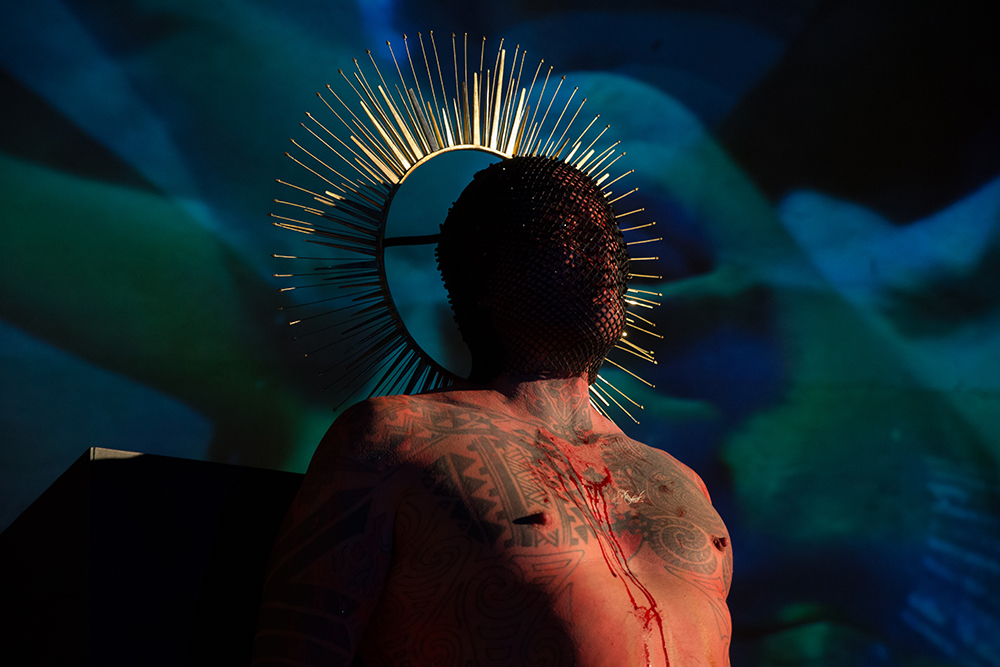

Ron Athey, Acephalous Monster, 2021. Performance at REDCAT, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist.

The survey exhibition Queer Communion: Ron Athey, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (ICA LA), paid tribute to the artist’s longtime engagement with queer subcultural communities and collective gestures of survival. In conjunction with the exhibition, Athey performed the newest iteration of Ron Athey: Acephalous Monster at REDCAT, in downtown Los Angeles.1 The performance is named in reference to the headless social body (acéphale) in the anti-fascist eroticism of Georges Bataille. The performance’s overarching emphasis on ritualism, rebirth, and the violence of homogeneity activated materials and objects featured within the exhibition. Athey’s incorporation of many of the performance props and regalia from Queer Communion within Acephalous Monster provided context for the structural shifts and formal organization of the performance while loosely paralleling the conceptual organization of the exhibition. Because Athey’s body-based practice is active and ongoing, this archival exhibition is best understood when read through the artist’s performance of Acephalous Monster.

The exhibition was curated by art historian Amelia Jones and premiered at Participant Inc., in New York (February 14–April 4, 2021). Queer Communion’s iteration at the ICA LA was organized in the same format as its earlier presentation. Five distinct thematic arenas encompassed a loose chronological purview of early artworks, documentation, and ephemera from the artist’s earliest forays through present-day works and collaborations. The installations at the two venues opened and ended with many of the same materials and artworks, however, each presentation was made distinct through its accompanying performance. At Participant Inc., this included Performance at Participant in 3 Acts, in which Athey performed alongside Hermes Pittakos, Mecca, and Elliot Reed. This performance took place on February 16, 2021, and included an opening solo word action by Reed, a reimagining of sound poet Brion Gysin’s Pistol Poem (which Gysin recorded for the BBC in 1960); and a reprise of Athey’s Printing Press (1994).2Both exhibitions and their related performances formalized a concept of the fungible body, specifically Athey’s body. Drawing on theorizations of the fungible body politic as symbolic for transition, boundarylessness, and sacrifice—which Athey’s performances make explicit through his invitation of physical, visual, and conceptual exchange with collaborators, audience members, and chosen kin—I posit the fungibility of Athey’s practice as the transformational eucharistic self-sacrifice implied in Queer Communion.

