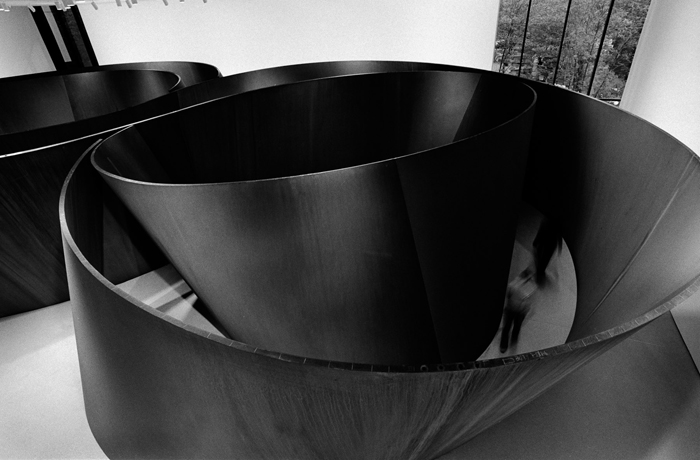

Richard Serra, Sequence, 2006. Weatherproof steel. Overall: 12’9” x 40’ 8 3/8”x 65’ 2 3/16”. Collection the artist. © 2007 Richard Serra/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Lorenz Kienzle

Richard Serra, Sequence, 2006. Weatherproof steel. Overall: 12’9” x 40’ 8 3/8”x 65’ 2 3/16”. Collection the artist. © 2007 Richard Serra/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Lorenz Kienzle

Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years, the Museum of Modern Art’s selective survey of the artist’s estimable career was presented in three discrete sections. Most of the early work (1966-1986) was installed on the sixth floor of the museum; two sculptures from the 1990s occupied the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden, while the monstrous second floor galleries were devoted to three pieces, all executed in 2006. Though the exhibition was supposed to run through September 24th, in fact, the sixth floor of the show closed to the public almost two weeks before that date, and the outdoor portion on the 22nd. Resultantly, this reviewer saw only the second floor presentation and the outdoor installation—in other words, a truncated late career survey spanning the years 1992 to 2006—a profound disappointment which proved unexpectedly revealing and generative, specifically when thinking about Serra’s latest body of work.

An implied affinity with manual labor and industrial manufacture has since the late 1960s been the lynchpin of Richard Serra’s considerable international reputation, and central to the muscular autographic style he has cultivated on a ballooning scale and with increasing ambition over the last forty years. One thinks immediately of the now-iconic image of a young, robust Serra, arms aloft, frozen in the act of flinging molten lead against a wall, dressed in protective garb, as if for the apocalypse. Like Hans Namuth’s filmic account of Jackson Pollock prowling around his floor-bound canvases, in thrall to an untamed impulse, this image dramatizes Serra’s self-styled identity as worker/artist. This tenuous conflation of labor and the act of artistic creation has been foregrounded consistently in the voluminous literature that surrounds the artist’s work, and, perhaps more persuasively, in the images that document (and fetishize) their creation. One need not look far for a potent example.

The cover of the exhibition catalogue published to accompany this show features a sweeping black and white image of Sequence, 2006, a sublime, labyrinthine work temporarily installed at Pickhan Umformtechnik GmbH in Siegen, Germany, where the work was fabricated. Like almost every widely circulated image of a Serra sculpture—and indeed every image in MoMA’s catalogue—the photograph is black and white, uncannily sharp, and moodily atmospheric. Two unidentified men stand in the center of one sweeping steel spiral, dwarfed by the immensity of their environment. Taken in a working factory, this photograph emphasizes a few key documentary details designed to inflect the way Sequence is understood. First, and most obviously, the sculpture’s character is closely aligned with the circumstances in which it was manufactured—a German foundry—and, more obliquely, with those factory workers instrumental in its fabrication. The utilitarian geometry of industrial tools and machinery provides an authentic background for the undulating steel form, while the rough concrete floor echoes the unvarnished appearance of contemporary exhibition spaces such as Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. Process, materiality, and product are thus conflated in this photograph to produce a compound impression of the sculpture’s rough, industrial character.

