Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, c. 1819. Oil on canvas; unframed: 13 x 17 1/2 inches. Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

JN: We’re nearly finished, but I have to ask–is there a “German spirit” in painting?

GR: I believe so, yes. But I’d rather not know the details.1

The exhibition From Caspar David Friedrich to Gerhard Richter: German Paintings from Dresden at the J. Paul Getty Museum (October 5, 2006-April 29, 2007) is the apotheosis of the art historical slide lecture begun by Heinrich Woelfflin in 1930s Berlin. This is not a good thing. The exhibition constructs what the curators (from both the Getty and the Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden) claim is a “juxtaposition.” This attempt at curatorial verve suffers not only from undeveloped ideas, but from a politically naive presentation of landscape painting in European art.

The exhibition is comprised of three adjacent rooms in the West Pavilion and a series of artwork-to-artwork comparisons spread throughout the painting galleries at the Getty Center. In the first room, a sort of anteroom to the Friedrich-Richter juxtaposition, there are paintings from the Galerie Neue Meister and the Getty by three northern European painters. This room is supposedly organized around the concept of the sublime. (Each of the comparisons found throughout the galleries has a theme, such as “Painting Outdoors,” “Emotional Landscapes,” or “The Female Body about 1900” and includes works by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edouard Manet, and others.) Despite this thematic structure, the first room, perhaps unintentionally, functions as a prelude to the Friedrich-Richter rooms in that it reads as a very brief and unremarkable overview of the subject matter and stylistic penchants of Romantic landscape painting. One cannot help but begin to question the conceptual layout and thoroughness of the exhibition as a whole. Why allow this room of three paintings to be potentially (mis)read as an anecdote about the entirety of nineteenth-century German landscape painting? A room given to Richter’s series of twelve paintings entitled Wald (completed in 2005) and one hanging Friedrich works owned by the Galerie Neue Meister follow.

