Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Editorial Collective, Slide archive & library, November 2007 to present. Wooden archive box, plexiglass, submitted and collected films, videos, books, posters, slides, DVDs, and other cultural ephemera. Installation view in The Red and The Blue, curated by Jason Manley, Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA, November 2008.

In response to an art discourse in the late ‘90s that was dominated by capitulations to or reactions against the regressive rhetoric of “beauty” as professed by critics such as Dave Hickey, the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest (JOAAP) began publishing a competing discourse. Tessa Laird summed it up quite simply at the beginning of Issue 2 (published in 2003): “I don’t think Dave Hickey is Hitler, but unlike Hickey, I can’t for the life of me find beauty in places where injustice remains unchallenged.”

Since its founding in 2000, the JOAAP Editorial Collective has gone through its share of shifts and reconfigurations, as revealed by changes in the masthead over time. The collective thrives on differing opinions: “We frequently disagree on the simplest of terms (language and exchange); when disagreeing we try hard not to see conflict as a problem.”1 The editorial collective’s tolerance for disagreement has led to an extremely broad, thorough, and at times contradictory debate over politically effective art and political action. They have leveraged their collective unrest into the production of a significant run of six issues of the journal as well as a number of other publications, public events, and collective art projects. under its current guise, the JOAAP Editorial Collective is comprised of twin brothers Marc and Robby Herbst and Christina ulke. (Previous members include Cara Baldwin, Ryan Griffis, Lize Mogel, and Kimberly Varella.) On average an issue of the journal is 200 pages long and contains contributions from about 25 different writers, artists, activists, and collectives. Over time the JOAAP has printed the work of approximately 150 different contributors.

While this article will take primary interest in the contents of the first six issues of the journal, in particular points of contention and contradiction in its pages, it is important to note the variety of roles the editorial collective has taken on, including curator, archivist, art collective, event organizer, think tank, and publisher. For example, the collective has convened round table discussions on subjects such as “Emotionality of Collectivities and Social Change,” in collaboration with The Public School in May 2009.2 Their work as an art collective has taken many forms, among them performance and various direct actions. For the 2008 California Biennial at the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport Beach, the collective presented Untitled (Book Drop) (2008). During the course of the exhibition, a number of copies of the JOAAP determined by that day’s estimated Iraq war dead was dropped daily from a venting duct to the floor. The issues were then made available for free to museum visitors. In the interest of collecting and disseminating information about a variety of current social practices, the JOAAP Editorial Collective started the Slide Archive & Library, beginning in November 2007. Its contents, which were collected via open donation, include protest posters, cultural ephemera from non-object based art practices, films, books, and slides. This project, which walks the line between artwork and archive, can be accessed online and has been installed in Los Angeles at Machine Project, Lizabeth Olivera Gallery, and Occidental College. In late 2006, the JOAAP Editorial Collective curated Street Signs and Solar Ovens: Socialcraft at the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles. The Socialcraft exhibition presented a challenge to the definitions of both artistic and political activity. A wide array of objects and images flipped artist vs. activist roles, including Forkscrew Graphics’ poster iRaq (2004), with its iPod-ad-style Abu Ghraib image; Path to Freedom’s bicycle powered blender and hand-crank laundry machine that also waters your garden; and a display of preserves from the Fallen Fruit collective.

Forkscrew Graphics, iRaq poster, 2004. Exhibited in Street Signs and Solar Ovens: Solarcraft at the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles, 2006.

Up to this point the JOAAP Editorial Collective has done all of its publishing during the Bush era, and has worked over the past decade to forge “a link between radical aesthetics and political activisms” while fostering “autonomy [for] projects that build long-term infrastructures.”3 In the meantime, the JOAAP has become a viable long-term project in its own right: “As a journal, we show other peoples’ productions, we ask other groups of people ‘What needs to be said right now? What needs to be thought about right now?’”4 As the collective states in its mission statement, “We see our project… as a generous and rigorous possibility, filling the vacuum left after the de-funding of smaller institutions, the corporatization of knowledge production, and the ensuing commodification and spectacularization of discourse.”

