Speculative fiction writer and visionary Arthur C. Clarke first cited his “Third Law” in the essay “Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination.” The concept describes the interpretation of specialist knowledge by the uninitiated public, positing that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”1 While an easy interpretation of this principle might set the spiritual in opposition to the technological, the work of Jimmie Durham prompts consideration of how we might understand both technology and magic a little differently and still apply the same principle. Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World is the first solo presentation of the artist’s work in the United States since 1994. While much has changed in the US art world since then, Durham’s exhibition suggests there is still more work to be done in challenging the simplistic narratives and easy assumptions that are too often hung on artists of color.

As an artist and an activist, Durham experienced an awakening while studying abroad at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1973, when American Indian Movement (AIM) activists in the United States initiated a three-year occupation of the Pine Ridge Sioux reservation at Wounded Knee. He consequently left school and returned to the United States to take up a role in the movement, organizing Native Americans and indigenous peoples globally. AIM was founded as an outlaw movement, meant to operate in opposition to a legal system that seemed rigged against its constituents. Durham is artistically rebellious, long known for his unwillingness to be defined, whether ethnically, geographically, or stylistically. Durham developed and led the organization’s International Treaty Council, a body that continues to coordinate indigenous communities worldwide in advocacy for their rights to land, cultural expression, and a dignified quality of life. Durham’s organizing work with AIM and Treaty Council has had long-lasting impact, as evidenced in the confluence of international groups currently fighting in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Foregoing a nationalistic and oppositional approach in favor of an international strategy of engagement with various political and legal systems to make change, Durham came to diverge politically from other AIM leaders. Though he ended his involvement in both AIM and Treaty Council around 1980, this tension between engagement and opposition, as well as the outlaw spirit of these formative years, continues in many aspects of his work as an artist.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 29– May 7, 2017. Photo: Brian Forrest.

In a conversation at the Hammer Museum between University of California Los Angeles art historian Miwon Kwon and Whitney Museum curator Elisabeth Sussman, At the Center of the World curator Anne Ellegood raised some of the prevailing narratives that persist about Durham’s work.2 One is that Durham’s activism ended at the time when his art career resumed, thereby separating the artist’s politics from his studio practice in a way that makes him more palatable to arbiters of official history. Another has it that Durham was heavily invested in questions of identity prior to the watershed 1993 Whitney Biennial, which Sussman co-organized and in which Durham participated. Many assume that he subsequently abandoned this interest in favor of formal, material, and architectural concerns on his return to living in Europe in 1994. These assumptions are predicated on certain preconceived notions: one is either an artist or an activist; identity is something one either obsesses over or ignores; and artists of color who assume a subject position in their own work are working from autobiography rather than allegory.

Cherokee, American, internationalist, artist, activist, poet, trickster, contemporary, ancestor—Durham performs these conflicting expectations in order to deflate them. For example, a work in the exhibition from 2009 is titled Upon reflection, I was no longer sure of my position. Not articulating a sure position allows for the possibility that the artist of color could be working from a complex sense of self at all times. In the sculpture, a large hunk of shiny black obsidian sits opposite a similar mass of “German silver,” an alloy of copper, zinc, and nickel with a blond, golden sheen, atop a steel frame table. A small obsidian mirror faces the table lengthwise. As installed at the Hammer, it is impossible for the viewer to see oneself reflected in the mirror. Each point within the whole represents a possible position. Other recent works use handmade obsidian knives to cut away at drawing and sculpture materials. Durham’s use of razor-sharp, primordial obsidian references ancient technologies, but it also represents the artist’s incisive language, piercing intellect, and cutting humor.

Jimmie Durham, Upon reflection, I was no longer sure of my position, 2009. Obsidian, German silver (copper, zinc, and nickel), steel table, obsidian mirror with colored tin frame. Mirror: 13 1⁄2 × 10 × 3⁄4 in. table: 39 1⁄2 × 197 × 23 1⁄2 in.; obsidian: 18 1⁄2 in. diameter; German silver: 17 3⁄4 in. diameter. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Purchase. Courtesy of kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

