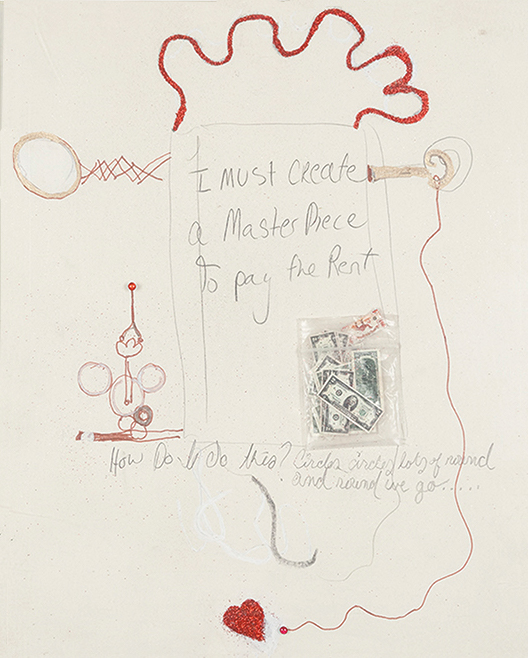

Julie Becker, watering (detail), 2015. Mixed media, 10 3⁄4 × 8 3/8 × 1 1⁄2 in. each. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

Originating at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London and traveling to MoMA PS1, Julie Becker’s recent exhibition offered a roughly chronological journey through the artist’s interdisciplinary and multidimensional artworks, which include photography, drawing, sculpture, installation, film, and force fields. The title—I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent—is lifted from Becker’s triptych of drawings titled watering (2015), which she made the year before her suicide. The statement is all the more heightened today, when paying rent and bills is untenable for most, earning money is exhausting and precarious, and the idea of saving it is a cruel joke. At its core, Becker’s work opens up a space of impossibility, pointing toward countless imagined realms—parallel yet interconnecting—and inviting you to enter into a golden sense of belief. Born in 1972, Becker grew up in Los Angeles, frequently moving with her mother between single-room apartments and hotels. In 1993, while studying north of the city at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), Becker began making her series of photographs of Interior Corners, which the PS1 exhibition takes as its starting point. These images are simple in composition, peering into brightly lit corners. Two walls covered in smooth wallpaper or wood paneling meet a carpeted floor, which seems somehow both aged and crisp. In most, the space where they connect is separated by a strip of skirting.

Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, installation view, MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

In some images, the strip is a saturated black, giving the optical effect of a hovering false wall with a dark gap below that seeps into an unknown space. Sometimes the glossy wall covering reflects floating orbs of light. Although filled with detail, the corners are both physically empty and haunted by something. In this sense, they appear to be both concave and convex, much like the visual effect of their three conjoined planes. There must be a person just outside of the frame and occupants on the other side of these walls. The images resemble dreams or memories; the feeling is strong but the edges of things are not so clear. A corner is a lonely place, even more so under Becker’s theatrical lighting. Her corners remind me of the impressions of each new home I moved into as an only child—of being kept inside and staring blankly at the details in ceilings and corners for stretches of time. Alone in your room, blank moments face you over and over. Then, imagination attempting to cure loneliness, you invent your own worlds.

