Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel, installation view, New Museum, New York, September 26, 2018–January 20, 2019. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Au Naturel, the almost-thirty-year survey of the work of British artist Sarah Lucas, offers a witty send-up of the avant-garde savior complex at the heart of a self-righteous but flawed contemporary art world. Lucas systematically deploys high culture references combined with kitsch slogans in a manner seemingly designed to lambaste and offend, thereby impeding the processes of canonization implicit in the project of a retrospective itself. Lucas’s approach to sculpture is heavily indebted to established art historical precedents, particularly Hans Bellmer, Louise Bourgeois, Jasper Johns, Bruce Nauman, Senga Nengudi, Piero Manzoni, and Richard Serra. Yet the thrust of these frequent allusions is rude. Take, for example, Lucas’s so-called Muses (2015)—friends and intimates cast naked from the waist down, draped over dated, pedestrian furniture and appliances and posed with cigarettes perched delicately in their lady junk. The works function as a rhetorical up-yours to classed and gendered codes of decorum, not to mention as an affront to the denatured, disembodied canons of classical beauty on which the discipline of art history itself is in large part based.1 Extending this paradoxical appeal to her text-based works, photographs, and films, Lucas has effectively reinvented the genre of artistic satire by reframing the operational foundations of surrealist art. Her low-brow quotations demonstrate the degree to which the systems of reinvention and reconsolidation that underlie the dreamwork also form the basis for mass-media representation. The fundamental irony of Au Naturel is that nudity is always a cultural construct. In teasing this out (and I use the term teasing advisedly), Lucas indicts the feigned monumentality of a popular media that remains as inauthentic, partial, and compromising as ever.

Among the most engaging works in the entire exhibition are three otherwise unmanipulated photocopy blowups of actual pages of the British rag Sunday Sport, part of a group of early works that opened the New Museum’s second level. This suite of works on paper establishes the tone of the exhibition as a whole: deadpan surrealism understood in the contemporary sense of the term. This vernacular usage has more to do with the seeming impossibility of our own media-saturated reality than with formal biomorphism or the structure of the unconscious. It is a surrealism of unlikely conjunction, made manifest thanks to the disarming combination of individual complicity and journalistic impropriety. The Murdoch-era print media has furnished punchlines for headlines, but the indiscriminate public hunger for celebrity and fame seeking makes it impossible to distinguish precisely who (or what) is the butt of the joke.

Fat, Forty and Flabulous (1990) layers multiple entendres onto the notion of a newspaper “spread,” which is both pictured within the work in the fleshy expanse of the nude female body as well as embodied through the expanded dimensions of the resulting artwork itself. The piece narrates the story of a man named Reg Morris who, frustrated by his wife Elizabeth’s obesity, has offered his house for sale to anyone who would take her with it. The cruel gesture elicits a seemingly counterintuitive response from Bet, who unapologetically poses nude (“before we could stop her,” the author notes) and relishes the idea of a more sexually engaged partner. Readers and viewers therefore receive a taste of self-sanctioned spectacle. The titular pun is borrowed from Bet’s claim that she is “just as FLAB-ULOUS . . . as THOSE SKINNY LITTLE RAKES you see on the telly.”

This sordid twofer of woman and house is not just a grotesque media exploitation of a failed marriage. It is also a Louise Bourgeoisian conflation—woman (as large as a) house functions as a literal, post-feminist Femme Maison.2 This hidden pun exemplifies the continual play of reference—high and low, metaphysical and scatological—that runs through the entire exhibition. Translated into a working-class British idiom, however, it also demonstrates the anti-authoritarian nature of Lucas’s project. Fla-bulous conforms to what Sigmund Freud, in his study of humor, refers to as “condensation with substitute-formation.”3 This joke technique produces a composite word from two seemingly inimical entities. The resulting neologism flab-ulous, in its attention to norms of social comportment, recalls Freud’s initial example, “famillionairely.”4 Freud, who acknowledged the similarity between the processes implicit in such a joke and the psychic activity of the dreamwork (that is, the psychic manifestation of latent con- tent in altered form within the dream), took the tendency towards economy as the most general feature of any joke.5 Freud compares these verbal savings to the failed attempts of a housewife to economize, and it is precisely this economic failure that appears, both implicitly and explicitly, at issue in the testimonies of Reg and Bet.6

Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel, installation view, New Museum, New York, September 26, 2018–January 20, 2019. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

The sensationalizing headline and demeaning yet pithy epithets given to “ranting Reg” and his “marsh-mallowmound-missus” obscure the structural dimension of this marital distress. Morris is an ex-steel worker, and the decision to give his two-bedroom terrace away with the purchase of Bet’s “spacious rear” is a response to his difficulty facing mortgage repayments. The couple’s private breakdown opens onto a larger political reality—which the November 25, 1990, story conceals—of anti-inflationary monetary policy and economic recession that prompted, just three days prior, Margaret Thatcher’s resignation as Prime Minister. Lucas adopts the mechanism of the joke—what Freud deemed indirect representation or representation by its opposite—to expose an underlying systemic failure.7

Sarah Lucas, Fat, Forty and Flabulous, 1990. Photocopy on paper, 85 ¾ × 124 ¼ in. D.Daskalopoulos Collection. © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Fat, Forty and Flabulous also demonstrates the meaninglessness of the cliché of the searing exposé, a genre rooted in voyeuristic psychosexual appetites that can be redirected but never truly satisfied. There is, to begin, the seeming impossibility of the story itself. A quote from a neighbor, who has initially assumed that Reg’s for-sale advertisement was a spoof, ends the text, as if furnishing proof of the legitimacy of the whole tawdry situation. These assurances, however, do little to stave off the audience’s incredulity. Bet’s “heavy eating habit” seems to be symptomatic of her insatiability in the sack. Yet Fat, Forty and Flabulous also emphasizes in hyperbolic terms our own appetite for mass media, our need to see and scrutinize others, and our desire to make ourselves visual fodder in turn. It is as if, Lucas suggests, we ingest popular media headlines as hungrily and indiscriminately as burgeoning Bet does “CHIPS, CHOCOLATE or anything FATTENING.” Lucas’s jokework understands that indulgence is a psychic property and that consumers of mass media experience pleasure as the “relief from the compulsion of criticism” and of logic that it affords.8

Lucas’s rescaling of this moment of journalistic burlesque is indicative of her distinctive approach to artistic satire. Lucas replicates and amplifies rhetorical tropes of exaggeration and understatement. But in doing so, she also indicts the vacuity of the media itself. These transformations collapse the distance between the Sunday Sport, the height of hack, and its more reputable peers. In 1745, celebrated novelist and failed newspaper publisher Henry Fielding pointed to a shared origin for both the respectable and tabloid presses in language that mimics the emphatics of the Sunday Sport: “There is scarcely a syllable of TRUTH in any of them. If this be admitted to be a fault, it requires no other evidence than themselves and the perpetual contradictions which occur, not only on comparing one with another, but the same author with himself on different days. Second, there is no SENSE in them. Thirdly, there is in reality NOTHING in them at all. Such are the arrival of my Lord—with a great equipage, the marriage of Miss—of great beauty and merit; and the death of Mr—who was never heard of in life etc.”9 Thus Fielding’s major concern—frivolity—was also a minor one. Lack of proper proportion becomes a telling formal metaphor for the abdication of journalistic responsibility: a literal loss of integrity that renders all qualifiers meaningless. Here, at least, the press is in on the joke, hence their cheeky boast: “Sunday Sport always tackles BIG issues.”

Two other photocopy blowups from the same tabloid function as apt pendants to Fat, Forty and Flabulous. Sod You Gits (1990) profiles a little person stripper, named Sharon Lewis, who has developed a lucrative career as a topless kiss-o-gram. It is couched as a David-and-Goliath tale, with a whip-toting Sharon as the unlikely hero, accompanied by her forbearing, and also rather petite, hubby Paul. Certainly, Sharon is not a typical example of women’s lib, though the tagline “plucky pint-sized housewife battles against cruel shitheads who call her a penguin” casts her as a crusader of sorts. The suggestive images of Bet and Sharon fetishize opposing bodily extremes, big and small, while simultaneously spoofing the language of empowerment of an earlier generation of feminists. The stories purport to transform public humiliation into personal pride, yet the ribald language in which they are couched forces the question of whether they do so at the expense of their subjects’ dignity. Sharon’s meagre victory illustrates the constant shift between the inane rendered grandiose and the great rendered insignificant that is operative within Lucas’s work. Lucas edits and enlarges such contradictions—the literary acts of condensation and displacement at the heart of the mass-media surreal.