The War on Terror and the war in Iraq, especially the February 15, 2003 protests against the U.S. invasion of Iraq, engendered one of the largest protest cultures in world history.5 Yet as their messages seemed to fall on deaf ears, some activists became disheartened. After the elections in 2000 and 2004, artists and activists were presented with the options of either going out and getting arrested in an act of civil disobedience at a direct action protest or, as Tom McKenzie puts it in JOAAP Issue 5, “accelerat[ing] themselves into alternate states of consciousness with the aid of psychoactive mushrooms,” and falling into what Mark Rodriguez calls Super-Nostalgia, inhaling the ghosts of the hippy movement and the idealization of the late ‘60s.6 There was a time when just blurting out “Donald Rumsfeld is a liar!” in a public context could act to undercut the prevailing power of propaganda. Both the simple act and its possible repercussions have been supported in the JOAAP.7 Many pages of the JOAAP are dedicated to calling for something more from artists and activists, in some places asking artists to leave the “culture bunker.” In Issue 3, John Jordan cites the action of a middle-aged woman breaking into an RAF base and causing 25 million pounds of damage to a Tornado Bomber with a hammer to advance the argument that the truly risky activist work is “[m]ore courageous and more useful than any durational performance. …More absurd, more adventurous and often more dramatic than any theatre.” He makes “a plea for the artists to abandon our identities but not our creativity; it’s a plea to value our creativity more, to understand its transformative power and apply it directly to social change.”

One objective of political action and political or critical art is creating a dialogue among artists, activists, participants, viewers, and the public at large. For artists who see themselves and their work as being inscribed within the political realm, creating conversation around an art object or political action can be an act of constituting a public, of creating a temporary public sphere. According to one school of thought represented in the journal, the hope is that as people more fully understand a political situation, they might be motivated to work for change. Interventionist art could then be considered not simply art that intervenes, but art that causes other people to intervene.8 Imagine teach-ins and installation art coming together in hybrid practice. Put another way by Jacques Rancière, “Critical art intends to raise consciousness of the mechanisms of domination in order to turn the spectator into a conscious agent in the transformation of the world.”9 However, for some contributors to the JOAAP, this is not enough. “Talk is cheap,” say Aaron Gach and Trevor Paglen. “For artists desiring to achieve material political effects, the goal of ‘creating dialogue’ or ‘raising consciousness’ frequently misses the mark.”10

The JOAAP is a vibrant document of multiple conversations, helping artists and activists alike move beyond the simplistic, persistent question: “Is it art or is it political?” In its pages, Nato Thompson, curator at Creative Time, points to a simultaneous collapse of “current art historical language” and the language of political discourse, and declares the necessity of discovering a much more exact language in both arenas.11 An identical call is made by contributor Jason Del Gandio in “Rhetoric for Radicals.” He urges readers to think more about the communicative labor of activism and to “become the radical rhetoricians that engage and alter the perceptions and languages of contemporary living.”12 These arguments encourage the cultivation of a more precise language in the aesthetic and political realms, especially where those two concerns overlap.

It shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise that the permeable border between art and politics is often in the process of being defined or dismissed in the pages of the JOAAP. In Issue 5, Mark Tribe contends, “Art rarely has a direct impact in the realm of politics. …It would be a mistake to conclude that art is politics. Art is not politics; it is politics by other means.” While this sentiment can be taken at face value, the interplay between these two worlds is obviously more complicated. Rancière’s essay “Problems and Transformations in Critical Art” examines the fairly subtle interplay between the two realms, arguing that the politics of aesthetics has opposing logics: “the logic of art that becomes life at the price of abolishing itself as art, and the logic of art that does politics on the explicit condition of not doing it at all.”13 Critical art is founded on a game of exchanges and displacements between the world of art and that of non-art; it is capable of speaking twice by consistently crossing the border in both directions. Thus Rancière’s most salient claim: “These possible politics are only ever realized in full at the price of abolishing the singularity of art, the singularity of politics, or the two together.”14