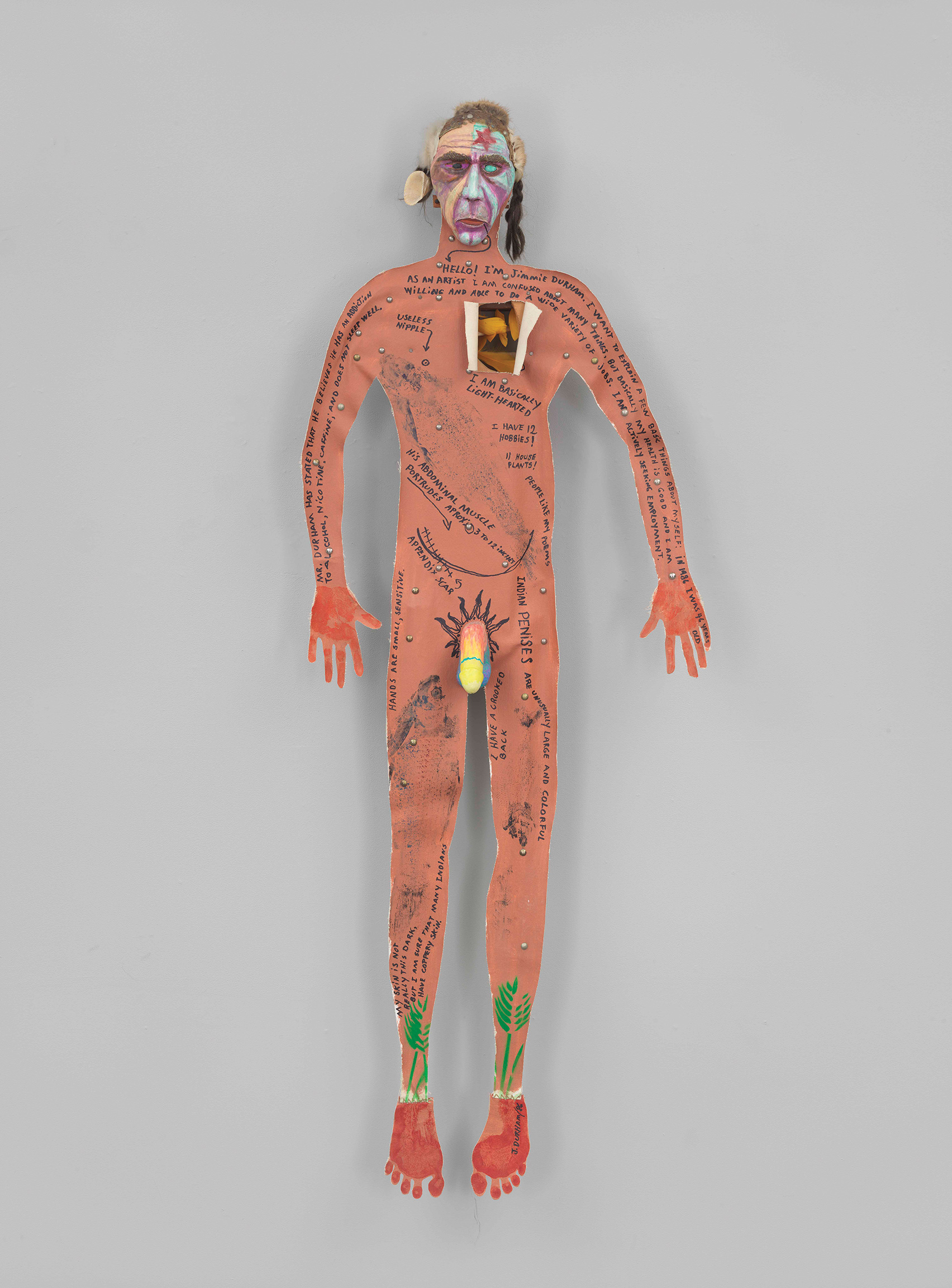

Sharp, black comedy pervades the exhibition. Like the best comedians, Durham employs both verbal and physical humor to address real political and historical issues, such as violence and its consequences. Language can be a punchline, but so can color and material. In Self-Portrait (1986)—a life-sized silhouette of the artist—the conceptual artist’s disdain for autobiography is gleefully skewered. Having reduced his self-representation to a set of stereotypes about Indians, Durham now systematically embraces or rejects them. Materials commonly associated with Native Americans, such as tanned hides, seashells, and braids, reinforce the stereotypic framing and thereby deepen the subversion. Durham writes in laconic block printing over a deep reddish brown background cut to his shape: “Mr. Durham has stated that he believes he has an addiction to alcohol, nicotine, caffeine [sic]; and does not sleep well.” This reflects common prejudices about Indians, but also could describe any New Yorker, as Durham was at the time. Color is the kicker. “My skin is not really this dark,” he inscribes on one shin bone. “But I am sure that many Indians have coppery skin.” Material is a pun. “I am basically light-hearted,” reads one note, with an arrow pointing to a space in which the artist’s “skin” has been cut away to reveal a cloud of yellow feathers where his heart should be. It’s a disarmingly sweet moment in a show that feels forged in the fires of the artist’s disillusionment with both cultural and political institutions.