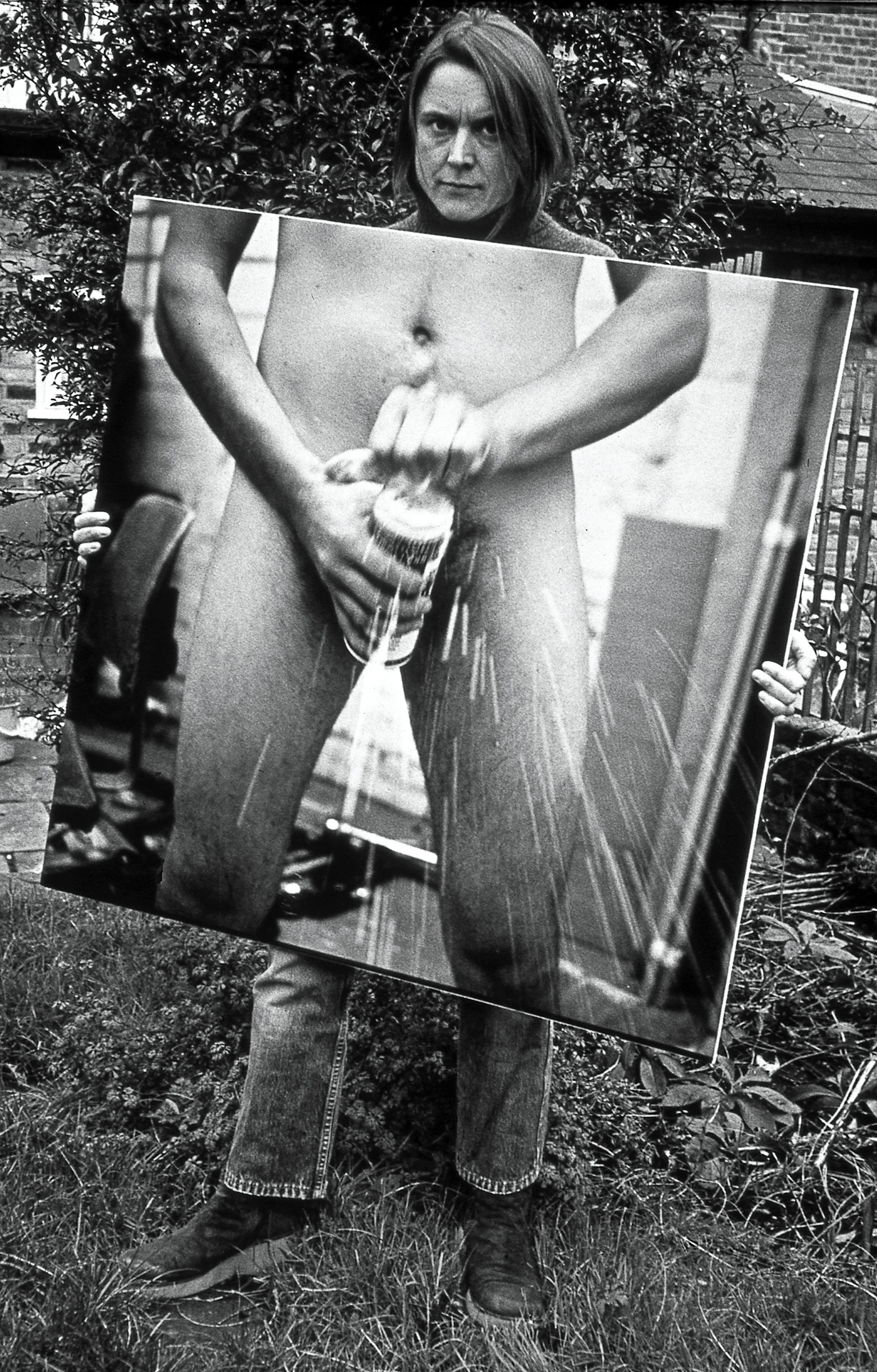

Sarah Lucas, Got a Salmon on in the Garden, 2000. Black-and-white photograph, 69 ½ × 46 ¼ in. © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Appearing frequently in photographs that line the galleries and encompass entire walls, as well as in the promotional images for the exhibition, the androgynous appeal of Lucas herself functions as a framing device for the New Museum’s presentation. Yet Lucas’s self-display feels impersonal and removed, a reality arising from the fact that Lucas’s so-called “self-portraits” were not actually photographed by the artist herself.10 Lucas is shown smoking a cigarette, eating a banana, or wearing a shirt that proclaims “selfish in bed.” She stands fully-clothed in a garden, holding a larger-than-life-size photograph of a nude male figure opening a beer can in front of his genitals to create a mise-en-abyme, as if to say, Luncheonon-the-Grass-my-arse (Got a Salmon on in the Garden, 2000). She gazes intently at the viewer she cannot see, as the viewer in turn looks to representations of the artist that are averted or obscured. Sexuality is visualized through pithy analogs (fried eggs, dead fish, utility nipple hole in a tatty t-shirt). The pedestrian nature of the tasks she performs and her refusal to make her own body an object of display or comment generate a sense of unfamiliarity with Lucas as a subject and demarcate the body of her work from that of her former collaborator, Tracy Emin. Whereas Emin “sells her memories,” feigned as they may be, Lucas’s work is transactional without being diaristic.11 As often as she is seen, and as directly as she looks back at us, she evades the gaze. Lucas’s presentation has been celebrated for her refusal of gender norms (particularly those associated with women artists) and for her experiments with a defiantly androgynous persona.12 But it is equally interesting for the degree to which it upsets the typical expectations of acute observation, self-explication, and psychological interiority associated with self-portraiture as a genre and with feminist art in particular.

Tucked into a corner of the fourth floor is Lucas’s Sausage Film (1990), an eight-minute video that exaggerates the droll impersonality of her photographs and encapsulates the blasé, media-induced absurdity that makes her oeuvre so appealing. In the film, Lucas peels and eats, awkwardly, with knife and fork, a sausage and a banana. The opening seconds show Lucas seated at a table as a topless male server delivers her first plate of dry, thoroughly unappetizing sausage. There is a sense of comedic brinksmanship, as Lucas and the viewer simultaneously attempt not to laugh at the inanity of this conceit and, by extension, the pornographic mise-en-scènes that inspired it. Lucas has