This conflation of art and politics has often come in the form of elaborate spectacle, hilarious pranks, and theatrics. This mode of working is highly contested in the pages of the JOAPP. Self-defined media activists Andrew Boyd and Stephen Duncombe of Reclaim the Streets and Billionaires for Bush argue: “Amongst the whimsical, over-the-top, crassly commercial simulated realities of Vegas lies a model of spectacle that is more populist and more participatory. …Yes, Las Vegas is fake. This is decried by sober American thinkers (‘the evisceration of reality by its simulation’) and celebrated by enthusiastic French intellectuals (‘the evisceration of reality by its simulation!!!’) but both seem to miss the point.”15 Boyd and Duncombe would argue that the spectacle, beyond eviscerating reality, could be used to happily enlist spectators into participating in the molding and shaping of the social and political realm. Elsewhere in the journal, Gach and Paglen directly contradict these strategies: “With the channels of information dissemination often so well-controlled, individuals desiring to affect change through creative action should hardly be surprised by the tactical shortcomings of ‘spectacle creation.’”16

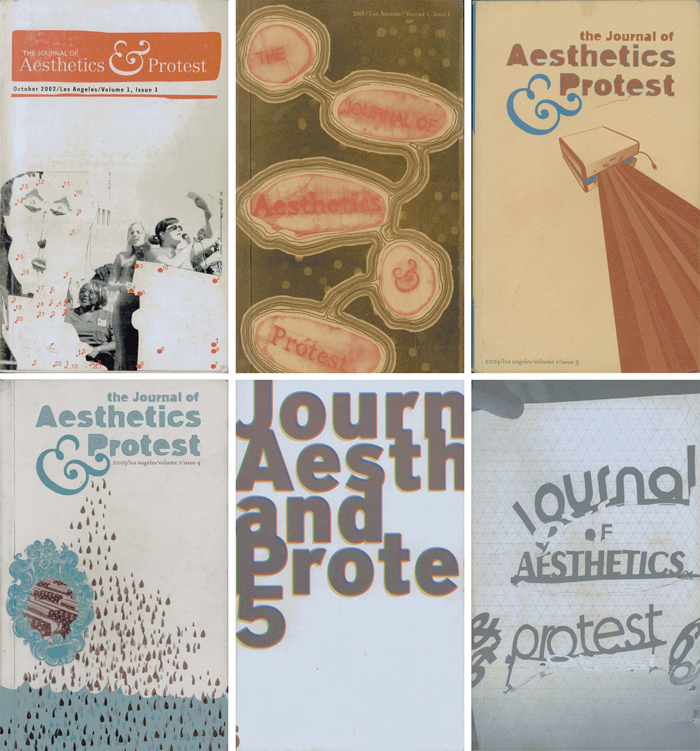

Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, Issue 1, 2002 (cover design by Marc Herbst, logo design by Ben Benjamin, Photo by y); Issue 2, 2003 (design by Kimberly Varella); Issue 3, 2004 (design by Kimberly Varella); Issue 4, 2005 (design by Kimberly Varella); Issue 5, 2007 (design by Jessica Fleischmann); and Issue 6, 2008 (design by Jessica Fleischmann).

This question of the spectacle is essentially one of whether or not to engage the mainstream using corporate media channels or the tactics of the entertainment industry. With the potentially higher impact of these tactics comes an ethical dilemma. Sarah Kanouse asks, “In insisting that successful actions must also be fun, how much have we internalized capital’s emphasis on consumption and externalized the necessity of re-forming the relations of material production? How much might we be responsible for our own co-optation?”17 Elsewhere, the pages of the JOAAP offer a differing position. Thompson asks: “What could capitalism want more than for us to burrow down and begin our supposed underground quest for new cultural products? nothing could be more complicit than our constant obsession with cultural niche markets and affinities for the supposed ‘underground.’”18