Other works from the early 1980s to the early 1990s use found bones, including animal and human skulls. Durham has said that in these works he was trying to “understand what each particular animal (I mean the individual not the generic) feels about being dead.”3 The individualism of each sculpture is a gesture against the flattening of a community of “Native Americans” into a symbolic entity. The dead among the living is a theme to which Durham consistently returns, as if teasing out a hauntology of Native philosophy and tradition from within our glib consumption culture. For Jacques Derrida, who coined the term, haunting transpires whenever an echo of the past manifests in the present, as a re-experiencing rather than a remembering. Capitalism is haunted by the potential commoditization of every object of use, which infuses each form with a foreboding of its eventual reduction to exchange value alone, even before the act of disassociation that turns a religious totem into an art object, for example, is realized.4 For postcolonialists following in Derrida’s wake, haunting becomes the last vestige of resistance that remains to represent a decimated people in the culture of their conquerors. As described by British cultural critic Mark Fisher, hauntology is enacted by postcolonial artists through pastiche, unexpected juxtapositions, and reiterations. “Haunting,” according to Fisher, “can be seen as intrinsically resistant to the contraction and homogenization of time and space. It happens when a place is stained by time, or when a particular place becomes the site for an encounter with broken time.”5 Durham’s sculptures force such an encounter. They are accursed—dead while still alive, contemporary yet mired in the traumas of the past—and the encounter is not an easy one. These extremely beautiful objects, painted in rich colors and decorated with feathers and semi-precious stones, are both desirable and hostile.

Jimmie Durham, Self-portrait, 1986. Canvas, cedar, acrylic paint, metal, synthetic hair, scrap fur, dyed chicken feathers, human rib bones, sheep bones, seashell, thread. 78 × 30 × 9 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee. Digital image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

Resisting traditional or commercial expectations for Native American art, Durham uses the contemporary post-conceptual visual art tropes of the social, the phenomenological, the monumental, and the mystical to deflate institutional authority and to communicate revolutionary ideas to a contemporary, media-savvy audience numb to the traditions and the political theater of previous generations. AIM founder Russell Means famously said that, while he refrained from writing out of adherence to the oral traditions of the Lakota, he was “concerned with American Indian people, students and others, who have begun to be absorbed into the white world through universities and other institutions.” Thus he consented to having his words written down and published to combat “the process of cultural genocide being waged by Europeans against American Indian peoples today.”6 While Means, whose nationalist politics prompted Durham’s departure from AIM around 1980, had a very different worldview from the cosmopolitan artist, his words here indicate why one might not be so quick to write Durham off as an activist just yet. Durham uses the language and institutions of contemporary art to put ideas about indigeneity and contemporaneity in front of audiences, including young indigenous people, who care more about the present than they do about the past.

Activism in art is often connected with collectivism and acts of sharing of knowledge and/or resources, as in the radical theater of Durham’s touch-stone, Augusto Boal. Generosity has been a recurrent theme in Durham’s practice since the early 1970s. Before Felix Gonzalez-Torres was making takeaways and Rirkrit Tiravanija was serving meals in the gallery, Durham was engaging in projects like Little Black Things (1971), at Circa Gallery, in Geneva. In this work, each art object was priced at “minus one cen-time” such that a sale would leave the buyer richer by an artwork and an extra penny.7 In Manhattan Festival of the Dead (1982), Durham adorned a Day-of-the-Dead-style altar with brightly painted skulls in “an honoring ceremony of those people…in New York who have been killed by subways, .38 slugs, needles or desperate acts, without any proper ceremonies to help their passage and our passage.” Rather than sell the work, which the artist has expressed feeling conflicted about, he frames the ceremony as “a traditional Cherokee give-away, but since this is a Manhattan ceremony the give-away will cost you $5.” At once Durham references the origins of New York as Lenape tribal land, “purchased” for the equivalent of $24 from a people who understood only gift and barter economies; and the ruthlessness of the city’s capitalist hustle, which extends to the city’s artists of color, who must endlessly re-perform their stolen heritage in order to make ends meet.

Included in Manhattan Festival of the Dead and on view in the Hammer exhibition is Karankawa (1982), a human skull inlaid with turquoise, shells, feathers, and carvings. To see a real human skull in an exhibition of contemporary sculptures seems shocking, yet human remains, including skulls, are commonplace in museum collections and displays of Native American art. Karankawa is made from a skull that Durham found on a beach in Texas where a historic Indian massacre took place. Durham’s work with skulls expresses the fury and the majesty denied to those ancestors whose bodies have become the cultural property of the colonial power.