Fungibility operates here as a descriptive term for interchangeability, rendering the body into an abstract and exchangeable form. The idea of human fungibility and its historical parameters has been explored most vigorously in Afro-pessimist discourses that seek to reconceive the racialized body as commodity.3 I seek to expand on these discourses and consider its application to bodies rendered socially abject, that is, queer bodies, HIV-positive bodies, poor bodies, and beyond. Contrary to the term’s conceptualization in Afropessimism, Athey’s fungibility is largely conceptualized outside of racialization. The role of whiteness as a seemingly neutral, or empty, racial signifier consequently permits Athey to situate his body as a dis/embodied vessel capable of assuming others’ desires and values.4 This is not to say that Athey’s work is strictly hinged on the figure of the white queer body but rather to contextualize it in respect to its socio-historical positions.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, June 19–September 5, 2021. Courtesy of ICA LA. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The figure of whiteness is similarly highlighted throughout the exhibition and catalog, including in the artist’s personal accounts of his upbringing in extreme Pentecostalism and his personal essay “Flirting with the Far Right.”5 The essay offers an intimate reflection on the swastika tattoo that adorned the back of Athey’s neck for nearly fifteen years before he had it covered over. Athey’s engagement with body modifications and the subcultural communities they herald can be understood as fungible lapses in time rather than as historical reference points. In the schema of Queer Communion, this figured as a crucial conceptual figure, given the exhibition’s shift away from a historical survey. In tattooing, the skin is purposefully wounded and filled with ink, thus the swastika continues to be a part of Athey. The artist’s recurrent use of the martyr figure and self-sacrifice in relation to Bataille then seems to cue a personal reckoning with fascism. Athey became disillusioned with far-right aesthetics and its historical and contemporary significance. This is rendered explicit in the broader scope of Athey’s practice, which has sought to expose the efficiency with which bodies have been disciplined by heterosexist, patriarchal, and neo-fascist political fervor. Athey describes his initial interest in LA skinheads and far-right aesthetics as being specifically invested in the intersections between hypermasculinity and homoeroticism. This period, and the display of materials related to it within the exhibition, however, also posits the mutability of whiteness within his work and personal life. Here, the white queer male body is illustrated through wavering and messy situations within a variety of queer and queer of color communities.

Athey would later come to parody this figure of the impenetrable white body in Solar Anus (1998), named after the Bataille essay of the same name. The performance featured a dildo attached to a high heel with which Athey self-penetrated. Within the performance, penetration is framed as a way to explore, to quote Bataille, the “labyrinths of the physical body itself, down into the sacred precincts of cruelty, sex, and violence.”6 Similar to Bataille’s sentiments concerning the futility of personal transcendence, Athey’s own heel situates him as a kind of ouroboros, eating (or in this case, self-penetrating) his own tail.7 Unlike Bataille, however, Athey alters the conceptions of sacrifice found within the essay to instead reimagine the ritualized opening of the body as a gesture of vulnerable excess. In Athey’s Solar Anus, the figure of the sun as a source of both life and death becomes analogous with the abject queer body. The work’s reliance on the queer body as socially fungible further situates the work as both an impersonal and exchangeable encounter wherein the body is framed foremost as a medium. Given Bataille’s assertion that sovereignty is only achievable through the obliteration of the conscious mind—the headless (acephalous) being—the anus is presented as a reconceived opening to the body and subject. Here, the viewer is invited to enter through the cavity of Athey’s headless metaphoric space, which, though devoid of a mouth, is prominently sprawled open for visitors to insert themselves inside. Athey’s conceptualization of the acéphale echoes Bataille’s proposition that the acephalous man could act as a rejoinder to fascist authoritarianism. Aside from Bataille’s anti-fascist imperatives, Athey’s contrasting figures of whiteness are rendered vulnerable under the looming threat of salvation—beheading. Exemplifying the mystical ontologies and graphic excess of the erotic specific to Bataille’s work, Acephalous Monster and Queer Communion respectively countered the fascist body with the fungible and fluid body.8