Possibly, this interest in the late conception of “the spectacle” could be more useful if thought of in the context of style, or more pertinently as a poetics of affect, as Emily Forman and Daniel Tucker suggest. “Looking at protest as something that is ‘staged,’ as opposed to natural, allows you to be strategic in how you interrogate the meaning and effectiveness of a collective action. Consider that ‘demonstrations’ are just that; …this performance is so well scripted that police agencies often ‘rehearse’ it.”19 The spectacle of protest politics, though often powerful in its own right, comes down to an economy of affect. Similarly, Robby Herbst, in conversation with Katie Grinnan in Issue 3, evokes the poetics of style in which the artist-activist brings political content in through the back door of a highly aestheticized museum practice: “Style can be just as radical as substance.”

Meditating on affect or style can be instructive, as when Paglen asks, “How can I position this project as closely to a site of instability in power as possible such that the project has real effects?”20 The urgency expressed comes from a desire to create something, whether an art object, an experience, or a political movement “and then to make it directly transformative by doing something right now,” as Robby Herbst and Brian Holmes say in Issue 4. Art movements over the history of the 20th century (at least) are mythologized as if they materialized overnight. Political movements are more realistically described as hard won over the course of a decade or two, if not longer. As Ulke says in “I Love to We,” her introduction to Issue 6: “The cultivation of collective infrastructures takes time and is unspectacular. Yet this is where resistance can find power, in the creation of permanent spaces that insert themselves into cityscapes.”

In issue 6, Robby Herbst observes: “Today it is seen as legitimate to work as an individual or a small collective, within a real or frequently improvisatory network to attempt social change—by any means necessary.”>21 A necessarily incomplete list of groups and projects mentioned in the JOAAP includes: The Bicycle Kitchen, Center for Tactical Magic, Code Pink, Craftnight, Creative Time, Critical Art Ensemble, Direct Action to Stop the War, Fallen Fruit, FOOD, Infernal Noise Brigade, Machine Project, Materials & Applications, The Pink Bloque, The Port Huron Project, Reclaim the Streets, Sundown Salon, Victory Gardens, What Cheer?, The Yes Men, and Yomango. While some of these projects are explicitly anti-war efforts, many are more modest activities that challenge a variety of infrastructures upon which the 21st century culture of war in the U.S. has been based.

The first ten years of the JOAAP were dominated by the Bush administration’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the War on Terror, and the various fictions used to garner support for such activities. In thinking back to the political activism of the Vietnam era and envisioning what might be said of more recent radical action, Robby Herbst proposed in Issue 6 that “all movements are fictions,” made up of stories told by various sources. A number of contradictory stories have been told over the past ten years. In that cacophony it’s easy to overlook radical shifts in culture, such as the obvious difference between the climate change debate today in comparison to ten years ago. The relatively recent election of Barack Obama changed some of the stories we, as a culture, tell ourselves about the current social and political climate in America. one strand that existed ten years ago and lay a conceptual foundation for the JOAAP’s very first issue, and which continues to persist today in a seemingly much more complex political environment, is the Anti- Globalization or Global Justice Movement that crystallized around the November 30, 1999, WTO meeting otherwise known as “The Battle in Seattle.” The JOAAP has chronicled a number of different arguments about and stories of the confluence of aesthetic and political movements since then. Primarily, the JOAAP has shown itself to be a long-term collective infrastructure for the exchange of information and the development of critical discourse around emerging connections between artists and activists. Their contributors and readers, both past and present, seem to recognize the necessity for such a platform, as the editorial collective looks towards their seventh issue, and continues to pull together competing narratives of how much and how little has changed over time.

Mathew Timmons has published prose, poetry and criticism. His chapbook Lip Service was recently published by Slack Buddha Press. Forthcoming are three new books: The New Poetics (Les Figues Press), a particular vocabulary, in collaboration with Marcus Civin (P S Books), and CREDIT (Blanc Press). He teaches interdisciplinary arts and writing workshops for CalArts School of Critical Studies.