Jimmie Durham, Karankawa, 1982. Human skull, cedar, seashells, abalone shell, alabaster, beads, button, turquoise, cow leather, fish bone, parrot feathers, woodpecker feather, two deer teeth, white and black ink, 19 × 9 × 9 in. Collection of Robert Cantor and Margo Levine, New York. Courtesy of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Adam Reich.

In this work, Durham exploits expected material tropes of native art, such as semi-precious stones, beads, and bleached skulls (a fixture of Southwestern decorative painting), but he infuses his assemblages with an uncanny aliveness that produces palpable discomfort. He soon became frustrated with the experience of working in the United States, where his insistence on identifying as a contemporary artist rather than an indigenous one while still focusing on his Indian culture continues to pose an overt challenge to curators and critics working within prevailing political and cultural systems. United States history is built on a myth that the land of this continent was for the taking. This narrative requires Indians to be long-dead in order to be legitimate. Living Indians who are urbane and culturally contemporary disprove the premise that Indians do not, and cannot, belong to the modern world.

Within communities that have been forcibly separated from their histories, efforts to restore cultural connection can be hampered by the effects of this erasure. Which elements of the culture have been preserved and studied, and whose version of events has been incorporated into history, will be determined by their relative usefulness to the colonial power. Since the national story requires Indian cultures to exist in the past, much of what is known even by Indians is anchored in a version of indigeneity that is rooted in pre-industrial lifestyles. In the United States, Durham frequently came up against the expectation of fellow Native Americans and Americans of other backgrounds that authentic cultural expression for a Cherokee artist would require use of traditional techniques and motifs. Durham’s resistance to this type of practice is informed by historical precedents such as Ishi, the Yahi tribesman who was “discovered” by University of California Berkeley anthropologists in 1911 and brought to live in a museum as a living monument to his decimated tribe. Rituals and technologies that evolved out of practical and social contexts became mimetic actions, a performance of living that was instead a kind of death.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 29– May 7, 2017. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Durham is no doubt aware of this history when exhibiting his work within the context of a museum that is part of the same University of California system, which continues to maintain study collections of indigenous human remains, despite repatriation challenges from recognized Indian tribes. This knowledge may provoke the viewer to respond differently to works made from animal and human remains in the exhibition. Durham identifies as Cherokee, but he is unwilling to allow the United States government to “recognize” him as a member of a tribe, thus foregoing access to the limited support allotted on this basis.8 Even the terminology is suspect. “Indian” is derived from the Spanish (“in dio”) and anecdotally associated with Columbus confusing the New World for the Far East. “Native American” legitimates an “America” that excludes the Americas—another non-starter. Durham uses both terms when referring to himself, though he uses “Indian,” the moniker politicized by AIM, more frequently. This may reflect his generational position or his identification with the activist over the academic.

Questions of exclusion and legitimacy are ongoing in Durham’s work. Consider the pair of sculptures titled Cortez (1991–92) and Malinche (1988–92), which are among the first of his large-scale works. The sixteenth-century Spanish conquistador and his indigenous Mexican translator and concubine are a study in contrasts. Cortez’s pale face tops a standpipe body and a plow carriage base, suggesting a machine that tills soil into profit. He is made of industrial materials, including found steel, and PVC. One gloved hand droops aimlessly while the other is a tangle of rebar. He is hard, sharp, and confident. While Cortez stares nobly into the distance, Malinche’s affect is more ambivalent. Her form is mostly organic, made from wood, cloth, and paint. She sits demurely with her hands in her lap, one carved foot resting primly next to the other, which is shaped from a lump of dirt and straw. This earthen foot suggests her connection to the soil of her birth, as well as her fall from grace. Her torso is made of found and carved wood, sticks, and chair parts. A gold lamé bra droops from her shoulders. Her body seems assembled from a combination of indigenous and European elements, with a Gothic feel to her mismatched hands and feet, reminiscent of a medieval German crucifixion, often made from a similar soft wood. Durham uses guava wood, which is indigenous to Mexico and grew close to Durham’s home in Cuernavaca.9 Feathers and beads adorn the celebrated beauty. Her lips bear a hint of pink, and the expression on her carved face reads between mournfulness and shame. One eye fixes on the viewer; the other is darkened behind a sheath of serpent skin. Is she longing for her absent people? Or ruminating on their rejection of her unmanageable qualities? Is she a symbol of complicity in the colonial project or an emblem of transcendence? Conflicting impulses play out on her body and in her adornments. Durham shows his capacity for naturalism in her features but also employs other means of using his materials to get his point across.