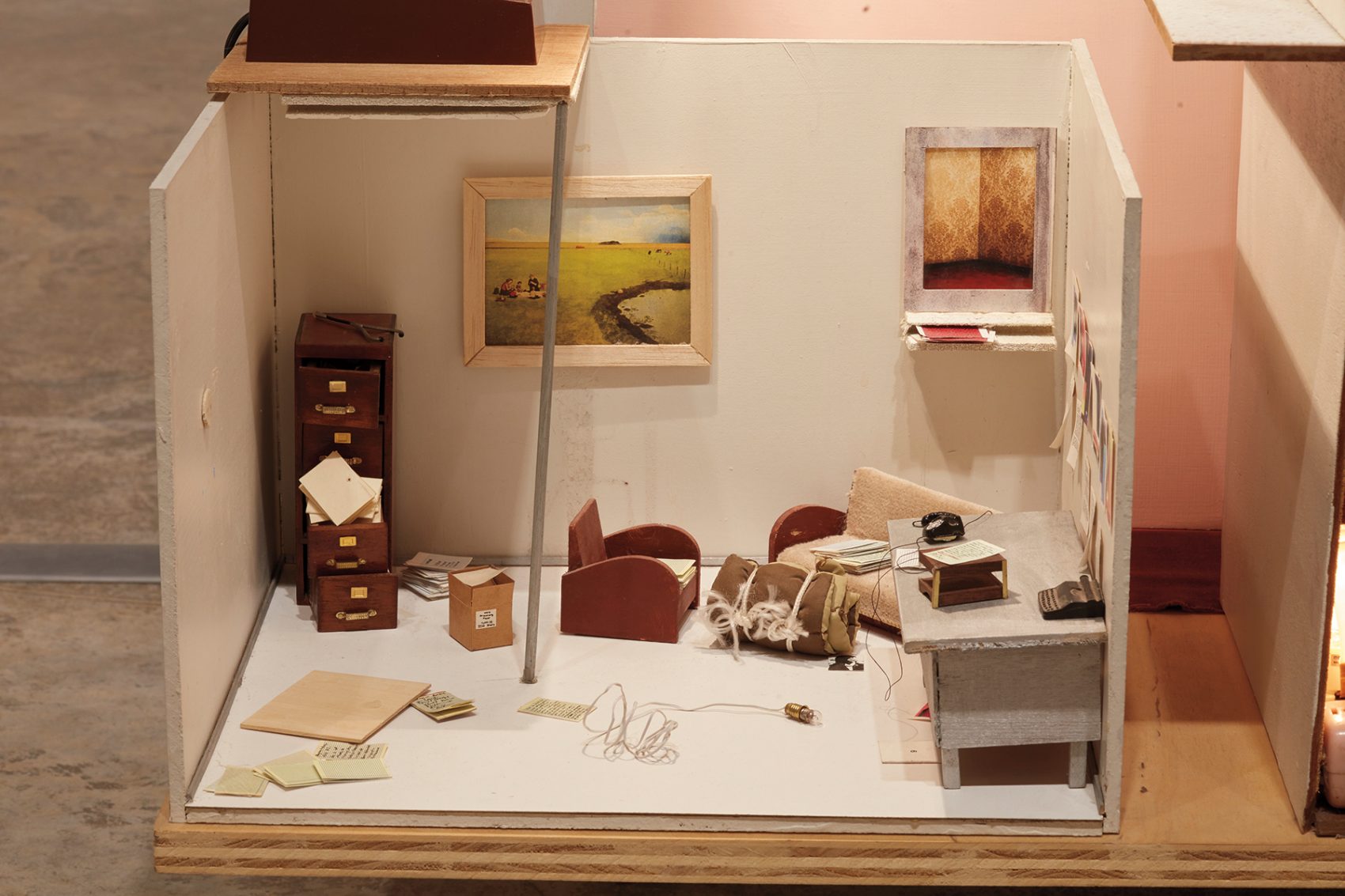

Becker’s Interior Corners are accompanied at PS1 by Poster Size Copy Machine (1996), a dollhouse-like model of interconnecting rooms lit by a series of regular-sized desk lamps. Looking in, the corners from the photographs materialize at a much smaller scale. Becker had photographed both actual-size and miniature corners, printing them to a consistent poster-sized format so as to confuse an interpretation of their scale.1 Some of these rooms could have served as models for the photographs, were the sculpture not made three years too late. Tiny belongings (a rat trap, a bench, a sleeping bag) sparsely populate the model as if somebody just vacated. Shrunken versions of the photographs are taped to the walls, and scattered piles of miniaturized notes (both typed and handwritten) describe various absent people. Some of these are almost too small to read. (During one visit, a gallery attendant offered me a small magnifying glass on the condition that I wouldn’t drop it into the work.) A typed description of Resident #12 reads: “They are often overworked, and as a result may suffer from psychosomatic illness.” These notes seem to be the investigations of a psychologist and, in fact, upon my own further investigation, they turn out to be slightly altered versions of Myers-Briggs personality profiles. Resident #10: “But the whole chain of events presents a confusing and paradoxical picture to an outsider.” Looking into these rooms, as an invited viewer in a museum, you also become the unannounced voyeur-inspector of these notes and belongings.

Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, installation view, MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Becker deploys small models, elevations, and plans throughout her work. They are, by implication, always connected to something larger—human-scale—at least speculatively and potentially. Nearby, a series of drawings from 1994 also serves to introduce the exhibition. Plan of the Principle Story (study for installation) shows the façade of a populated hotel building, with plans of the ground and top floors placed at the bottom corners of the page. The windows are occupied by people (characters), except for one in the center of the top story, which remains empty. What seems to be a blank sign or projector screen—the same freestanding kind that physically appears in Becker’s later works—is placed in front of the hotel, although a block of drawn lines is missing. It’s as if these zones of detail simply could not be verified or found by Becker.

At PS1, all of these works precede an enclosed space, the exterior of which remains unfinished by sheetrock, its wall studs still visible from the outside. The interior contains Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, which Becker made from 1993 to 1996, the years between her Interior Corners and Poster Size Copy Machine. This project ambulates through loops in time, space, and narrative. Culminating in her final MFA show at CalArts, Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest was first exhibited in one large enclosed room that contained various spaces and imagined realities. She was invited to exhibit the installation again for the 1996 São Paulo Art Biennial, and with this institutional support Becker realized the installation within three separate but still altogether enclosed spaces: two full-scale tableaux were divided by a middle space that contained a series of refrigerator-box sculptures as well as two sprawling models. She realized the work again the following year at the Kunsthalle Zurich. The final time Becker herself installed Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest was at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 2003, after it had entered their collection.2 By this point, its three-room form was established, although each iteration saw gradual shifts in detail and internal activity.

Its presence in I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent marks the first time the installation has been realized without Becker’s oversight and since her death. Encountered here, the multilevel and maze-like Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest is difficult to describe without entering into obsessive detail. In the artist’s words: “Some people think my work is like a homemade CD-ROM because of its nonlinearity, with various entering and exiting points. I think this is pretty funny because we would not have invented ‘being everywhere instantly’ if our minds were not there already.”3 Becker took on her process of research in a most true and literal sense. Unlike the “research” process found in much contemporary art, the work here is imbued with the messy evidence of a very real searching the frustration and persistence. Notes are compiled upon notes and connections are placed inside of references. Becker sought to research the invisible presences that she heard, felt, and knew to exist, and to prompt in the viewer the same process. The result offers something that most often happens inside of a book: going deep into tunnels of description and location. Throughout Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, Becker draws out a complex map of people and spaces that were in some subtle way already connected in the world, across realities.