This short account of Sequence aligns seamlessly with Serra’s self-image historically, and with the art world’s received understanding of his work, dating back to early floor-bound sculptural efforts such as To Lift (1967), Doors (1966-67), and Scatter Piece (1967). In each of these works, regardless of material, Serra’s process is palpable, intelligible, and seems to have occurred on a human scale. To Lift, for example, feels visceral and intimate. One can imagine Serra, aided and abetted, perhaps, by an informal band of helpers, manipulating the vulcanized rubber into a form that literally embodies the infinitive verb that is the object’s title. The sculpture successfully collapses index, process, material and form into one seamless, gestalt gesture. On the basis of the aforementioned photograph, it might seem natural to conclude that Sequence represents the artist’s grand summation of these concerns—a monumental work, executed on a colossal scale that draws on processes of industrial fabrication to produce a sublime phenomenological experience, a figment of the mind rendered in steel.

Richard Serra, To Lift, 1967. Vulcanized rubber. 36” x 6’ 8”. Collection of the artist. © 2007 Richard Serra. Photo: Peter Moore.

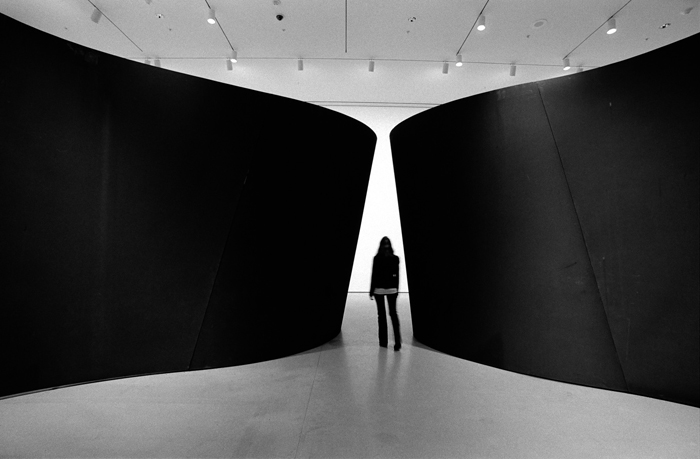

Richard Serra, Torqued Torus Inversion, 2006. Weatherproof steel. Two torqued toruses, Each overall: 12’ 9” x 36’ 1” x 58’ 9”; Plate: 2” thick. Collection the artist. © 2007 Richard Serra/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Lorenz Kienzle.

However, one’s physical encounter with Sequence, and indeed with each of the three works made in 2006 included in the show, demands a revised understanding of Serra’s late practice, for in their unabashed grandeur and elegance, warm, painterly surfaces, and soft, graceful curves, these sculptures hue closely to their fundamental ontology as precious works of art, and depart considerably from the raw, industrial aesthetic that has typified Serra’s work. It is far more difficult to imagine Serra’s hand at work in these sculptures, and at least two of these pieces—Band and Sequence—are so monstrous that their forms bleed into unintelligibility. The combination of aloof grace and staggering scale is, frankly, alienating.

None of this is to suggest, however, that the phenomenological punch of Serra’s work has become dilute over time; far from it. In fact, these massive objects may be more coercive and manipulative than any other works in Serra’s vast oeuvre. This effect issues in part from the fact that each sculpture is so large and structurally complex, and fills the enormous gallery spaces at MoMA so thoroughly, that is difficult to develop a comprehensive schematic understanding of any one piece before or during the physical experience of the object. Band (2006), for example, is an exhilarating exercise in staged sublimity. Comparable to watching enormous breakers forming, crashing into nothingness, and then reforming minutes later, one is made viscerally aware of one’s powerlessness in the face of this work. As the viewer proceed blindly through expansive open spaces and narrow passageways, impenetrable walls of steel soar and undulate, monopolizing one’s entire field of vision. Walking from one end of Band or Sequence to the other does not produce a comprehensive impression of the sprawling form, but instead offers a phenomenological experience that engulfs and confuses the senses, limiting visual intelligibility particularly. The sublimity of the experience, therefore, derives in large part from the sensation of implied threat counterbalanced by a forced faith in sound engineering.