Jimmie Durham, Malinche, 1988–1992. Guava, pine branches, oak, snakeskin, polyester bra soaked in acrylic resin and painted gold, watercolor, cactus leaf, canvas, cotton cloth, metal, rope, feathers, plastic jewelry, glass eye, 70 × 23 5⁄8 × 35 in. ©S.M.A.K. / Dirk Pauwels. Courtesy of Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium.

Jimmie Durham, Cortez, 1991–92. Fiberglass and resin, PVC, metal car parts, leather, glass, acrylic paint, rebar, sheet metal, pulleys, handles, 88 1⁄2 × 57 × 20 1⁄2 in. ©S.M.A.K. / Dirk Pauwels. Courtesy of Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (SMAK), Ghent, Belgium.

Malinche is a complicated figure in indigenous Mexican lore. Born between Aztec and Mayan-controlled territories, she is caught between identities and loyalties. Malinche entered Cortez’s circle as a slave, but her exceptional beauty and her skill with languages promoted her to insider and confidant. Abandoned by her own people—the mother and stepfather who gave her away and the Tobascan clan that sold her to the Spanish—she becomes his native informant. Malinche is also the mother of Cortez’s son Martín, and thereby the symbolic mother of the mestizo or mixed European-indigenous Latinx people. Despised by the revolutionary nationalists of the early twentieth century for what they took as her lack of agency or loyalty—her abjection—Malinche has in recent decades been reclaimed by some Third World feminists, who hear echoes in her story of their own subjugation by men on both sides of the struggle. Writing in 1980, Chicana literature scholar Cordelia Candelaria’s essay “La Malinche, Feminist Prototype” helped to position her as a cultural symbol of la mestizaje, representing the mixed-blood indigenous-European heritage of a majority of Latinx peoples. Rather than a traitor, Malinche becomes a hybrid, occupying a space of political visibility otherwise reserved for men through her association with the conquistador. As a political operator, Malinche’s opposition to the rule of the Aztecs who had enslaved her had been total, and her cooperation with the Spanish colonizers is thereby justifiable, despite their racial dissimilarity. As an enslaved person, her agency is not guaranteed. On the question of shame, Candelaria notes, “She would have brought shame to the cacique of Tabasco and to her adopted people, had she not obeyed and served as best she could.”10 Durham’s Malinche is the poster image for this exhibition, reproduced three stories high on the Hammer façade, and it is tempting to think she represents Durham’s own rejection of Indian nationalist political thinking after 1980.

Under colonialism, technology has been the wedge used to differentiate the savage from the enlightened man and to manipulate allegiances among preexisting communities in a region to enable conquest. Technologies that have been used in this way include language and writing, currency, craft, photography, and agriculture, as well as the digital technologies of the present. Access to those technologies connotes advantage, and their lack connotes disadvantage, with a moral judgment attached. Durham’s distinctive approach to sculpture is informed by both official and unofficial technological knowledge. He attended the art school in the 1970s, worked construction jobs in the 1980s, and also learned carving and handworking from his father as a child. “Everybody in my family carved and made things,” explains Durham.11 His ideas about pedagogy and access to technologies and ideas are also informed by the influence of the Brazilian thinkers Paolo Freire and Augusto Boal, with whom he studied and talked.

Durham draws from both craft and anti-art discourses, combining careful and thoughtful making with subverted expectations of the value and integrity of objects. In Still Life with Stone and Car (2004), a performance in Sydney, Australia, that is reproduced as a large poster on the museum’s exterior, Durham uses the most elevated sculptural material in the classical hierarchy—stone—as a tool of negation used against symbols of human achievement. Using a large construction crane, he lifts a massive boulder high above a red Ford Festiva, and brings it crashing down. When the destruction is wrought, he paints a simple cartoon face onto the boulder. This is a technological achievement: a primal gesture that ironically requires heavy equipment to enact. As explained by philosopher Alva Noë, “Art is not a technological practice any more than choreography is a way of dancing. But art presupposes technology and can be understood only against that background. Just as choreography is preoccupied with the fact that we are organized by dancing, so painting (say) responds to the fact that we are organized by pictures (or by techniques of picture making and picture using). Pictures, crucially, are a technology, and picture making and picture using are organized activities. And so these are raw materials for art.”12 Noë stipulates that what differentiates the artist from the technologist is the artist’s capacity to use these technologies to produce constructive failures rather than march toward heroic ideals. Dropping a stone, like drawing a pathetic “face” on the boulder that he drops, is a way for Durham to reassert the power of the human in alignment with nature, against capitalism and industrial resource exploitation. The gesture simultaneously deflates the artist’s own ego, foregrounding his technical limitations as a sculptor. This seemingly infantile gesture in fact employs artistic, linguistic, and cultural technologies to articulate a complex subject position within the work.