Entering the installation one person at a time, you find yourself in a tight space with a faux wooden floor, pale yellow walls, a red rug, a small sofa, and a desk, on which a name plate reads “Waiting Room.” A collection of other name plates congregates on the rug Concierge, Entertainment Agency, Real Estate Agent, Psychiatrist—evoking various potential spaces at once. Two of the labels remain blank, as if also waiting. Compelled to continue moving through the short hallway that leads out of the room, you become caught up in a drawing on the wall near the exit, which shows two more floor plans. The left plan shows the ground floor, with rooms labeled in an apparent merging of characters and locations from Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film The Shining (including Jack, Wendy, and their psychic son Danny, based on Stephen King’s 1977 novel of the same name) and New York’s iconic Plaza Hotel, the setting of Kay Thompson’s children’s book Eloise (1955). This floor also houses the eminent Los Angeles psychic Voxx, whose room is labeled “The Intuitive Approach.” On the right is a plan of the upper floor: “The Objective Attempt.” The drawings are directionally complex, addressing the room you stand in while you look into them and offering clues about the spaces waiting in the installation’s immediate future. One ground-floor room is shaded in with an arrow pointing to it: “You Are Here.” Another arrow directs movement into what must be the next space of the installation: “Storage.” At the lower corners of the page stand two unlabeled doorways, implying other entrances or exits that are rendered in three-quarter three-dimensional view, in contrast to the flatness of the plans. It’s hard to tell when or where“here” is (a hotel?), and the exit becomes the next entrance into something vast and unknown (storage?).

Julie Becker, Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, 1993–96. Mixed-media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Jocelyn Miller.

As Danny in The Shining tricycles through the Overlook Hotel’s patterned hallways, sudden flashes of psychic terror face the child.4 He is in the space as he sees it, and he is also momentarily visited and surrounded by the past—or the future? or an alternative historical dimension? Theories about what “The Shining” is abound. In Becker’s waiting room, and into the middle room, the map functions like a psychic flash. On the other side of the exit/entry, a gallery space laid out differently from the map’s foretelling holds two obsessively detailed architectural models of its two floors. The models hover about a foot off the ground on wheels (ready to move), and you’re now looking into what seems to be a hotel or apartment building. Becker uses desk lamps to illuminate the rooms, which contain detailed furnishings, some seemingly deserted and others strewn everywhere as if by a malevolent force. Each of these single occupancies belongs to an absent “resident.” Becker: “I didn’t want to call them resident but I have to call them something. They are the anonymous people who the researcher in the model is studying.”5 The waiting room appears in the model as well, and so a strange spatial loop occurs—another portal between dimensions. Like the unfilled gaps in Plan of the Principle Story (study for installation), certain parts of Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest remain unfilled. Becker renders the space of residence (including now the gallery itself) a blank zone—a fraught metaphysical space, invisibly charged with the psychical and energetic impressions of others who have passed through.6 She links the two: “You could say that this project presents an inner world turned inside out. Though I prefer to see it as a zone of energy—yes, that sounds nice.”7

Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, installation view, MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Early in Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, the implied researcher is Becker herself, and from within this position she begins to warp scale like a switch in the brain. Actual-size cigarette butts are left in ashtrays on some corners of the models, as well as scattered Goldfish snacks and magnifying glasses—the apparent remnants of Becker’s obsessive research process. But an eerie doubling occurs because they might just as well belong to her (also absent) researcher. And then, being now the onlooker studying these objects, the researcher becomes you. Yet none of these states mutually excludes the other: like the relationship between the plan and the room that follows it, multiple universes and presences exist at once, managing to be both parallel and interconnected. As Markus Müller put it in an early issue of Afterall, you are “looking at/observing something that was created to look at/ observe something and it [is] being presented in a situation that [is] used by someone to look at/observe . . .”8 It’s easy to imagine the absent residents moving about inside the models, in which case you are the one who is invisible—like a poltergeist, potentially able to reach in and move the furniture of the people you cannot see and who cannot see you. Becker’s work is more than maze-like; it extends past the dimensions of the map and then the literal gallery space into four, five, or possibly infinite directions and times. These spaces are both physical and metaphysical, and as a viewer you peer into while simultaneously becoming a part of the installation. You slip between realities, as Becker said: “a ghost moving through the walls.”9

Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, installation view, MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