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, June 19–September 5, 2021. Courtesy of ICA LA. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The figuration of anal penetration recurs throughout the exhibition and the accompanying performance, and the asshole is figured here as an omnipresent physical characteristic and realm for politically subversive potential. (To quote Mario Mieli, “What in homosexuality that particularly horrifies homo normalis, that cop of the hetero-capitalist system, is being fucked in the arse.”9) Beyond the theoretical conceptualization of anality, works including Solar Anus and a Rod ’n’ Bob sketch from the early 1990s (an artifact from the Rod and Bob: A Post AIDS Boy-Boy Show performance in 1995) visualize the central role of anality within the scope of the exhibition, accompanying screenings, and the performance of Acephalous Monster. Each of these works illustrates a Bataillean preoccupation with the anus as a fluid site for excremental and erotic exchange untethered by the regimens of heterosexual reproduction. Athey’s recurring motif of the glory hole further antagonizes the rigidity of heteropatriarchal sex roles and its parallels with fascist bodies. The glory hole rendered on either side of the Enchanted Womb, Ark of the Covenant (2021), a horned sculpture inspired by the Cretan conception mythology of the Minotaur and created for Athey’s film Pasiphäe, Witch Queen of Crete: A Glory Hole Origin Story (2021), personifies Athey’s ongoing interest in the polemics of the penetrative body within far-right discourses.

Athey’s ongoing theme of the acephalous subject recurred throughout the exhibition in headless mannequins adorned with leather (cured skin), costumes, and performance regalia. The first mannequin, placed near the entrance, wore a bright red dress from Joyce (2002). The performance, named after the artist’s mother, perverts the matriarchal figure through taboo, violence, and hyper-sexualized familial acts. Another was dressed in the billowing ochre cape gifted to Athey by the late performance artist and club kid Leigh Bowery. Bowery, a kindred spirit, similarly exposed himself to vulnerability within his performance, which often comprised physical injuries as a sociopolitical gesture. Before Bowery succumbed to AIDS at age 33, he produced a body of work with a far-reaching scope. Bowery’s cloak was featured in the “The Holy Eunuch” section of Athey’s Incorruptible Flesh (A Work in Progress) performance, staged in 1996. The headless subject is similarly prodigal within Acephalous Monster, for example in an orgiastic video involving phallic totems, which were also on view at the ICA LA.

Athey expanded the Los Angeles iteration of Acephalous Monster to five acts and introduced a queer revision of historical and mythological encounters. Broadly organized around considerations of erotic transcendence, fetishism, and power as analogized by Bataille’s headless acéphale, Acephalous Monster cued the foundational significance of bodily interchanges and the discourses that continue to push back against it.10 Acephalous Monster greeted audience members with a projection of Bataille’s foreword to My Mother (1964), which comprised a brief excerpt detailing a young man’s sexual initiation by his mother. This figure of the incestuous mother was mirrored in a number of materials on display in Queer Communion, including Joyce’s red dress. Athey’s ongoing investment in inverting normative conceptions of the mother as a stable, cis-gendered caregiver reflects not only his personal experiences, about which he has written extensively, but also his conceptual interest in the subversive potential of maternal archetypes.11 Within Athey’s performance and installation, the mother exists outside of a nuclear patriarchal relation and is transfigured into an erotic and sometimes menacing figure. Athey has discussed his own dysfunctional childhood experiences at length in a number of autobiographical writings that are included within the substantial Queer Communion exhibition catalog. Collectively, these gestures signal the pertinence of (re)creation, the exchanges that give rise to it, and more precisely, the role of the fungible, multilayered, and porous body as a liberatory site. For Athey, re-grounding a normative origin point (motherly birth) is an opportunity to reimagine alternative entry points into subjecthood and becoming.