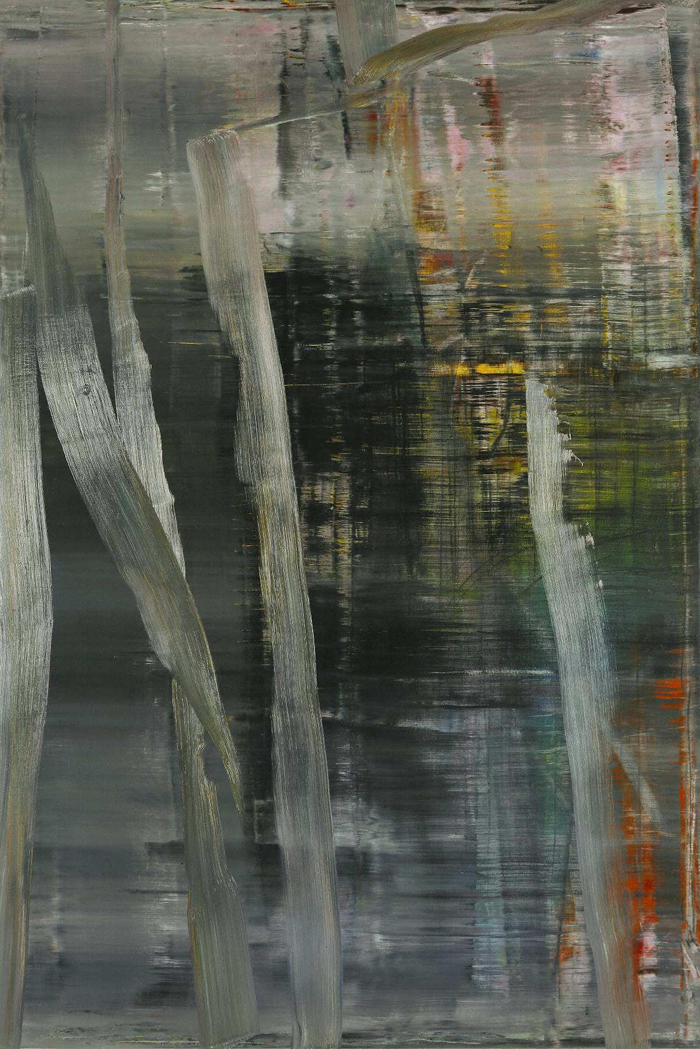

The Richter series of abstract paintings (each oil on canvas is 77 1/2 x 52 inches) is quite impressive. The application of paint on each work is thick and deliberate, but it is tempered by Richter’s practice of using a squeegee to flatten and trawl the surface of the canvas, thereby revealing an immanence of colors, shapes, suggestions of figuration, and a play of light. Each painting presents a generally polychromatic and multivalent surface. Despite resembling several paintings Richter completed in the early-nineties, this series takes on an added dimension via the title Wald, connoting the “forest” or “woodlands.” This title provides a point of reference for the abstract works by connecting them to the history of European landscape painting. When viewing these works, one is confronted with a bloc of sensations that skillfully alludes to this referent. For instance, every one of the twelve paintings has clearly discernible broad, vertical brushstrokes, which both intimates the experience of looking through a forest and suggests concepts prevalent in the history of European landscape painting such as the sublime, solitude, and human insignificance before nature.

Friedrich is represented by eight paintings in an adjoining room. Among those on display, two take prehistoric tombs as their ostensible subject matter. The inclusion of these paintings immediately foregrounds the overt political motivation of Friedrich’s landscapes: the allegorical assertion of a pagan “German” past meant as an expression of nationalist resolve in the face of Napoleon’s 1806 invasion of central Europe. The dialectic of permanence and transience that marks Friedrich’s landscapes must be addressed to this complex historical and cultural context wherein war, invasion, and national identity are determining factors. Without these factors, a painting such as Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar), the centerpiece of the Friedrich room painted in 1807-08, is reducible to religious kitsch. With these factors–which should have been introduced and framed by the exhibition–a work like this would provide an opportunity for a discussion not only of Romanticism (e.g., the elevation of landscape painting to a status previously held by history painting), but politics as well, that is, how the landscape as iconography is implicated in the construction of national identity. Moreover, Friedrich’s presentation of the landscape as an undeniably religious (Protestant) space demands more than a passing reference to Napoleonic Europe in particular and the role played by religion in the construction of German national identity in general.

Caspar David Friedrich, Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar), 1807-08. Oil on canvas; unframed (without glass, frame and pedestal): 45 1/4 x 43 1/3 inches. Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

The presumed “affinity” between Friedrich and Richter, whose own artistic practice develops in the aftermath of World War II amid similar pressing questions of national and religious identity, is never fully developed in regard to either artist’s historical context. Without a rigorous presentation of their respective cultural and historical contexts, that is, how Friedrich’s landscapes are a stage for the Hegelian teleology of Protestant German “spirit” and thus how Richter’s Wald cites and perhaps reinscribes that cultural assertion, this exhibition meanders unnervingly close to mere formalism.2 These issues are not meant to be groundbreaking insights on my part; the problems of comparing and contrasting formal and iconographic affinities without recourse to larger social, political, or even theoretical discourse is certainly a vestige of nineteenth-century art historical disciplinarity.3 In other words, it is the last thing one would like to see in a contemporary exhibition re-presenting the overdetermined concept of the landscape in Western art. What is remarkable is how the exhibition resists its responsibility to address this disciplinary and cultural past.