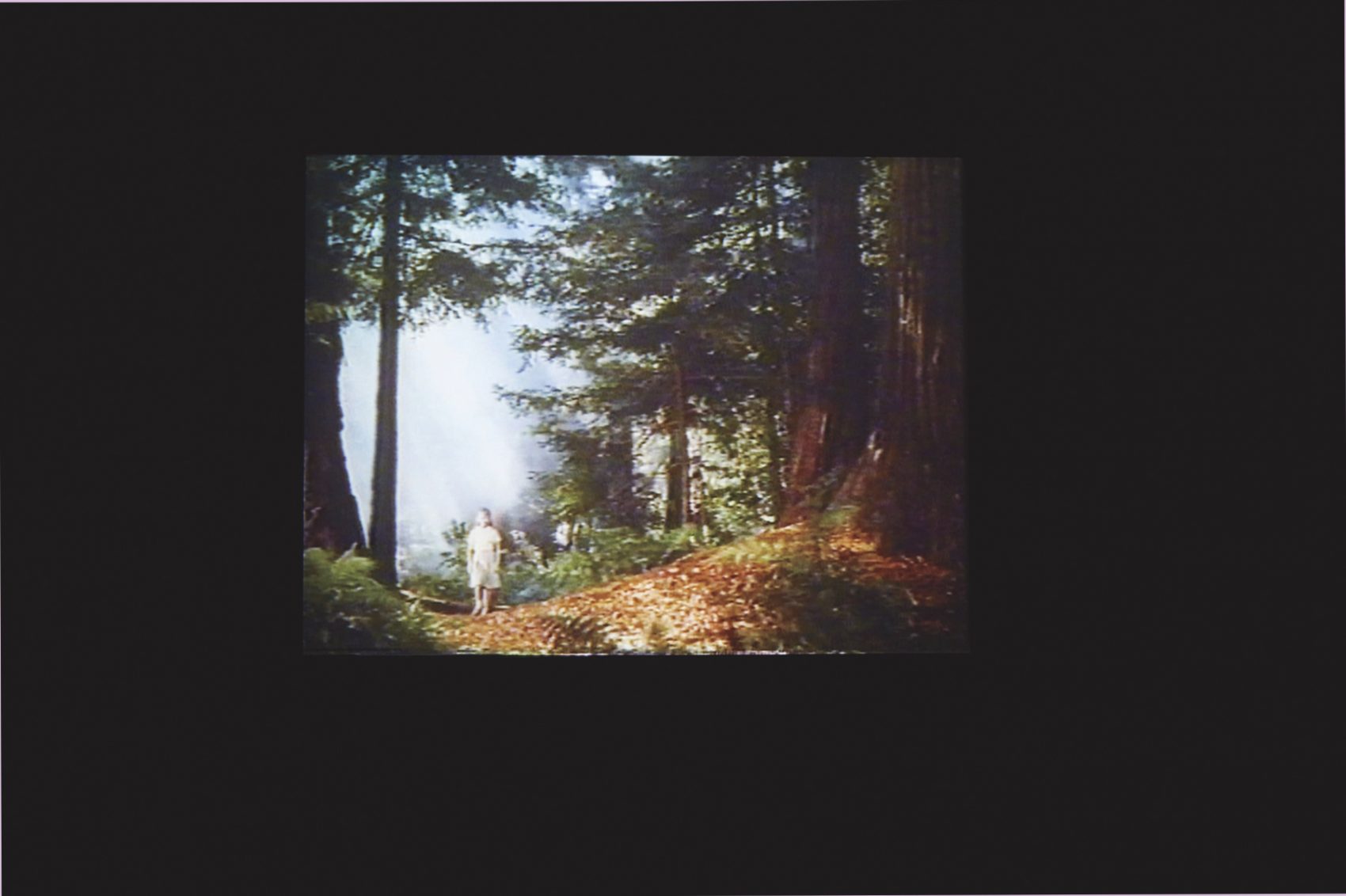

The third space of the installation is a narrow room running the length of the back wall, open on either end, a passage with no resolution. It contains a dense clutter of belongings, as if one room from the model were made life size; at the same time, it seems to be the researcher’s (and the artist’s) headquarters. Becker: “The back room is the brain center for the entire installation—it’s the workshop, storage room, the library. It isn’t separate.”10 This room contains pieces of evidence that might have further filled in certain blanks in the models and maps, had a different future arrived.11 In its earliest versions, this back room was “a hive of interactivity between the viewer, the installation’s environment, and the artist herself,” wherein one could sift through the room’s contents, including reading the handwritten diaries of Danny and Eloise, pausing and changing VHS tapes, making Xerox copies of things to take away, and so on.12 These possible interactions engaged the onlooker directly as part of ongoing research process. Despite the magnifying glasses scattered across the models and back room, viewers at PS1 could not touch the objects, and a journal is opened to one spread only (“Dear Diary, Do you mind if I write backwards from now on?”). This amplifies the absence of the once-present Becker-as-researcher, as well as the absence of her imagined researcher (the one who isn’t you), suffusing the installation with a sense of yearning and frustration. In her now infinite absence, Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest “allows viewers to experience themselves,” as Becker put it, “alternately as participants and observers” in a new way, as she always hoped it would.13 With the passing of time, the technological anachronism the of the installation’s objects begins to protrude, in itself multiplying the dream-like effects of absence and fiction as well. Exiting back through the waiting room, the second half of the exhibition lies “outside” the world of Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest. Becker’s Transformation and Seduction (1993/2000), a 4:36 minute video played on a loop, bridges the transition. In the video, a girl wanders through a deep forest of redwoods, her head tilted toward the shards of light streaming down. In the original (1993) version of this work, the girl searches and searches while a voice (Becker’s father) narrates slightly altered passages from Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Despair (1936). Becker lifted the imagery from the Disney film The Gnome-Mobile (1967), which was based on the 1936 novel The Gnomobile by Upton Sinclair, and montaged it with other mysterious footage, including a figure ascending dark hilltop structures, a hand surveying a map, and something rustling behind a hedge. Becker made the work in the year she began her MFA at CalArts. Placed at this point in the show, Transformation and Seduction doubles as a possible statement on her activity as both the creator of her works and a searching figure within them. The voiceover continues: “As if I were looking for and finding (and still doubting a little) proof that I was I, and that I was really in the forest, searching for one particular common girl, named ____________.”

Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, installation view, MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

The sequence cuts to black. “A transformation….” A woman runs down a green hill. When she reaches halfway between the edge of the frame and the bushes she darted from, a man rushes out after her. The chase scene loops over and over, producing a tumbling gravity effect as the narrator continues his monologue. Finally, the image cuts out as she reaches the middle ground, and her pursuer never appears again. In 2000, when Becker discovered that the original VHS tape had been lost, she fully recreated Transformation and Seduction. She rerecorded the voiceover, this time with a voice similar in timbre to her father’s. Again she sourced and montaged the visual sequence. Through this process, Transformation and Seduction becomes an early example of Becker’s use of multiple versions, a detail that offers its own internal map between her works and research. As Bruce Hainley notes, Nabokov’s Despair is itself “concerned with twins, doubles, mirrors, false cognates, deceit, dissociation, and death,” and the novel went through a series of versions.14 Becker’s “decision to remake the video formalizes and/or crystalizes her thinking, its marvelous hauntedness.”15 Across her works, Becker’s inclusion of various characters, usually children and women—Danny, Eloise, Shelley Duvall, Voxx, Judy Garland, the girl in the forest—functions as a vehicle through which she seems to subtly interlink her own personal identification with these figures across various narrative dimensions. These choices become clues in themselves, offering vehicles for believing and seeing beyond and between realities, pointing to her trust in her own extrasensory awareness as she finds connections—the artist calls this “karmic occurrence.”16 Becker’s choice of various doppelgängers aligns curiously with her repeated use of versions, including her semi-plagiarism of existing texts (Myers-Briggs types and Despair) and her recreation of her own works and the details within them (Transformation and Seduction, corners, maps, models).

In 1999, Becker made a different kind of version with the video Suburban Legend, adapting the stoner rumor that if one overlays Pink Floyd’s 1973 album Dark Side of the Moon onto the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz by syncing the album’s beginning with the MGM lion’s third roar, remarkable alignments will follow between image and music and, more deeply, between cultural contexts (of course, it helps to be high). Becker offered a long list of notes alongside the video, which was projected onto a freestanding screen, along with a wooden bench, headphones, and a remote control. She points out some of the possibly endless coincidences that occur in the video, and offers: “The first hour is far more interesting. So I suggest that if you happen upon this video towards the end of it, you should rewind it.” Mark von Schlegell wrote about Suburban Legend in terms of it entering into cultural phenomena: “At a certain moment in our nation’s history, mothers and fathers, in search of their new postmodern selves, began to leave large numbers of children in front of televisions, VCRs, stereo systems and comic books.”17 Viewed now, in the swirling deep end of the production of screen-based self-as-content, Suburban Legend proposes a lineage to the domains of popular conspiracy and mind-altered states that run through culture at a whole other register today.