Experimental vocalist Carmina Escobar’s overture for Acephalous Monster was accompanied by the music of the Los Angeles-based performance group Opera Povera, producing a haunting introduction to the performance using glossolalia, or ritualized tongues. The rich homorhythm of Opera Povera undergirded Escobar’s raucous and at times piercing vocalizations. The performance was conducted with a single spotlight focused on Escobar; the accompanying musical ensemble was visible solely through indirect light in an otherwise pitch-black theater.

Ron Athey, Acephalous Monster, 2018. Performance at Performance Space New York. Courtesy of the artist.

The overture was followed by “Act 1: Pistol Poem,” based on Gysin’s “Pistol Poem,” which was conceived as a sound assemblage that employed a “cut-up” technique to combine different sound clips. Gysin’s original featured recordings of a gun being shot at different distances that were spliced together using a number sequence that Gysin developed, based on the permutation principle.12 Athey’s interpretation of Gysin’s poem featured the artist in choreographed synchronicity with performance artist Hermes Pittakos and Escobar atop a white, five-by-five-foot grid. Athey, Pittakos, and Escobar each donned formal attire while marching atop the grid guided by random permutations between one and five. Escobar, who was dressed in a tight pencil skirt and white blouse while Athey and Pittakos donned suits, walked up and down the grid. Occasionally, Escobar glared toward the theater’s seating, only to return to face Athey and Pittakos and intermittently fire a blank casing out of a small handgun. Athey’s reimagined “Pistol Poem” employed much of the same rigidity and violence personified within Gysin’s initial work while also enacting a gendered inversion by specifically designating the gun to Escobar.

“Act 2: Dionsysus vs. The Crucified One” visualized a backwards “fall” drawing on the mythologies of Dionysus. This segment of the performance featured Athey reading part of Bataille’s lecture “The Madness of Nietzsche (The Horse of Turin),” in which Bataille asserts that Friedrich Nietzsche had saved his life by turning him against organized religion.13 Athey’s reading of the text was accompanied by a text projection on a large screen that slowly transitioned into a graphic video, Conception of the Minotaur (2019), which depicted the conception of the Minotaur, who was the offspring of King Minos’s wife, Queen Pasiphae, and Poseidon’s great bull from the sea. Using the Dionysian mysticism conceived by Bataille within his figuration of the post-Renaissance figure, Athey here renders the Gnostic fall as a descent from Christianity.14 In the video, Pasiphae, played by the performer Moe, is on all fours and vigorously penetrated by an ebony cane. The video’s erotic visualization of the Minotaur’s creation in a bestial exchange symbolized transgression and rebirth at the hands of a violent society. Act 2 thus illustrates a Bataillean concept of the creation, destruction, and tentative re-emergence of mortality.15

Ron Athey, Acephalous Monster, 2021. Performance at REDCAT, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist.