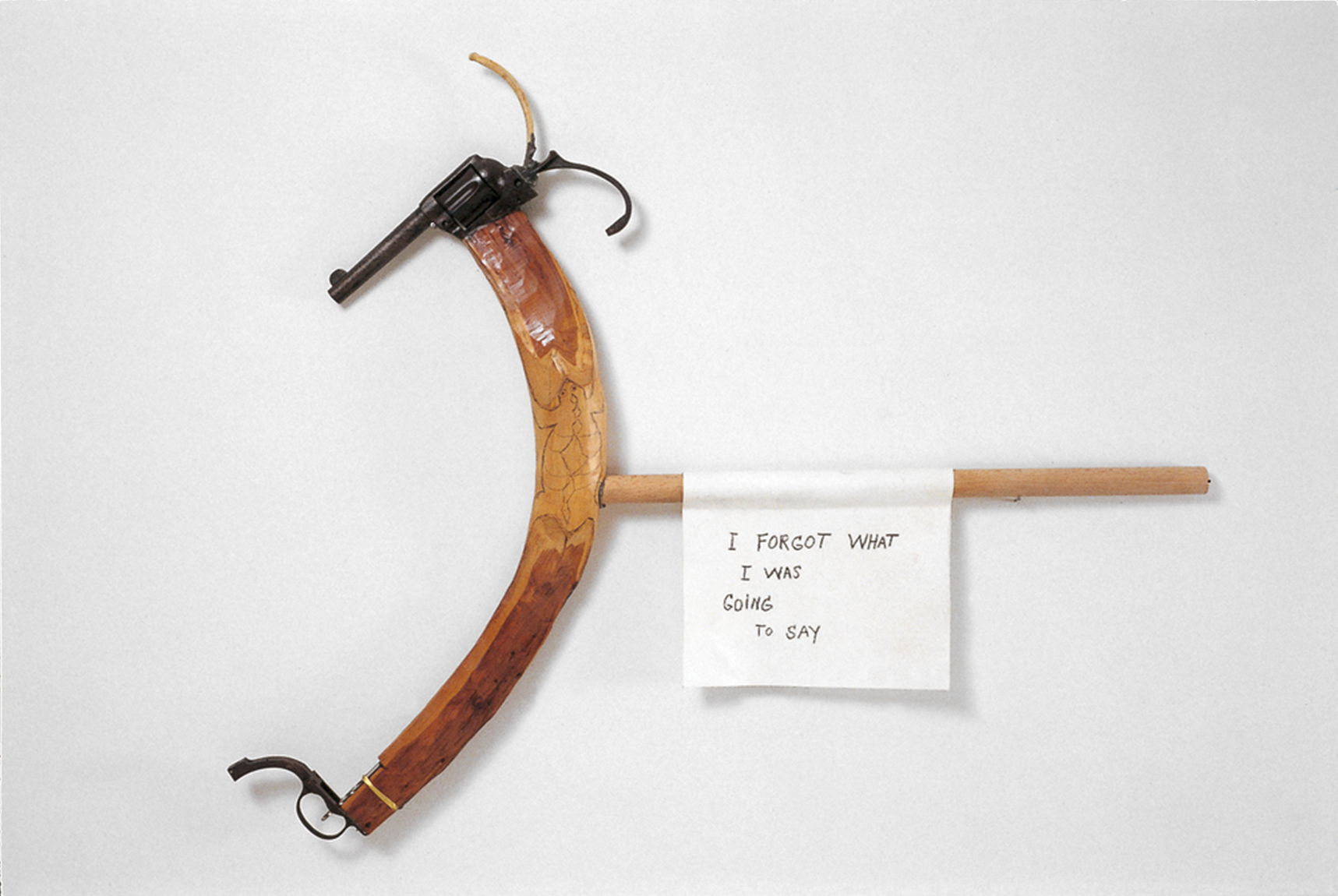

Durham’s technical facility with materials and aesthetics is matched by his ability to charge a space with emotional energy carried in the objects that he creates. Sometimes the most simple or mundane gestures carry the most charge. Hommage à Filliou (A Piece of Wood Sculpted by a Dog, Painted by a Human. A Piece of Wood Sculpted by a Machine, Painted by a Human) (2003) presents the titular two pieces of wood, side by side. One is a near-perfect, elongated cube, the other a mangled irregularity. Both are painted gold to reflect their elevated status as artistic and metaphysical objects and their commensurately elevated value. This simple act of comparing and equalizing mankind’s warring impulses toward the animal and the machine is rich in visual poetry, befitting its dedication to Robert Filliou, the Zen trickster of the Fluxus generation. I Forgot What I Was Going to Say (1992) dissects and inverts a handgun into a gesture of formal impotence. Creating meaning from such provisional materials and methods seems a kind of alchemy. A Pole to Mark the Center of the World in Berlin (2004) is a whittled branch, mostly straight and standing 711⁄2 inches, comparable to the height of an adult male. Attached on a braided wire is a handheld mirror, with which one might re-center one’s individuality and be reminded of one’s merits when buffeted by the self-assuredness of northern Europe. The pole can, of course, be placed anywhere, questioning who holds the power to determine center and periphery, and whether that power can be seized. Durham has made several such poles, each one tied to a specific geography which the works propose to reorient, with the bearer always at the center.

Jimmie Durham,, I Forgot What I Was Going to Say,, 1992. Metal gun parts, yew tree from Ireland, wood dowel, bone, acrylic on canvas, 24½ × 26½ × 2½ in. Collection of Dieter & Birgit Broska.