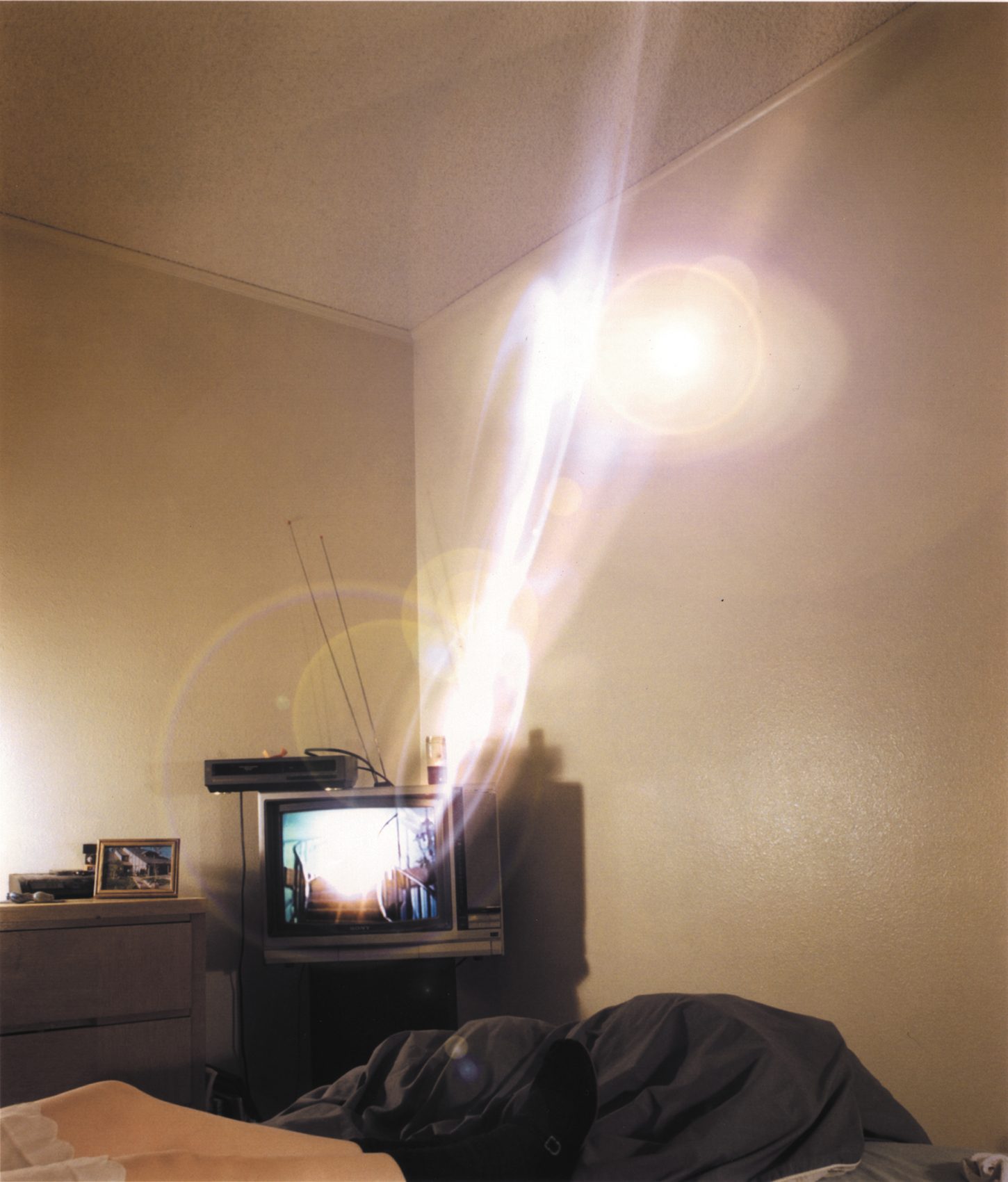

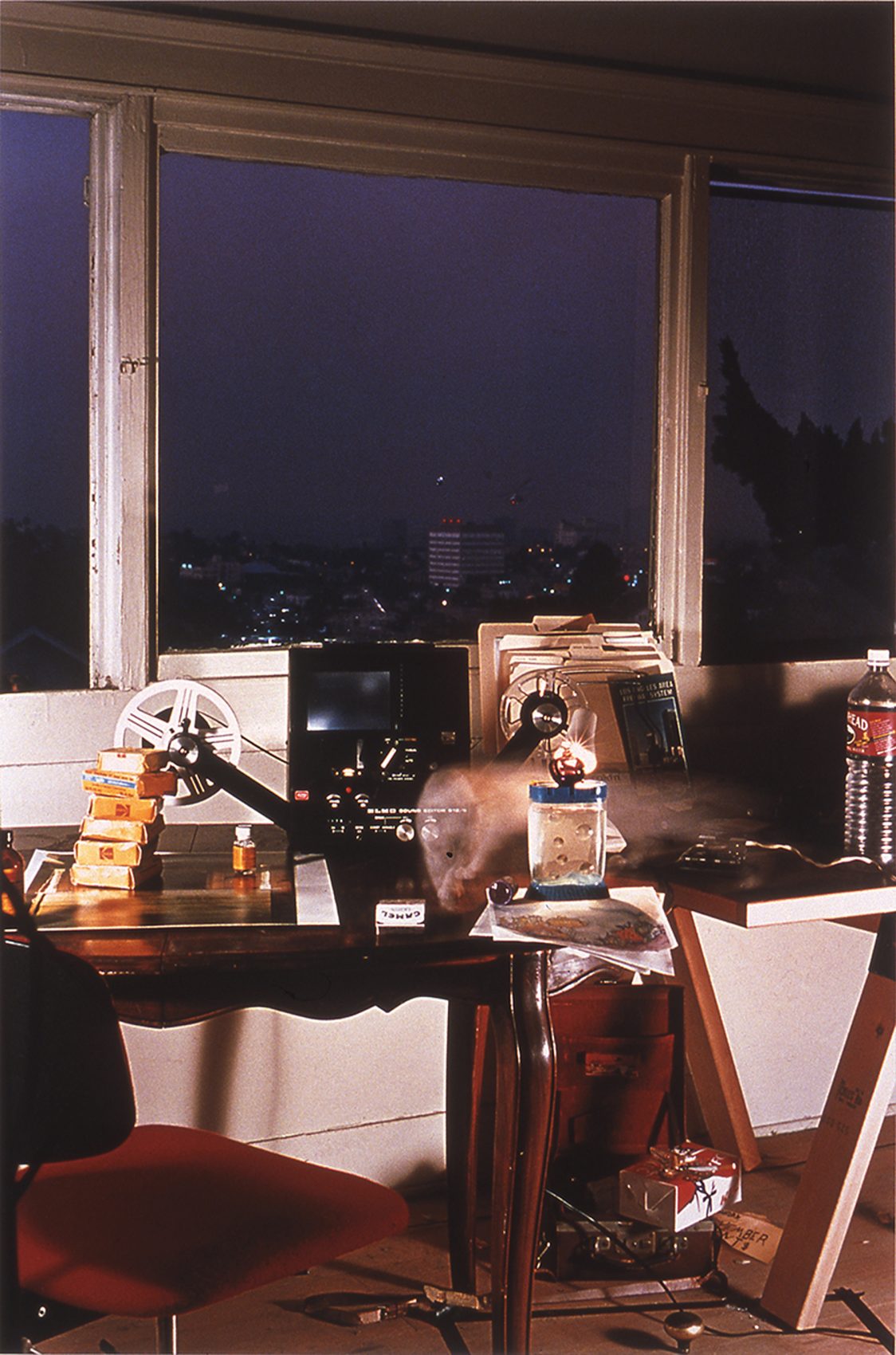

Continuing down the outside wall of Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest at PS1, the photograph Poltergeist (1999) shows a television in the corner of a messy bedroom. The TV plays the 1982 Spielberg movie of the same name, but the television image is mostly dissolved by a bright flash of light that reaches from screen to ceiling. How Becker managed to capture an image of a poltergeist is a mystery, but she renders the evidence of its existence audacious, right in front of us. Photographs like this one, printed at the same scale as her Interior Corners, recur as a thread through the exhibition. Around 1999, Becker moved out of her dingy single-room occupancy and into a larger apartment in Echo Park. The place was run-down and sinking slowly into the ground, not yet prime real estate, not even worth demolishing.18 The apartment was owned by the California Federal Bank, whose building was visible from the living room window. The bank gave Becker a rent break on the condition that she would clear out the belongings of the previous inhabitant: a stained-glass artist who had died from AIDS. His possessions were abandoned in the basement when nobody came to collect them after his death. As she sifted through his forgotten stuff, Becker entered deep into a search that became a new entry into her working process.19 “It’s like he mattered to no one. He was about as invisible as a person could be. I guess I wanted to bring him to life again and ask him some questions . . . as well as honor him just for making it through life as long as he did.”20