completely deprived the interaction of all sensuality—and indeed her literal presentation functions to undermine the staid conventions of pornography as a genre. But, as elsewhere, Lucas’s Sausage Film is also a broader reflection on the media and the cultural history that has produced it. In the opening sequence, Lucas is shown holding the utensils upright in her clenched fists, a pose denoting crass manners recognizable from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British satirical prints. In such representations, sausages (along with eggs and sauerkraut) were an index of Germanness—deployed both in sendups of ill-behaved Hanoverian monarchs and as a warning against foreign influences (potentially emasculating and simultaneously boorish) in British political and cultural life. Lucas picks her teeth with her knife; nevertheless, her manners do not rise to the level of carnivalesque intemperance such satires usually portray. And yet, a “sausage film” is by definition impolite. In emphasizing the very pedestrian and unerotic nature of a putatively smutty film, another instance of representation by its opposite, Lucas subverts the judgments embedded within the structure of the genre of pornography itself.

Sarah Lucas, Sausage Film, 1990. Video still. Betacam SP video, sound, color, 8:20 min. © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

James Gillray, Germans Eating Sour-Krout, 1803. Hand-colored etching on wove paper, 10 2/3 × 15 ¾ in. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The degree to which the Sausage Film reminds us of how women’s consumption is fetishized and policed brings the viewer back to our initial encounter with the fat tabloid star. The film closes the exhibition with neat thematic circularity, while also generating suggestive allusions to works in other areas of the museum. In particular, the Sausage Film reads, albeit anachronistically, as a response to the question posed by Dynasty Handbag (the performance alter ego of Los Angeles based artist Jibz Cameron) in her 2017 video Vat Do You Vahnt for Bwekfas?, screened concurrently in the New Museum’s basement staircase. This consonance was certainly intentional on the part of the exhibition’s curators, Massimiliano Gioni and Margot Norton. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the exhibition is the degree to which Au Naturel functions as one proposition out of several competing reappraisals of contemporary surrealism staged by women artists concurrently throughout the New Museum—from Dynasty Handbag’s hysterically zany sendups of daily life in a compromised and compromising post-capitalist landscape to the gorgeously grotesque, technologically dystopian film Blood In My Milk (2018), by Marianna Simnet, and the aqueous biomorphic sculptures of Marguerite Humeau.