The globe is in fact being reoriented, with power shifting away from the United States and Western Europe into emerging markets and developing industrial zones in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Durham’s outsider position in Europe provides a vantage on American provincialism while enabling him to engage in a version of reconquista, a term that has recently been used ironically to describe Latin Americans taking advantage of the weakened European economy to buy property there and in some cases to relocate. The once-stark distinctions between First and Third World are more permeable now, with economic collapse threatening nations associated with empires of the classical and colonial eras, such as England, Spain, Italy, and Greece. European Romanticism idealizes Native American archetypes, yet enables more visibility for an Indian artist than the willful erasure of Native peoples in the United States will permit. The result is that Durham gets more exposure and support for his work on the continent, if not any less pigeonholing of his practice. The disintegration of Europe’s cultural and economic dominance is rich subject matter for Durham, whose signature re-mixing of salvaged materials is ideally suited to questioning the hierarchies of European material and formal aesthetics. His time in Europe has prompted the artist to investigate the properties of monumental architecture from his customary trickster’s perch.

Durham deconstructs urbanism by deflating its self-regard. “Maybe this piece is not finished well,” he writes in Suggested Proposal for a New Architecture No 3 (2003), an assemblage of found wood carved with laurels and a pitted sedimentary rock. “Should there be another stone?” Durham understands architecture from both the aesthetic and the labor positions. Whether dropping a rock onto a car in Still Life with Stone and Car (2004) or smashing a urinal with a large stone in Homage to David Hammons (1997), he recognizes the fuzzy distinction between the street as a space of constructed national identity and leisure, and as a site of potential armed resistance. Inside and outside, public and private, institution and town square are flexible categories, and a brick can be a tool or a weapon. Here Durham, ever the iconoclast, nonetheless wears European influences, such as the French Situationist Guy Debord, on his sleeve.