Though the overall form of Band evades the eye, the surface of the weathered steel provides an unexpectedly delicate visual feast, another facet of the work which, along with the sheer, daunting presence of the sculpture, is obscured by the elegant black and white photographs that so often represent Serra’s work. The same applies to the third and final work from 2006 installed on the second floor, Torqued Torus Inversion. As seen in the black and white catalogue photograph, the two sculptures that comprise this work have a stark, graphic presence that is almost brutal in its simplicity and emphasis on contour. The impression provided by this image, however, belies completely the experience of the object itself. Radiant and voluptuous, the sculptures omit a warm glow as the viewer enters into the simple womb-like interior space created by each form. Once inside, the surfaces of the weathered steel are varied and captivating. Random streaks and passages of oxidization intermingle with glowing fields of deep orange and brown to produce an rich visual field at least as compelling as a Gerhard Richter abstraction. If the dimensions and contours of these sculptures are the result of meticulous planning and engineering, then the beauty of the surface results from precisely the opposite process—happy accidents of material and industrial facture. The visual experience of this work, therefore, demands a mode of lyrical description completely incommensurate with the scale, weight and rhetoric of the torqued steel mass. If the grammar of an object should determine the tone and structure of the writing about it, then the photographs of Serra’s latest work and the physical experience of those same objects in space demand two entirely different accounts.

Delicacy of surface aside, there is no escaping the fierce physical character of this work. This is nothing new for Serra. Latent (and not-so-latent) threat has been central to his repertoire for years. In Delineator (1974-1975), for example, he installed one hot-rolled steel plate on the ceiling and another on the floor below, forging an unsettling but thrilling phenomenological condition. The stakes of this piece are clear and immediately evident to the viewer: in order to experience the brute force rush of the sculpture, viewers must stand in between the two steel sheets, turning their trust over to the artist and to the team of engineers that installed the object. Delineator performs and thematizes danger perfectly, offering a brutally simple experience, which viewers can either accept or reject. Band and Sequence operate differently, disempowering the viewer as effectively as Delineator demands personal agency. The surfaces are soft and seductive, full of passages of elegant oxidization that charm the eye. One is lured deep into the twists and turns of the object, and provided with an acutely disconcerting, maddeningly coercive funhouse experience, minus the essential choice that precedes the experience of works like Delineator.

Richard Serra, Band, 2006. Weatherproof steel. overall: 12’ 9” x 36’ 5” x 71’ 9 1/2”; Plate: 2” thick. Los Angeles County Museum Of Art. Gift of Eli and Edythe Broad. © 2007 Richard Serra/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Lorenz Kienzle.

Richard Serra, Band, 2006. Weatherproof steel. overall: 12’ 9” x 36’ 5” x 71’ 9 1/2”; Plate: 2” thick. Los Angeles County Museum Of Art. Gift of Eli and Edythe Broad. © 2007 Richard Serra/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Lorenz Kienzle.

Admittedly, Serra’s latest sculptures are saddled with the considerable burden of following a singularly powerful, autographic body of work, that—arguably—stands alone in the pantheon of twentieth century sculpture. Distinguished by his interest in utilizing and thematizing industry and labor in his formal exploration of weight, mass, volume, line and contour, Serra has produced some epic phenomenological situations. In certain instances, most notably Tilted Arc (1981), he even managed to use his obdurately formal work to provoke discussions about how we as a culture occupy and share space. Band, Sequence, and Torqued Torus Inversion, however, do not complicate or elaborate upon the conceptual concerns of his early work, but rather enumerate the same phenomenological issues on a more ostentatious, institutional scale. Serra’s late-career concerns, therefore, seem to lie more with size and technical complexity than with critical substance. So, while these colossal, almost architectural works are inevitably awe-inspiring, they are also strangely tame and familiar.

The architectural scale of these sculptures may itself be revealing, for it is difficult to think about Band or Sequence without reflecting on Terry Smith’s understanding of the economic function of spectacular destination architecture within what he calls “the iconomy”—a system of value wherein the success of an image is measured according to its marketability and reproducibility, its ability to mark a place as a destination, and lastly, its capacity to activate desire and consumption in the viewer.1 Within such a system, what, then, is the social function of a work like Band? What kind of currency does it hold? Who is equipped to purchase and care for a work on the scale of Sequence? Where will it be installed and what type of experience might it generate? Will it disrupt and agitate urban social practices, as did Titled Arc? Will it provoke discussions about the meaning of labor and art in a working class town, as did Terminal (1977)? Or do Richard Serra’s grand, late works operate in an entirely different economy now?

Christopher Bedford is an art historian, critic, and curator based on Los Angeles.