The third act, subtitled “To Celebrate the Beheading of Louis XVI,” opened with Opera Povera’s brief performance of compositions set to excerpts from Bataille’s The Sacred Conspiracy: The Internal Papers of the Secret Society of Acéphale and Lectures to the College of Sociology (1936). Bataille’s collection of writings and meditations explores the role of the sacred in society. In the performance, Athey was heavily powdered and adorned with a white wig parted down the middle (evoking Louis XVI and also the 1992 filmic adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula) and a billowing, open-front gray robe. Seated in front of a vanity, Athey vigorously powdered himself in anticipation of his execution. In the middle of the darkened theater, plumes of powder filled the stage, further exaggerating an already parodic gesture. Athey’s pending decapitation was underscored by the video The Executioner and the Labyrinth (2018), starring Divinity Fudge, clips of which played in the background. Fudge’s black-leather-clad figure loomed behind a writhing and erratic Athey. The figure of Louis XVI eventually moved behind a tall movable wall with a single hole, through which he placed his head. Facing the audience with cascading locks, the artist shouted, spat, and slurred his words; then his metaphoric beheading took place. The scene brought to mind parallels between eighteenth-century and contemporary political tyranny, and the flamboyant hubris (and demise) that so often accompanies it. The identity of the decapitated figure was rendered fungible such that the audience bore witness to both Athey’s and Louis XVI’s beheading. This transformation gestured to the malleability of historical figures, be they mythological or factual. The protrusion of Athey’s head through a black hole also formalized the anality of the performance and its variants of penetration.

With its theme of fungibility largely hinged on decapitation, the performance was structured as a headless and prominently anal figure. “Act 4: Apotheosis” revived (or rebirthed) AthAIDS epidemicey as the Minotaur. Here, Athey sat naked while bathing in a bright orange neon substance that coated the entirety of his body. The seemingly amniotic liquid symbolized Athey’s transition into a mythological being and cued a merger between the human and the divine. Adorning the bright red bull mask that was on display in Queer Communion, Athey appeared phantasmal as he writhed within the glowing liquid and a fabricated umbilical cord. This gesture recalled the Executioner and the Labyrinth video in act 3, visualizing the Cretan mythology of the labyrinth and the Minotaur born of the mother’s transgression (as seen in act 2). Beyond the fourth act’s direct invocation of labyrinthian models of rebirth and transformation, this action also spoke to Solar Anus, in which the anus is rendered as a heterogenous space (dark, excremental, pleasurable, and beyond the social). The cyclic and performative rebirth of the queer body within this action then seems to reify the minotaur’s creation as amorphous, taking place both apart from and through heterosexual bodily exchange.

Queer Communion: Ron Athey, installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, June 19–September 5, 2021. Courtesy of ICA LA. Photo: Jeff McLane.

The performance’s finale, “Act 5: Enter the Forest of Acéphale,” opened with the video Entering the Forest (2019), in which six wooden totems tipped with colorful phalluses, which are part of the Queer Communion exhibition, are put to use. In the video, the long phalluses are wielded from a distance into a reciprocal body by performers, including Pittakos, Fudge, Cassils, Latex Lucifer, Lauren Davis, Missy Munster, Yunuen Rhi, and Pony Lee. The group swarms around a single crawling and seemingly disoriented figure who rolls around and across the poles on the ground until eventually lying down to be penetrated. This staging visualized Athey’s concept of embodied exchange—from metaphorical bodies to explicit flesh. At the video’s conclusion, the dark stage was slowly relit, revealing a naked and cleansed Athey standing against the same moveable wall that earlier had served as a guillotine. In this scene, the artist remained still while Pittakos cut into his chest and intermittently pressed gauze against the wounds. Athey wore a face cage by House of Malakai that was crowned by a sunburst-inspired headpiece, which imparted a Biblical sensibility to the scene. The carving action demarcated Athey’s ongoing investment in ritualized rebirth, religious purification, and erotic porosity. The accompanying video, informally titled “Recorded Text and Projected Word Virus: Cut-Up of Genesis P-Orridge’s Esoterrorist” (which included visuals and a recorded narrative text by Genesis P-Orridge) posited the body as a mutable, historically porous, and speculative site. Videos of ritualized piercing and carving were also screened in tandem with Athey’s live carving. Contrary to the seeming violence of the interactions featured throughout the video works and live actions, many of these exchanges were resoundingly intimate and contained moments of great care and affection.16 The act culminated with Horns of Consecration, a live action with Athey and Pittakos wherein the former was revived as the human Acéphale. This performance featured Pittakos carving into Athey’s erect and static body over the top of Athey’s sacred heart tattoos (which the artist credits as being done by the artist Bob Roberts in Los Angeles in 1982). The carving delineated two semi-abstract horns with a floating sphere between them. Following the cutting, Pittakos pressed white cloth sheets onto Athey’s freshly wounded chest, in a reference to Athey’s earlier work Human Printing Press (1994) from the performance 4 Scenes in a Harsh Life.