Julie Becker, Poltergeist, 1999. C-print mounted on aluminum, 50 × 46 in. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

The artist’s encounter with the apartment and its belongings could be understood as a karmic occurrence. What is a karmic occurrence? Perhaps this is the name for Becker’s mode of identification. A karmic occurrence could be a memory, a dream, a hallucination, or a light wave. It could involve psychically reaching into another realm and pulling something out.21 Moving into her new apartment as she moved on from her obsessive assembly of Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, Becker happened upon a reverse order of construction that she had not initiated herself.22 This period marked the beginning of her project Whole (1999– ), which would continue until her death, although the work’s date remains openended. At first, Whole was intended as an all-encompassing installation, driven by her awareness that “There’s always an attempt to be whole. Everyone in the universe has spent time trying to become whole through religious means, from sitting in a church to yoga to swimming, and everybody is trying to get more energy and become more whole.”23 This aspirational quest seems as intensified as it is reduced today, broadcast to individuals across subway and Instagram ads. Becker soon began to realize that her effort was impossible to achieve in practical terms, and she instead began to understand it more as a process of “an endless exposing of parts and not ever reaching a whole.”24 In the PS1 exhibition, Whole could be found in a grouping of distinctly titled works (drawings, photographs, and a video) and in a vitrine filled with Becker’s working notes, sketches, and reference photographs. A large series of drawings turned to a new manner of collage that made use of glitter and stickers and other shining, adhesive surfaces. These works comprise a mass of speculative structures and written text that seems to function as both Becker’s notes to self and as directions to the onlooker. Many would have been impractical to realize, but the drawings reflect her boundless perception and planning.

Whole was also a hole. Becker cut an opening in her living room floor to the basement, making the spaces one. Early in the project, she approached the basement as the “metaphysical-conceptual lab” and a rickety tiki bar structure that stood in the living room as “the underside of the belly of Whole”25—conducting a kind of spatial-conceptual inversion.26 Becker looked as deeply into as she stared out of the portal that was the apartment. She seemed obsessed with the CalFed building, as well as the helicopters that would land on its roof, inevitably causing her entire building to shake as their blades battered the air. CalFed was both her landlord and her view, as she documented in many photographs and drawings. She turned the building, covered in its own pattern of window portals, into a model. For her video Federal Building with Music (2002), she slowly lowered and lifted the miniature bank through the hole in the floor, intercutting that image with footage of the actual building from her window and from on top of its roof. Becker’s fixation on the bank connects to a pervasive sense of surveillance that runs through her work from the very beginning. The bank was inescapably contained in the very fabric of her home and took up the view of the outside, and the two observed each other. She was perpetually aware of others, and her awareness of their awareness of her is here amplified in the form of a corporate presence, linking her senses of presence with surveillance, making them one. Missing from the exhibition is the correspondence between Becker and the bank, which Whole also encompassed27—such as her letters about the apartment flooding.28

Julie Becker, Whole (Projector), 1999. C-print on aluminum, 50 3⁄4 × 33 3⁄4 in. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

One red note in the vitrine reads: “What comes out of a hole?” Below the question, a list: “Rainbows, Lava, Bubbles, Light.” As in her earliest projects, there was an outside to the lonely, rumbling inside. With the large sculpture 1910 West Sunset Blvd (2000), Becker replicated the sidewalk in front of the Brite Spot diner that (still) sits at the base of the bank building. In detailing this section—complete with yellow zoning paint, cracks filled with drying grass, and a drainage hole—Becker details the forces that continually act upon its supposedly solid terrain. The more positive energetic symbols of Becker’s hopes and intents seem to be the ones that are golden or glittering and hover in the sky—like the helicopters and UFOs in her works—or are barely visible in space, if at all.

Julie Becker, Golden Force Field (detail), 1999. Wood, concrete, wooden table, lamp, sheet of text, drawing with gold dust, color photograph, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