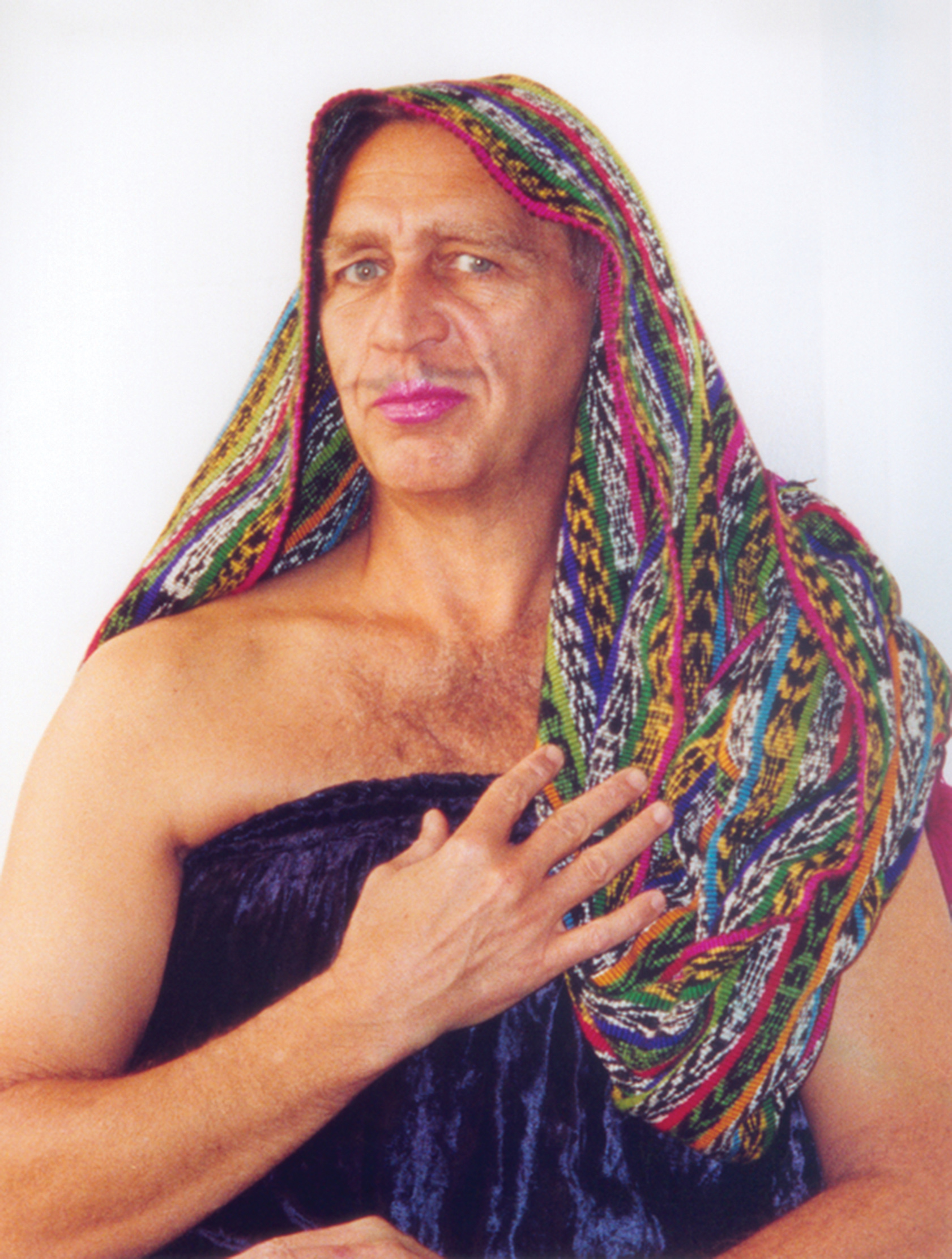

The Western art historical canon comes into play in tongue-in-cheek homages to Brancusi and Magritte, interspersed with Beuysian acts of artistic self-invention. These strains have always been in the work, as indicated by Self-portrait Pretending to be Rosa Levy (1994), an early photographic riff on Man Ray’s photograph, Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy (1920–21). The urinal of Homage to David Hammons is another obvious reference. In Europe, though, Durham is wrestling with his own passage into history. In 1948 (2012), the artist looks at newspaper fragments and ephemera to consider the confluence of global historic events that shaped his world view at the age of eight. These materials are assembled into works on paper that chronicle social and political upheavals, including the exodus of Palestinians out of lands now designated for the Jewish state of Israel, the forming of the Hell’s Angels in the United States, and the assassination of Mohandas Gandhi in India, from the artist’s individual viewpoint as one who has lived long enough to see current events pass into the canon of history.

Jimmie Durham, Self-Portrait Pretending to be Rosa Levy, 1994. Color photograph, 32 × 24 in. Collection of fluid archives, Karlsruhe. Courtesy of ZKM I Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe.

Though Joseph Beuys famously likened socially engaged artistic practice to shamanism, Durham is not an artist who can be lauded or followed in the manner of a religious leader. He is unwilling to seduce the viewer with false promises of redemption. All of Durham’s work, however mundane or even abject, is anchored in material and historical research. A reality of what is, not only an idea of what could be, forms the backbone of his practice. If Durham is a shaman, it is not because he operates on a spiritual plane, but instead because our collective disengagement with the technologies that enable culture, philosophy, and art has rendered us so ignorant of them that we mistake his extraordinary skill for magic.

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and educator based in Los Angeles. She is Artistic Director at 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica, California, and Senior Lecturer at Otis College of Art and Design. Her research combines media studies, theory of globalization, and critical race discourse with international art history from the early modern to the present.