Sarah Lucas, 1-123-123-12-12, 1991. Boots with razor blades, 63/4 × 4 × 107/8 in. each. Private collection. © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel, installation view, New Museum, New York, September 26, 2018–January 20, 2019. Courtesy of the New Museum. Photo: Scott Rudd.

Lucas’s work is characterized by a certain wariness. She displaces direct signification into her chosen vehicles, lest one reading become too available, too dominant. She is skeptical of an art that is too easily annexed to the false monumentality of ascendant fascism, just as she was cutting, in the tabloid images, toward the demise of Thatcherite neoliberalism. The transformation of one of Lucas’s favored motifs, the isolated pair of boots, exemplifies this stance. Of the various pairs of boots dotting the exhibition, several are (or are cast from) boots the artist owned and wore herself. This group includes one actual pair of Doc Martens embedded with concealed razor blades in the toes (1-123-123-12-12, 1991), a work that courts myriad references to Lucas herself and to her distinguished artistic predecessors. In a famous series of essays, the art historian Meyer Schapiro rebutted the philosopher Martin Heidegger’s claim that “a painting of shoes by [Vincent] van Gogh expresses the being or essence of a peasant woman’s shoes and her relationship to nature and work,” instead asserting, “They are the shoes of the artist, by that time a man of the town and city.”13 Schapiro, refuting Heidegger’s imputed, implicit masquerade, links the worn boots with van Gogh’s experience of journeying on foot from Holland to Belgium and defines them as a relic of the self.14 Lucas, too, has emphasized walking in the city—an experience necessitated by her own poverty (and, by extension, the broader economic collapse that produced the phenomenon of the YBAs) and the curfews imposed by the London transit system—and the insults she received for wearing ungainly, mannish footwear.15 The razor blades embedded within the boots speak to the danger Lucas herself confronted as a working-class woman perambulating East London in a period of recession, underlining class as a structuring category of experience. But the razored boots can also be read as a potent symbol of non-conformity, reinforcing an understanding of “queer” subjectivity that, in the early 1990s, was particularly fluid and not strictly linked to sexual identity.16

Considerations of queer identity and cultural hegemony are magnified in the monumental kinky boots that occupied the New Museum’s ground floor. Created especially for the New Museum, the 11-foot-tall high-heeled platform boots of Vox Pop Doris (2018) are based on a 2013 work, Jubilee. The title suggests a certain widespread cultural acceptance and celebration—a mainstreaming—of the kitschy, femme culture that the boots themselves exemplify. No longer symbols of economic and cultural dislocation, Lucas’s new style of boot points to a partial and arguably misbegotten form of recognition. Queer identity has become acceptable, in so far as it embodies pop culture spectacle and conforms to hyperbolic presentations of basic stereotypes of femininity. Vox Pop Doris plays on Latin words for “voice of the people,” a term that raises the specter of fascism and populism as much, if not more, than democratic reform. The recognition that queer aesthetics have been coopted by white nationalists and alt-right performers like Milo Yiannopoulos to reinforce patriarchal institutions and attitudes, and the historical fact that well-regarded minimalists like Robert Morris flirted with the aesthetics of fascism, give the work a sinister, deeply political edge.17