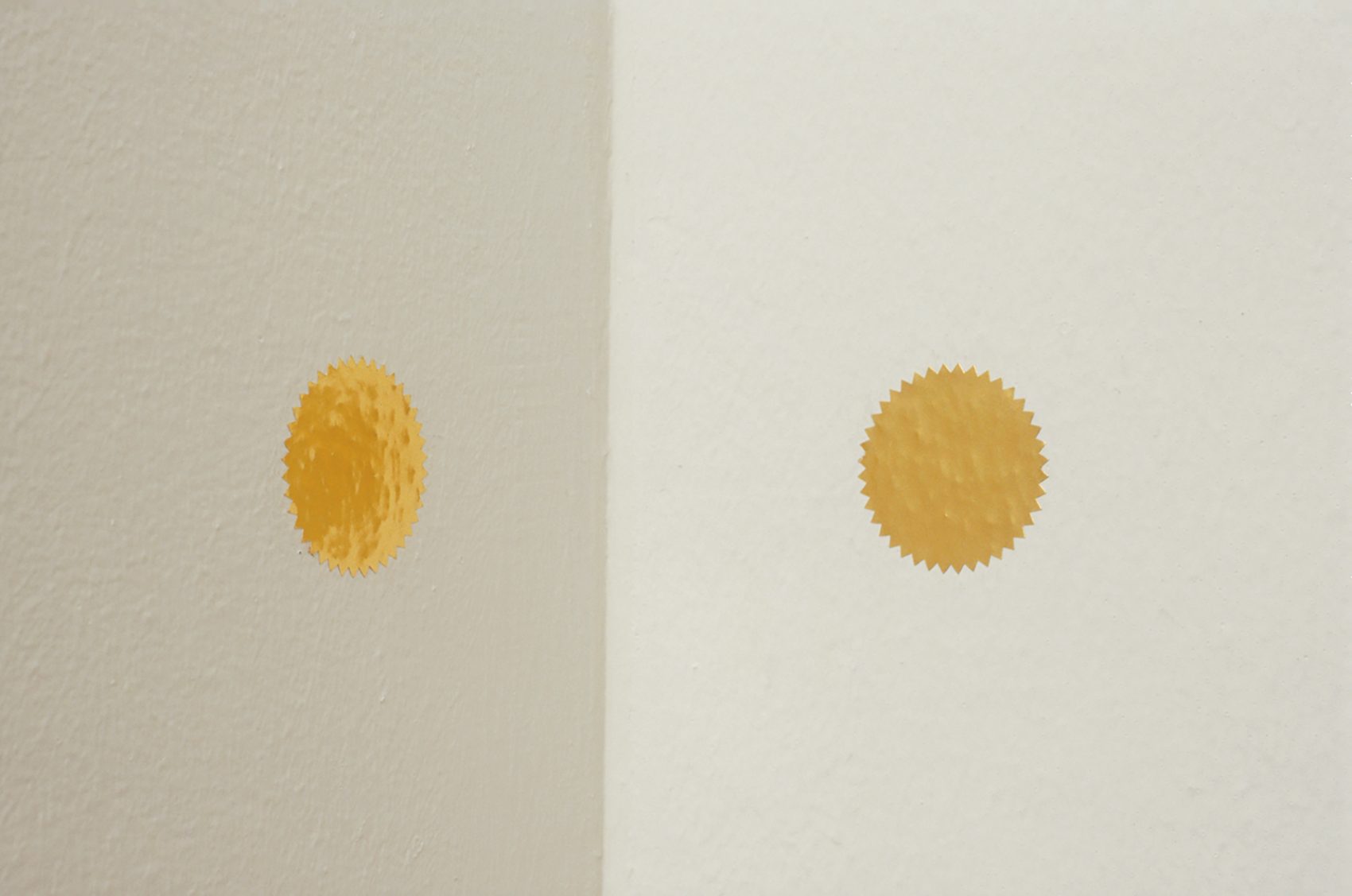

Also missing from PS1 is Becker’s Golden Force Field (1999), which might have offered a bridge between the total-installation form of Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest and the edgeless, all-encompassing field of Whole. The work, marvelously simple in design, consists of an energy field conducted via circular metallic gold seals in the corners of a room, mounted “at about shoulder height.” Becker instructs: “While you’re there, place another dot on the wall that bisects the ‘dotted’ wall. Now you should have two dots, perhaps an inch apart at 90 degrees to each other. Repeat this pattern in every main corner of the room.”29 If you want, you can take a trip to an office supply store and then install this work yourself anywhere, or imagine it in your head. In the work, Becker admits, “If I came upon this work my initial reaction would most likely be: ‘What is this shit, this scam. God, artists are getting away with murder these days . . .’ There is a good chance that viewers will think their minds are playing a trick on them.” She continues, “But this is no joke—this is real!”30 Perhaps Golden Force Field was the most “whole” thing she ever made, to be willingly held and believed in anyone’s own mind and body.

Julie Becker, A Place Called Lovely, 1999. Mixed media, 15 × 11 in. Courtesy of Greene Naftali, New York.

The life Becker lived formed the immediate and continual basis of her research as a long-term process of divining: of seeking to know the invisible. I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent seemed to avoid drawing closer connections on this, in an effort to foreground the deep conceptual strength of her work. Yet energetic forces might be more subtle than and equally powerful to conceptual ones. Entering the exhibition, it was hard not to feel deeply and in turn to identify with Becker and her work, as she clearly did with many others. Of course, this too is only another of many ways of accessing her works. In 1999, Becker made the collage A Place Called Lovely (not included in the show), in which she adapted a Time magazine cover of the computer-generated algorithm-average “New Face of America,” eerily altering it by inserting her own eyes.31 It’s strange to stare into her eyes; they hover much like the golden orbs that appear across her drawings, sculptures, and photographs. The collage speaks to the collectivity involved in her life’s work and her desire for this to continually expand, connecting with and involving the one looking, like a force field. She shows how an idea can itself be a growing ball of energy. Now that Becker is gone, her work has reached a new dimension, as if by design—a room left empty in the starkest sense, her presence everywhere. And still, as always, she makes it impossible to tell where to begin or end.

Laura Brown is a writer, editor, and curator living in New York.