Both Acephalous Monster and Queer Communion opened and closed with works that illustrate matriarchal figures, transformation, and the communal—or fungible—body. Queer Communion formalized the figure of the matriarch and Athey’s revised conception of gendered human origin via the deviant mother—a violent and queered mother figure—in the four-channel performance documentation of Joyce. This experimental theater work used a combination of live performance and found and staged imagery to compose a rapidly shifting mother and daughter incest dynamic. The relationship, fraught with schizophrenia and dissociation, provided a largely allegorical account of Athey’s own familial dynamics. Each vignette within the work accounted for formative moments throughout the artist’s life, including self-harm and the sexual abuse of his aunt, which was represented through the douching and fisting scene of “Vena Mae.”

The intertwined relationship between Athey’s professional practice and personal life is illustrated throughout the exhibition. Candid photographs and letters in the section titled “Music/Clubs” document the time in Athey’s youth when he was a part of the homeless punk scene. A blown-up photograph near the beginning of the exhibition features a go-go dancing Athey wearing little more than a metal studded codpiece. Taken around 1990, by the artist Sheree Rose, the photograph captures Athey with his arms flung over his head and a euphoric smile across his face. Athey was a regular at the queer-inclusive Club Fuck! In Los Angeles, and the photograph celebrates the centrality of such alternative queer venues within his life. Subcultural and queer networks are paramount for many minoritarian communities who have been and continue to be marginalized by the crushing weight of US hetero hegemony. HIV-positive persons, including Athey, have witnessed many of the spaces and support systems crucial to their survival being compromised. Glib assaults on socially exiled persons and the spread of AIDS-phobic misinformation were well documented within the exhibition, including the views espoused by the sexist and self-proclaimed bigot, late North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, who led an outcry over the funding Athey received from a National Endowment for the Arts grant for a performance in 1994.17

Many of the performers in Athey’s videos and performances are close friends and like-minded artists whose practices explore parallel concerns. These collaborations bring layers of context to the work, including sound, racial and gender identity, and music. The artist’s early club and musical engagements include his work with the experimental industrial and performance art group Premature Ejaculation, which Athey formed with the late Rozz Williams in 1981. (Williams went on to achieve fame with his goth rock group Christian Death.) The exhibition includes archival photographs of Athey and Williams performing for the camera in Ewa Wojciak’s LA publication NO Mag Issue 3 (1982), and stained letters from Williams attest to the influence of these networks on Athey’s practice. Ephemera on display from Athey’s performance Trojan Whore (1995–98/2007), a work that grew out of his friendship with Bowery, includes performance stills, a Trojan Whore rubber mouth sex toy, and a paper dress printed with an image of Athey as the Trojan Whore, from Travis Hutchinson’s book Worship: New York Underground 1994.

The recurrent theme of the communal body was manifested in the exhibition’s culminating work, Enchanted Womb, Ark of the Covenant, a horned and viscera- lined set piece replete with dual glory holes. The wooden structure was devised for Pasiphäe, Witch Queen of Crete: A Glory Hole Origin Story, which was filmed at the Philosophical Research Society in Los Angeles. The film visualizes Athey’s conception of the Minotaur’s origins, and the horned structure is used as a vessel for copulation. Adorned with steer horns and a chained support strap, the sculpture alludes to the simultaneous presence and absence of a body by highlighting its interiors and dual entry points (or exits).18 The object’s use as a container for the turbulent and violent sex act inflicted on Queen Pasiphae connects the work to the video Conception of the Minotaur, in which one of Athey’s wooden totems stands in for the phallus of Poseidon’s white bull. Scenes depicting amniotic fluids and fetal forms that are featured post-penetration within Pasiphäe, Witch Queen of Crete and during Acephalous Monster emphasize the cyclicality of birth/origin, life/ transformation, and death/reintegration, which is represented through contrasting visual cues, such as the use of blood as a signifier for birth and death.

