has put it, “the land’s ability to move beyond, to recover, from mass bloodshed.”11

Sally Mann, Untitled (Chancellorsville #9), 2001. Gelatin silver enlargement print, printed by the photographer from the original wet-plate collodion negative; dry-mounted and finished with custom mixed Soluvar varnish; 40 × 50 inches. © Sally Mann. Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

Like the Civil-War-era photographers, Mann uses a large bellows camera, nineteenth-century brass-rimmed lenses, and glass collodion plates. The collodion process, one of the most difficult photographic practices to master, requires coating the glass plate in the field and keeping it damp while the image develops.12 Mann notes that collodion, a highly flammable, syrupy chemical compound, was used to dress wounds during the Civil War, further connecting the photographic process and historical attempts to heal violence done to the body.13 In Mann’s pictures, trees can be clearly seen, as can the delineation of sky and land. The pictures are heavily contrasted, with large areas of rich black earth in the foreground from which no detail can be made out. Bright light clustered in the corner of certain frames, such as Untitled (Chancellorsville #9) (2001), seems to promise a spiritual transfiguration that never comes. The picture’s ghostly absence implies something significant but inaccessible to the viewer. Offering no narrative resolution, Mann’s pictures are neither consoling, commemorative, nor redemptive.

Baer argues that the tradition of landscape, dating back roughly two hundred years to the Romantics, encourages the viewer to engage in a kind of circular reflection.14 The violent, hazy seas of J. M. W. Turner’s Slave Ship (The Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) (1840) and Caspar David Friedrich’s Wonderer above a Sea of Fog (circa 1818) exemplify a tradition in which the landscape serves as a metaphor for internal states. The sites are depicted to point the viewer back to her position in relation to the land.15 In the case of Mann’s photographs, the viewer is asked to reconsider her own experiences in relation to the historical violence that haunts the otherwise empty landscapes.

An-My Lê’s family relocated from Vietnam to the United States in 1975, the year North Vietnamese nationalist forces wrested Saigon from United States control. From a United States point of view, this was an unprecedentedly photographed war, and the first reproduced in the media in color. In the 1990s, Lê began photographing American Vietnam war re-enactors in rural Virginia and North Carolina with a 5 x 7 view camera.16 She spent four summers both documenting and participating in restaged battles.17 The resulting black-and-white portraits and landscapes were published in 2005 in a book titled Small Wars.

Larry Burrows, Ammunition Airlift, Operation Pegasus, Khe Sanh, 1968. Dye-transfer print (printed later), 20 x 30 inches. Larry Burrows/LIFE. © Time Inc.

Lê is a technical and skilled image maker. Her photographs have the same eerie, cinematic quality apparent in the pictures of Larry Burrows, who made his reputation photographing the Vietnam War for Life magazine. Burrows, a photographer in the “habit of edging right up to death,” showed the devastating beauty of the air war and the efficiency of American soldiers in strikingly composed and vividly colored images.18 He also complicated the genre of war photography, as it had developed in Life and elsewhere. Unlike Robert Capa, W. Eugene Smith, and other masters of the genre, Burrows’s photographs seem less like self-contained sublimations of events and conflicts and more like stills from a war movie that doesn’t exist. The resulting sense of confusion and disorientation is a quality that many of Lê’s re-enactor photographs share.

Lê’s pictures are self-consciously ambiguous—inviting the viewer to fill in the gaps in meaning that occur when real wars are merged with false locations and bloodless spectacle—in a way that war re-enacting rarely is. Rather, her subject is notable for its participants’ obsessive attention to detail—what journalist Tony Horwitz describes as a “hardcore” engagement with facts.19 Re-enactors live, train, and restage as close to documented history as possible. The re-enactor community takes authenticity to an extreme. Often even food and language are limited to that of the period being restaged.20

An-My Lê, Small Wars: Explosion, 1999–2002. Gelatin silver print, 26 × 37 1⁄2 inches. Courtesy Murray Guy Gallery, New York.