With that said, it is only fair to acknowledge that the motivating factor for this exhibition is less the art historical juxtaposition of Friedrich and Richter than a collaborative venture by the Getty and the Galerie Neue Meister in Dresden. This collaboration is a reassertion of the artistic and historical importance of the German institution. (The catalogue essays explain the history of the Art Academy in Dresden, its importance for the modernist group Die Bruecke, and how the city’s liberal reputation and association with Modern Art spurred Hitler’s infamous Entartete Kunst exhibition.) Both Friedrich and Richter had strong ties to the Art Academy in Dresden. Friedrich worked and taught in Dresden. In 1816, he was selected to the Dresden Academy, but was ultimately denied a full professorship there. For his part, Richter trained at the academy in post-war East Germany. In 2002, he made a symbolic return to Dresden by setting up his archive at Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, one museum of which is the Galerie Neue Meister. It is within and against this cultural and historical backdrop that Richter conducts his earliest negotiations between the proscriptions of Socialist Realism and his desire to engage a tradition of critical Modernism.

Despite being separated by more than two centuries, the shared importance of Dresden for these two artists is intriguing. But it is also the advent of Modernism that binds them. The exhibition, along with the catalogue essays, present Friedrich as one of the initial moments of Modernism and Richter as one of the most important and dynamic inheritors of that tradition. While this claim is not contestable in itself, what demands a response is the manner in which this exhibition avoids addressing how European Modernism is indelibly colored by a notion of Romanticism that provides the strictures for both conceptions of artistic personae (e.g., the gendered cult of genius and vision) and representations of the landscape (whether done naturalistically or abstractly). It is understandable that an exhibition should want to resist didactic and/or overreaching wall texts, but at the same time it seems illegitimate to coyly broach discussions of landscape and German national (or artistic) identity or “spirit” without giving the viewer a means to engage this conceptual history or at least to connect the nineteenth-century overwriting of the landscape with nationalist dramaturgy to contemporary cultural and political events.

Simply put, the “juxtaposition” of Friedrich- Richter succumbs to the frame of the exhibition itself: one that presents this work only in terms of–and here I am quoting from the wall text one is confronted with upon entering the exhibition–“similar strategies for landscape…[ones that are] evocative, resisting more dogmatic or theoretical approaches to art in pursuit of a more ambiguous and contemplative experience.” Is this articulated desire for a “more ambiguous and contemplative experience” of art not an uncanny return of Romanticism, one that transmits a spurious religious and political ideology through art? Are not the very concepts of Romanticism, naturalism, and even abstraction inherently “dogmatic and theoretical”? To avoid this discussion is to betray any critical remnant of Modernism that we may have inherited.

Gerhard Richter, Wald (892/11), 2005. Oil on canvas; unframed: 77 1/2 x 52 inches. Collection of Susan and Leonard Feinstein. Promised gift to The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © Gerhard Richter.

Besides the shortcomings of this “juxtaposition,” it is nevertheless interesting to play with other “juxtapositions” between Richter’s Wald and, for example, Gustave Courbet’s landscapes, which more clearly initiates a discussion of Modernism in terms of formal criteria and the pressing concerns of what we refer to as Post-Modernism.

Within and without this sublime frame, one could also consider Lucio Fontana’s works presenting his perspective on New York and Venice from the early-1960s. Richter’s latest series exists in a more dialogic relation to Courbet’s palette-knife landscapes or Fontana’s vertical slits cut through thin sheets of bronze (Spatial Concept, New York 10, 1962) than to Friedrich.

Lastly, it should be more well-known that Samuel Beckett often thought of Friedrich’s painting Two Men Contemplating the Moon (c. 1819) as he wrote his post-war drama Waiting for Godot (1954), a play that addresses the complexities of loss, representation, and identity–the concepts about which this exhibition falls noticeably silent. Perhaps we should remind ourselves of the last lines of Beckett’s play, which interrupt any art historical slide projector experience of Friedrich-Richter and expose our contemporary, nonplussed aesthetic and political predicament:

Estragon: I can’t go on like this.

Vladimir: That’s what you think. (…)

Vladimir: Well? Shall we go?

Estragon: Yes, let’s go.They do not move.4

Jae Emerling has been Chancellor’s Fellow in the Department of Art History at UCLA. He is the author of Theory for Art History (Routledge, 2005) and is currently teaching at Loyola Marymount University and Otis College of Art and Design.