Sarah Lucas: Au Naturel, installation view, New Museum, New York, September 26, 2018–January 20, 2019. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Sarah Lucas, Christ You Know It Ain’t Easy, 2003. Fiberglass and cigarettes, 77 × 72 × 16 in. © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Eroticism and the exercise of power is ultimately the prevailing concern in Lucas’s work, and it links the artist’s interest in the popular press with larger issues of public memory. On the fourth floor of the exhibition, as if reveling in triumphantly toxic blokiness, a massive wall mural depicting Sarah Lucas reclining on marble steps appears behind a group of car sculptures adorned with giant penises and cigarettes and adjacent to a cigarette-covered crucifix. Referencing various forms of contemporary idolatry, the installation draws on fascist theatricality and ritual, orchestrated around the cult figure of the ruler. Not coincidentally, the setting of the Lucas photograph Divine (1991, a pixelated detail of which serves as the exhibition catalog’s cover) is recognizable from another work in the exhibition (Mussolini Morning, 1991) as the Stadio dei Marmi in Rome’s Foro Italico, formerly Foro Mussolini, one of Benito Mussolini’s major accomplishments in urban planning. The Foro Mussolini was a showpiece of the regime that linked the cult of the body and physical strength with imperial Rome.18 It was a central plank in Mussolini’s program of romanità, or Roman-ness, intended to create a galvanizing vision of the past around which his new Italy would be organized.19 The Foro Italico remains a major destination for contemporary athletic spectacle in the Eternal City. In the New Museum installation, Lucas, Gioni, and Norton have added layers of veiled historical symbolism: the fourth floor restages the Chapel of the Martyrs in Mussolini’s darling 1932 Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution, evoking the flames of martyrdom not by a blazing-red metal cross, but rather a cigarette-studded crucifix and the wrecked remains of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s midnight joy ride.20

The rhetoric of monumentality is central to the current climate of rightwing extremism. At stake in the white nationalist movement is the very definition of power in the Roman sense as the ability to punish and remember. Part of the appeal of Augustus for Mussolini (who began his career as a newspaper editor) was the effectiveness with which he consolidated his auctoritas—clout or influence—which included the power of life or death over his subjects. When, in 1939, the historian Ronald Syme published his history of Augustus’s reign, The Roman Revolution, it offered a not-so-thinly-veiled warning to apologists for fascism. He wrote: “When the individuals and classes that have gained wealth, honours and power through revolution emerge as champions of ordered government, they do not surrender anything.”21 Augustus’s corresponding erasure of individuals from the historical record through the act of damnatio memoriae, which Mussolini reenacted through relocation and restaging of Augustinian monuments, including the Ara Pacis and the tomb of Augustus, buttressed a self-serving narrative of “alternate facts.” As Lauren Ginsberg has pointed out, alt-right organizing around the preservation of civil war monuments is another chapter in this struggle to define public memory.22 Today, violence inflicted against counterprotestors represents punishment, an attempt to enforce desired cultural norms that thwart legal definitions. In a similar vein, Lucas’s insult lists, on view elsewhere in the exhibition but also created while residing in Rome, detail the verbal mechanisms through which nonconformity is proscribed.

Lucas’s monumental boots and her colossal self-image replicate the exaggerated cult of hero worship coincident with fascist ideology. The boots are coded in a particularly swish contrapposto, one reminiscent of looking up at the muscular buttocks of the Stadio dei Marmi marmi from below. This distinct viewpoint, which conflates fascist aesthetics with homoeroticism, was gleaned from Lucas’s Italian sojourn in the early 1990s, during a historical moment of economic contraction and recovery that we are reliving today. The boots play on familiar rhetorical devices of hyperbole and understatement, but translate them into an expanded, political register. In doing so, they draw on the surreal aspects of the impossible conjunction that is “popular memory.” After all, damnatio memoriae can best be understood as a historical act of condensation and displacement—a substitution of one reality for another. Sarah Lucas’s feminism is perhaps most interesting because it has so little overt relationship with the movement as a political entity and so much to do with the larger problem of domination in all its political, historical, and cultural forms. So the answer to the question raised by The New York Times—“Is Sarah Lucas Right for the #MeToo Moment?”—may not be that the artist “shows us what it’s like to be a strong, self-determining woman.”23 Rather, Lucas represents feminism by its opposite, casting herself as the manspreading, phallus-usurping feminazi enjoying her “monumomentary” success while diffidently overlooking the smoldering ruins of modernism’s dead and dying idols. Now that’s a pretty tight joke.

Leslie Cozzi, FAAR’18, is the Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Author’s Note: I am grateful to Melissa Ragain and Lauren Ginsberg for their bibliographic suggestions.