Ron Athey, Enchanted Womb, Ark of the Covenant (2021). Plywood, steel chain, leather straps, steer horns, sawhorses, aluminum rods, pantyhose, fiber stuffing with pigment, latex, and silicone treatment. Installation view, Queer Communion: Ron Athey, Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, June 19–September 5, 2021. Courtesy of ICA LA. Photo: Jeff McLane.

In positing physical fungibility as a realm for radical resistance, the myriad histories of the communal body and its continuously tenuous position in Western contexts must be taken into account. Within gay liberatory movements specifically, collective attempts to reimagine the body as a porous and open site are fraught with the devastating lineage of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. How might one reconceive of the body, specifically the queer male body, as a site for porous physical exchange without romanticizing or feigning ignorance of the perils that continue to surround it? The literal and metaphoric bodies that comprise the exhibition and accompanying performance explore these questions. Subtle incorporations of Athey’s conceptual body within the exhibition include the Human Immunodeficiency (HIV) model prop and Foot Washing Set w/ Blonde Hair Towel (1996). Athey, who has been HIV positive since the mid-1980s, installed the HIV model, which he stole from a doctor’s office around 1990, on a stark white shelf, rendering the cell as if floating. Foot Washing Set, an ode to the Catholic matriarch Mary Magdalene and a nod to Christian foot washing practices (see Luke 7:44), extended the body through its materiality—a disembodied blonde wig turned towel and a bloodstained brush. These gestures turned the space itself into another type of body, which viewers were not only engaged with but also actively moving inside of—penetrating. The exhibition’s culminating glory-hole-laden set piece from Pasiphäe, meanwhile, reified the type of penetration that viewers were actively participating in, that is, anal, as a shared space that typifies both an opening (the asshole) and ending (shit). Here, the artist’s interest in the polymorphous queer body is rendered prodigal through the excess of sweat, blood, and sores that stain the expanse of his heterogenous work.

Across the breadth of Athey’s work, and more specifically in Queer Communion and Acephalous Monster, the body can be understood as literal, discursive, and metaphoric. The presence of the body—always material and at times conceptual—is figured across a variety of forms, including vessels, orifices, and objects, as well as through actions that signal its presence. At times, this metaphorical body is rendered explicit through the incorporation of facsimiles or artworks that feature bodily fluids from Athey himself. The concepts driving Acephalous Monster and reflected in the assemblage of materials in Queer Communion present this fungible and queer body as a headless and forwardbending invitation. The body here enacts an invitation to explore the complicated legacies of queer identity, autonomy, and methods of creative resistance. The exhibition and adjoining performance both exemplify the prodigies of sacrifice that continue to substantiate Athey’s work and elicit the vitality of and necessity for kinship and communion. Though Athey’s exhibition, performance, and body all function as metaphors for the interplay of ideas strewn throughout, each one also considers the viewer’s relationship to itself. That is to say, although Athey’s corporeal and metaphoric form provides the theoretical flesh of Queer Communion and Acephalous Monster, the viewer is also reminded of the ways in which people become visible as others and the weight of our respective (and shared) histories. With both the performance and exhibition replete with bodily fluids, personal documents, and candid stills, this relationship between the viewer and Athey becomes an intimate one that transforms into the penetrated and the prone. Here, Athey’s figure is rendered vulnerable, porous, and replete with all of the fluids, shit, and detritus that comprises and transforms living bodies.

April Baca is a professor of art history at California State University, San Bernardino, whose research focuses on feminist visual media and queer Latinx identity in contemporary art. Xe has written extensively for scholarly journals and publications, including The Journal of Curatorial Studies and Art Journal and is currently pursuing a PhD in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.