An-My Lê, Small Wars: Rescue, 1999–2002. Gelatin silver print, 26 × 37 1⁄2 inches. Courtesy Murray Guy Gallery, New York.

War re-enacting attempts to turn the re-staging of history into a kind of epistemology. As Will Dunaway, a collodion photographer and Civil War re-enactor, explains, the goal is to get to what the re-enactor community calls “shining times,” moments when the history is staged so well, so accurately, that the re-enactor feels herself transcending history and slipping into the experience of the historical figure she seeks to emulate.21 These are, of course, imagined connections, and often ones with dangerous political connotations. Civil War re-enacting, in particular, often makes a fetish out of the racial hierarchies of the past. The re-enactor’s relationship with the past is an eroticized one that offers the gratification of playing out fantasies of someone else’s power, killing, or death. They are physically “safe” wars that allow participants, Lê included, to delve into fantasies of military aesthetics—uniforms and other pageantry—while remaining unharmed by the wounding and killing that defines the reality of war. In Lê’s pictures, the violence is staged; the (viewer’s, re-enactor’s, and photographer’s) fascination with a violent past is not.

Lê and Mann aren’t interested in bridging the experiential gap between the viewer and the historical subject or providing the viewer with any concrete knowledge. Rather, their works call attention to the viewer’s distance from the past—while also highlighting the ways that viewer, photographer, and historical subject all occupy different positions in relation to historical events. In Lê’s and Mann’s photographs, the viewer is twice removed from the experience of the historical subjects. The first line of separation is the distance between those who have experienced trauma and those who have not.22 The second is that of time’s passing.

The re-enactors in Lê’s pictures are too young to be Vietnam veterans and, as a result, their memories of Vietnam come from not the war itself but rather its representation in broader American culture, including photographs, television, movies, and books. The same is true of many viewers of Lê’s photographs. Lê’s memories, which come from the actual war she lived through and the American culture she grew up in, are more complicated. As Lê put it in a recent interview, “The re-enactors and I have each created a Vietnam of the mind and it is these two Vietnams which have collided in the resulting photographs.”23 The histories of Lê, the re-enactors, and the viewers overlap, merge, and conflict, offering a past that lingers in the images with no power to transcend. Among other responses, the photographs can offer viewers a meditation on the limits of empathetic identification and the complication of collective memory in relation to an extremely divisive war.

Drawing on the language and history of documentary photography, Lê’s work is both document and fine art. But unlike photographs that are entirely staged for the camera, in Lê’s pictures the question of authenticity shifts from “pretend war” to “real re-enactment.” In another series, 29 Palms, Lê shows a marine training facility in Fort Irwin, California, that has been transformed by the U.S. military into a generic Middle Eastern town that is used for war games.24 In these pictures, the (real) soldiers train for wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. By not conforming to the viewers’ expectations of what a war photograph should be, both of these series by Lê leave room for the viewer to consider questions outside the expectations of the genre, such as how we draw lines between categories like “war” and “not war,” “training” and “re-enactment.” This confusion is not unique to Lê’s work. For example, O’Sullivan’s moving of bodies during the Civil War to create the picture he wanted was a kind of re-enactment. His pictures were the aftermath of a real battle, but he chose to alter them to fit the viewers’ and his own expectations of what a battle scene should look like, based on historic paintings and other sources. Lê’s pictures, however, bring the slippage between real and imagined to the viewer’s attention more insistently.

In Lê’s and Mann’s work, the pull of the past meets the fantasy of transcending it, a fantasy that their photographs consistently frustrate. In their pictures, the past is indeed a foreign country, available through reference grounded in photography’s history but ultimately inaccessible. Their photographs place the viewer in a relationship to history but also deny her access to the past, demonstrating that the only relationship possible with the past is a mediated one. Even so, photography can offer something that is perhaps more compelling than knowledge. It illuminates our own ghosts.

Elaine McLemore teaches Art History at Azusa Pacific University. Her work explores twentieth-century American photography and politics.